2009-10 Budget Analysis Series: Health

The Legislature enacted the Medi–Cal Long Term Care Reimbursement Act (hereinafter referred to as the “act”), as Chapter 875, Statutes of 2004 (AB 1629, Frommer), with the intent of devising a Medi–Cal long–term care rate–setting methodology that (1) effectively ensures individual access to long–term care services such as skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and (2) promotes quality resident care. The act also established what is termed a quality assurance fee (QAF) that some long–term care providers must pay to the state. The rate–setting methodology and other provisions of the act were to have automatically expired on July 31, 2008, but Chapter 758, Statutes of 2008 (AB 1183, Committee on Budget), extended the so–called “sunset” provision until July 31, 2011.

In this analysis, we provide an overview of the act and how it works, assess its financial effect on the General Fund, discuss problems the state has experienced in collecting QAFs, and recommend steps to address these concerns.

Act Increases Reimbursements for SNFs. The state has about 1,200 long–term care facilities, of which about 1,000 are SNFs, which provide medical, rehabilitative, and skilled nursing care for those who cannot receive such care in a home setting. The act institutes a facility–specific, cost–based, rate–setting methodology for specified classes of SNFs. The new rate–setting methodology replaces a methodology that based rates on average facility costs in geographic regions. The new methodology reimburses facilities for investments they have made in staffing and provides compensation for administrative and capital costs. While, as noted above, the rates set for SNFs are specific to individual facilities, an annual cap limits the amount that rates can be increased on average for all SNFs. Subsequent legislation has adjusted these caps, with the current cap on the average annual rate increase set at 5 percent.

Most California SNFs participating in the Medi–Cal Program are financially better off because of these changes. Under this new rate–setting methodology, between 2005–06 and 2007–08, nursing home rates increased from an average of $142.11 per patient day to $152.48 per patient day, or at an annual average rate of 3.6 percent. In comparison, during this same time period, most other classes of Medi–Cal providers did not receive any rate increases.

Fee Revenues Offset General Fund Costs of Rate Increase. The act imposed a QAF on providers that is intended to offset the General Fund cost increases resulting from the new rate–setting methodology. Federal regulations limit the amount states can charge providers as a QAF to 5.5 percent of a provider’s gross revenues (as defined by federal Medicaid program authorities). This fee mechanism works to benefit the state General Fund.

How QAFs Work. Federal Medicaid law permits states to impose fees on certain health care service providers and in turn repay the providers through increased reimbursements. Because the costs of Medicaid reimbursements to health care providers are split between states and the federal government, this arrangement provides a mechanism by which states can draw down additional federal funds for support of their Medicaid programs. (In California, the Medicaid program is known as Medi–Cal.) These funds can then be used to offset state costs. Our Analysis of the 2004–05 Budget Bill (page C–52) provides a more detailed description of how such a fee mechanism works.

Under federal law, all the providers in a provider class such as SNFs must pay a QAF. Therefore, the QAF must be paid by all SNFs, regardless of whether they benefit from a higher Medi–Cal rate. For more on the different SNF revenue sources, see the box below.

Skilled Nursing Facility Revenues

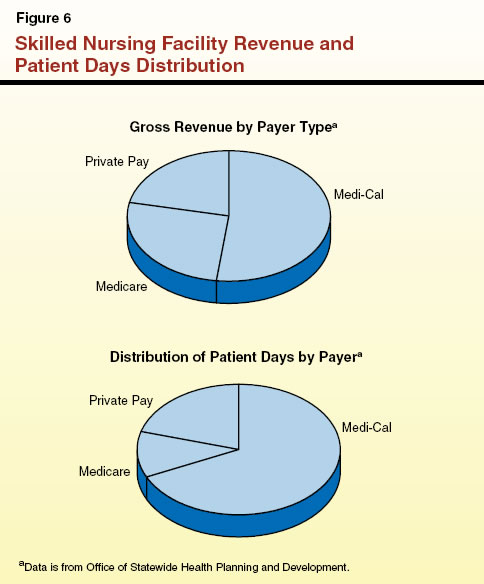

These facilities receive revenues from three main sources:

- Medi–Cal: Medi–Cal pays for the majority of nursing home days in California. These residents must meet Medi–Cal eligibility requirements.

- Medicare: Medicare is a federal health insurance program that provides coverage to eligible beneficiaries at federal expense. However, Medicare provides only a limited nursing home benefit for beneficiaries recovering from a hospital stay. In addition, Medicare generally only pays for 100 days of nursing home care per beneficiary per year.

- Private–pay: Some private–pay nursing home residents pay for care out of their own pocket. Other private–pay residents have their care paid for through long–term care insurance or their existing health care insurance policies.

We display skilled nursing facility revenue and the distribution of patient days in Figure 6.

|

The DHCS, which administers Medi–Cal, calculates each facility’s QAF using a projection of what the facility’s net revenue will be for the annual period beginning August 1 of each year. Each facility must pay 6 percent of their projected net private–pay and Medi–Cal revenue as a QAF. (California excludes Medicare revenues from the fee calculation, which, in part, makes it possible for the fees to remain under the 5.5 percent federal cap mentioned above.) The cost of each facility’s QAF is then reimbursed to the facility in the form of a higher Medi–Cal rate. Facilities with a high percentage of Medi–Cal beds, therefore, generally experience net gains after paying the QAF.

However, the fee does create “winners” and “losers” within the SNF industry depending on the percentage of Medi–Cal beds that a provider operates. For example, a SNF that dedicates 100 percent of its beds to Medi–Cal beneficiaries receives a rate increase for all of its beds. In contrast, a SNF that only serves private–pay and Medicare clients does not receive any rate increase but is still subject to paying the fee.

Nursing Home QAF Interacts With Licensing and Certification Fees. The Licensing and Certification program, located in the Department of Public Health (DPH), is responsible for ensuring that health care facilities comply with state and federal laws and regulations. This program is almost entirely funded through fees imposed on the regulated facilities. The fees used to fund this program count towards the 5.5 percent federal cap. Currently, the total combined amount collected under the QAF and by the Licensing and Certification program does not reach the federal cap.

What Financial Effect Has the Act Had on the General Fund?

Below, we examine the act’s effect on the General Fund and also examine ways in which the original legislation might be amended to better benefit the General Fund.

General Fund Will Benefit Less in Future Years. The rate–setting methodology adopted under the act has resulted in increased rates for SNFs and, therefore, additional state costs. At present, these increased state costs are being more than offset by QAF revenues. However, the General Fund offset provided by the fees is likely to erode over time. This is primarily because the revenues upon which the QAF is based grow at a slower pace than the costs of the projected rate increases permitted under the act. Under the long–term care rate–setting methodology, the costs experienced by nursing homes are the basis for their annual rate increases. Our analysis indicates that, in the future, revenue generated by QAF will not be enough to offset the higher General Fund costs associated with the rate increases that have resulted from the new rate–setting methodology. The current provisions of the act, if not changed by the Legislature, could result in a net loss to the General Fund, potentially in the low tens of millions of dollars annually, beginning in 2010–11.

Some Revenue Is Exempted From the QAF. As noted earlier, DHCS exempts a SNF’s Medicare revenue from their calculation of net revenue, which lowers the total amount of QAF collected. This arrangement benefits facilities that have a high proportion of patients that are paid for through Medicare because these facilities pay a smaller QAF. This exclusion of Medicare revenue from the state’s calculation of net revenue reduces the QAF revenues significantly. Based upon projections of Medicare revenue for the 2008–09 budget year, the state is foregoing imposing a QAF on approximately $1.7 billion dollars of revenue. This exclusion of Medicare revenues is costing the state approximately $26 million General Fund in the budget year.

Some Facilities Fail to Pay the QAF

Despite the exclusion of Medicare revenue from the QAF, about 10 percent of facilities had initially failed to pay the fees they owed for 2006–07. (This percentage is likely to drop as further collections occur.) The SNFs that are delinquent in paying the fees are generally those with patient populations that are mostly Medicare or private–pay patients. In large part, this is because these facilities benefit little from the higher Medi–Cal reimbursement rate, since they likely are taking few, if any, patients with Medi–Cal.

At the time this analysis was prepared, facilities collectively owed over $71 million to the General Fund for the two–year period ending with 2006–07. Although repayment agreements have been reached to recover part of these monies, no repayment agreement is in effect for almost $30 million of the delinquent amounts. A larger amount ($100 million) is still owed for fiscal year 2007–08, but according to DHCS much of this amount has only recently become due and thus is likely to eventually be paid by SNFs.

DHCS Has Three Options to Address Nonpayment. The DHCS has some recourse under current law if the operator of a facility chooses not to pay the QAF. If a facility with Medi–Cal beds does not pay the fine, DHCS can institute a payment withhold from future Medi–Cal payments to collect the amount owed. However, this approach does not work with facilities that do not have Medi–Cal beds.

In these cases, DHCS can institute a financial penalty for late payment or nonpayment of the QAF. The act mandates that the fine be equal to 50 percent of a facility’s unpaid fee. At the time this analysis was prepared, DHCS had not imposed such a fine upon any facilities, although it has notified some facilities that they may find themselves subject to a fine if they continue nonpayment.

The fine structure is problematic for the following reasons:

- If the fine amount is large, it could affect the facility’s cash flow to the extent that it impairs the facility’s ability to operate, potentially putting at risk the health care of the residents.

- The imposition of a large fine may discourage a facility from accepting Medi–Cal patients because, if it later did so, DHCS would likely withhold payments in order to recover the fees that were owed. This would be contrary to the state’s long–term interest in having a large number of providers willing to accept Medi–Cal patients.

As a last recourse, DHCS can work with the DPH’s Licensing and Certification division to revoke or delay issuance of the renewal of a facility’s license. At the time this analysis was prepared, no facility had lost its license or had the renewal of its license delayed because of failure to pay the QAF. The DPH has indicated its reluctance to revoke or delay renewal of a facility’s license as a punitive measure on the grounds that such a revocation may create instability in the nursing home industry. According to DPH, the expenses and disruption of service involved with a facility’s loss of license often means a facility will close and be unable to reopen.

Analyst Recommendations: Expand Fee and Adopt More Effective Enforcement Mechanisms

Realign Rates and QAF to Ensure Continued Cost Avoidance. When the rate–setting methodology and the QAF sunset at the end of 2010–11, we recommend that the Legislature reexamine the provisions of the act and its costs and benefit to the General Fund. At that time, the Legislature should specifically consider whether QAF revenues remain sufficient to offset General Fund costs that are driven by the rate–setting mechanism established under the act. The Legislature should also consider at that time whether the various provisions of the act have continued to meet its original legislative intent.

Restructure Waiver Agreement to Include Medicare Revenue. We recommend that DHCS be directed to include Medicare revenue in its calculation of revenues owed under the QAF. This would potentially result in a $26 million per year benefit to the state General Fund.

Create a More Effective Enforcement Mechanism to Collect Overdue Fees. We recommend that the Legislature amend the act to provide more effective enforcement mechanisms for nonpayment of the QAF. Specifically, we recommend that the Legislature create a sliding–scale of fines in lieu of the currently required fine of 50 percent of the amounts owed. Initially imposing a more modest fine, perhaps 10 percent of the amount owed, and escalating the fine over time as the QAF remained unpaid, would probably result in a more effective enforcement mechanism that resulted in timely payments of these fees. The fiscal effect of our proposed change in collection enforcement procedures is unknown. If it resulted in a 10 percent increase in revenues, as much as $10 million in additional fees would be collected annually.

Return to Health Table of Contents, 2009-10 Budget Analysis SeriesReturn to Full Table of Contents, 2009-10 Budget Analysis Series