The Department of Mental Health (DMH) directs and coordinates statewide efforts for the treatment of mental disabilities. The department’s primary responsibilities are to (1) provide for the delivery of mental health services through a state–county partnership, (2) operate five state hospitals, (3) manage state prison treatment services at the California Medical Facility at Vacaville and at Salinas Valley State Prison, and (4) administer various community programs directed at specific populations.

The state hospitals provide inpatient treatment services for mentally disabled county clients, judicially committed clients, clients civilly committed as sexually violent predators (SVPs), mentally disordered offenders, and mentally disabled clients transferred from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

Budget Proposal Increases DMH’s Overall Budget. The budget proposes $5 billion from all fund sources for support of DMH programs in 2008–09, an increase of $144.4 million, or 3 percent, above the revised estimate of current–year expenditures. The proposal includes about $2.1 billion General Fund, which is an increase of $143.8 million General Fund, or 7.4 percent, from the revised current–year budget. The major spending proposals are discussed below.

State Mental Hospitals/Long–Term Care Services. The Governor’s spending plan proposes $1.3 billion ($1.2 billion General Fund) in 2008–09, an increase of $78.6 million ($78 million General Fund) from the adjusted 2007–08 budget. The Governor’s budget exempts state hospitals and related programs from across–the–board reductions because of the risk to public safety by releasing dangerous individuals.

The proposed increase is due primarily to employee compensation adjustments required by the Coleman court, the continued activation of Coalinga State Hospital, and compliance with the Civil Rights for Institutionalized Persons Act (CRIPA) consent decree requirements. Additionally, the Governor has proposed about $3 million General Fund for SVP evaluations for full implementation of Proposition 83, also known as Jessica’s Law, and Chapter 337, Statutes of 2006 (SB 1128, Alquist). The increase also includes $1.8 million General Fund for a 4 percent increase for clinical care costs and the expected participation of four SVPs in the Conditional Release Program. We discuss proposals affecting the state hospital system and SVPs in more detail below.

Community Services Budget Proposal. The Governor’s spending plan proposes $3.7 billion from all funds ($884.7 million General Fund) for support of the community services programs, an increase of $65.9 million General Fund compared to the revised 2007–08 budget.

The community services budget plan includes the following proposals:

- Funding for Mental Health Services to Special Education Pupils (AB 3632). The budget proposes a $52 million General Fund increase to fund prior–year obligations for mental health services provided to children enrolled in special education as directed under the AB 3632 mandate and as required by the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

- Increased Early and Periodic Screening Diagnosis and Treatment (EPSDT) Program Funding. The Governor’s spending plan proposes $924 million ($455.5 million General Fund) for support of EPSDT services, a net increase of 2.9 percent, or $11.8 million, over current–year revised estimates due to increases in caseload, utilization, and costs of services as well as adjustments to Mental Health Services Act (MHSA)–EPSDT related services. The net increase incorporates the Governor’s 10 percent budget–balancing reductions totaling $6.7 million General Fund in the current year and $46.3 million General Fund in the budget year. The Governor’s budget–balancing reductions are achieved through proposals to: (1) impose a prior authorization requirement on all requests for EPSDT day treatment services that exceed six months, (2) eliminate the annual cost–of–living adjustment (COLA) increase to provider rates, and (3) reduce the non–inpatient provider rates by 5 percent.

- Healthy Families Funding Net Increase. The budget proposes $31.1 million ($640,000 General Fund), an increase of $6 million ($134,000 General Fund) to provide supplemental mental health services to children enrolled in the Healthy Families program. The net increase includes the effect of the 10 percent budget–balancing reductions.

- Reduced Mental Health Managed Care Provider Rates. The budget plan proposes a total of $421.5 million ($214.4 million General Fund) for 2008–09, a decrease of $22.6 million ($11.6 million General Fund) over the current year mostly due to elimination of an annual COLA and other rate reductions.

- Early Mental Health Initiative Program Reduction. The budget plan proposes about a 10 percent reduction or $1.6 million General Fund in 2008–09 for mental health intervention and prevention services for children in grades K–3.

- Implementation of Foster Children Specialty Mental Health Services. The Governor’s spending plan proposes $188,000 ($94,000 General Fund) for implementation of Chapter 469, Statutes of 2007 (SB 785, Alquist), to provide foster children with specialty mental health services.

Updated caseload data indicate that the amount of General Fund support needed for the state hospital system is likely to be overstated in both the current and budget year. We recommend the Legislature recognize current–year savings of $12.6 million and budget–year savings of $13.8 million General Fund to adjust for overbudgeting of the sexually violent predator caseload. (Reduce Item 4440–011–0001 by $12.6 million in the current year and $13.8 million in the budget year.)

New SVP Laws Increase Demands on Department Resources. Chapter 337 was approved by the Legislature and signed by the Governor in September 2006. Chapter 337 made changes in law that generally increase criminal penalties for sex offenses and strengthen state oversight of sex offenders. Additionally, the voters in the November 2006 statewide election approved Proposition 83. This measure increases penalties for violent and habitual sex offenders and expands the definition for a SVP commitment.

State hospitals, operated by DMH, hold sex offenders who have been committed as SVPs. State mental hospitals also hold some sex offenders who have completed their prison sentences, but are still undergoing SVP evaluations for commitment proceedings. The new SVP laws have increased the demands on the department by requiring increased screenings and evaluations. (For additional background, see

page C–99 of the Analysis of the 2007–08 Budget Bill.)

Governor’s State Hospital Budget Proposal. The Governor’s spending plan for state hospitals proposes $1.2 billion (nearly all General Fund) in 2008–09, an increase of $79.4 million ($78.8 million General Fund) from the adjusted 2007–08 budget. The proposed increase is due primarily to a projected increase in SVP caseload, continued activation of Coalinga State Hospital, and compliance with CRIPA consent decree requirements.

SVP Caseload Likely to Be Below Projected Level. At the end of January 2008, the total SVP caseload was 689, an increase of 38 SVPs during the first seven months of 2007–08. The department estimates that the number of SVPs in state hospitals will approach 867 patients by the end of the current year, an increase of 178 patients, or about 26 percent above the caseload as of January 2008. Additionally, the department estimates that the SVP population will reach 1,227 patients by the end of the budget year, an increase of 360 patients.

Given that the SVP population in the past seven months grew by 38 patients, it seems unlikely that in the next five months the caseload will grow by 178 patients and that the caseload will increase by another 360 patients in the budget year. Based on our analysis, we believe that it is more likely that the SVP caseload will grow by as much as 50 SVPs in the remaining five months of the current year and 220 in the budget year.

Analyst’s Recommendation. We recommend that the Legislature recognize General Fund savings of $12.6 million in the current year and $13.8 million in the budget year to adjust for overbudgeting of the SVP caseload.

Our analysis of the Medi–Cal caseload shows that the Governor’s mental health managed care budget proposal is likely overstated in the budget year. Based on a reduction of 172,000 eligible mental health managed care beneficiaries, we recommend a corresponding reduction of $2.5 million in the budget year. We will monitor caseload trends and recommend any needed adjustments at the May Revision. (Reduce Item 4440–103–0001 by $2.5 million.)

Administration’s Caseload Projections. The budget projects an overall increase in the mental health managed care caseload, including psychiatric inpatient services, and requests about $3.5 million General Fund for this caseload growth. Specifically, the DMH projects an increase of about 98,100, or 1.5 percent, in Medi–Cal eligibles for psychiatric inpatient services.

Medi–Cal Caseload Declining in the Budget Year. The Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) operates the Medi–Cal Program and estimates the program’s caseload. Several other departments use this information for their caseload projections. Our analysis indicates that DMH’s estimate of the number of Medi–Cal beneficiaries using mental health managed care services is inconsistent with DHCS’ estimate.

The DHCS projects that the overall Medi–Cal caseload will decline in the budget year, generally due to budget–balancing reductions that tighten eligibility restrictions. In particular, the DHCS projects a reduction of 73,900 beneficiaries for Medi–Cal mental health services, or 1.1 percent, in the budget year compared to the current year. On the other hand, DMH projects an increase in these beneficiaries of 98,000. Thus, compared to DHCS estimates, it appears that DMH overstated its caseload by 172,000 individuals, or about 2.6 percent. This caseload discrepancy may be explained by DMH excluding overall Medi–Cal eligibility budget–balancing reductions in its estimates.

Analyst’s Recommendation. The DMH mental health managed care caseload projection is likely overstated in the budget year and is inconsistent with Medi–Cal caseload data available at this time. Based on a reduction of 172,000 eligible beneficiaries, we recommend a corresponding reduction of $2.5 million to mental health managed care in the budget year. More updated caseload information will be available at the May Revision, at which time the Legislature can assess the level of funding proposed for mental health managed care services. We will continue to monitor Medi–Cal caseload trends related to mental health managed care and recommend appropriate adjustments to the budget estimate at the May Revision.

The cost of mental health drugs in the Medi–Cal Program continues to grow. We estimate the state can save about $5 million General Fund annually by reducing inappropriate prescribing practices. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature consider the following two options: (1) encourage county participation in the California Mental Health Care Management (CalMEND) Program and (2) expand the use of fixed annual allocations to counties that include the cost of prescription drugs. We further recommend the Legislature approve the Governor’s CalMEND proposal to support three limited–term positions and expand program activities.

Who Provides Mental Health Services? The DMH directs and coordinates statewide efforts for the treatment of mental health disabilities. The DMH, in some cases, only provides part of the services that beneficiaries receive to address their mental health needs. For example, some individuals are dually diagnosed as being mentally ill and having a drug dependency problem or as being mentally ill and being developmentally disabled. In the case of a dual diagnosis, a beneficiary may also access programs managed by, for example, the Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs and the Department of Developmental Services. Services for mental health problems often include a combination of counseling and therapeutic medications.

There is a difference between who provides specialty mental health services and general mental health care needs. For example, a psychiatrist usually treats individuals with severe mental health problems such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. In contrast, a general medical practitioner can treat patients who have less severe mental health problems such as mild depression. The Medi–Cal Program provides general mental health care services for Medi–Cal beneficiaries. Specialty mental health services are “carved out” from general Medi–Cal services and are provided by specialists in county Mental Health Plans (MHPs).

The cost of prescription drugs provided to Medi–Cal beneficiaries receiving specialty mental health services are not paid through MHPs. Instead, the Medi–Cal Program pays on a fee–for–service basis for drugs prescribed through MHPs to Medi–Cal beneficiaries. The exception to this is a pilot program in San Mateo County that includes the costs of mental health drugs and related laboratory services. Specifically, the state pays an additional fixed annual allocation to cover these expenses.

Significant Growth in Medi–Cal Spending for Mental Health Drugs. State spending for all prescription drugs in the Medi–Cal Program grew by about $1.9 billion General Fund, or 336 percent, between 1994–95 and 2004–05. (Drug costs cited in this analysis do not include state or federal drug rebates because this information is proprietary.) Of this increase, $535 million General Fund, or nearly 30 percent, was due to increased spending on mental health drugs. The average annual growth rate of mental health drug expenditures during this ten–year period was about 25 percent. Our analysis does not include data from the more recent years because implementation of the federal drug benefit known as Medicare Part D distorts the data. See text box for more information about Medicare Part D impacts.

Medicare Part D Reduces State Drug Costs. The federal Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act provides a Medicare drug benefit component, known as Part D, that went into effect January 1, 2006. Prior to Medicare Part D, individuals who are entitled to Medicare benefits and who are also eligible for some form of Medi–Cal benefit received most of their prescription drugs through Medi–Cal. Since the implementation of Medicare Part D, these individuals now receive most of their prescription drugs through the Medicare Program. As a result, Medicare Part D now covers about one–half of the previous Medi–Cal mental health prescription drug volume according to Department of Health Care Services.

Antipsychotic Medications are Generally the Most Expensive. Antipsychotic medications are generally the most costly mental health drugs paid for by Medi–Cal and are primarily used by psychiatrists to treat patients suffering from schizophrenia. State spending on antipsychotic medications accounts for over one–half of the cost of all mental health fee–for–service prescription drugs in the Medi–Cal Program. The average monthly cost for an antipsychotic prescription was about $319 in 2006–07. This amounts to an average annual total drug cost of $3,828 per person. In contrast, the average cost for a monthly prescription for an antidepressant was $79, or $948 annually in 2006–07.

Polypharmacy generally refers to the use of multiple medications of the same type by a patient. According to the academic health literature, polypharmacy use involving antipsychotic medications is particularly common. In some cases, polypharmacy can be appropriate for antipsychotic medications. For example, clinical guidelines recommend polypharmacy for a short duration (not more than two months) when switching or transitioning from one antipsychotic to another. Clinical guidelines generally do not support the use of two or more antipsychotic drugs beyond these transition periods and, therefore, experts consider polypharmacy beyond two months inappropriate. Additionally, the costs of polypharmacy can be twice as much as treatment with one medication. Nonetheless, polypharmacy, while appropriate in some situations, can in other situations result in unnecessary costs and potentially harmful side effects.

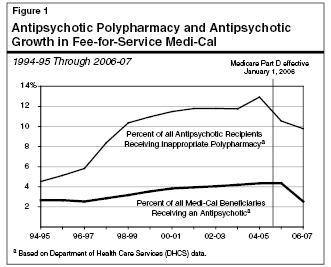

As shown in Figure 1, based on DHCS data, the prevalence of inappropriate polypharmacy among Medi–Cal beneficiaries receiving an antipsychotic medication grew significantly in the decade prior to 2005–06, peaking at about 13 percent between 2004–05 and 2005–06. In 2006–07, the most recent year data are available, nearly 10 percent of Medi–Cal beneficiaries taking an antipsychotic were polypharmacy patients. This is a slightly reduced prevalence rate compared to prior years, mostly due to the impact of Medicare Part D. The risks of such prescribing practices are increased costs to the state and potentially negative impacts on the health of the person taking the drugs.

There are a couple of efforts underway in California which may help control the rising cost of mental health drugs in the Medi–Cal Program.

Overview. The 2006–07 Budget Act appropriated initial funding for the California Mental Health Care Management (CalMEND) program in an effort to address rising drug costs and a lack of coordination in California’s mental health delivery system. The CalMEND program is an interdepartmental, coordinated effort to help improve the cost–effectiveness of providing community mental health services in California. The program consists of multiple agencies, including DHCS, DMH, county MHPs, other state departments, and contracted entities.

The CalMEND began its efforts with a project directed at reducing the use of inappropriate polypharmacy for antipsychotic medications. In 2007–08, participating counties are implementing various best practices to decrease inappropriate antipsychotic prescribing. One of these practices is the use of medication algorithms which provide a “decision making tree” model that helps a health care practitioner determine the best drug course for a patient. These algorithms also include educational components and clinical assessment tools. At least five counties including Orange, Alameda, Fresno, Marin, and Stanislaus have been participating during the current year and results of the initial implementation efforts, including savings associated with this pilot, will be available within the next six months. A variety of other pilots and outreach projects are also in development or are underway such as the creation of standardized pharmacy utilization reports to promote quality improvement and a pilot for medication management therapy using pharmacists to better manage medications.

Governor’s Budget Increases Spending for CalMEND. The CalMEND program is funded by matching MHSA funds with federal funds obtained through the Medi–Cal Program. (Voters in the November 2004 election approved MHSA, or Proposition 63, which imposes an additional 1 percent rate on the portion of incomes in excess of $1 million, for a total marginal rate of 10.3 percent for affected taxpayers.) For 2008–09, the Governor’s spending plan proposes $1.4 million, an increase of $421,000 above the current year, for CalMEND. The DHCS, along with other partners, primarily intends to use these additional funds to implement and expand various pilots, including the project targeting inappropriate antipsychotic use. Additionally, the funding will be used for increased data evaluation and to provide three limited–term positions for Medi–Cal’s Pharmacy Benefits Division for maintenance and management of the program.

San Mateo County’s Program. The San Mateo MHP, unlike other counties, receives what is effectively a capitated rate from DMH for the provision of all mental health services, including prescription drugs. Essentially, the cost of mental health prescription drugs is “carved into” the county’s allocation. By “carving in” the cost of prescription drugs into the county’s allocation it provides the county an incentive to aggressively manage drug costs in order to ensure that the funds it receives are adequate to cover the cost of care for all services.

Evaluation Due in March 2008. The program has been operating for more than ten years under the assumption that it was cost–effective; however, no formal evaluation of its cost–effectiveness has been completed. An evaluation of the program’s cost–effectiveness is due to the Legislature in March 2008 as required by Chapter 188, Statutes of 2007 (AB 203, Committee on Budget). Specifically, this report will: (1) articulate best practices learned from the San Mateo program and whether these best practices should be replicated statewide, (2) offer suggestions to improve the program, and (3) clarify the program’s relationship to other local and statewide efforts related to pharmaceutical usage and purchasing, such as those conducted through the Health Plan of San Mateo and the CalMEND project, as well as others.

Potential Savings Based on Improved Care Management. The state may be able to achieve a greater level of savings for the cost of mental health drugs by encouraging county mental health plans to adopt strategies that help to ensure they use the most appropriate clinical practices such as those supported by CalMEND. Specifically, county participation in CalMEND could help reduce the rate of inappropriate polypharmacy. Based on our review of polypharmacy trends, we estimate prescription drug costs in the Medi–Cal Program could be reduced by about $5 million General Fund annually depending on the length and overall reduction rates of antipsychotic polypharmacy.

One option to encourage more counties to participate in CalMEND would be to create a “set aside” award for counties. This set aside for counties could be a direct share of the savings to the state or a financial incentive from other fund sources such as MHSA monies. This additional incentive could help accelerate county implementation of clinical best practices that are likely to improve care and coordination while also reducing costs.

Analyst’s Recommendation. Given the potential for savings, we recommend the Legislature consider options to encourage county participation in CalMEND. We also recommend the Legislature consider expanding, for county MHPs, the use of fixed allocations that include the cost of prescription drugs. The Legislature will be further informed on this issue when the results from an evaluation of the state’s only model for such an approach are available in March 2008. Finally, we recommend approval of the Governor’s CalMEND proposal to support three–limited term positions and expand the program’s pilot activities.

Return to Health and Social Services Table of Contents, 2008-09 Budget AnalysisReturn to Full Table of Contents, 2008-09 Budget Analysis