In This Report

LAO CONTACTS

Prisons, Jails,

Board of State and Community Corrections

Criminal Fines and Fees,

Courts, Department of Justice

Rehabilitation Programs,

Inmate Health Care

Overall Criminal Justice

February 22, 2016

The 2016-17 Budget

Governor's Criminal Justice Proposals

Executive Summary

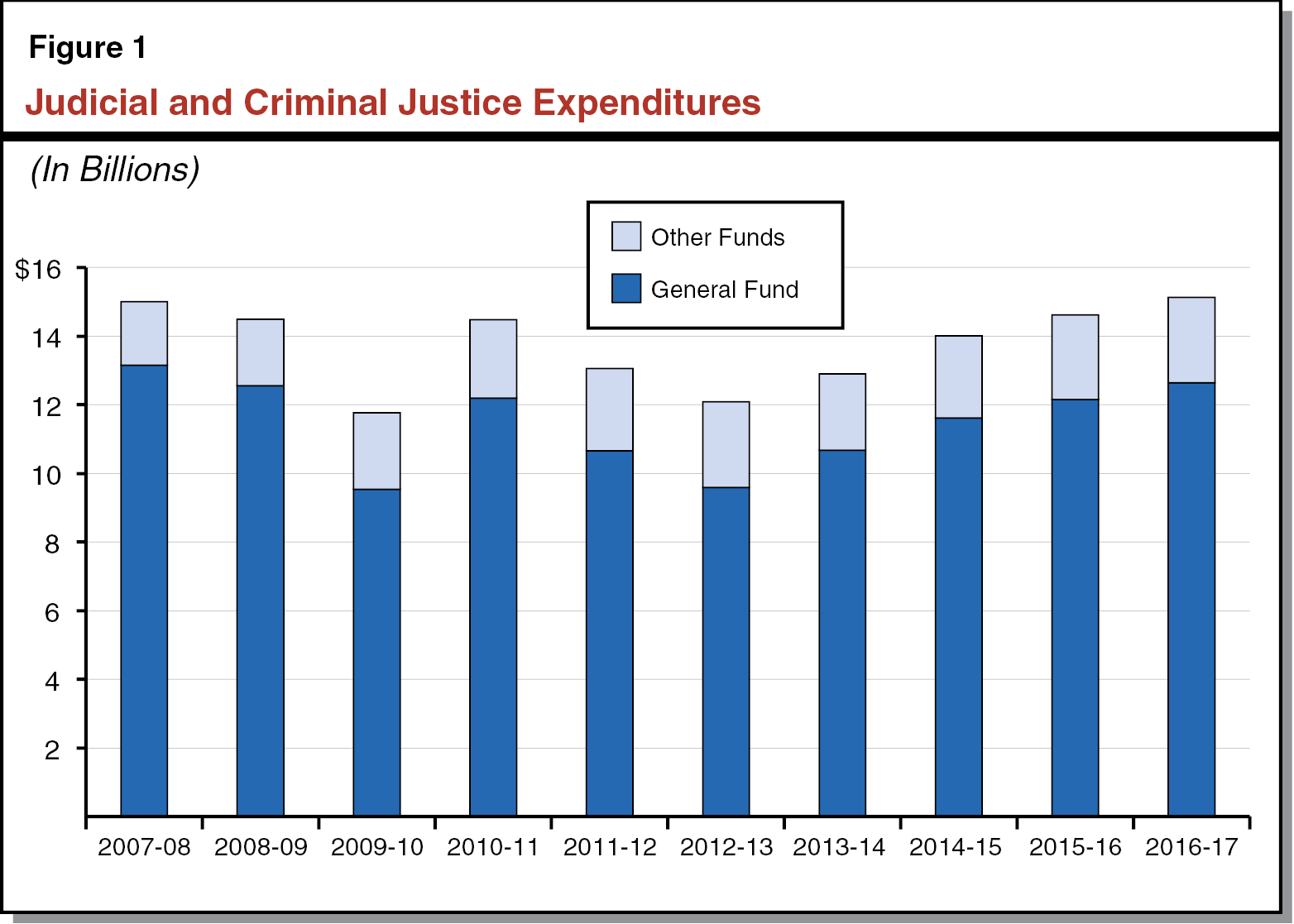

Overview. The Governor’s budget proposes a total of $15.6 billion from various fund sources for judicial and criminal justice programs in 2016–17. This is an increase of $582 million, or 3.9 percent, above estimated expenditures for the current year. The budget includes General Fund support for judicial and criminal justice programs of $12.6 billion in 2016–17, which is an increase of $571 million, or 4.7 percent, over the current–year level. In this report, we assess many of the Governor’s budget proposals in the judicial and criminal justice area and recommend various changes. Below, we summarize our major recommendations, and provide a complete listing of our recommendations at the end of the report.

Criminal Fine and Fee Revenue. The Governor’s budget includes various proposals to address operational shortfalls in several state funds due to declines in criminal fine and fee revenue. These include expenditure reductions, cost shifts to the General Fund and other funds, and cash flow loans from the General Fund. Given that the various state funds receiving fine and fee revenue have been facing financial difficulty for years, the Legislature has few options beyond approving the Governor’s proposed short–term solutions for addressing the operational shortfalls and insolvencies in these state funds in 2016–17. However, to permanently address the recurring problem, we recommend the Legislature implement ongoing, systemic changes to the state’s criminal fine and fee system. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature (1) reevaluate the overall structure of the fine and fee system, (2) increase legislative control over the use of criminal fine and fee revenue, and (3) restructure the criminal fine and fee collection process.

Plans for Complying With Court–Ordered Population Cap. In recent years, the state has been under a federal court order to reduce overcrowding in the 34 state prisons operated by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). Chapter 310 of 2013 (SB 105, Steinberg) authorized CDCR to enter into contracts to secure a sufficient amount of inmate housing to meet the court–ordered population cap and to avoid the early release of inmates which might otherwise be necessary to comply with the order. This authority is currently set to expire on December 31, 2016. The administration proposes extending the authority to December 31, 2020. The Governor’s budget includes $259 million from the General Fund to maintain about 9,000 contract beds in 2016–17. In addition, the budget assumes the continued operation of the California Rehabilitation Center (CRC) in Norco, despite the fact that the administration has indicated that closing the facility is a priority.

We recommend that the Legislature approve the administration’s requested extension of authority to procure contract beds as it is very likely that the administration will need to continue utilizing contract beds over the next several years in order to maintain compliance with the prison population cap. We also recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to close CRC because its capacity is not necessarily needed to comply with the federal court–ordered prison population cap, and its closure would result in significant ongoing General Fund savings.

Inmate Rehabilitation Proposals. The Governor’s budget includes $10.5 million to expand the availability of rehabilitation programs for long–term offenders. Research shows that rehabilitative programs are most effective when they target offenders who have been assessed as a moderate–to–high risk to reoffend. However, only a portion of the funding proposed for long–term offenders would support higher–risk offenders, even though many of these offenders are currently not receiving rehabilitative programming. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature approve only the portion of the proposal that increases rehabilitative programming opportunities for higher–risk offenders and reject the remainder of the proposal that would exclusively target long–term offenders, which tend to be of low risk.

The budget also proposes $32 million to expand the Male Community Reentry Program, which houses inmates nearing release in residential facilities and provides them with rehabilitative programming. We recommend the Legislature reject the proposal, as it is unlikely to be the most cost–effective recidivism reduction strategy given that it does not target higher–risk offenders and is very costly.

Trial Courts. The Governor’s budget proposes a $20 million General Fund base augmentation for trial court operations. The administration has not provided sufficient information to justify why the trial courts need this additional funding. For example, it is unclear what specific needs at the trial courts are not currently being met that necessitate an augmentation. Moreover, we note that the Governor’s budget already includes $72 million for workload changes, increased costs, and the expansion of specific services—making it even less clear why the proposed $20 million in resources is needed for trial court operations. Accordingly, we recommend rejecting the proposal.

County Jail Grants. The Governor’s budget proposes one–time funding of $250 million from the General Fund for jail construction. However, the administration has not provided a detailed analysis regarding the magnitude of either programming or capacity needs or the extent to which the proposed funding would meet these needs. For example, the administration has not provided an estimate of the number of additional jail beds counties need or the amount of additional rehabilitation program or health service space needed that takes into account (1) the impact of Proposition 47 or (2) the extent to which eligible counties have pursued alternatives that could reduce or eliminate the need for state funding. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal.

Criminal Justice Budget Overview

The primary goal of California’s criminal justice system is to provide public safety by deterring and preventing crime, punishing individuals who commit crime, and reintegrating criminals back into the community. The state’s major criminal justice programs include the court system, CDCR, and the Department of Justice. The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of over $15 billion for judicial and criminal justice programs. Below, we describe recent trends in state spending on criminal justice and provide an overview of the major changes in the Governor’s proposed budget for criminal justice programs in 2016–17.

State Expenditure Trends

Over the past decade, total state expenditures on criminal justice programs has varied. As shown in Figure 1, criminal justice spending declined between 2010–11 and 2012–13, primarily due to two factors. First, in 2011 the state realigned various criminal justice responsibilities to the counties, including the responsibility for certain low–level felony offenders. This realignment reduced state correctional spending. Second, the judicial branch—particularly the trial courts—received significant one–time and ongoing General Fund reductions.

Since 2012–13, overall state spending on criminal justice programs has increased. This was largely due to additional funding for CDCR and the trial courts. For example, increased CDCR expenditures resulted from (1) increases in employee compensation costs, (2) the activation of a new health care facility, and (3) costs associated with increasing capacity to reduce prison overcrowding. During this same time period, General Fund augmentations were provided to the trial courts to partially offset reductions made in prior years.

Governor’s Budget Proposals

As shown in Figure 2, the Governor’s 2016–17 budget includes a total of $15.6 billion from all fund sources for judicial and criminal justice programs. This is an increase of $582 million (3.9 percent) over the revised 2015–16 level of spending. General Fund spending is proposed to be $12.6 billion in 2016–17, which represents an increase of $571 million (4.7 percent) above the revised 2015–16 level.

Figure 2

Judicial and Criminal Justice Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Actual 2014–15 |

Estimated 2015–16 |

Proposed 2016–17 |

Change From 2015–16 |

||

|

Actual |

Percent |

||||

|

Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation |

$10,077 |

$10,395 |

$10,540 |

$145 |

1.4% |

|

General Funda |

9,804 |

10,097 |

10,273 |

176 |

1.7 |

|

Special and other funds |

273 |

299 |

267 |

–32 |

–10.6 |

|

Judicial Branch |

$3,229 |

$3,429 |

$3,604 |

$175 |

5.1% |

|

General Fund |

1,404 |

1,598 |

1,702 |

104 |

6.5 |

|

Special and other funds |

1,825 |

1,831 |

1,902 |

71 |

3.9 |

|

Department of Justice |

$724 |

$804 |

$826 |

$22 |

2.7% |

|

General Fund |

190 |

206 |

217 |

11 |

5.4 |

|

Special and other funds |

535 |

598 |

609 |

11 |

1.8 |

|

Board of State and Community Corrections |

$128 |

$185 |

$418 |

$233 |

126.3% |

|

General Fund |

68 |

68 |

329 |

261 |

384.6 |

|

Special and other funds |

59 |

117 |

89 |

–28 |

–23.9 |

|

Other Departmentsb |

$220 |

$241 |

$248 |

$7 |

2.8% |

|

General Fund |

62 |

61 |

80 |

19 |

30.7 |

|

Special and other funds |

158 |

180 |

168 |

–12 |

–6.7 |

|

Totals, All Departments |

$14,378 |

$15,054 |

$15,636 |

$582 |

3.9% |

|

General Fund |

11,528 |

12,029 |

12,601 |

571 |

4.7 |

|

Special and other funds |

2,850 |

3,025 |

3,036 |

10 |

0.3 |

|

aDoes not include revenues to General Fund to offset corrections spending from the federal State Criminal Alien Assistance Program. bIncludes Office the Inspector General, Commission on Judicial Performance, Victim Compensation and Government Claims Board, Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training, State Public Defender, funds provided for trial court security, and debt service on general obligation bonds. Note: Detail may not total due to rounding. |

|||||

Major Budget Proposals. The most significant piece of new spending included in the Governor’s budget is a proposal to provide a one–time General Fund augmentation of $250 million to the Board of State and Community Corrections (BSCC) for jail construction. The BSCC would be responsible for allocating these funds to counties. In addition, the budget includes various augmentations for CDCR and the judicial branch. For example, the Governor’s budget includes (1) $58 million to expand inmate rehabilitation programs, (2) $30 million for a new Court Innovation Grant program for trial courts, (3) $21 million for court workload associated with Proposition 47, and (4) a $20 million base augmentation for the trial courts. (Please see our recent report, The 2016–17 Budget: Fiscal Impacts of Proposition 47, for more detailed information regarding the fiscal impact of Proposition 47.)

Back to the TopCross Cutting Issue: Criminal Fine and Fee Revenue

LAO Bottom Line. Given that various state funds receiving criminal fine and fee revenue have been facing financial difficulty for years, the Legislature has few options beyond approving the Governor’s proposed short–term solutions for addressing the operational shortfalls and insolvency in these state funds in 2016–17. However, to permanently address the recurring problem, we recommend the Legislature implement ongoing, systemic changes to the state’s criminal fine and fee system. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature (1) reevaluate the overall structure of the fine and fee system, (2) increase legislative control over the use of criminal fine and fee revenue, and (3) restructure the criminal fine and fee collection process.

Background

Collection of Criminal Fines and Fees. Upon conviction of a criminal offense (including traffic violations), individuals are typically required by the court to pay various fines and fees as part of their punishment. The total amount owed by an individual consists of a base fine specified in statute for each criminal offense, as well as various additional charges (such as other fines, fees, forfeitures, penalty surcharges, assessments, and restitution orders). Collection programs—operated by both courts and counties—collect payments from individuals and then distribute them to numerous funds to support various state and local government programs and services. State law dictates a very complex process for the distribution of fine and fee revenue. The complexity arises from the numerous statutes that specify (1) the order in which the payments collected from an individual are to be used to satisfy the various fines and fees and (2) how the revenue from each of the individual fines and fees will be distributed among various state and local funds.

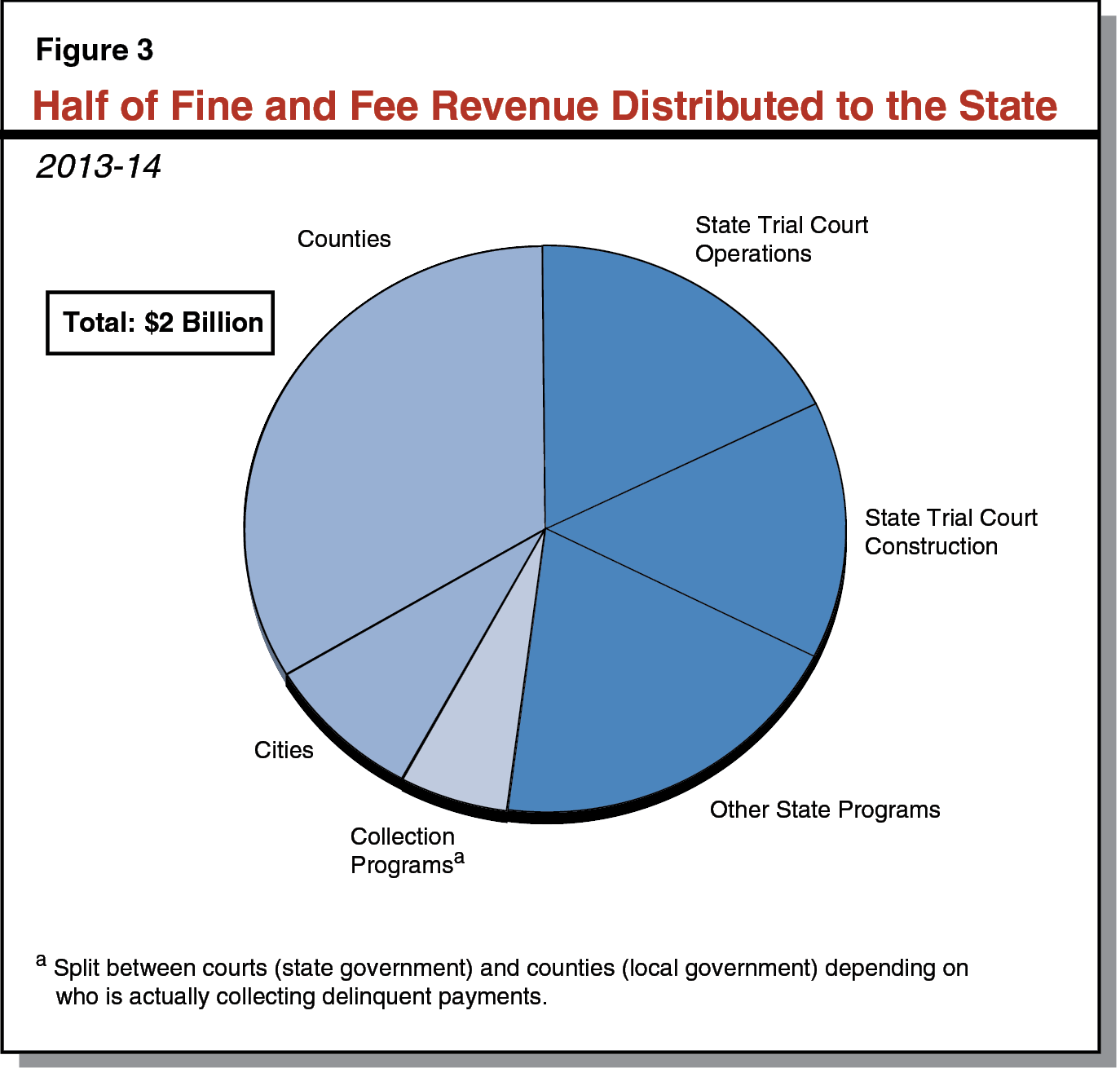

Use of Criminal Fine and Fee Revenue. In 2013–14, the total amount of criminal fine and fee revenue distributed to state and local governments totaled nearly $2 billion. As shown in Figure 3, the state received a little over $1 billion (or roughly half) of this revenue. Of this amount, a little less than two–thirds went to support trial court operations and construction. The remainder supported various other state programs, such as victim–witness assistance, peace officer training, and the state’s DNA laboratory. Additionally, in accordance with state law, collection programs received $114 million (or 6 percent) for certain operational costs related to the collection of delinquent payments. Finally, local governments received the remaining $820 million (or 42 percent) in distributed revenue. Of this amount, $657 million (or 80 percent) went to the counties.

Funds Facing Persistent Operational Shortfalls From Declines in Fine and Fee Revenue. According to available data, the total amount of fine and fee revenue distributed to state and local governments has declined since 2010–11. As a result, a number of state funds receiving such revenue have been in operational shortfall for years—meaning annual expenditures exceed annual revenues—and some have become insolvent. Figure 4 lists the 11 state funds facing shortfalls, including 6 that are currently insolvent. As shown in the figure, the state has adopted a number of short–term solutions in recent years to help address the shortfalls facing some of these funds. These actions include: (1) requiring programs to make expenditure reductions, (2) generating more revenue, and (3) shifting costs to the General Fund or other state funds.

Figure 4

Summary of State Funds Facing Shortfalls Related to Declines in Criminal Fine and Fee Revenue

|

Fund |

Short–Term Solutions Proposed or Adopted |

|||

|

Reduce Expenditures |

Increase Revenues |

Shift Costs to General Fund |

Shift Costs to Other Funds |

|

|

Currently Insolvent |

||||

|

Corrections Training Fund |

x |

x |

— |

x |

|

Improvement and Modernization Funda |

x |

— |

x |

— |

|

Peace Officers Training Fund |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Traumatic Brain Injury Fund |

— |

— |

— |

x |

|

Trial Court Trust Funda |

— |

— |

x |

— |

|

Victim–Witness Assistance Fund |

— |

— |

— |

x |

|

Facing Immediate Insolvency |

||||

|

DNA Identification Fund |

x |

x |

x |

— |

|

Driver Training Penalty Assessment Fund |

x |

— |

— |

— |

|

Potentially Insolvent in Future |

||||

|

Immediate and Critical Needs Accounta |

x |

— |

— |

— |

|

Restitution Fund |

x |

— |

— |

— |

|

State Court Facilities Construction Funda |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

aJudicial branch special fund. |

||||

For example, the Legislature enacted an 18–month traffic amnesty program last year to increase revenues to address the insolvency of two funds—the Peace Officers Training Fund (POTF) and the Corrections Training Fund (CTF). The amnesty program reduces the debt owed for qualifying traffic offenses if individuals pay the reduced amount in full or enroll in a payment plan. All revenues from the program are to be distributed in accordance with state law except for the portion deposited into the State Penalty Fund (SPF). Instead of distributing revenues from the SPF to nine state funds as required under state law, all revenues from the amnesty program will instead be distributed only to the POTF and CTF.

Governor’s Proposals

The Governor’s budget includes various proposals to address operational shortfalls from declines in criminal fine and fee revenue. The Governor’s proposals address all of the funds that are listed as currently insolvent or facing immediate insolvency in Figure 4. (As discussed below, the budget does not address those funds that could potentially become insolvent in the future.) Specifically, the administration proposes the following actions:

- Expenditure Reductions. The Governor’s budget proposes reducing expenditures from CTF by $490,000 and from the DNA Identification Fund by $6 million. The budget proposes provisional language to allow the Department of Finance to increase expenditures from the DNA Identification Fund to the extent more revenues are deposited into the fund than currently estimated. Additionally, due to a decline in revenue to the Driver Training Penalty Assessment Fund, the Governor’s budget proposes to reduce the amount transferred from the fund to POTF by $3 million.

- Cost Shifts. The Governor’s budget proposes to shift nearly $31 million in costs from various funds that receive fine and fee revenue to the General Fund. Specifically, the budget proposes to shift costs of $13 million from POTF, $9 million from the Trial Court Trust Fund, and $9 million from the Improvement and Modernization Fund (IMF). The budget also shifts about $4 million in costs from the Victim–Witness Assistance Fund and $360,000 in costs from the Traumatic Brain Injury Fund to other special funds.

- Cash Flow Loans. The Governor’s budget proposes budget bill language to authorize short–term cash flow loans from the General Fund to POTF and CTF related to the 18–month amnesty program enacted last year. These loans are intended to be used to cover revenue shortfalls in the event that there is a delay in the receipt of revenues from the amnesty program. However, if amnesty revenues come in below expectations, these loans could effectively shift additional costs to the General Fund.

LAO Assessment

The Governor’s budget takes positive steps towards preventing funds from becoming insolvent due to the decline in criminal fine and fee revenue. However, the budget only includes short–term solutions to address a continuing problem. Without broader changes to the overall fine and fee system, the state will likely need to repeatedly identify and implement short–term solutions in future years.

Governor’s Proposals Provide Only Short–Term, Partial Solutions

The Governor’s budget only provides short–term solutions to address the ongoing problem of declining fine and fee revenue. For example, the budget proposes shifting nearly $31 million in costs from various funds to the General Fund—which does not address their ongoing solvency. Moreover, the Governor’s proposals only help address some of the state funds that are facing shortfalls or insolvency. The budget does not have proposals for other funds that will be facing shortfalls or insolvency in the future. For example, according to judicial branch estimates, absent any expenditure reductions, the State Court Facilities Construction Fund is estimated to become insolvent in 2022–23 with a projected deficit of $29.5 million. This deficit would continue to grow and would reach $540 million by the end of the judicial branch’s forecast period in 2037–38.

Improvements Needed to Overall Fine and Fee System

The key shortcoming of the Governor’s proposals is that they fail to address the structural problems with the fine and fee system. These issues are described in two reports on the fine and fee system that we have released over the past couple of years.

In our January 2016 report, Improving California’s Criminal Fine and Fee System, we identified four major problems with how fines and fees are assessed and distributed. First, we found that the existing system distributes fine and fee revenue based on various statutory formulas, making it difficult for the Legislature to control how such revenue is used. This is because the current formula–based system limits the information available to guide legislative decisions, makes it difficult for the Legislature to reprioritize the use of such revenue, and allows administering entities to maintain significant control over the use of funds. Second, the existing system distributes revenue in a manner that is not generally based on program need—thereby resulting in programs receiving more or less funding than needed. Third, the complexity of the existing system makes it difficult for collection programs to accurately distribute fine and fee revenue. Finally, a lack of complete and accurate data on fine and fee collections and distributions makes it difficult for the Legislature to conduct fiscal oversight.

Additionally, in our November 2014 report, Restructuring the Court–Ordered Debt Collection Process, we identified a number of weaknesses in the fine and fee collection process. These weaknesses included a lack of clear fiscal incentives for programs to collect debt in a cost–effective manner or to maximize the total amount of debt they collect as well as a lack of complete, consistent, and accurate reporting on how programs collect debt to allow for comprehensive evaluations of program performance.

LAO Recommendations

The Governor’s proposed short–term solutions address the operational shortfalls and fund insolvency in the near–term. Given that these funds have been facing financial difficulty for years, the Legislature has few options beyond approving the Governor’s proposals. However, the proposed budget fails to provide longer–lasting solutions. For example, the administration’s approach to addressing the POTF insolvency has forced the Legislature to identify and implement short–term solutions for the fund annually since 2014–15. Thus, we recommend the Legislature focus on addressing the systemic problems with the state’s criminal fine and fee system we identified above by taking a number of actions to improve the overall system.

Improve Overall Fine and Fee System. To address the systemic problems with the state’s criminal fine and fee system, we recommend that the Legislature improve the state’s process for assessing and distributing criminal fine and fee revenue, as outlined in our January 2016 report. Specifically, we recommend:

- Reevaluating Overall Structure of System. First, we recommend that the Legislature reevaluate the overall structure of the fine and fee system to ensure the system is consistent with its goals. As part of this process, the Legislature will want to determine the specific goals of the system, whether ability to pay should be incorporated into the system, what should be the consequences for failing to pay, and whether fines and fees should be regularly adjusted.

- Increase Legislative Control Over Fine and Fee Revenue. Second, we recommend the Legislature increase its control over the use of criminal fine and fee revenue to ensure that its uses are in line with legislative priorities by (1) requiring that most criminal fine and fee revenue be deposited in the state General Fund, (2) consolidating most fines and fees into a single, statewide charge, (3) evaluating the existing programs supported by fine and fee revenues, and (4) mitigating the impacts of potential changes to the fine and fee system on local governments.

To complement these recommended changes to the assessment and distribution of criminal fine and fee revenue, we also recommend that the Legislature restructure the criminal fine and fee collection process by implementing the recommendations outlined in our November 2014 report. In particular, we recommend (1) implementing a pilot program that would provide collection programs with an incentive to maximize the amount of debt they collect in a cost–effective manner and (2) improving data collection and measurements of performance. Such a restructuring would maximize the amount of revenue available for deposit into the General Fund. This would help mitigate any potential impacts from continued or further declines in fine and fee revenue.

Improving System Would Eliminate Need to Repeatedly Identify Short–Term Funding Solutions. Our recommendations for improving the overall structure of the fine and fee system focuses on structural, ongoing changes that eliminate the need to repeatedly identify short–term solutions to address shortfalls and insolvency in funds supported by fines and fees. Instead, the Legislature would provide those programs it believes are statewide priorities with the funding level it believes is necessary to deliver services at a desired level, irrespective of fluctuations in fine and fee revenue. We provide two examples below.

- IMF. As discussed above, the Governor proposes shifting about $9 million in costs from the IMF to the General Fund in order to help the IMF remain solvent. Specifically, these are costs related to the Phoenix project, which is the judicial branch’s statewide financial system. Under our recommended changes, the IMF would no longer receive fine and fee revenue based on existing statutory formulas. Instead, these revenues would be deposited in the General Fund. In addition, the Legislature would review the programs currently supported by the IMF to determine whether they merit support relative to other General Fund priorities. Those that are determined to be a priority would receive whatever level of General Fund support the Legislature determined was appropriate. For programs that the Legislature does not feel are a priority for support, it could either (1) eliminate the program or (2) seek alternative fund sources. For example, it could require the trial courts to pay for the Phoenix project from the Trial Court Trust Fund.

- POTF and CTF. Currently, the Commission on Peace Officers Standards and Training (POST) and the Standards and Training for Local Corrections Program in BSCC receive funding from POTF and CTF respectively. Under our approach, POST and BSCC would no longer be supported by fine and fee revenue. Instead, the Legislature would first determine whether these programs merit General Fund support. To the extent the Legislature decided to fund these programs, it would then direct POST and BSCC to provide it with information to help assess how much General Fund support is appropriate. For example, the Legislature could direct both programs and their stakeholders (such as local law enforcement) to report on options for reducing local law enforcement training costs, such as by identifying unnecessary or low–priority training for potential elimination.

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

Overview

The CDCR is responsible for the incarceration of adult felons, including the provision of training, education, and health care services. As of February 3, 2016, CDCR housed about 127,000 adult inmates in the state’s prison system. Most of these inmates are housed in the state’s 35 prisons and 43 conservation camps. About 9,000 inmates are housed in either in–state or out–of–state contracted prisons. The department also supervises and treats about 44,000 adult parolees and is responsible for the apprehension of those parolees who commit new offenses or parole violations. In addition, about 700 juvenile offenders are housed in facilities operated by CDCR’s Division of Juvenile Justice, which includes three facilities and one conservation camp.

The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $10.5 billion ($10.3 billion General Fund) for CDCR operations in 2016–17. Figure 5 shows the total operating expenditures estimated in the Governor’s budget for the current year and proposed for the budget year. As the figure indicates, the proposed spending level is an increase of $145 million, or about 1 percent, from the revised 2015–16 spending level. This increase reflects higher costs related to (1) various proposals to expand rehabilitation programs (2) debt–service payments on lease revenue bonds issued for prison construction, and (3) inmate population–related adjustments. This additional spending is partially offset by (1) reduced spending for contract beds, (2) savings from the conversion of segregated housing units to general population housing units, and (3) reductions in the parolee population.

Figure 5

Total Expenditures for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2014–15 Actual |

2015–16 Estimated |

2016–17 Proposed |

Change From 2015–16 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Prisons |

$8,956 |

$9,138 |

$9,278 |

$140 |

2% |

|

Adult parole |

450 |

554 |

554 |

— |

— |

|

Administration |

461 |

473 |

473 |

— |

— |

|

Juvenile institutions |

173 |

186 |

188 |

2 |

1 |

|

Board of Parole Hearings |

37 |

44 |

48 |

4 |

10 |

|

Totals |

$10,077 |

$10,395 |

$10,540 |

$145 |

1% |

Adult Prison Population Projected to Increase Slightly and Parolee Population Projected to Decline

LAO Bottom Line. We withhold recommendation on the administration’s adult population funding request until the May Revision. However, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to provide it with estimates of savings from the delayed activation of the infill facility at R.J. Donovan prison no later than the April 1 so that these adjustments can be incorporated into the department’s budget.

Background

The average daily prison population is projected to be about 128,800 inmates in 2016–17, an increase of about 1,200 inmates (1 percent) from the estimated current–year level. This increase is primarily due to the fact that CDCR is projecting a slight increase in the number of inmates sentenced to prison by the courts. The average daily parole population is projected to be about 42,600 in 2016–17, a decrease of about 1,400 parolees (3 percent) from the estimated current–year level. This decrease is due to a decline in the number of individuals being paroled after being resentenced under Proposition 47.

Governor’s Proposal

As part of the Governor’s January budget proposal each year, the administration requests modifications to CDCR’s budget based on projected changes in the prison and parole populations in the current and budget years. The administration then adjusts these requests each spring as part of the May Revision based on updated projections of these populations. The adjustments are made both on the overall population of offenders and various subpopulations (such as inmates housed in contract facilities and sex offenders on parole).

As can be seen in Figure 6, the administration proposes a net decrease of $700,000 in the current year and a net increase of $14.1 million in the budget year. The current–year net decrease in costs is primarily due to a projected decline in the department’s utilization of contract beds. These savings are mostly offset by costs related to a projected increase in the number of inmates in state operated prisons. The budget–year net increase in costs is largely related to (1) adjustments to health care staff and (2) a projected increase in the number of inmates in state operated prisons. These increases are partly offset by a projected reduction in the utilization of contract beds.

Figure 6

Governor’s Population–Related Proposals

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

|

|

Population Assumptions |

||

|

Prison Population—2015–16 Budget Act |

129,581 |

129,581 |

|

Prison Population—Governor’s 2016–17 budget |

127,681 |

128,834 |

|

Prison Population Adjustments |

–1,900 |

–747 |

|

Parole Population—2015–16 Budget Act |

45,047 |

45,047 |

|

Parole Population—Governor’s 2016–17 budget |

43,960 |

42,571 |

|

Parole Population Adjustments |

–1,087 |

–2,476 |

|

Budget Adjustments |

||

|

Health care staffing |

$1.0 |

$25.6 |

|

Inmate related |

2.2 |

15.5 |

|

Contract bed |

–3.4 |

–27.1 |

|

Other |

–0.5 |

0.1 |

|

Proposed Budget Adjustments |

–$0.7 |

$14.1 |

Adjustments Do Not Reflect Delayed Infill Activation

The 2015–16 Budget Act included $14.6 million for the activation of a new infill facility at R.J. Donovan prison in San Diego based on an assumption that the facility would be opened in February 2016. The department indicates that due to construction delays the activation will now occur in May 2016. This should reduce workload for CDCR in 2015–16 as the department will need the correctional officers that will be assigned to the prison for three fewer months than previously assumed. However, the administration’s requested budget for CDCR does not reflect any savings from such workload reductions. We note that the department informs us that it has placed a freeze on hiring custody staff for the facility and that it is currently developing an estimate of the resulting savings.

LAO Recommendation

We withhold recommendation on the administration’s adult population funding request until the May Revision. We will continue to monitor CDCR’s populations and make recommendations based on the administration’s revised population projections and budget adjustments included in the May Revision. However, we recommend that the Legislature direct the department to provide it with estimates of savings from the delayed activation of the infill facility at R.J. Donovan prison no later than the April 1 so that these adjustments can be incorporated into the department’s budget.

Plans for Complying With Court–Ordered Population Cap

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend that the Legislature approve the administration’s requested extension of authority to procure contract beds as it is very likely that the administration will need to continue utilizing contract beds over the next several years in order to maintain compliance with the prison population cap. We also recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to close the California Rehabilitation Center (CRC) in Norco because its capacity is not necessarily needed to comply with the federal court–ordered prison population cap and its closure would result in significant ongoing General Fund savings.

Background

Federal Court Orders Prison Population Cap. In recent years, the state has been under a federal court order to reduce overcrowding in the 34 state prisons operated by CDCR. Specifically, the court found that prison overcrowding was the primary reason the state was unable to provide inmates with constitutionally adequate health care and ordered the state to reduce its prison population to 137.5 percent of design capacity by February 28, 2016. (Design capacity generally refers to the number of beds CDCR would operate if it housed only one inmate per cell and did not use temporary beds, such as housing inmates in gyms. Inmates housed in contract facilities or fire camps are not counted toward the overcrowding limit. For more information regarding the federal court–ordered population cap, please see our report, The 2014–15 Budget: Administration’s Response to Prison Overcrowding Order.)

CDCR Has Maintained Buffer to Avoid Exceeding Population Cap. The court also appointed a compliance officer. If the prison population exceeds the population cap at any point in time, the compliance officer is authorized to order the release of the number of inmates required to meet the cap. In order to ensure that such releases do not occur if the prison population increases unexpectedly, CDCR has intentionally reduced the prison population below the court–required cap by thousands of inmates. This gap between the number of inmates CDCR is allowed to house in its 34 prisons and the number it actually houses acts as a “buffer” against the population cap.

Prison Population Currently Below Cap. As of January 2016, the inmate population in the state’s prisons was about 900 inmates below the February 2016 cap. However, this buffer is expected to grow substantially with the activation of three new infill facilities that will add about 2,400 beds in the spring of 2016, capable of holding 3,300 inmates if crowded to 137.5 percent of design capacity. The court has not yet determined how it will count this new capacity towards calculating the prison population cap. For example, it is not clear whether the court would consider the new cap to be 3,300 inmates higher as soon as these facilities are activated, or if it would not do so until these facilities are actually filled with inmates. However, we assume the court will count these beds in the same way it has counted additional capacity from the activation of the California Health Care Facility in Stockton. Accordingly, we assume these 2,400 beds would allow CDCR to house an additional 3,300 inmates in the state’s 34 prisons as soon as they are activated. As we discuss below, the Governor’s budget projects that the state will maintain compliance with the court–ordered population cap throughout 2016–17.

Administration’s Plan to Comply With Prison Population Cap

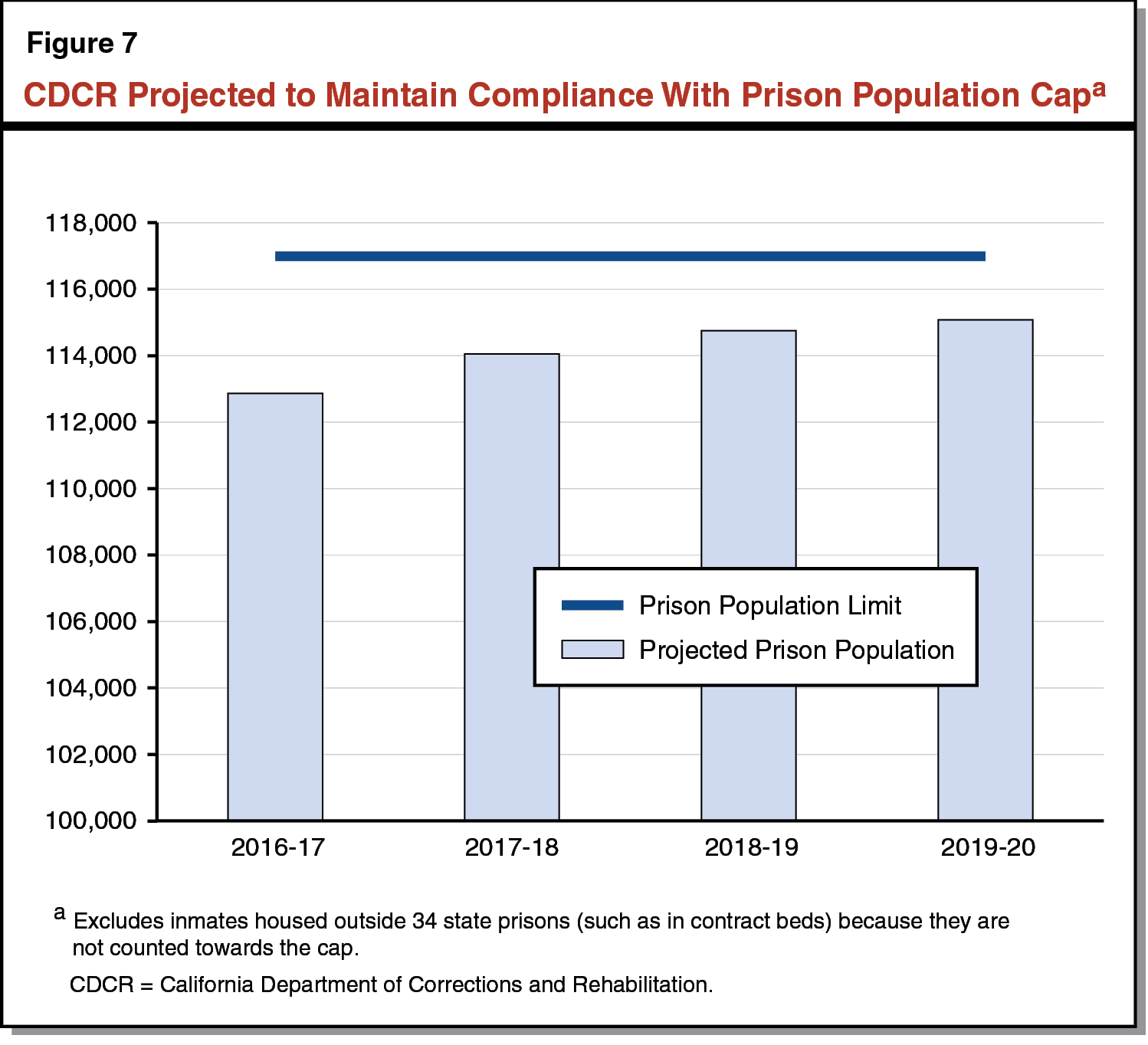

The Governor’s proposed budget for CDCR assumes a total inmate population of about 128,800 in 2016–17 and proposes to house about 112,900 of these inmates in the state’s 34 prisons and about 15,900 of these inmates outside of the 34 prisons (such as in contract facilities and fire camps). Given the design capacity of the 34 prisons, the department could house up to 117,000 inmates in state prisons under the court order. Accordingly, the Governor’s proposed budget for CDCR would provide sufficient prison capacity to maintain an average buffer of about 4,100 inmates in 2016–17. The administration’s plan relies on two key proposals to achieve a buffer of this size: (1) the utilization of contract prison beds and (2) the continued operation of CRC. These proposals are described below.

Proposed Extension of Authority to Procure Contract Bed Capacity. Chapter 310 of 2013 (SB 105, Steinberg) authorized CDCR to enter into contracts to secure a sufficient amount of inmate housing to meet the court–ordered population cap and to avoid the early release of inmates which might otherwise be necessary to comply with the order. This authority is currently set to expire on December 31, 2016. The administration proposes extending the authority to December 31, 2020. The Governor’s budget includes $259 million from the General Fund to maintain about 9,000 contract beds in 2016–17. (This does not include about 2,400 beds at California City prison which is leased from a private provider but staffed and operated by CDCR.) This represents a decrease of about 8 percent from the revised current–year funding level of $283 million for about 10,000 contract beds. As mentioned above, inmates housed in contract beds are not counted towards the population cap.

Budget Assumes Continuing Operation of CRC. The administration’s plan for reorganizing CDCR following the 2011 realignment of adult offenders called for the closure of CRC by 2015, due to its age and deteriorating infrastructure. However, Chapter 310 authorized the continued operation of CRC because it was determined that the capacity would be needed to comply with the population cap. The prison has a design capacity of about 2,500 (allowing the state to house 3,400 inmates at the overcrowding limit of 137.5 percent) and currently houses about 2,900 inmates. As part of the 2015–16 Budget Act, the Legislature required the administration to provide an updated comprehensive plan for the state prison system, including a permanent solution to the decaying infrastructure at CRC. The administration’s plan states that closing CRC is a priority but that the capacity will be needed for the next few years in order to maintain compliance with the prison population cap. The Governor’s budget includes $6 million for special repairs at CRC to address some of the prison’s most critical infrastructure needs (such as improvements to electrical and plumbing systems).

LAO Assessment

Our analysis indicates that the administration’s plan would likely maintain compliance with the prison population cap for the next several years. However, we find that the plan (1) provides more prison capacity than necessary and (2) does not provide a permanent solution for the decaying infrastructure at CRC, as required by the Legislature.

Plan Would Likely Result in Ongoing Compliance With Population Cap. As shown in Figure 7, the administration’s plan would maintain compliance through 2019–20 under CDCR’s current population projections. This assumes that the department maintains the same level of contract bed capacity in future years as in 2016–17.

Administration Has Not Provided Permanent Plan for CRC. In our view, a permanent solution for CRC would require either (1) a timeline for closing the institution or (2) a comprehensive list of the major infrastructure deficiencies at the prison, a timeline for completing the projects needed to remedy such deficiencies to keep the prison open, and the estimated cost of doing so. The administration has provided neither. Moreover, the administration’s proposal for special repair funding for CRC appears to be wholly insufficient to meet the needs of the institution. The amount of funding needed to fully address infrastructure needs at CRC is unknown but we estimate that it could be a couple hundred million dollars. Assuming lease revenue bonds are used to finance these costs, we estimate the state would incur around $15 million annually in debt–service payments. As such, the $6 million proposed by the administration for special repairs at CRC is only a small fraction of the true need and represents little more than a partial, temporary solution to the problem.

Administration’s Plan Would Result in Excessive, Costly Buffer. As discussed above, the administration’s proposed budget for CDCR in 2016–17 would maintain an average buffer of about 4,100 inmates in 2016–17. We acknowledge that some buffer is needed to avoid violating the court order if the inmate population increases unexpectedly. However, based on our analysis of historical population fluctuations, we find that the administration could maintain a much smaller buffer—about 2,250 inmates—without substantially increasing the risk of violating the prison population cap. We note that CDCR has previously indicated that it believes a buffer in the range of 2,000 to 2,500 would be an appropriate ongoing level.

Accordingly, it appears that CDCR could reduce its prison capacity in 2016–17 by almost a couple thousand beds. It could do so by either (1) reducing its utilization of contract beds or (2) reducing capacity within its 34 prisons, such as by closing housing units or an entire prison. Maintaining the buffer at the level proposed by the administration would come at a significant cost relative to alternative approaches. This is because the department saves about $18,000 annually by taking an inmate out of a contract bed and placing the inmate in one of the state’s prisons. Alternatively, the state could achieve even greater savings—as much as $59,000 annually per inmate—by consolidating these inmate reductions and closing an entire state prison.

LAO Recommendation

Approve Extension of Contract Bed Authority. We recommend that the Legislature approve the administration’s requested extension of authority to procure contract beds. It is very likely that the administration will need to continue utilizing contract beds over the next several years in order to maintain compliance with the prison population cap.

Reduce Prison Capacity by Closing CRC. We recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to reduce its prison capacity in order to achieve a reduced buffer of 2,250 in 2016–17. We further recommend that the Legislature direct the department to achieve this capacity reduction by closing CRC. As shown in Figure 8, we estimate this approach would eventually achieve net savings of roughly $131 million annually relative to the Governor’s proposed approach. These savings are achieved primarily from reduced costs to operate CRC but also include reduced debt service from avoided capital outlay costs that we estimate would need to be invested in order to keep CRC open permanently. These savings would be somewhat offset by increased costs for contract beds needed to replace a portion of the capacity lost from the closure of CRC. We also recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposed augmentation of $6 million for special repairs at CRC as these repairs would be unnecessary if CRC is closed.

Figure 8

Closing CRC Would Save $131 Million Relative to Governor’s Approach

2017–18 Fiscal Year (Dollars in Millions)

|

Governor’s Approach |

LAO Recommendation |

|

|

Status of CRC |

Open |

Closed |

|

Contract beds |

10,300 |

11,852 |

|

Surplus prison capacity (or “buffer”)a |

4,123 |

2,250 |

|

Annual Savings Relative to Governor’s Plan |

— |

$131 |

|

aAssumes administration maintains 2016–17 buffer. CRC = California Rehabilitation Center. |

||

We note that it would likely take at least a year before CRC could be closed. As such, the above savings would likely not be realized until at least 2017–18. In addition, it is possible that closing CRC could actually increase costs somewhat during the period when CRC is being closed. This is because the department may need to replace some of the lost capacity from closing CRC by increasing its use of contract beds. The precise fiscal effect of closing CRC in the short term is unknown and would depend primarily on (1) how the court adjusts the prison population cap during the time that CRC is being shut down and (2) how quickly the department is able to achieve operational savings at CRC as it reduces the prison’s population. At most, we estimate that closing CRC could result in increased costs in the low tens of millions of dollars in 2016–17. In the long term, CDCR would likely need to procure additional contract beds because it is projecting that the inmate population will increase by a couple thousand by 2019–20. We also note that to the extent the Legislature prioritizes reducing contract beds over closing CRC, it could still achieve a portion of the above savings—about $33 million in 2016–17 relative to the Governor’s approach—by directing the department to reduce its buffer to 2,250 inmates by reducing its use of contract beds.

Drug Interdiction

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend that the Legislature, approve the extension of random drug testing for one additional year because the program has allowed CDCR to identify more inmates using illegal drugs, but reject the remainder of the Governor’s proposal to extend the pilot drug interdiction program due to the lack of conclusive evidence at this time regarding program effectiveness.

Background

Two–Year Pilot Program Initiated in 2014–15. The Legislature provided CDCR with $5.2 million (General Fund) in both 2014–15 and 2015–16 to implement a two–year pilot program intended to reduce the amount of drugs and contraband in state prisons. Of this amount, $750,000 annually was used for random drug testing of 10 percent of inmates per month at all 34 state prisons and the California City prison, which are all operated by CDCR. (We note that CDCR had redirected resources in 2013–14 to begin random drug testing 10 percent of the inmate population each month beginning January 2014. As such, the department had already established a baseline of drug usage prior to the start of the pilot.) The remaining amount was used to implement enhanced interdiction strategies at 11 institutions, with 8 prisons receiving a “moderate” level of interdiction and 3 prisons receiving an “intensive” level. According to CDCR, each of the moderate institutions received the following: (1) at least two (and in some cases three) canine drug detection teams; (2) two ion scanners to detect drugs possessed by inmates, staff, or visitors; (3) X–ray machines for scanning inmate mail, packages, and property as well as the property of staff and visitors entering the prison; and (4) one drug interdiction officer. In addition to the above resources, each of the intensive institutions received: (1) one additional canine team, (2) one additional ion scanner, (3) one full body scanner at each entrance and one full body X–ray scanner for inmates, and (4) video cameras to surveil inmate visiting rooms. In 2015, the Legislature passed legislation requiring the department to evaluate the pilot drug testing and interdiction program within two years of its implementation.

Governor’s Proposal

Increased Funding to Extend and Expand Pilot Program. The Governor’s budget for 2016–17 requests $7.9 million in one–time funding from the General Fund and 51 positions to extend the enhanced drug interdiction pilot program for an additional year, as well as expand the level of services provided through the pilot program. According to CDCR, the continuation of the existing pilot program for one more year would allow the department to collect additional data to analyze its effectiveness. In addition, CDCR intends to expand certain interdiction efforts to (1) increase the frequency of random screening of staff and visitors at intensive interdiction prisons and (2) lease three additional full body X–ray machines to screen visitors. The department states that these additional resources are necessary to assess the efficacy of increased screening.

The department has indicated that it intends to issue a preliminary evaluation report on the pilot program but has not provided an estimate of when that report will be released. In addition, the department intends to issue a final evaluation report in the spring of 2017.

LAO Assessment

Interdiction Efforts Do Not Appear to Be Effective. According to CDCR, the goals of its drug interdiction efforts are to (1) reduce inmate drug use and (2) increase institutional security in various ways, such as by reducing inmate violence and lockdowns associated with the prison drug trade. Although a comprehensive analysis of the pilot program is not yet available, preliminary data suggest the pilot has not achieved the desired outcomes. Specifically, the data suggests:

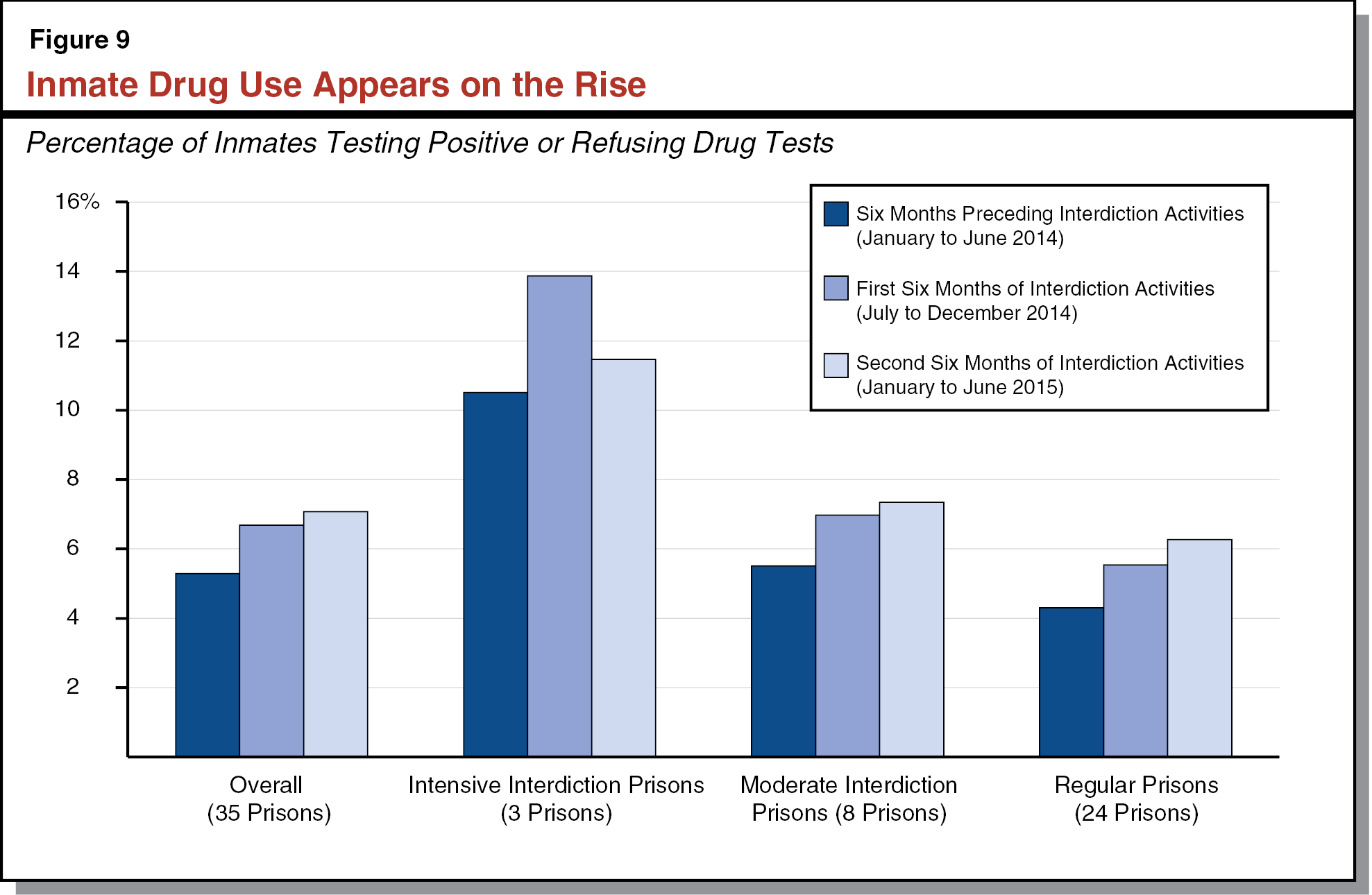

- Drug Use Appears on the Rise. As shown in Figure 9, data provided by CDCR indicate that the overall statewide percentage of positive and refused tests increased from 5.3 percent in the six months preceding the implementation of the interdiction strategies to 6.7 percent in the first six months of the pilot. (Refused tests are likely an indication that an inmate has been using drugs.) The largest increase occurred at the prisons which received the most intensive interdiction. The percent of positive or refused tests also increased in the second six months of the pilot overall at prisons receiving moderate interdiction resources. While there was a decline at intensive prisons between the first and second six month period of the pilot, the percent of positive or refused tests still remained above that of the six months preceding the pilot.

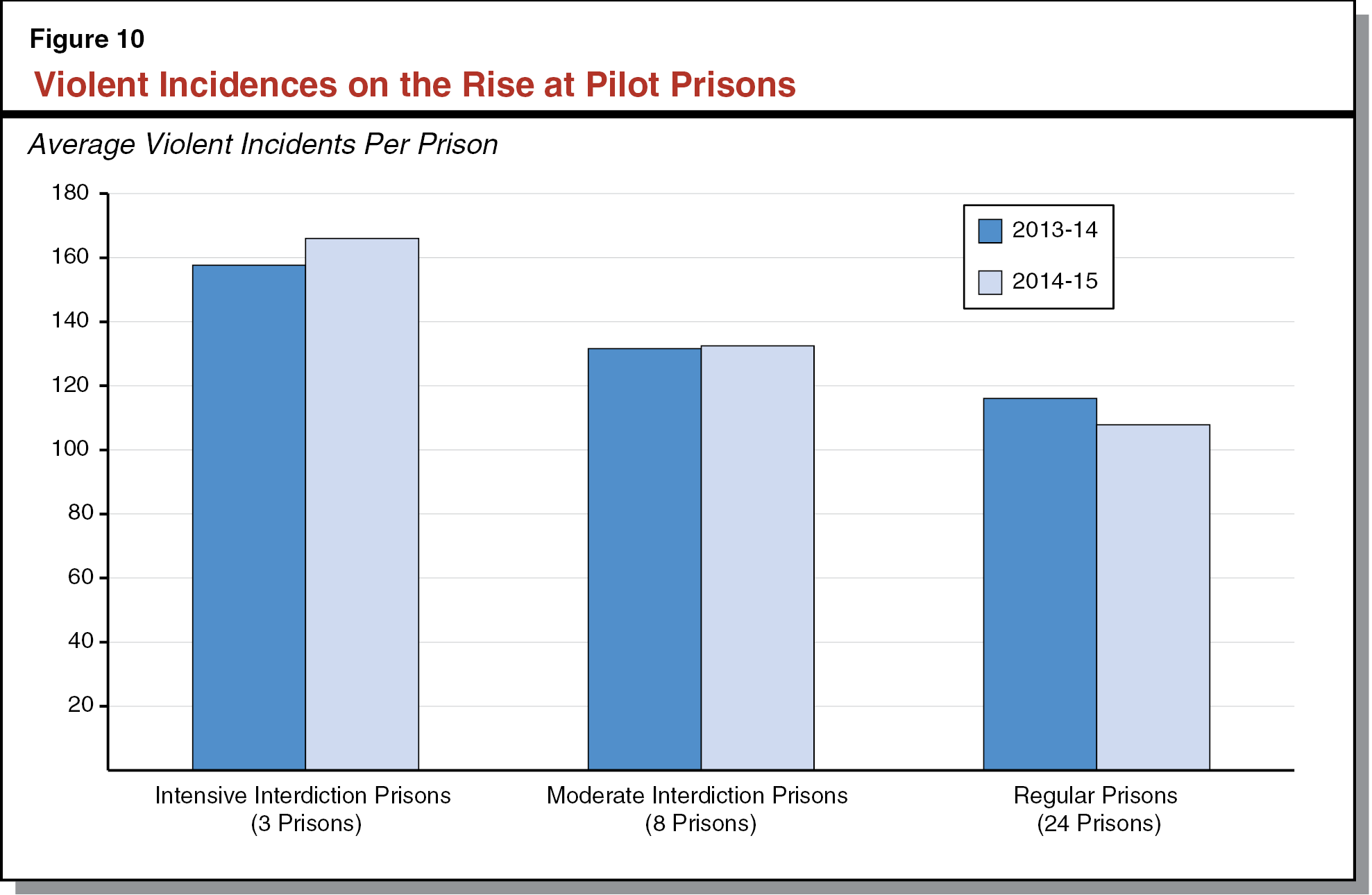

- Institutional Security Improvements May Not Be Attributable to Interdiction Efforts. Data provided by CDCR indicate that the number of violent incidents in prison (such as assaults on staff and other inmates) declined by about 4 percent from 2013–14 to 2014–15 (the first year of the drug interdiction pilot). However, as shown in Figure 10, most of this decline occurred in prisons without enhanced interdiction. Prisons which were part of the pilot actually saw an increase in violence. In addition, data provided by CDCR indicate that lockdowns decreased overall from 2013–14 to 2014–15 but that the decline in prisons without enhanced interdiction (45 percent) was greater than the decline in prisons with enhanced interdiction (36 percent).

Drug Testing Appears to Have Some Benefit. Data provided by CDCR suggest that random drug testing has increased the rate at which the department is identifying inmates who are using illegal drugs. This increased rate of identification should allow the department to better target inmates who are in need of substance abuse treatment. In addition, it is possible that the random drug testing is deterring some inmates from using drugs. However, further analysis is needed to determine whether this is the case.

LAO Recommendations

Approve Temporary Extension of Drug Testing. We recommend that the Legislature approve the portion of this request—$750,000 from the General Fund—associated with continuing the random drug testing for one additional year. The drug testing program appears to have increased the rate at which CDCR is identifying inmates who use illegal drugs. In addition, the collection of additional drug test results should help the department to assess whether the removal of drug interdiction resources, as we recommend below, affects the rate of drug use in prisons. Based on the result of the department’s final evaluation, the Legislature could determine whether to permanently extend the drug testing program.

Reject Remainder of Proposal to Extend Drug Interdiction Pilot Program. We recommend that the Legislature reject the remainder of the Governor’s proposal to extend and expand the drug interdiction pilot program. Extending the program now would be premature given that (1) preliminary data suggest that it is not achieving its intended outcomes and (2) CDCR has not yet fully evaluated its effectiveness. We also recommend that the Legislature direct the department to accelerate its timeline for evaluating the program so that it is completed in time to inform legislative deliberations on the 2017–18 budget, such as whether any of the interdiction strategies should be permanently adopted.

Housing Unit Conversions

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend that the Legislature reject the administration’s proposal for $5.8 million to fund increased staffing for CDCR’s Investigative Services Unit (ISU) from savings related to segregated housing unit conversions. This is because the proposal lacks sufficient workload justification, particularly in light of recent declines in other ISU workload.

Background

Segregated Housing Units. CDCR currently operates different types of celled segregated housing units that are used to hold inmates separate from the general prison population. These segregated housing units include:

- Administrative Segregation Units (ASUs). ASUs are intended to be temporary placements for inmates who, for a variety of reasons, constitute a threat to the security of the institution or the safety of staff and inmates. Typically, ASUs house inmates who participate in prison violence or commit other offenses in prison.

- Security Housing Units (SHUs). SHUs are used to house for an extended period inmates who CDCR considers to be the greatest threat to the safety and security of the institution. Historically, department regulations have allowed two types of inmates to be housed in SHUs: (1) inmates sentenced to determinate SHU terms for committing serious offenses in prison (such as assault or possession of a weapon) and (2) inmates sentenced to indeterminate SHU terms because they have been identified as prison gang members. (As discussed below, changes were recently made to CDCR’s regulations as a result of a legal settlement.)

Segregated housing units are typically more expensive to operate than general population housing units. This is because, unlike the general population, inmates in segregated housing units receive their meals and medication in their cells, which requires additional staff. In addition, custody staff are required to escort inmates in segregated housing when they are temporarily removed from their cells, such as for a medical appointment.

In 2015, CDCR settled a class action lawsuit, known as Ashker v. Brown, related to the department’s use of segregated housing. The terms of the settlement include significant changes to many aspects of CDCR’s segregated housing unit policies. For example, inmates can no longer be placed in the SHU simply because they are gang members. Instead, inmates can only be placed in the SHU if they are convicted of one of the specified SHU–eligible offenses following a disciplinary due process hearing. In addition, the department will no longer impose indeterminate SHU sentences. The department has also made changes to allow inmates to transition from segregated housing (including SHUs and ASUs) to the general population more quickly than before.

Investigative Services Unit. The CDCR currently operates an ISU consisting of 263 correctional officer positions located across the 35 state–operated prisons. Correctional officers who are assigned to the ISU receive specialized training in investigation practices. These staff are responsible for various investigative functions such as monitoring the activities of prison gangs and investigating assaults on inmates and staff.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget proposes to reduce General Fund support for CDCR by $16 million in 2015–16 and by $28 million in 2016–17 to account for savings from a reduction in the number of inmates housed in segregated housing units. According to the department, the policy changes it is implementing pursuant to the Ashker settlement will reduce the number of inmates held in ASUs and SHUs, allowing it to convert several of these units to less expensive general population housing units. For example, CDCR estimates that the number of inmates held in SHUs could decline by around 1,000, or about one–third of the current population.

In addition, the administration proposes $5.8 million to increase the number of staff in the ISU, which would offset the above 2016–17 savings. The redirected funding would support the addition of 48 correctional officers to the ISU, an increase of 18 percent. According to the administration, these positions are needed to handle workload from an anticipated increase in gang activity related to the new segregated housing policies required by the Ashker settlement. Specifically, the department plans to use the additional positions to monitor the activities of gang members released to the general population. The department is requesting 22 of the proposed positions be approved on a two–year, limited–term basis because it has not yet determined the exact amount of ongoing workload associated with the segregated housing policy changes.

Need for Additional ISU Staff Not Justified

Proposed ISU Staffing Increase Lacks Detailed Workload Analysis. While we acknowledge that the new segregated housing policies may drive some increased workload for the ISU, the department has not established a clear nexus between the policy changes and the increased workload. In particular, the department has been unable to provide a detailed analysis which indicates the specific workload increases that will result from the policy changes and how it was determined that 48 is the correct number of staff to handle this increased workload. Without this information it is difficult for the Legislature to assess the need for the requested positions.

Other Factors Have Impacted ISU Workload in Recent Years. There are a variety of factors that drive workload for the ISU, such as the number of violent incidences occurring in the prisons. It appears that a couple of these key factors have declined in recent years. First, the number of inmates in CDCR–operated prisons has decreased from about 124,000 in 2012–13 to a projected level of about 117,000 in 2015–16. Second, the number of assaults on inmates and staff has decreased from about 8,500 in 2012–13 to about 1,200 in 2014–15. Accordingly, the ISU now has fewer inmates to monitor and fewer assaults to investigate relative to 2012–13. Despite these developments, correctional officer staffing for the ISU has actually increased slightly from 253 officers in 2012–13 to 263 officers in 2014–15. This raises the question of whether any increased workload for the ISU resulting from segregated housing policy is offset by other workload decreases in recent years—meaning that potential workload increases could be accommodated with existing resources.

LAO Recommendation

We recommend that the Legislature reject the administration’s proposal for $5.8 million to fund increased staffing for the ISU because the proposal lacks sufficient workload justification, particularly in light of recent declines in other ISU workload.

Alternative Custody Programs

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend that the Legislature withhold action on the Governor’s proposal to reduce the length of the alternative custody programs pending additional information to determine whether the proposed change is warranted.

Background

As we discuss below, CDCR currently maintains two programs for certain inmates to serve the remainder of their sentence in an alternative custody setting—the Alternative Custody Program (ACP) and the Enhanced Alternative Custody Program (EACP).

ACP. Chapter 644 of 2010 (SB 1266, Lieu) created the ACP to allow certain inmates to be released from prison early and serve the remainder of their sentences in the community in a private residence or residential treatment facility under the supervision of a state parole agent. The program was initially intended to serve (1) female inmates, (2) pregnant inmates, and (3) inmates who were primary caretakers of dependent children prior to their incarceration. Eligibility was limited to inmates who (1) had no current or prior serious or violent crimes, (2) had no current or prior registerable sex offenses, (3) had not been assessed as posing a high risk to commit a violent crime, and (4) had not attempted to escape from custody within the last ten years. The Legislature enacted subsequent legislation which (1) excluded male inmates from the program and (2) amended the criminal history eligibility requirements. Specifically, Chapter 41 of 2012 (SB 1021, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) allowed female inmates with prior serious or violent crimes to participate in the program. (Inmates with current offenses for such crimes were still excluded.) Statute does not specify how much of their sentence inmates must complete in order to be eligible for ACP, but CDCR’s current regulations require that program participants must be within two years of their scheduled release date.

EACP. In 2014, a federal court ordered CDCR to expand the ACP in order to reduce prison overcrowding. In response, the department created the EACP. The EACP is similar to the ACP except that (1) inmates who have a current serious or violent offense are eligible and (2) participants are required to reside in one of three designated residential treatment facilities located in San Diego, Sante Fe Springs, and Bakersfield.

In 2015, a federal court found that the state was unlawfully discriminating against male inmates by excluding them from the ACP and ordered CDCR to make male inmates eligible for the program. This court order did not apply to the EACP.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget includes three proposals related to the department’s alternative custody programs:

- Expand EACP. The Governor’s budget proposes a $390,000 General Fund augmentation to expand female participation in EACP by 72 beds (36 beds at each of the existing facilities in San Diego and Sante Fe Springs). This would expand the total program capacity to 311.

- Extend ACP Eligibility to Male Offenders. The Governor’s budget proposes $3.3 million from the General Fund and 20 positions in 2015–16 to extend eligibility for the ACP to male inmates. Under the proposal, these levels would increase to $6 million and 40 positions beginning in 2016–17. According to the administration these resources are needed to (1) review applications from inmates to determine eligibility, (2) develop rehabilitation plans for eligible inmates, and (3) notify stakeholders (such as local law enforcement and victims) when inmates are scheduled for early release.

- Reduce Program Duration From Two Years to One. The administration also proposes to reduce the length of time inmates can participate in both the ACP and EACP from within two years of their scheduled release date to within one year from being released.

LAO Assessment

Proposals to Expand EACP and ACP Align With Court Orders . . . The Governor’s proposals to expand the EACP and allow male inmates to participate in the ACP appear to be aligned with recent court orders. For example, as discussed above, the federal court recently ordered CDCR to make male inmates eligible for the ACP.

. . . But Proposed Reduction in Program Length Not Justified. CDCR has not provided a rationale for why the alternative custody programs would operate more effectively as one–year programs rather than as two–year programs. Nor has the department fully evaluated the potential impact on the female alternative custody programs that would occur from the reduction in length. For example, the administration has been unable to provide data on the average time that female offenders currently spend in the alternative custody programs and how many female inmates could be affected by the change. Without the above information it is difficult for the Legislature to determine whether a reduction in the length of the alternative custody programs is appropriate.

LAO Recommendation

Withhold Action. In view of the above, we recommend that the Legislature withhold action on the Governor’s proposal to reduce the length of the alternative custody programs pending additional information to determine whether the proposed change is warranted. Accordingly, we also recommend that the Legislature direct the department to report at budget hearings on (1) why it believes the male ACP would operate more effectively as a one–year program and (2) its assessment of the impact of reducing the program length on female offenders.

While we find that the Governor’s proposal to expand the ACP and the EACP are aligned with recent court decisions, we recommend the Legislature hold off on approving the expansion pending resolution on the proposed change to program duration as a different level of funding may be required if program length is not reduced to one year. As part of the above report, CDCR should also provide information on the fiscal effects (relative to the Governor’s budget) of maintaining the current length of the program at two years.

Programs and Services for Long–Term Offenders

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend that the Legislature approve a portion of the proposal that increases rehabilitative programming opportunities for higher–risk offenders and reject the remainder of the proposal that would exclusively target long–term offenders. Research suggests that programs targeting higher–risk offenders are likely to achieve better outcomes than those targeting long–term offenders.

Background

Long–term offenders are individuals who have been sentenced to a life term in prison with the possibility of parole, with the Board of Parole Hearings (BPH) making the determination whether parole is ultimately granted. As a result of an increase in the rate at which BPH grants parole in recent years, the number of long–term offenders granted parole increased from 541 in 2009 to 902 in 2014. According to the department, due to the nature of their commitment offenses, long–term offenders spend a significant amount of time in prison and thus may have challenges adjusting to life outside of prison. In order to alleviate these challenges, CDCR has established rehabilitative programs that specifically target long–term offenders:

- Long–Term Offender Program (LTOP). The LTOP provides rehabilitative programming (such as substance use disorder treatment, anger management, and employment readiness) on a voluntary basis to long–term offenders at three state prisons—Central California Women’s Facility in Chowchilla, California Men’s Colony in San Luis Obispo, and California State Prison, Solano.

- Offender Mentorship Certification Program (OMCP). The OMCP trains long–term offenders as substance use disorder counselors while they are incarcerated. Upon graduation from the training program, participants are employed by CDCR to deliver counseling services to their fellow inmates. There are currently two sessions offered annually, allowing up to 64 offenders to be certified as mentors each year.

In addition, CDCR offers various other rehabilitative programs that are generally available to inmates and parolees, including long–term offenders. The current year budget allocates about $450 million for these programs, which include education, substance use disorder treatment, and cognitive behavioral therapy. As we discuss below, the Governor proposes expanding some of these programs including:

- Parole Service Centers (PSCs). PSCs are located throughout the state and provide residency, employment, and other support services to parolees. The CDCR currently has 136 beds in PSCs dedicated to long–term offenders. The current–year budget for PSCs is $12 million.

- Transitions Program. The Transitions Program utilizes contract providers to provide various life and job skills training to help offenders transition back into their communities. Under the program, which is located at 13 prisons, all inmates—including long–term offenders—are eligible to participate if they (1) have been assessed as a moderate–to–high risk to reoffend, (2) have been assessed as having a moderate–to–high need for employment training services, and (3) have between five weeks and six months left on their sentence. The current–year budget for the Transitions Program is $3.2 million.

- Community College Programs. Chapter 695 of 2014 (SB 1391, Hancock) required CDCR to enter into an interagency agreement with California Community Colleges to expand community college courses offered in prisons. Under this program, CDCR provides classroom space and equipment, while the community colleges provide staff, faculty, and volunteers to teach the courses. There are currently 14 community colleges offering courses to around 7,500 inmates. According to CDCR, 38 percent of inmates currently enrolled in the college programs are long–term offenders.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget for 2016–17 proposes a $10.5 million General Fund augmentation for CDCR to expand the availability of programs for long–term offenders. The proposed augmentation would increase to $13.5 million in 2017–18 and $16.2 million in 2018–19, as shown in Figure 11. The proposal includes both the expansion of existing programs and the establishment of new programs for long–term offenders. As we discuss below, while some of the programs specifically target long–term offenders, other programs target a broader range of offenders. The proposed $10.5 million increase in 2016–17 would be allocated for the following programs:

- LTOP ($3.4 Million). The budget proposes $3.4 million to expand the LTOP to a fourth prison yet to be determined. Of this amount, $2.1 million is one–time funding for the installation of modular space for the program and $1.3 million would support ongoing administrative costs.

- PSCs ($3.1 Million). The budget proposes $3.1 million to double the number of PSC beds dedicated to long–term offenders—from 136 beds to 272 beds.

- Transitions Program ($3.1 Million). The budget proposes $3.1 million to expand the Transitions Program to the remaining 21 state prisons that currently do not offer the program. In addition, the department proposes to terminate its existing contracts and instead hire 53 civil service teachers to deliver services. According to CDCR, this modification would help prisons address challenges they have faced procuring contract providers for the program.

- Community College Programs ($480,000). The budget proposes $480,000 to support overtime for custody staff to monitor inmates participating in community college courses.

- OMCP ($423,000). The budget proposes $423,000 to double the number of (1) annual OMCP training sessions from two to four and (2) potential annual program graduates from 64 to 128.

Figure 11

Governor’s Long–Term Offender Proposal

(In Millions)

|

Program |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

|

Long–Term Offender Program |

$3.4 |

$1.3 |

$1.3 |

|

Parole Service Centers |

3.1 |

3.1 |

3.1 |

|

Transitions Program |

3.1 |

3.1 |

3.1 |

|

Community College Program |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

Offender Mentor Certification Program |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

|

Transitional Housing Program |

— |

5.1 |

7.8 |

|

Totals |

$10.5 |

$13.5 |

$16.2 |

As shown in the figure, the proposed $10.5 million augmentation would increase in 2017–18 and 2018–19. Part of this increase would support the establishment of a new Transitional Housing Program for long–term offenders while they are on parole. The requested funding would allow CDCR to contract for residency and rehabilitative services for 400 long–term offenders upon full implementation.

LAO Assessment

Targeting Higher–Risk Offenders Yields Greater Public Safety Benefits. Research shows that programs designed to reduce recidivism are most effective when they target offenders who have been assessed as a moderate–to–high risk to reoffend. This is because lower–risk offenders are much less likely to reoffend irrespective of whether they receive programming, resulting in little public safety benefits. Long–term offenders are typically considered lower–risk offenders compared to the general population. This is because they are (1) subject to an exhaustive review by BPH and are not granted release if they are deemed to pose a high risk to reoffend and (2) are on average older than most inmates who are released. Research has demonstrated that as offenders age they become less likely to commit crimes.

Only Portion of Proposed Funding Targets Higher–Risk Offenders. Since most of the increased funding proposed by the Governor would support programs that specifically target long–term offenders—which tend to be of lower risk—only a small portion of the funds would be available to help support higher–risk offenders. Specifically, we find that three of the programs proposed for augmentation would increase programming opportunities for higher–risk offenders. These include: (1) the expansion of the OMCP, (2) the expansion and modification of the Transitions Program, and (3) custody overtime needed to support community college programs. We also note that these programs incorporate best practices that have been demonstrated through research to be cost–effective strategies for reducing recidivism, such as targeting rehabilitative needs including substance abuse treatment and job training. While the OMCP trains only long–term offenders as counselors, it increases programming opportunities for other inmates because the counselors are employed by CDCR to deliver substance abuse treatment disorder counseling to their peers.

Many Higher–Risk Offenders Not Currently Receiving Needed Treatment. Currently, many inmates who have been assessed as a moderate–to–high risk to reoffend do not receive rehabilitative programming. For example, in 2014–15, 44 percent of such offenders were released without having any of their rehabilitative needs met, despite having been assessed as having a need for programming. This is in large part due to limited resources. Given that most of the Governor’s proposal targets long–term offenders, it will do little to meet the needs of higher–risk offenders.

LAO Recommendations

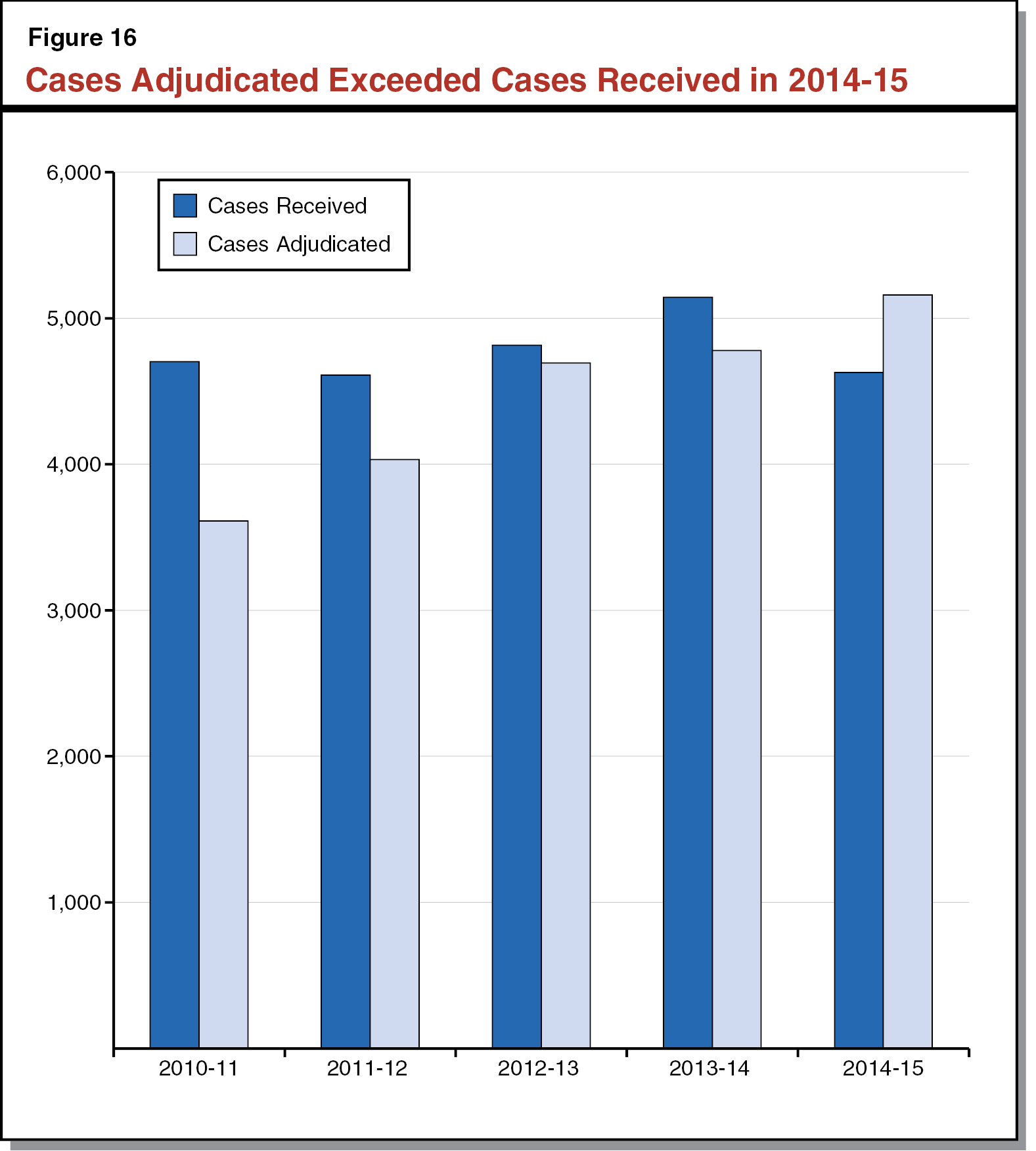

Approve Proposed Expansion of Programming for Higher–Risk Offenders. We recommend that the Legislature approve the portion of the proposal—totaling $4 million—that would expand rehabilitative programming opportunities for higher–risk offenders that are consistent with programs shown to be cost–effective methods for reducing recidivism. Specifically, we recommend providing the requested funding to support (1) the expansion of the OMCP, (2) the expansion and modification of the Transitions Program, and (3) custody overtime needed to operate community college programs.