November 14, 2013

Pursuant to Elections Code Section 9005, we have reviewed the

proposed constitutional and statutory initiative (A.G. File No. 13‑00

22) relating to conditions for amending, repealing, replacing, or

rendering inoperative the Medi-Cal Hospital Reimbursement Improvement

Act of 2013—current law that concerns the imposition of fees on certain

private hospitals.

Background

Overview of Medi-Cal

Medi-Cal Administration and Coverage. The

federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) administers the

federal Medicaid Program. In California, this federal program is

administered by the state Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) as

the California Medical Assistance Program, and is known more commonly as

Medi-Cal. This program currently provides health care benefits to about

7.9 million low-income persons who meet certain eligibility requirements

for enrollment in the program (hereafter referred to as the currently

eligible population). Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care

Act (ACA), also known as federal health care reform, the state will

expand Medi-Cal to cover over one million low-income adults who are

currently ineligible (hereafter referred to as the expansion

population), beginning January 1, 2014.

Medi-Cal Financing. The costs of the

Medicaid Program are generally shared between states and the federal

government based on a set formula. The federal government’s contribution

toward reimbursement for Medicaid expenditures is known as federal

financial participation (FFP). The percentage of Medicaid costs paid by

the federal government is known as the federal medical assistance

percentage (FMAP).

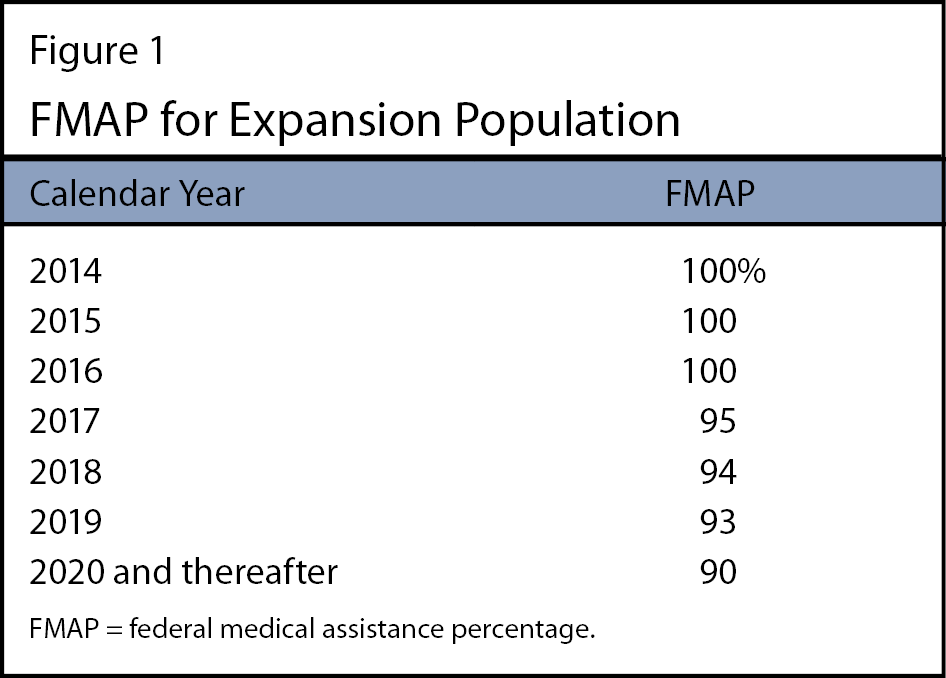

In general, the FMAP for Medi-Cal costs associated with the currently

eligible population has been set at 50 percent. (However, for certain

currently eligible subpopulations and certain administrative activities,

the state receives a higher FMAP percent.) As Figure 1 shows (see next

page), for three years beginning January 1, 2014, the FMAP for nearly

all Medi-Cal costs associated with the expansion population will be 100

percent. Beginning January 1, 2017, the FMAP associated with the

expansion population will decrease over a three-year period until

reaching 90 percent on January 1, 2020, where it will remain thereafter

under current federal law.

Federal Medicaid law permits states to finance the nonfederal share

of Medicaid costs through several sources, including (but not limited

to):

- State General Funds. State general

funds are revenues collected primarily through personal income,

sales, and corporate income taxes.

- Charges on Health Care Providers.

Federal Medicaid law permits states to (1) levy various types of

charges—including taxes, fees, or assessments—on health care

providers and (2) use the proceeds to draw down FFP to support their

Medicaid programs and/or offset some state costs. These charges must

meet certain requirements and be approved by CMS for revenues from

these charges to be eligible to draw down FFP. A number of different

types of providers can be subject to these charges, including

hospitals.

Medi-Cal Delivery Systems. Medi-Cal

provides health care through two main systems: fee-for-service (FFS) and

managed care. In the FFS system, a health care provider receives an

individual payment directly from DHCS for each medical service delivered

to a beneficiary. In the managed care system, DHCS contracts with

managed care plans to provide health care for Medi-Cal beneficiaries

enrolled in these plans. Managed care enrollees may obtain services from

providers—including hospitals—that accept payments from the plans. The

DHCS reimburses plans with a predetermined amount per enrollee, per

month (known as a capitation payment) regardless of the number of

services each enrollee actually receives.

Medi-Cal Hospital Financing

About 400 general acute care hospitals licensed by the state

currently receive at least one of three types of payments Medi-Cal makes

to pay for services for patients. As follows, these hospitals are

divided into three categories based on whether the hospital is privately

owned or publicly owned, and who operates the hospital.

- Private Hospitals. These are hospitals

owned and operated by private corporations.

- District Hospitals. These are public

hospitals owned and operated by municipalities and health care

districts.

- County Hospitals and University of California (UC)

Hospitals. These are public hospitals owned and

operated by counties or the UC system.

Below we describe the three types of payments—direct payments,

supplemental payments, and managed care payments—that Medi-Cal makes for

hospital services.

Direct Payments. Direct payments are

payments for services provided to Medi-Cal patients through FFS. The

nonfederal share of Medi-Cal direct payments to private and district

hospitals is funded from the state General Fund, while the nonfederal

share of direct payments to county and UC hospitals is self-funded.

Supplemental Payments. Supplemental

payments (considered a type of FFS payment) are made in addition to

direct payments. Medi-Cal generally makes supplemental payments to

hospitals periodically on a lump-sum basis, rather than individual

increases to reimbursement rates for specific services. There are

various types of supplemental payments related to hospital services

provided to Medi-Cal patients, including a category of payments to

private hospitals known as Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH)

replacement payments that we discuss further later in this analysis.

Depending on the type of supplemental payment, the nonfederal share may

be comprised of General Fund support, revenues from charges levied on

hospitals, or other state and local funding sources.

Managed Care Payments. Managed care

payments are payments from managed care plans to providers for services

delivered to Medi-Cal patients enrolled in these plans. The capitation

payments that plans receive from DHCS are meant to cover the expected

costs to plans from making payments to providers, including hospitals.

The nonfederal share of capitation payments to managed care plans is

comprised of General Fund support, charges levied on hospitals, and

other state and local funding sources.

Federal Limits on FFS Hospital Payments.

Federal regulations specify that to be eligible for FFP, the total

amount of Medi-Cal FFS payments to private hospitals—that is, the sum of

all direct and supplemental payments for private hospital services—may

not exceed a maximum amount known as the upper payment limit (UPL).

(There are separate UPLs that apply to payments to hospitals owned and

operated by local governments such as counties, and hospitals owned and

operated by the state such as UC hospitals.) The UPL is a statewide

aggregate ceiling on FFS payments to all private hospitals. This means

there are no limits on FFS payments to individual private hospitals, as

long as total FFS payments to all private hospitals do not exceed the

UPL. In California, the UPL for hospital services has historically been

between 5 percent to 10 percent above the total costs incurred by

hospitals from providing these services, as defined under cost-reporting

procedures approved by CMS.

Federal Limits on Managed Care Hospital Payments.

The UPL does not apply to managed care payments for hospital

services. However, federal Medicaid law requires qualified actuaries to

certify capitation payments to managed care plans as being “actuarially

sound” before these payments may receive FFP. This certification

involves the actuaries’ assessment that capitation payments reflect

“reasonable, appropriate, and attainable” costs to plans from making

payments to providers, including hospitals. In practice, actuarial

soundness requirements directly limit the total amount of capitation

payments that DHCS may make to plans, and thus indirectly limit the

total amount of payments that plans may make to hospitals.

Hospital Quality Assurance Fee

Chapter 657, Statutes of 2013 (SB 239, Hernandez), enacts the

Medi-Cal Hospital Reimbursement Improvement Act of 2013 (hereafter

referred to as the Act). The Act imposes a charge known as a quality

assurance fee (hereafter referred to as the fee) on certain private

hospitals beginning January 1, 2014.

If approved by CMS and implemented, the fee imposed by the Act will

constitute the fourth consecutive hospital quality assurance fee program

implemented in California since 2009 (each of the prior three programs

had a statutory sunset date). The fee program authorized under the Act

is broadly similar in structure to the prior three fee programs. The Act

establishes a general structure for (1) how the fee is to be assessed

and (2) how the proceeds from the fee are to be spent. We describe both

components of this structure below.

Fee Assessment. Under the Act, the state

will assess the fee for each inpatient day at each private hospital. The

fee rate per inpatient day will vary depending on payer type, with the

highest rates assessed on Medi-Cal inpatient days and lower rates

assessed on days paid for by other payers, such as private insurance.

The fee rate ranges from $145 for each inpatient day covered by a

non-Medi-Cal payer to $618 per inpatient day covered by Medi-Cal.

Private hospitals will pay the fee in quarterly installments.

Use of Fee Moneys to Offset State Costs.

Under the Act, DHCS will administer and collect the fee from hospitals

and deposit the proceeds into the Hospital Quality Assurance Revenue

Fund. Moneys in this fund—the proceeds of the fee and any interest

earned on the proceeds—are available only for certain purposes. These

purposes include the following that serve to offset state costs (in

order of descending priority):

- Up to $1 million of the moneys annually will be allocated to

reimburse DHCS for the staffing and administrative costs related to

implementing the fee.

- A certain portion of the moneys (determined by a formula) will

offset General Fund costs for providing children’s health care

coverage, thereby achieving General Fund savings. Later we describe

how the allocation for this General Fund offset is to be determined

under the Act.

Use of Fee Moneys for Quality Assurance Payments.

After moneys in the fund are allocated to offset state costs,

the remaining moneys are available to support payment increases to

hospitals, collectively known as quality assurance payments (in order of

descending priority).

- A large portion of the moneys will provide the nonfederal share

of certain increases to capitation payments to managed care plans,

up to the maximum actuarially sound amount permitted by federal law.

The plans are required to pass along these capitation increases

entirely to private hospitals, county hospitals, and UC hospitals.

- A large portion of the moneys will provide the nonfederal share

of certain supplemental payments to private hospitals, bringing

total FFS payments to private hospitals as close as possible to the

UPL.

- Some of the moneys may be used to fund direct grants to public

hospitals. Any grant amounts retained by public hospitals are not

considered Medi-Cal payments, and thus are not eligible for FFP.

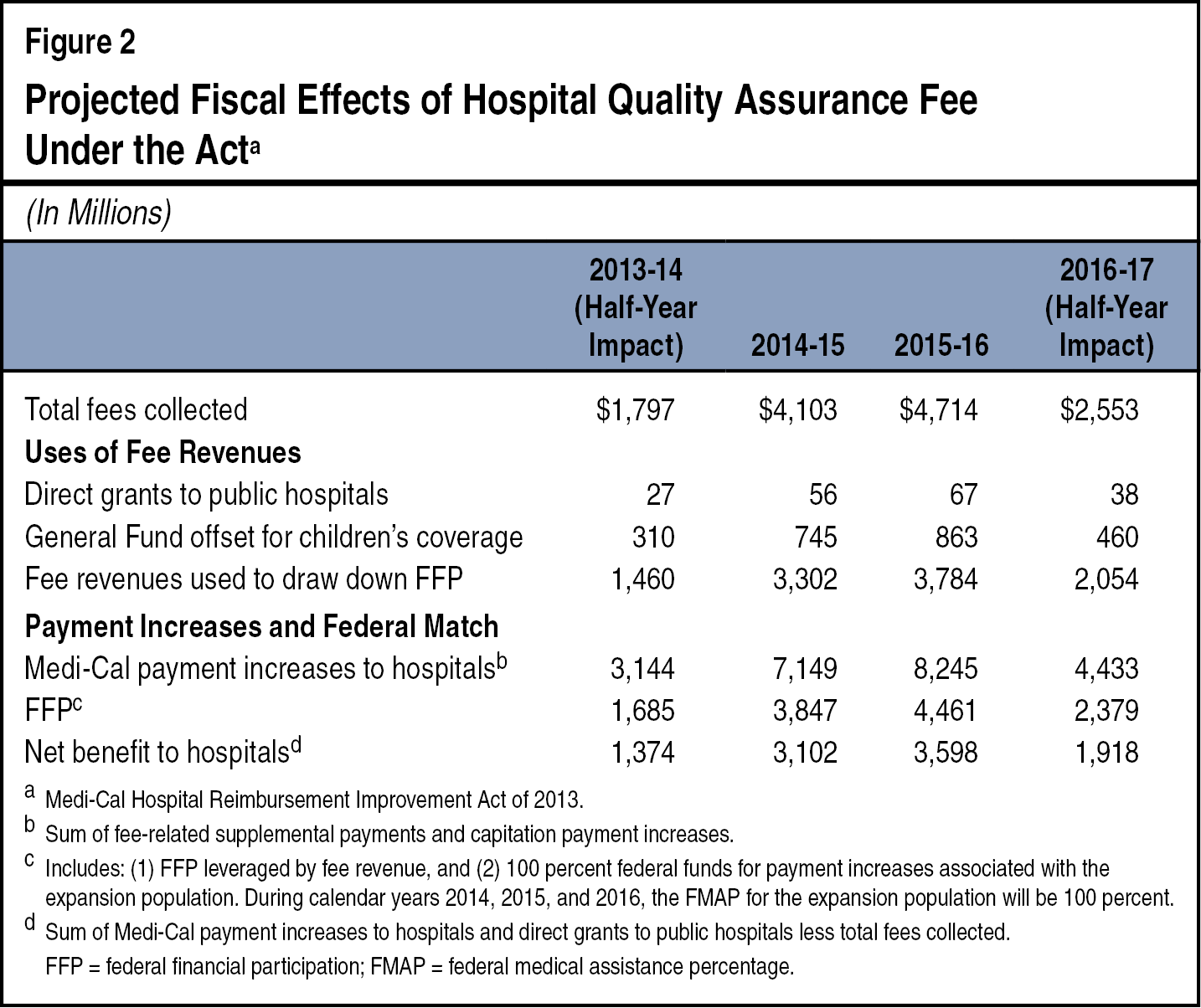

At the end of this background discussion, Figure 2 (see page 7)

displays our detailed projections of the annual amounts of fee moneys

used to offset state costs and support quality assurance payments to

hospitals under the Act.

Net Benefit and General Fund Offset for Children’s

Coverage. Under the Act, beginning July 1, 2014, the

annual amount of moneys used to offset General Fund costs for children’s

health care coverage will equal 24 percent of the “net benefit” to

hospitals, hereafter referred to as net benefit. (For the period between

January 1, 2014 and June 30, 2014, the amount of General Fund offset is

set at $155 million per quarter rather than a percentage of the net

benefit.) The Act defines net benefit as total fee revenue collected

from hospitals in each fiscal year, minus the sum of the following

quality assurance payments:

- Fee-funded supplemental payments and direct grants.

- Fee-related capitation increases for hospital payments.

Fee-related capitation increases consist of (1) fee-funded increases

related to hospital services for the currently eligible population and

(2) increases related to hospital services for the expansion population.

Due to the enhanced FMAP for the Medi-Cal expansion, the net benefit

from a capitation increase for the expansion population is generally

greater than the net benefit from an equal increase for the currently

eligible population. For example, a capitation increase of $100 million

for the currently eligible population would result in a net benefit of

roughly $50 million, since hospitals would provide the nonfederal share

for this increase through fee revenue. In contrast, the net benefit from

a capitation increase of $100 million for the expansion population would

be between $90 million and $100 million, depending on the FMAP in effect

for the year in question.

Fee Program Periods. The Act (1) specifies

the schedule of fee rates for the period between January 1, 2014 and

December 31, 2016, and (2) requires DHCS to periodically redevelop the

schedule of fee rates thereafter. Each schedule of fee rates will apply

to separate and consecutive “program periods,” each lasting no more than

three years. While the schedules may differ by program period, each

schedule will conform to the general structure for assessing the fee and

using the proceeds as specified in the Act. That is, for each program

period, DHCS will develop a schedule of fee rates that: (1) varies per

inpatient day by payer type, with higher rates assessed on Medi-Cal

days, and (2) enables the maximum amount of supplemental payments and

capitation increases for hospital payments that receive FFP.

The Act designates the period of January 1, 2014 through December 31,

2016 as the first program period, and the period of January 1, 2017

through June 30, 2019, as the second program period. Under the Act, DHCS

will determine the duration of subsequent program periods. During the

first program period, moneys in the Hospital Quality Assurance Revenue

Fund will be continuously appropriated without further legislative

action. In subsequent program periods, the Legislature will authorize

expenditures from the fund in the annual budget act.

FFS Maintenance-of-Effort (MOE) for Hospital Services.

The Act contains a provision to ensure that fee-related

moneys are used to supplement and not supplant existing funding for

hospital services provided to Medi-Cal patients. Specifically, the Act

stipulates that for hospital services provided to Medi-Cal patients

through FFS on or after January 1, 2014, the total amount of payments

supported by General Fund expenditures shall not be less than the total

amount that would have been paid for the same services on December 1,

2013. The Act specifically exempts DSH replacement payments from this

MOE requirement. We estimate that for the 2012‑13 fiscal year, the state

provided $2 billion in General Fund expenditures for the types of FFS

payments subject to the Act’s MOE requirement.

Conditions Rendering Fee Inoperative. The

Act includes several poison pill provisions specifying certain

conditions that would render the Act inoperative, including, but not

limited to:

- A judicial determination by the State Supreme Court or a State

Court of Appeal that revenues from the fee must be included for

purposes of calculating the Proposition 98 funding level required

for schools. We describe the Proposition 98 funding requirement

later in this analysis.

- A lawsuit related to the Act results in a General Fund cost of

at least 0.25 percent of General Fund expenditures authorized in the

most recent annual budget act (about $240 million in 2013‑14).

Absent conditions that would trigger the Act’s poison pill provisions

and render the Act inoperative, the Act becomes inoperative by its terms

as of January 1, 2017, due to a sunset provision. Therefore, under

current law, the fee will be in place only through the first program

period. (Moreover, authorization of the Hospital Quality Assurance

Revenue Fund expires on January 1, 2018.) However, as noted, the Act

prescribes a general structure for assessing the fee and using the

proceeds that would apply to subsequent program periods if legislation

were enacted to both extend the fee and maintain the fund.

Projected Fiscal Effects of the Act. Figure

2 provides our projections of (1) total fees collected as authorized by

the Act, (2) uses of the fee revenues under the Act, and (3) fiscal

effects on the state and hospitals of the Act.

Proposal

This measure would amend the State Constitution to (1) restrict the

Legislature’s ability to amend, repeal, or replace the Act by statute,

and (2) require voter approval to amend or replace the Act outside of

these restrictions. The measure would also amend by statute the Act’s

poison pill provisions and remove the Act’s sunset provision. The

measure would also remove the Act’s poison pill provision related to

Proposition 98, and amend the Constitution to specify that revenues from

the fee imposed by the Act and all interest earned thereon shall not be

considered as revenues subject to the Proposition 98 funding requirement

calculation. Below we describe the specific amendments that the measure

would place in the Constitution, and then describe the statutory

amendments that the measure would enact.

Constitutional Amendments

Requirements for Amending, Repealing, or Replacing the

Act. This measure amends the Constitution to require

two-thirds majorities in both houses of the Legislature to pass any

statute that repeals the Act in its entirety. In addition, any statute

that amends or replaces the Act requires voter approval in a statewide

election before taking effect, unless both of the following conditions

are met:

- The Legislature passes the statute with two-thirds majorities in

both houses.

- The statute (1) is necessary for securing federal approval to

implement the fee program, or (2) only changes the methodology used

for developing the fee or quality assurance payments.

We note that under current law, the Legislature may pass legislation

to broadly amend or repeal the Act with simple majorities in both

houses, although some amendments could require passage by two-thirds

majorities in both houses.

Fee Proceeds and Interest Exempt From Proposition 98

Calculation. Proposition 98, a constitutional amendment

adopted by voters in 1988 and amended in 1990, established a set of

formulas that are used to annually calculate a minimum state funding

level for K-12 education and the California Community Colleges. In many

cases, additional state General Fund revenues result in a higher

Proposition 98 funding requirement. This measure amends the Constitution

to specify that the proceeds of the fee and all interest earned on such

proceeds shall not be considered in calculating the Proposition 98

funding level required for schools.

Statutory Amendments

Changes to Poison Pill Provisions. The

measure amends the Act’s poison pill provisions in the following ways:

- The measure deletes the provision triggered by a state judicial

determination that revenues from the fee are subject to the

Proposition 98 calculation. As noted earlier in this analysis, the

measure amends the Constitution to specify that proceeds and

interest from the fee are not subject to the Proposition 98

calculation, thereby precluding such a judicial determination.

- The measure inserts a new poison pill provision that renders the

Act inoperative if the Legislature does not appropriate moneys in

the Hospital Quality Assurance Revenue Fund within 30 days following

enactment of the annual budget act.

- The measure amends the provision triggered by a General Fund

cost from a lawsuit related to the Act. Specifically, the measure

redefines the threshold cost to be an overall net cost to the

General Fund due to the Act remaining operative, rather than 0.25

percent of General Fund expenditures authorized in the budget act.

Removal of Sunset Provisions. The measure

deletes the Act’s sunset provision. The measure also nullifies the

current-law sunset of the Hospital Quality Assurance Revenue Fund, and

instead specifies that the fund shall remain operative as long as the

Act remains operative. These combined changes permanently extend the fee

program under the Act—starting with the second program period—absent one

of the following conditions being met.

- An event occurs that triggers one of the Act’s poison pill

provisions (as amended by the measure).

- Additional statute that amends, repeals, or replaces the Act is

adopted and takes effect in accordance with the measure’s

Constitutional requirements.

Fiscal Effects

Significant Ongoing Fiscal Benefits to

State and Local Governments in Future Years

Continuation of Fee-Related Fiscal Benefits.

Under current law, the Act becomes inoperative on January 1,

2017. As a result, both the imposition of the fee and its related fiscal

effects are currently scheduled to end with the first program period. By

removing the Act’s sunset provision, the measure provides the authority

for implementation of the fee to continue without interruption through

subsequent program periods. Implementation of the fee across program

periods would be governed by the Act’s general structure for assessing

the fee and using the proceeds. Thus, following the first six months of

2016‑17, the measure would maintain ongoing significant fiscal benefits

to state and local governments that otherwise would cease to exist under

current law.

Specifically, barring conditions that would trigger the Act’s poison

pill provisions, the measure would permanently extend the following

fiscal benefits to the state and local governments.

- General Fund offset for children’s coverage. Under the Act’s

current provisions (continued by this measure), annual state savings

would be equal to 24 percent of the fee’s net benefit.

- Direct grants, capitation increases, and other quality assurance

payments that benefit counties, the UC system, health care

districts, and other units of government that own and operate public

hospitals.

Estimated Level and Growth of Fiscal Benefits.

For each year, the exact amount of fiscal benefits to state and

local governments would depend on the total amount of fee revenue

collected, the amount of quality assurance payments made to hospitals,

and the resulting calculation of net benefit. As these factors are

currently unknown and their estimation subject to some uncertainty, to

project the measure’s fiscal impact, we rely on assumptions about the

annual growth in federally allowable quality assurance payments to

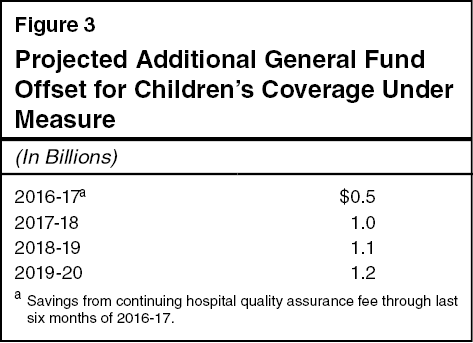

hospitals. Figure 3 (see next page) summarizes our multiyear projection

of the measure’s fiscal effect on the state General Fund by providing

fee revenues that offset state General Fund costs for children’s

coverage. We estimate that the General Fund offset for children’s

coverage would be around $500 million during the last six months of

2016‑17, reach more than $1 billion by 2019‑20, and grow between 5 to 10

percent annually thereafter. We also estimate that quality assurance

payments to state and local public hospitals would be around $90 million

during the last six months of 2016‑17, reach around $250 million by

2019‑20, and grow between 5 percent to 10 percent annually thereafter.

Below we discuss some considerations that affect our estimates.

Federal Sources of Uncertainty

We briefly highlight potential federal decisions that, if

implemented, could lead to significant deviations from our estimates of

the measure’s fiscal effects.

Allowable Rate of Provider Charges. Federal

regulations currently discourage states from levying provider charges

that exceed 6 percent of net patient revenue. Historically, hospital fee

programs in California have approached this threshold by assessing fees

as high as 5.5 percent of net patient revenue. We note that states have

previously litigated and successfully blocked regulations promulgated by

CMS that would have reduced the allowable rate of provider charges. If

the federal government were to successfully reduce permissible provider

charges—for example, to 3 percent rather than 6 percent of net patient

revenue—this could significantly lower estimated annual savings within

our multiyear projection. Such a change would also affect our estimate

of savings growth beyond 2019‑20.

Oversight of Quality Assurance Payments.

Federal cost containment strategies could also affect the amount of

quality assurance payments available under the fee. For example, changes

in federal Medicaid policy governing UPL calculations would affect

supplemental payments. As another example, CMS has expressed its

intention to tighten its oversight of capitation payment development in

Medicaid managed care and “look under the hood” of states’ actuarial

certification practices. Although it is difficult to quantify the

overall impact of these scenarios on quality assurance payments given

the varying forms such restrictions could take, they would generally

lead to lower net benefits to hospitals under the fee program, and thus

lower estimated savings to state and local governments from adopting the

measure.

Summary of Fiscal Effects

We estimate that the measure would result in the following major

fiscal impacts:

- State savings from increased revenues that offset state costs

for children’s health coverage of around $500 million beginning in

2016‑17 (half-year savings) to over $1 billion annually by 2019‑20,

likely growing between 5 percent to 10 percent annually thereafter.

- Increased revenues to support state and local public hospitals

of around $90 million beginning in 2016‑17 (half-year) to $250

million annually by 2019‑20, likely growing between 5 percent to 10

percent annually thereafter.

Return to Initiatives

Return to Legislative Analyst's Office Home Page