April 29, 2011

Pursuant to Elections Code Section 9005, we have reviewed

the proposed constitutional initiative regarding retirement benefits for state

and local employees (A.G. File No. 11‑0007, Amdt. #1NS). (Below, these employees

are referred to as "public employees"—a term that, for the purposes of this

analysis, excludes military and civilian employees of the U.S. Government who

reside in California.)

Background

Public Employee Retirement Benefits

Pension Benefits. The State Constitution

and statutes authorize the establishment of systems to provide pension and other

benefits to retired public employees, as well as public employees retiring with

certain disabilities and survivors of public employees. Currently, about

4 million Californians—11 percent of the population—are members of one or more

of the state's 85 defined benefit public pension systems, including 1 million

who currently receive benefit payments. Most California public employees

(including some part-time employees) are eligible to earn "defined benefit"

pensions—pensions that pay a specific amount after retirement that is generally

based on the employee's age at retirement, years of service, salary, and type of

work assignment. For example, a typical state office worker who retires this

year with five or more years of service is eligible for a defined benefit

pension at age 55 equal to 2 percent of his or her highest single working year's

salary multiplied by the number of years of service upon retirement (known as

the "2 percent at 55" benefit formula). Therefore, after working for 25 years,

such a retiree would be eligible to receive at age 55 a defined benefit roughly

equal to 50 percent of his or her highest single year's pay.

In the last few years, based on negotiations between the

Governor and state employee unions, pension benefits for newly hired state

employees—who will begin to retire in large numbers several decades from

now—have been lowered. Newly hired state office workers today, for instance,

typically are eligible for a defined benefit pension at age 60 equal to

2 percent of their highest average monthly pay rate during any 36 consecutive

months of employment. This "2 percent at 60" benefit formula costs less than the

2 percent at 55 formula described above. Like the 2 percent at 55 formula, the

benefits in the 2 percent at 60 formula grow with more advanced ages as well,

such that waiting to retire until age 63 or later can result in a defined

benefit pension equal to about 2.4 percent of the highest three years' pay. Some

local government employee groups have agreed to similar reductions in pension

benefits.

Local government employees often have different pension

formulas than those applicable to state employees—sometimes higher and sometimes

lower. Teachers and administrators in California's public schools and community

colleges, for example, generally are eligible for a defined benefit pension at

age 60 equal to 2 percent of their "final compensation" multiplied by their

number of years of service before retirement through the California State

Teachers' Retirement System (CalSTRS). For teachers, "final compensation" is the

highest single year's pay if they have 25 or more years of service and the

highest average annual pay over 36 consecutive months for most others. In

general, CalSTRS members are not eligible for Social Security benefits through

the federal government.

State and local office workers and teachers sometimes are

eligible for somewhat higher pension benefits if they delay their retirement a

few years after age 60. In the 2 percent at

55 formula described above, for example, state office workers retiring at age 63

may be eligible for a pension equal to 2.5 percent of their highest single

working year's salary multiplied by their years of service. Similarly, the basic

CalSTRS benefit formula grows to provide a 2.4 percent benefit multiplied by

years of service at age 63.

Peace officers and other public safety employees often

are eligible for larger state or local pensions than other public employees. For

example, a typical state correctional officer who retires this year with five or

more years of service is eligible for a defined benefit pension at age 50 equal

to 3 percent of his or her highest single working year's salary multiplied by

the number of years of service upon retirement (known as the "3 percent at 50"

benefit formula). Therefore, after working for 25 years, such a retiree would be

eligible to receive a defined benefit roughly equal to 75 percent of his or her

highest single year's pay. As with other state workers, based on union

negotiations with the Governor and approval by the Legislature, pension benefits

for newly hired state peace officers have been lowered. Newly hired state

correctional officers today, for instance, typically are eligible for a defined

benefit pension at age 55 equal to 2.5 percent of his or her highest average

monthly pay rate during any 36 consecutive months of employment. Many state and

local peace officers also do not receive Social Security benefits from the

federal government.

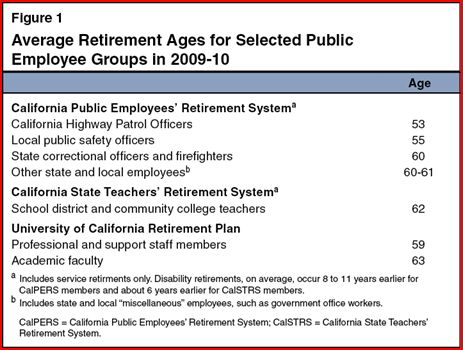

Typical Retirement Age. In most cases, public

employees with several years of service become eligible for a pension benefit at

age 50—even though the employee may be able to earn a greater pension benefit if

he or she delays retirement until a later age. In the state's three largest

public pension systems, the average state or local employee retires at about age

60 (see Figure 1). Due to recent changes in benefits for newly hired state

employees, the average retirement ages of state employees will tend to increase

somewhat in the coming decades compared to the data shown in Figure 1.

Other Ways to Earn Benefits. For the most

part, public employees earn pension benefits based on their base salary—that is,

as a certain percentage of their base salary during a specified number of years

in their career. Overtime earnings provided as a supplement to base pay

generally do not affect the pension benefits of public employees. There are,

however, a few other ways that some groups of public employees earn pension

benefits. In some systems, for example, additional credits for years of service

can be claimed based on an employee's unused sick leave at retirement. In recent

years, many governments in California also have granted employees "retroactive

benefits"—that is, increased pension benefits for prior years of service.

In a retroactive benefit situation, an employee might have worked most of his or

her career for a governmental entity under one pension formula, only to benefit

from a significantly larger pension formula put into effect and applied to all

prior years of service just a few years before retirement.

Retiree Health Benefits. Many state and

local governmental entities in California also provide health benefits to

eligible retired employees and/or their spouses, registered domestic partners,

dependents, and survivors of eligible retirees. Generally, public employers

offering such benefits contribute a specific amount toward a retiree's health

premiums each month. The level of these benefits and the eligibility of groups

of retirees to receive the benefits vary considerably among governmental

entities.

Funding Public Employee Retirement Benefits

Funding Pension Benefits. California

governments generally "prefund" the costs of defined pension benefits for their

employees. Through prefunding, public employers and/or employees contribute a

specific percentage of each employee's pay to a public retirement system each

year. In many cases, the percentage paid by the employer and that paid by the

employee is determined through negotiation between governments and unions

representing rank-and-file public employees.

In most cases, the combined employer and employee

contributions are those estimated to be sufficient by the system's

actuaries—when combined with future investment returns of the retirement

system—to cover the portion of future pension benefits earned by that employee

during a given year. This contribution is known as the "normal cost." In making

their estimates, public retirement system actuaries make numerous assumptions

about (1) future investment returns, (2) the longevity of public employees, (3)

the likelihood that an employee will retire in any given year, (4) the

employee's future pay increases, (5) the pension benefits for which the employee

eventually will be eligible, and (6) other factors. To the extent that these

assumptions prove to be incorrect over time, the eventual costs to provide a

given level of benefits will be less or more. In the latter cases, public

employers in California generally are required to provide additional

contributions to fund a given level of pension benefits and pay down what is

called an "unfunded liability."

As of 2007‑08 (the most recent fiscal year for which this

data is available), public employers, on average, made pension contributions

equal to 14.6 percent of employee payroll for non-safety employees and

20.7 percent of employee payroll for safety employees, according to estimates of

the State Controller's Office (SCO). This resulted in $14 billion of employer

contributions to California's public pension systems, including several billion

dollars per year to retire existing unfunded pension liabilities. This amount

probably will increase by billions of dollars per year in the relatively near

future due to new unfunded liabilities resulting mainly from the systems' large

investment losses during 2008.

In addition to contributions made by public employers,

public employees also make contributions to the state's pension systems. The

percentage of payroll contributed by public employees varies. The typical state

employee, for instance, currently make pension contributions equal to somewhere

between about 5 percent and 11 percent of his or her pay. For many state

employees, these employee contributions have increased by several percentage

points of their pay from a few years ago, due mainly to negotiated agreements

between public employee unions and the state.

Funding Retiree Health Benefits. California

governments generally have not prefunded retiree health benefits. This means

that they still generally pay for the costs of these benefits on a

"pay-as-you-go" basis, and there has been relatively little money available from

investment returns to cover the costs of such benefits. Accordingly, each year,

most governments pay for the retiree health benefits consumed during that year

by eligible retirees, dependents, and others. Currently, California governments

are estimated to pay somewhere around $4 billion per year for retiree health

benefits.

Contract Clauses of the U.S. and State Constitutions

Background. Article I, Section 10 of the

U.S. Constitution prohibits any state from passing a "law impairing the

obligation of contracts." As with the constitutions of some other states, the

California Constitution also prohibits the legislative branch of California's

government from passing any law impairing the obligation of contracts. These

clauses are known as the "Contract Clauses" of the U.S. and State Constitutions,

respectively.

Provides Certain Protections Concerning Public

Employee Retirement Benefits. In various instances over the past

century, California governments have made attempts to alter or reduce pension

benefits for current and past employees and to reduce payments to pension

systems. In a number of cases, California courts have held that such actions

violated the Contract Clauses of the U.S. and/or State Constitutions. In a

number of cases, California courts have held that a public employee's pension

constitutes "an element of compensation," that a "vested contractual right to

pension benefits accrues upon acceptance of employment," and that such a pension

right "may not be destroyed, once vested, without impairing a contractual

obligation of the employing public entity." California courts have ruled that

allowable modifications to pension systems for current and past employees, when

they result in a "disadvantage to employees," generally must be accompanied by

"comparable new advantages." For example, a reduction of one part of the benefit

must be accompanied by some other "advantage" to the employee or retiree. The

contractual protections apply to various aspects of the pension benefit and also

have applied to certain commitments of governments to contribute to pension

systems each year. In general, this means that California courts have declared

that it is difficult to modify or alter public employee pension benefits to

reduce governmental costs unless that change is accompanied by comparable new

advantages for affected public employees and retirees.

Municipal Bankruptcy. The U.S. Constitution

also reserves for the U.S. Congress the power to pass uniform laws on the

subject of bankruptcies, which sometimes involve modifications to contracts.

Consistent with this provision of the Constitution, the U.S. Congress has

established one method—bankruptcy—whereby local governmental entities

(but not state governmental entities) can seek to reorganize

(restructure) their contractual obligations. Local governments, however, rarely

seek such bankruptcy protection, and the experience of local governments in

seeking to modify their retirement contracts has been even rarer.

Proposal

Proposed Change to Existing Public Employees' Retirement Benefits

This measure provides that public employee defined

pension benefits in California can only allow for "full retirement ages" of 62

years of age or older. This provision of the measure states that it would apply

to public employees who are employed on the day after this measure is approved

by the state's voters, notwithstanding the Contract Clause of the State

Constitution.

It is unclear to us exactly what "full retirement age"

would be construed to mean in practice. There are at least two possible

interpretations of this provision. One interpretation would prevent "service

retirements" (retirements not related to disability) by current public employees

prior to age 62. (As described above, public employees currently can retire

beginning at age 50, and many groups of public safety employees currently retire

in their early 50s.) A second interpretation would prevent the pension benefits

described earlier from reaching their maximum level until at least age 62. For

example, most state correctional officers currently work under the 3 percent at

50 pension benefit formula. This provision of the measure could be interpreted

as preventing the state from providing a pension benefit to current employees

that reaches this full 3 percent level until at least age 62. In other words, a

smaller benefit factor than the one in the 3 percent at 50 formula might be

allowable for retiring officers between ages 50 and 61. These types of

changes—delaying receipt of pension benefits until later ages—would also affect

the date at which employees would begin to draw any retiree health benefits for

which they are eligible.

Likely to Be Challenged in the Courts. This

measure does not appear to provide a comparable new advantage for existing

employees to offset the possible changes to the retirement age described above.

Accordingly, it is likely that this part of this measure—reducing retirement

benefits for existing public employees—would be challenged in the courts. This

measure states that its various provisions are "severable," meaning that if one

part of the measure is held invalid by the courts, this would not affect the

other parts of the measure that can still be put into effect.

Changes to Future Public Employees' Retirement Benefits

This measure would take effect on the day after it is

approved by a vote of the people. It includes various limitations to retirement

benefits for public employees first hired on and after that date, as follows.

Various Changes to Pension Benefits. For

these future public employees, defined pension benefits would be required to be

limited in the following ways:

-

No "Full Retirement Age" Prior to 62. For

future public employees (as with public employees working on the effective

date of this measure), full retirement ages of less than 62 would not be

permitted. (As noted above, we are unsure how this provision would be

construed in practice.)

-

No Pension Greater Than 60 Percent of Highest

Three Years' Compensation. Defined benefit pensions for future

public employees could be no more than 60 percent of the highest annual

average base wage of the employee over a period of three consecutive years

of employment by a public agency. For future public employees, only base

wages could be included in the calculation of wages used in determining the

pension benefits. Payments received for unused sick leave, for example,

would be excluded from calculations of the annual average base wage.

-

No Pensions for Part-Time Employees and Others.

Future public employees would be prohibited from receiving a defined

benefit pension unless they had been "a full time employee of one or more

public agencies for at least five consecutive years." In the future, certain

public employees who worked on a part-time basis for part or all of their

careers—who may be eligible for defined pension benefits under existing laws

and contracts—might not be eligible under this provision.

-

Future Employee Pension Contributions Must at

Least Equal Employer's. As described above, many public employees

make smaller pension contributions each year than their employers. Under

this measure, future public employees' contributions to pension systems

would be required to be at least equal to those of their employers. This

would tend to increase employees' contributions, thereby reducing employers'

contributions.

All of these limitations would tend to result in

later retirement ages for future public employees. This also would delay the

date at which they begin to draw retiree health benefits for which they are

eligible.

Retroactive Pension Increases Prohibited

This measure provides that public agencies may not

provide retroactive pension benefit increases to "any public agency employee

under any plan."

Retirement Provisions Unaffected by This Measure

This measure states explicitly that it does not affect

the following.

-

Existing Retirees' Benefits. This measure

would not affect benefits of persons who retired from public agency

employment prior to the date this measure takes effect.

-

Death and Disability Benefits. This

constitutional initiative would not limit death or disability benefits for

public employees.

-

Legislators' Retirement Benefits. Under

Proposition 140 (1990), Members of the Legislature elected or serving after

November 1, 1990, are prohibited from receiving pension and retirement

benefits for their legislative service through a state or local retirement

system. (Legislators do, however, participate in the federal Social Security

program.) This constitutional initiative would not alter the limits on

legislative pensions put in place by Proposition 140.

Two-Thirds Legislative Vote Required for Certain Pension Measures

This constitutional initiative allows the Legislature to

enact laws implementing this measure's provisions through bills passed by

two-thirds of the Members of the Assembly and the Senate. Under current law,

some such enactments could be passed with a majority vote of the Assembly and

the Senate.

Fiscal Effects

This measure would result in major changes to how the

state and local governments compensate their employees. The fiscal effects of

these changes would depend in part on how the measure is interpreted by the

courts and the Legislature and implemented by both state and local governmental

entities. Most of the measure's changes would apply only to those public

employees hired after the date it is approved by voters. Accordingly, the full

fiscal effects of this proposal may not emerge until several decades after the

measure's passage—particularly if the courts invalidate the parts of the measure

limiting benefits for existing employees. Below, we discuss how the measure

could affect state and local government costs in the short run (the next few

years) and over the long run (perhaps 20 or more years in the future),

respectively.

Short-Run Fiscal Effects

Possible Significant Reductions if Applied to

Existing Employees. If the measure is allowed by the courts to be

applied to existing employees, it could result in substantial reductions in

state and local government pension contributions beginning almost immediately.

The most substantial decreases could result from lowered state and local pension

contributions related to public safety employees. That is because delaying these

employees' "full retirement age" to 62 or later could result in more savings

than a similar change for teachers and other public employees, who, as shown in

Figure 1, tend to retire fairly close to age 62 already. To the extent that this

measure delayed the retirement date of current employees, governmental payments

for retiree health benefits also would be reduced in the short run.

Because this measure would not affect pension benefits of

those who retire on or before the date it is approved by voters, it could result

in current public employees making choices to retire on or before the Election

Day on which it appears on the ballot in order to avoid having their benefits

reduced. It is impossible to predict exactly how this factor would increase or

decrease governmental costs in the short run.

In Near Future, Relatively Little Savings Related

to Future Employees. The measure would tend to reduce significantly—as a

percentage of payroll—the required employer pension contributions related to

future public employees. This is because the defined benefit pensions for

these employees would be reduced substantially under this measure. In the near

future, however, future public employees subject to all of this measure's

pension limitations would be a relatively small portion of the workforce for

most public agencies. Accordingly, in the short run, savings from reducing

pension benefits for future employees would reduce state and local government

costs by a relatively modest percentage.

Increases in Other Forms of Compensation.

In order to offset the decreased retirement benefits resulting from this

measure, governmental entities likely would increase other forms of compensation

for some employees in order to remain competitive in the labor market. These

other forms of compensation include salaries and contributions to employee

retirement funds other than the defined benefit pension plans addressed by this

measure. (These other retirement funds include "defined contribution" retirement

accounts, for which employers make a specific payment, rather than promise a

specific future benefit.) For some part-time, temporary, and seasonal employees,

this measure's prohibition on enrollment in state or local defined benefit

pension systems would result in new requirements for public employers to make

payments either to the federal Social Security program or an alternative

retirement program, as allowed by federal tax laws and regulations. These

various cost increases would offset the short-term reductions in pension

contributions described above to an unknown extent. The overall magnitude of

these additional costs would be determined by various factors, including labor

market conditions and choices made by governmental entities.

Possible Effects of Pension Fund Cash Flow.

If, as normal costs for public employees decline, policymakers decide to

reduce the combined employer and employee contributions to pension systems, some

public pension systems may receive less cash than they otherwise might on a

monthly and annual basis. Accordingly, these systems may have fewer liquid

assets on hand at any given time to meet their preexisting pension payment

obligations. This could lead some of the systems to reduce the average amount of

time that they invest their assets in the stock, bond, real estate, and other

investment markets. In turn, this may reduce the average annual investment

returns that the systems are able to assume when calculating required normal

cost and other pension payments. If this were to occur, annual pension payments

by governments could increase in the near future. It is impossible to estimate

the magnitude of these costs, particularly since they could vary substantially

from one public pension system to another.

Bottom Line. In the short run, public

employer defined benefit pension contributions would decline by a relatively

modest percentage due to this measure's limitations on pension benefits for

future public employees or perhaps substantially if this measure is allowed by

the courts to limit pensions of existing public employees. These savings would

be offset to an unknown extent by increases in compensation costs for some

public employees, depending on the labor market and future decisions made by

pension systems and other governmental entities.

Long-Run Fiscal Effects

Major Reductions in Government Pension Costs in the

Long Run. Currently, normal cost pension contributions by California

governments to public retirement systems total around $10 billion per year.

State and local governments in California would have substantially smaller

required normal cost contributions for new employees hired after this measure

takes effect. Accordingly, in the long run (after most current governmental

employees retire and most of the state and local government workforce consists

of persons hired after the effective date of this measure), normal cost pension

contributions by California governments would be reduced by billions of dollars

per year (as measured in today's dollars).

Increases in Other Forms of Compensation.

As described above, in order to offset the decreased retirement benefits

resulting from this measure, governmental entities likely would increase other

forms of compensation for some employees in order to remain competitive in the

labor market. These increases would offset the reduced pension contributions

described above to an unknown extent.

Some Additional Flexibility in State and Local

Budgeting Possible. Public employee retirement benefits have a

substantial degree of protection under court decisions and the Contract Clauses

of the U.S. and State Constitutions. Accordingly, state and local government

pension contributions are one of the more inflexible components of public

budgets in California. This measure would reduce pension contributions

substantially over the long run and reduce the possibility that unfunded

liabilities related to pension benefits would consume a significant portion of

future public budgets. For these reasons, the changes included in this measure

could increase budgeting flexibility for state and local governments over the

long run, and this could result in policymakers making different budgetary

decisions, particularly in times of economic and fiscal distress.

Bottom Line. In the long run, public

employer defined benefit pension contributions would decline

substantially—likely by billions of dollars per year (as measured in today's

dollars)—due to this measure's limitations on pension benefits for future public

employees. These savings would be offset to an unknown extent by increases in

compensation costs for some public employees, depending on the labor market and

future decisions made by governmental entities.

Other Fiscal Effects

Variety of Other Fiscal Effects Are Possible.

Particularly over the long run, the measure could result in numerous other

effects on governments. For example:

-

Changes in the types and amounts of public employee

compensation could change the demographics of state and local government

workforces. In particular, public safety employees might be older, on

average. The proportion of public employees who are young (and typically

lower-paid) could be reduced, and the number of retirees drawing retiree

health benefits could be reduced at any given time.

-

Because future governmental workers would be guaranteed

lower annual incomes in retirement, an increased number could enroll in

public social services and health programs and increase those programs'

costs.

These and other factors could affect state and local

government costs and revenues. The net effect of these factors is unknown, but

probably would be less significant than the other fiscal effects discussed in

this analysis.

Fiscal Summary

This measure would have the following major fiscal

effects on the state and local governments:

-

Major reductions in state and local defined benefit

pension contributions—potentially totaling billions of dollars per year (as

measured in today's dollars)—over the long run. These reductions would be

offset to an unknown extent by increases in other compensation costs for

some public employees, depending on labor market conditions and future

decisions made by governmental entities.

Return to Propositions

Return to Legislative Analyst's Office Home Page