Total expenditures for the regional center system that provides services for persons with developmental disabilities more than doubled between 1999–00 and 2009–10, leading to a series of actions by the Legislature to slow down the growth in the program. In this report, we describe and assess proposals in the Governor’s 2011–12 budget plan to achieve further cost containment in programs administered by the Department of Developmental Services (DDS), including community services. We also provide the Legislature with additional options to achieve savings in community services through expansion of the existing Family Cost Participation Program (FCPP) or through implementation of “means testing” to determine program eligibility. Either of the approaches that we recommend would help ensure the long–term sustainability of the program for those consumers with the greatest financial need for its services.

Developmental disabilities include, but are not limited to, mental retardation, cerebral palsy, autism, and disabling conditions closely related to mental retardation. The Lanterman Developmental Disabilities Services Act of 1969 forms the basis of the state’s commitment to provide developmentally disabled individuals with a variety of services, which are overseen by DDS. Unlike most other public social services or medical services programs, services are generally provided to the developmentally disabled without any requirements that recipients demonstrate that they or their families do not have the financial means to pay for the services themselves.

The Lanterman Act establishes the state’s responsibility for ensuring that persons with developmental disabilities, regardless of age, have access to services that sufficiently meet their needs and goals in the least restrictive setting. Individuals with developmental disabilities have a number of residential options. Slightly more than 99 percent receive community–based services and live with their parents or other relatives, either in their own houses or apartments, or in group homes or Intermediate Care Facilities that are designed to meet their medical and behavioral needs. Slightly less than 1 percent live in state–operated, 24–hour facilities (described in the next section).

Developmental Centers (DC) Program. The DDS operates four DCs and one smaller leased facility which provide 24–hour care and supervision to almost 2,000 consumers. All the facilities provide residential and day programs as well as health care and assistance with daily activities, training, education, and employment. The department is in the process of closing Lanterman DC and shifting its clients into community placements and to other DCs.

Community Services Program. The state provides community–based services to clients through 21 nonprofit corporations known as regional centers (RCs), that are located throughout the state. The RCs are responsible for eligibility determinations and client assessment, the development of an individual program plan (IPP), and case management. They generally only pay for services if an individual does not have private insurance or they cannot refer an individual to so–called “generic” services that are provided at the local level by counties, cities, school districts, or other agencies. As the payer of last resort, the RCs purchase services from vendors for more than 244,000 consumers. These services include day programs, transportation, residential care provided by community care facilities, and support services that assist individuals to live in the community. The RCs purchase more than 100 different services on behalf of consumers.

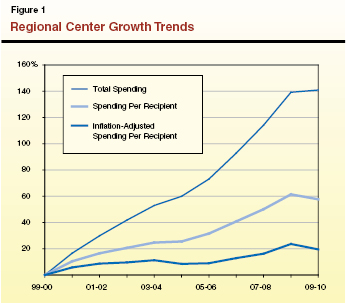

Between 1999–00 and 2009–10, total expenditures for the RC program more than doubled. The increase in costs is attributable to several factors. New medical technology, treatments, and equipment have broadened the scope of services available to the developmentally disabled. Other factors include increased life expectancy of RC consumers, increased diagnosis of autism, and the comparatively higher costs of treating autism.

As shown in Figure 1, between 1999–00 and 2009–10, total spending for RC operations and purchases of services grew by 145 percent. Average per person spending went up by 58 percent. Adjusted for inflation, per person spending went up 20 percent.

The real increases in spending for the community service program described above occurred even though the Legislature has taken a number of significant actions that have reduced current RC costs by more than $500 million annually. Among the major cost–containment measures that have been put in place:

- Rate Freezes for Certain Programs. In recent years, the Legislature has achieved savings on RC purchases of services by freezing rates for day programs, work activity programs, in–home respite, community care facilities, habilitation services, and other services for which the RCs negotiate contracts.

- Provider Payment Reductions. The 2010–11 spending plan included a broadly imposed 4.25 percent reduction in payments to providers. This 4.25 percent reduction has also been applied to RC operations. Absent legislative action, these reductions will end after 2010–11.

- Savings Developed through a Workgroup Process. The 2009–10 spending plan included a package of General Fund savings proposals that DDS developed mainly by working with various stakeholder groups. The options to achieve savings generally make more efficient use of existing resources. For example, one proposal maximizes the use of public transportation for consumers instead of purchasing transportation. Another action expanded the use of neighborhood preschools in lieu of obtaining other more costly services for children.

- Parental Cost Participation Program Established. The FCPP, established in 2004–05, requires that families with children between 3 and 18 years of age and incomes over 400 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), pay a share of the cost for certain services included in their child’s IPP. The FCPP was expanded in 2008–09 to achieve additional savings.

- Maximizing Use of Federal Funds. In recent years, DDS has successfully implemented several proposals to maximize the amount of federal funds available to support the RC program. For example, in the past, the department has undertaken initiatives to maximize the number of consumers enrolled under the Home and Community Based Services Waiver, thereby drawing down federal matching funds that can be used in lieu of General Fund to provide services to RC consumers.

- Use of Alternative Sources of State Funding. Proposition 10, an initiative approved by the voters in November 1998, enacted a 50–cent per pack increase in tobacco taxes and devoted the monies to early childhood education programs administered by a state and county commissions. The 2010–11 budget relied on a voluntary $50 million contribution of funding to support community services for children that was used in lieu of General Fund support for the program.

- Other Programmatic Changes. Recent spending plans have achieved General Fund savings through various other programmatic changes, such as allowing RCs to conduct intake and assessment of consumers within 120 days rather than requiring that this process be completed within 60 days. In order to reduce community program costs, the RC caseloads handled by workers were increased.

The budget proposes $4.5 billion (all funds) for support of DDS programs in 2011–12, which is 6.6 percent below the revised estimate of current–year expenditures. General Fund expenditures for 2011–12 are proposed at $2.4 billion—a decrease of $110 million, or 4.4 percent, below the revised estimate of current–year expenditures.

DC Budget Proposal. The budget proposes $618 million from all funds (including $324 million from the General Fund) for the support of DCs in 2011–12. This represents a net increase of $41 million General Fund, almost 15 percent above the revised estimate of current–year expenditures. This is mainly due to the expiration of a temporary increase in the rate at which the state received federal matching funds for services for DC residents. The loss of these federal funds is backfilled under the Governor’s budget proposal with state General Fund support.

Community Services Budget Proposal. The Governor proposes $3.8 billion from all funds, ($2 billion General Fund) for the support of the community services program in 2011–12. This represents a $153 million General Fund decrease, or 7 percent, below the revised estimate of current–year spending. The decrease is a net result of caseload growth, changes in federal funding levels, and budget reductions proposed by the Governor.

Expenditure Reductions and Cost Containment. Figure 2 summarizes the Governor’s major proposals to achieve a total of $750 million in General Fund savings in DDS programs. Of this total amount of savings, the administration proposes to achieve $217 million General Fund savings through these specific actions:

Figure 2

2011–12 Savings Proposals for the Department of Developmental Services

(In Millions)

|

|

General Fund

|

Other Funds

|

|

Alternative Funding

|

|

|

|

Federal certification of Porterville Developmental Center

|

–$10.0

|

$10.0

|

|

Additional federal financial participation under the 1915(i) SPA

|

–60.0

|

60.0

|

|

Continuation of Proposition 10 funding

|

–50.0

|

50.0

|

|

Federal Money Follows the Person Grant

|

–5.0

|

5.0

|

|

Subtotals

|

(–$125.0)

|

($125.0)

|

|

Expenditure Reductions and Cost Containment

|

|

|

|

4.25 percent payment reduction to regional center (RC) operations

|

–$15.5

|

–$7.2

|

|

4.25 percent payment reduction to RC providers

|

–76.0

|

–66.9

|

|

Undetermined expenditure reductions and cost containment

|

–533.5

|

Undetermined

|

|

Subtotals

|

(–$625.0)

|

(–$74.1)

|

|

Total Savings

|

–$750.0

|

$50.9

|

|

|

|

- Continue Provider Payment Reductions. The administration proposes to achieve $91.5 million in General Fund savings through a one–year extension of the temporary 4.25 percent reduction to provider payments ($76 million) and RC operations ($15.5 million).

- Further Increase Federal Funding. The administration proposes to achieve $75 million in General Fund savings by increasing federal funds through three separate initiatives. Most of the increased federal funds ($60 million) would be achieved by amending the state Medicaid plan to allow for the inclusion of additional consumers and related expenditures.

- Continue to Use Proposition 10 Funding. The administration proposes to continue to use $50 million in Proposition 10 funds in lieu of General Fund to provide RC services to children up to six years of age.

The administration proposes to achieve an additional $533.5 million in General Fund savings through a variety of mechanisms—including DC expenditure reductions, increased accountability and transparency, and implementation of statewide service standards. However, at the time this analysis was prepared, the administration had not identified the specific actions within this broad category that would be used to reduce expenditures, the specific savings associated with each such measure, or the proposed statutory changes that would be needed to carry out such changes.

Governor’s Approach Has Merit, but Lacks Detail. Overall, we find that the Governor’s budget proposal has merit. Some of the proposals are identical to ones that the Legislature has approved before. However, the proposed reduction of $533 million through increased accountability and transparency and implementation of statewide service standards ventures into new territory. The department, however, has not yet documented how this estimated level of savings would be achieved from these measures. Consequently, the Legislature does not have the information it needs to determine whether the administration’s proposal would actually achieve the level of savings that are claimed.

At the time this analysis was prepared, the department had initiated outreach to providers, advocates, stakeholders, and consumers through a survey process. Specifically, the department’s survey is intended to ask for ideas on how to impose statewide service standards in eight areas: (1) behavioral services; (2) day programs, supported employment, and work activity program services; (3) Early Start services for children up to age three; (4) health care and therapeutic services; (5) independent living and supported living services; (6) residential services; (7) respite and other family services; and (8) transportation services.

In addition to the actions proposed by the administration in the 2011–12 budget plan, the Legislature may wish to consider two additional options for achieving savings in the community services program: expansion of the existing FCPP and so–called means testing of the community services program.

As described above, the Legislature established the FCPP in 2004–05 and then expanded it in 2008–09. Under the program, families must participate in FCPP and contribute toward the cost of developmental services provided by the state if:

- The child has a developmental disability or is eligible for services under the California Early Intervention Services Act.

- The child is under 18 years of age.

- The child lives at home.

- The child is not eligible for Medi–Cal (Medi–Cal is California’s version of the federal Medicaid program, which provides primary medical services for low–income persons).

- Family income is at or above 400 percent of the FPL based upon family size. (The 2010–11 FPL for a family of four is $22,050 so, 400 percent of FPL is $88,200.)

The FCPP requires qualifying families to share in the cost of respite, day care, and camping services (no other services are affected). The state does not directly collect money from affected families. Rather, the RCs determine the services that a consumer needs through the IPP development process. If the IPP includes services subject to the FCPP, then the RC calculates the family’s share of the cost of those services. The RCs pay the state’s share of the cost for the services to the service provider. Any remaining hours of services included in the consumer’s IPP are the financial responsibility of the family. (The service provider cannot charge a higher rate for the service than the rate paid by the RC.) However, a family can choose not to purchase all of the services for which it is financially responsible in order to hold down its costs. The family’s cost is calculated based upon a sliding scale ranging from 10 percent to 100 percent of the cost of the services that are purchased. Their proportion of costs reflects the number of persons living in a family’s home and the family’s gross annual income. Also, the maximum total cost that any family can be required to pay is capped and cannot exceed (1) $6,400 annually if the child is age 6 or younger, (2) $7,000 annually if the child is 7 through 12, and (3) $7,900 annually if the child is 13 through 17. The FCPP allows for an appeals process to resolve any error in the calculation of the cost participation rate or make an adjustment to the rate based on a family’s claim of financial hardship.

FCPP Could Be Expanded. The benefit to the state General Fund from the current FCPP is fairly limited in comparison to the $2 billion General Fund cost of the community services program. Total cost avoidance generated from this program is estimated now to be about $4 million annually. However, the FCPP could be extended to include the other services purchased by the RCs on behalf of consumers, such as transportation and day programs. (However, our approach would exclude services purchased from 24–hour care facilities such as a DC, community care facilities, or medical facilities, which are already subject to a parental fee program.)

We estimate that the savings from expanding the FCPP to all services would be about $10 million General Fund annually. For more information regarding this proposal, see our April 2009 report, Family Cost Participation Program Expansion, available on our website.

Families with developmentally disabled children and developmentally disabled adults are eligible for RC services irrespective of financial status. For most health and social services programs, applicants must demonstrate that they do not have the means to pay for services themselves or that they have limited means before the state will determine them eligible and provide assistance. This analysis provides some background on means testing and how it is applied in other programs. We also identify key issues that the Legislature would need to consider with regards to implementing means testing for RC services.

Most Health and Social Services Programs Are Means Tested. As noted above, for most health social services programs, eligibility is limited to persons who demonstrate that they do not have the means to pay for the services themselves, or that paying for the services would present a financial hardship. The determination of whether a person does not have the means to pay for a service, and is therefore eligible for a program, is often based upon the FPL—poverty guidelines issued each year in the Federal Register by the federal Department of Health and Human Services.

These guidelines are used by the federal government for statistical purposes, such as preparing estimates of the number of Americans in poverty each year. In addition, administrators of Medi–Cal and the Healthy Families Program (California’s version of the federal Children’s Health Insurance Program) use FPL guidelines to determine whether applicants are eligible for the program. For example, families with children 6 to 19 years of age generally must have annual incomes below 100 percent of FPL to be eligible for Medi–Cal. By comparison, families with incomes up to 250 percent of FPL may qualify for subsidized health insurance available through the Healthy Families Program for children.

For illustrative purposes, we estimated the state General Fund savings that could be achieved by implementing means testing for RC services based on the following key assumptions:

- Means Testing Would Be Implemented at 400 Percent FPL. We assumed that means testing would be imposed at 400 percent FPL, the same income level at which FCPP currently applies. However, means testing could be imposed at a lower or higher level of FPL, resulting in greater or lesser savings.

- Consumers 18 Years of Age and Older Would Be Excluded. We assumed in our example that means testing is applied only to families with developmentally disabled children (under age 18) living at home. We further assumed that consumers age 18 and over generally do not have annual incomes above 400 percent of FPL.

- About 9,700 Consumers Could Be Affected. Based on data that DDS provided in April 2009 regarding the number of current participants in FCPP, as well as our own estimates, we estimate that 9,700 consumers meet the criteria outlined above and would therefore be subject to means testing.

- Average Cost Per Client. We assumed that the average cost per client up to age 18 for all RC services is about $6,300 (excluding RC operations and 24–hour care). This is based upon the average cost per consumer for all RC services among FCPP participants in 2009. However, the average cost per consumer could have changed significantly between 2009 and the present. Thus, the savings from means testing could be higher or lower than we have assumed in our estimate.

- Savings from Existing FCPP. We assumed that means testing would replace the existing FCPP. Accordingly, we reduced our estimated savings to avoid double counting.

- Administrative Costs. We assumed in our example that the implementation of means testing would not result in any change in RC administrative costs. The RCs would continue to provide case management services, but would not purchase any services for consumers whose family incomes exceeded the 400 percent FPL limit.

- Means Testing Would Go into Effect July 1, 2011. We assumed that means testing would go into effect on July 1, 2011 and that full–year savings would be achieved.

- Increased Costs in Other Programs Could Offset Savings. The savings achieved through imposition of means testing could potentially be offset to some degree by increased costs in other programs. For example, “institutional deeming” is a process by which families can obtain full Medi–Cal health care program eligibility for children, such as those at risk of ending up in an institutional setting, who would otherwise be ineligible due to their family’s income level. It is possible that implementation of means testing could prompt more families to go through this Medi–Cal process. To the extent that this occurred, savings from means testing could be partially offset by increased costs in the Medi–Cal Program.

Based on these assumptions, we estimate the state could save $57 million in 2011–12 from implementing means testing.

Only a Small Percentage of RC Consumers Likely Subject to Means Testing. The RC caseload is estimated to grow to about 251,700 in the budget year. However, only a small percentage of these consumers would be affected by means testing—probably less than 5 percent under our illustration of the concept. There are two main reasons for this. First, roughly one–half of RC consumers are 18 or older and are unlikely to have incomes above 400 percent of FPL. Under our approach, in which their families were not held financially responsible for their services, they would not be affected by means testing. Second, most families have incomes below 400 percent of the FPL, the income level suggested in our example.

We highlight key issues for the Legislature to consider in its deliberations over whether to impose means testing on RC services.

At What Level Should Means Testing Be Set? For illustrative purposes, we have used 400 percent of FPL as a basis for calculating the savings that could be achieved through means testing. However, means testing could be imposed at a higher or lower level of the family’s FPL, with savings varying accordingly. In determining the income level for means testing, the Legislature should consider, among other factors, whether the cutoff for eligibility is consistent with its approach to means testing for other state health and social services programs. The Legislature should also consider whether the cutoff for eligibility should be phased into avoid a “cliff effect.”

Should There Be an Exceptions Process for Financial Hardship Cases? The Legislature may wish to consider whether there should be an exceptions process for families that would otherwise face very high costs for services for their children. While the average cost per consumer in our estimate is about $6,300, actual costs may vary widely from family to family. While the children in some families may only receive a few hundred dollars or less in annual RC purchase of services, others may now be receiving tens of thousands of dollars or more in annual assistance. An “exceptions” process could allow for the continuing provision of RC services in such cases of financial hardship. Depending on the level of financial hardship, a family could pay part or none of the costs of the services.

Should Means Testing Be Adjusted for Family Size? In establishing means testing for eligibility for RC services, the Legislature may wish to consider taking into account the number of children in a family that receives RC services. Notably, the costs charged to families under FCPP are adjusted based upon the size of a family, with some moderation of costs when more than one child in a family is receiving RC services and supports.

Should a Person Age 18 or Older Be Subject to Means Testing? In a few cases, some consumers age 18 or older may have income above the means testing income level that might be established by the Legislature. The Legislature may wish to consider whether such consumers should be subject to a means testing requirement.

Federal Approval May Be Required. Federal approval may be required to implement means testing for all the services that RCs purchase. For example, federal approval may be required form the U.S. Department of Education before means testing could be imposed upon families whose young children are in the Early Start program.

Should Means Testing Be Implemented Prospectively? Our savings estimate assumes that many families who currently receive services purchased for them by the RCs would be denied those services on July 1, 2011. However, one alternative would be to implement means testing on a prospective basis. Under this scenario, families that currently receive services would continue to receive them. However, families that apply for services on or after July 1, 2011, and who do not meet income eligibility requirements, would not have services purchased for their children by the RCs.

Should RCs Provide Case Management Services? The RCs could continue to provide some case management services to developmentally disabled children from families with incomes over the 400 percent FPL threshold. Under such an arrangement, the RCs would recommend appropriate services and refer families to service providers without paying for the services. If this policy were adopted, the state would have to fund the RC operations costs related to this caseload and forego the related savings. The advantage of this policy is that it would allow the RC to develop a working relationship with the consumer before the consumer turned 18 and the RC assumed responsibility for purchasing their services. It would also provide access to case management expertise to families at all income levels.

Adopt Specific Savings Measures. We recommend approval of the Governor’s budget proposal to extend the 4.25 percent provider payment reduction and the commensurate reduction to RC operations. Given the state’s severe fiscal problems, we believe continuing these cost–saving measures is reasonable and achievable. We also recommend approval of the Governor’s proposals to obtain additional federal funds for services provided through the DCs and the RCs.

Await Details on Unallocated Reductions. We withhold recommendation at this time on the administration’s proposal to achieve $533 million in General Fund savings until the department provides more specific information to the Legislature as to how these savings would be achieved. We recommend that the department provide the Legislature with specific standards for statewide services, estimated dollar reductions for each service standard, a timeframe for implementation, and proposed implementing language.

Implement Additional Savings Option. Given the rapid growth in the cost of the RC program, we recommend the Legislature either expand the existing FCPP or implement means testing to determine who is eligible to receive these state services. These changes, we would acknowledge, represent a significant departure from the policies originally adopted in the Lanterman Act. However, either of the approaches that we suggest would help ensure the long–term sustainability of the program for those consumers with the greatest financial need for its services.