Submitted July 15, 2010

Proposition 22

Prohibits the State from Taking Funds Used for Transportation or Local Government Projects and Services. Initiative Constitutional Amendment.

Summary of Legislative Analyst’s Estimate of Net State and Local Government Fiscal Impact

-

Fiscal Impact: Decreased state General Fund spending and/or increased state revenues, probably in the range of $1 billion to several billions of dollars annually. Comparable increases in funding for state and local transportation programs and local redevelopment.

Yes/No Statement

A YES vote on this measure means: The state’s authority to use or redirect state fuel tax and local property tax revenues would be significantly restricted.

A NO vote on this measure means: The state’s current authority over state fuel tax and local property tax revenues would not be affected.

|

Background

Under the State Constitution, state and local government funding and responsibilities are interrelated. Both levels of government share revenues raised by some taxes—such as sales taxes and fuel taxes. Both levels also share the costs for some programs—such as many health and social services programs. While the state does not receive any property tax revenues, it has authority over the distribution of these revenues among local agencies and schools.

Over the years, the state has made decisions that have affected local government revenues and costs in various ways. Some of these decisions have benefited the state fiscally, and others have benefited local governments. For example, in the early 1990s, the state permanently shifted a share of city, county, and special district property tax revenues to schools. These shifts had the effect of reducing local agency resources and reducing state costs for education. Conversely, in the late 1990s, the state changed laws regarding trial court program funding. This change had the effect of shifting local agency costs to the state.

In recent years, the state’s voters have amended the Constitution to limit the state’s authority over local finances. Under Proposition 1A of 2004, the state no longer has the authority to permanently shift city, county, and special district property tax revenues to schools, or take certain other actions that affect local governments. In addition, Proposition 1A of 2006 restricts the state’s ability to borrow state gasoline sales tax revenues. These provisions in the Constitution, however, do not eliminate state authority to temporarily borrow or redirect some city, county, and special district funds. In addition, these propositions do not eliminate the state’s authority to redirect local redevelopment agency revenues. (Redevelopment agencies work on projects to improve blighted urban areas.)

Proposal

As Figure 1 summarizes, this measure reduces or eliminates the state’s authority to:

-

Use state fuel tax revenues to pay debt service on state transportation bonds.

-

Borrow or change the distribution of state fuel tax revenues.

-

Redirect redevelopment agency property taxes to any other local government.

-

Temporarily shift property taxes from cities, counties, and special districts to schools.

-

Use vehicle license fee (VLF) revenues to reimburse local governments for state mandated costs.

As a result, this measure affects resources in the state’s General Fund and transportation funds. The General Fund is the state’s main funding source for schools, universities, prisons, health, and social services programs. Transportation funds are placed in separate accounts and used to pay for state and local transportation programs.

Figure 1

Major Provisions of Proposition 22

|

|

- Restrictions Regarding State Fuel Taxes

|

- Reduces state’s authority to use funds to pay debt service on transportation bonds.

|

- Prohibits borrowing of funds by the state.

|

- Limits state authority to change distribution of funds.

|

- Other Restrictions on the State

|

- Prohibits redirection of redevelopment property tax revenues.

|

- Eliminates state authority to temporarily shift property tax revenues from cities, counties, and special districts.

|

- Prohibits state from using vehicle license fee revenues to pay for state-imposed mandates.

|

|

|

- Repeals state laws enacted after October 20, 2009 if they conflict with the measure.

|

- Provides reimbursement if the state violates any term of the measure.

|

Use of Funds to Pay for Transportation Bonds

State Fuel Taxes. As Figure 2 shows, the state annually collects about $5.9 billion in fuel tax revenues for transportation purposes—with most of this amount coming from a 35.3 cents per gallon excise tax on gasoline. The amounts shown in Figure 2 reflect changes adopted in early 2010. Prior to these changes, the state charged two taxes on gasoline: an 18 cents per gallon excise tax and a sales tax based on the cost of the purchase. Under the changes, the state collects the same amount of total revenues but does not charge a state sales tax on gasoline. (These state fuel tax changes did not affect the local sales tax on gasoline.) Part of the reason the state made these changes is because revenues from the gasoline excise tax can be used more flexibly than sales tax revenues to pay debt service on transportation bonds.

Figure 2

Current State Fuel Tax Revenues for Transportation Purposesa

2010-11

(In Millions)

|

Fuel

|

Excise Tax

|

Sales Tax

|

|

Gasoline

|

$5,100

|

—

|

|

Diesel

|

470

|

$300

|

|

Totals

|

$5,570

|

$300

|

Current Use of Fuel Tax Revenues. The main uses of state fuel tax revenues are (1) constructing and maintaining highways, streets, and roads and (2) funding transit and intercity rail services. In addition, the state uses some of its fuel tax revenues to pay debt-service costs on voter-approved transportation bonds. In the current year, for example, the state will use about $850 million of fuel tax revenues to pay debt-service costs on bonds issued to fund highway, road, and transit projects. In future years, this amount is expected to increase to about $1 billion annually.

Reduces State Authority. The measure reduces state authority to use fuel tax revenues to pay for bonds. Under the measure, the state could not use fuel tax revenues to pay for any bonds that have already been issued. In addition, the state’s authority to use fuel tax revenues to pay for bonds that have not yet been issued would be significantly restricted.

Because of these restrictions, the state would need to pay about $1 billion of annual bond costs from its General Fund rather than from transportation accounts. (In the current year, the amount would be somewhat less because the state would have paid some of its bond costs using fuel tax revenues by the time of the election.) This, in turn, would (1) increase the amount of funds the state would have available to spend for transportation programs and (2) reduce the amount of General Fund resources the state would have available to spend on non-transportation programs.

Borrowing of Fuel Tax Revenues

Current Authority to Borrow. While state fuel tax revenues generally must be used for transportation purposes, the state may use these funds for other purposes under certain circumstances. Specifically:

-

Borrowing for Cash Flow Purposes. The state historically has paid out most of its General Fund expenses between July and December of each year, but received most of its revenues between January and June. To help manage this uneven cash flow, the state often borrows funds from various state accounts, including fuel tax funds, on a temporary basis. The cash flow loans of fuel tax funds often total $1 billion or more.

-

Borrowing for Budget-Balancing Purposes. In cases of severe state fiscal hardship, the state may use fuel tax revenues to help address a budgetary problem. The state must pay these funds back within three years. For example, at the time this analysis was prepared, the proposed 2010–11 state budget included a $650 million loan of state fuel tax revenues to the state General Fund.

Prohibits Borrowing. This measure generally prohibits fuel tax revenues from being loaned—either for cash flow or budget-balancing purposes—to the General Fund or to any other state fund. The state, therefore, would have to take alternative actions to address its short-term borrowing needs. These actions could include borrowing more from private markets, slowing state expenditures to accumulate larger reserves in its accounts, or speeding up the collection of tax revenues. In place of budgetary borrowing, the state would have to take alternative actions to balance future General Fund budgets—such as reducing state spending or increasing state taxes.

Distribution of Fuel Tax Revenues

Current Distribution. Roughly two-thirds of the state’s fuel tax revenues are spent by the state, and the rest is given to cities, counties, and transit districts. Although state law specifies how much money local agencies shall receive, the Legislature may pass a law with a majority vote of each house to change these funding distributions. For example, the state has made various changes to the allocation of transit funding over recent years.

Limits Changes to Distribution. This measure constrains the state’s authority to change the distribution of state fuel tax revenues to local agencies. In the case of fuel excise taxes, the measure requires that the formula to distribute these tax revenues to local governments for the construction or maintenance of local streets and roads be the one that was in effect on June 30, 2009. (At that time, local governments received the revenues generated from 6 cents of the 18 cents being collected from the fuel excise tax.) Under this measure, the state could enact a law to change this allocation, but only by a two-thirds vote of each house of the Legislature and after the California Transportation Commission conducted a series of public hearings.

In the case of diesel sales tax revenues (used primarily for transit and transportation planning), current law requires that the funds be distributed 25 percent to the state and 75 percent to local governments, beginning in 2011–12. The measure specifies that the funds instead be split equally between local and state programs. This change in diesel sales tax revenue distribution, therefore, would provide somewhat lower ongoing funding for local transit purposes and more funding for state transit purposes than otherwise would be the case. Under the measure, the state could not change this distribution of funds.

Allocation of Property Tax Revenues

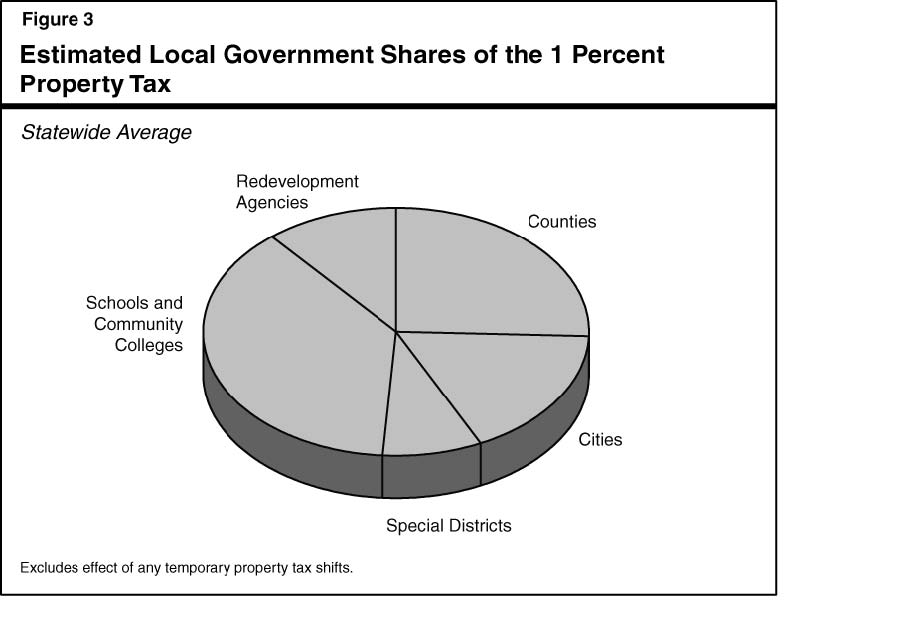

Current Property Tax Distribution. California property owners pay a 1 percent tax on the value of their homes and other properties, plus any additional property tax rates for voter-approved debt. State law specifies how county auditors are to distribute these revenues among local governments. Figure 3 shows the average share of property tax revenues local governments receive.

State law allows the state to make some changes to the distribution of property tax revenues. For example, the state may require redevelopment agencies to shift revenues to nearby schools. Recently, the state required redevelopment agencies to shift $2 billion of revenues to schools over two years. (This amount is roughly 15 percent of total redevelopment revenues.) In addition, during times of severe state fiscal hardship, the state may require that a portion of property tax revenues be temporarily shifted away from cities, counties, and special districts. In this case, however, the state must repay the local agencies for their losses within three years, including interest. Recently, the state required these agencies to shift $1.9 billion of funds to schools. The major reason the state made these revenue shifts was to reduce state General Fund costs for education and other programs.

Reduces State Authority. This measure prohibits the state from enacting new laws that require redevelopment agencies to shift funds to schools or other agencies. The measure also eliminates the state’s authority to shift property taxes temporarily during a severe state fiscal hardship. Under the measure, therefore, the state would have to take other actions to balance its budget in some years—such as reducing state spending or increasing state taxes.

Use of VLF Revenues

Current VLF. California vehicle owners pay a VLF based on their vehicle’s value at a rate of 1.15 percent, including a 0.65 percent ongoing rate and a 0.50 percent temporary rate. Most VLF revenues are distributed to local governments.

Current Mandate Payments. The state generally must reimburse local governments when it “mandates” that they provide a new program or higher level of service. The state usually provides reimbursements through appropriations in the annual budget act or by providing other offsetting funds.

Restricts Use of VLF Funds. This measure specifies that the state may not reimburse local governments for a mandate by giving them an increased share of VLF revenues collected under the ongoing rate. Under the measure, therefore, the state would have to reimburse local governments using other resources.

State Laws That Are in Conflict With This Proposition

Voids Recent Laws. Any law enacted between October 20, 2009 and November 2, 2010 that is in conflict with this proposition would be repealed. Several factors make it difficult to determine the practical effect of this provision. First, parts of this measure would be subject to future interpretation by the courts. Second, in the spring of 2010, the state made significant changes to its fuel tax laws, and the full effect of this measure on these changes is not certain. Finally, at the time this analysis was prepared (early in the summer of 2010), the state was considering many new laws and funding changes to address its major budget difficulties. As a result, it is not possible to determine the full range of state laws that could be affected or repealed by this measure.

Requires Reimbursement for Future Laws. Under this measure, if a court ruled that the state violated a provision of Proposition 22, the State Controller would reimburse the affected local governments or accounts within 30 days. Funds for these reimbursements, including interest, would be taken from the state General Fund and would not require legislative approval.

Fiscal Effects

State General Fund

Effect in 2010–11. This measure would (1) shift some debt-service costs to the state General Fund and (2) prohibit the General Fund from borrowing fuel tax revenues. As a result, the measure would reduce resources available for the state to spend on other programs, probably by about $1 billion in 2010–11. To balance the budget, the state would have to take other actions to raise revenues and/or decrease spending. Overall, the measure’s immediate fiscal effect would equal about 1 percent of total General Fund spending. As noted above, the measure also would repeal laws passed after this analysis was prepared that conflicted with its provisions.

Longer-Term Effect. Limiting the state’s authority to use fuel tax revenues to pay transportation bond costs would increase General Fund costs by about $1 billion annually for the next couple of decades. In addition, the measure’s constraints on state authority to borrow or redirect property tax and redevelopment revenues could result in increased costs or decreased resources available to the General Fund in some years. The total annual fiscal effect from these changes is not possible to determine, but could range from about $1 billion (in most years) to several billion dollars (in some years).

State and Local Transportation Programs and Local Government

The fiscal effect of the measure on transportation programs and local governments largely would be the opposite of its effect on the state’s General Fund. Under the measure, the state would use General Fund revenues—instead of fuel tax revenues—to pay for transportation bonds. This would leave more fuel tax revenues available for state and local transportation programs.

In addition, limiting the state’s authority to redirect revenues likely would result in increased resources being available for redevelopment and state and local transportation programs. Limiting the state’s authority to borrow these revenues likely would also result in more stable revenues being available for local governments and transportation. The magnitude of this fiscal effect is not possible to determine, but could be in the range from about $1 billion (in most years) to several billions of dollars (in some years).

Return to Propositions

Return to Legislative Analyst's Office Home Page