The 2011–12 Governor’s Budget proposes a total of about $3.7 billion for the judicial branch from all fund sources—a decrease of $272 million (or 7 percent) from the revised current–year level. This amount includes roughly $1 billion from the General Fund, $860 million in a one–time transfer of redevelopment funding, and $499 million from the counties, with most of the remaining balance of about $1.3 billion derived from fine, penalty, and court fee revenues. The General Fund amount is a net decrease of $668 million, or 40 percent, from the revised current–year amount. (Adjusting for the shifts in redevelopment funding, the General Fund costs reduction would be $158 million, or 8 percent.) As displayed in the Governor’s budget, the above amounts do not reflect the impact of the administration’s proposal to realign funding for court security to counties, which we discuss in more detail below. In this brief, we (1) provide an overview of the Governor’s budget proposals for the judicial branch and (2) recommend specific actions to achieve savings, while at the same time minimizing the impacts on access to the courts.

The Governor’s budget includes both General Fund augmentations and reductions to the budget for the judicial branch. The major adjustments include:

- A $399 million increase primarily to replace redevelopment funds that were used on a one–time basis in 2010–11 to offset General Fund costs for trial courts.

- A $200 million (or roughly 5 percent) unallocated reduction to the judicial branch budget. This reduction would be ongoing.

- A $17.4 million reduction to the administration’s estimated workload budget for the judicial branch, as a result of its proposal to modify existing statutory requirements that trial courts provide greater oversight of conservators and guardians. Implementation of these provisions would be contingent on the availability of state funding for these purposes in future years.

The Governor’s budget also proposes a loan of $350 million from the State Court Facilities Construction Fund (SCFCF) to the state General Fund in 2011–12. The loan would be repaid, without interest, in 2013–14. According to the administration, the proposed loan would not delay any of the planned court construction projects supported by the SCFCF. In addition, under the Governor’s realignment plan, state funding to pay for security for trial courts would be shifted to counties and the state General Fund support in the judicial branch budget would be reduced by a commensurate amount.

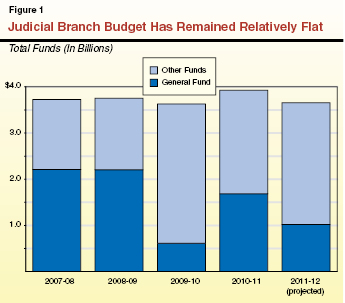

As shown in Figure 1, the judicial branch—and in particular the trial courts—have experienced reductions in General Fund support in the past several years. However, these reductions have been largely offset by fund shifts and additional revenue from court–related fee increases. As a result, the total level of funding for the judicial branch has remained relatively flat since 2007–08.

For example, the 2009–10 budget reduced General Fund support for the judicial branch by about $1.6 billion from the revised 2008–09 level of funding. However, this reduction was offset by a shift of redevelopment funding to the trial courts, as well as a shift of unspent balances from various special funds supporting the trial court operations and construction. In addition, the courts received additional revenue from increased court fees and fines (such as civil filing fees and court security fees). After taking all of these budgetary changes into account, the net result was only a reduction of $120 million in total funding for the judicial branch between 2008–09 and 2009–10.

We acknowledge that the amounts in Figure 1 are not adjusted for inflation. This is for two reasons: (1) inflation rates have generally been low and (2) state law adopted in 2009 expressly prohibits automatic annual price increases for the courts and most other areas of state government. At the same time, we acknowledge that any price increases experienced by the judicial branch have the effect of eroding their operational funding.

In view of the above and the state’s difficult fiscal problems, the Governor’s proposal to achieve $200 million in ongoing judicial branch savings merits serious legislative consideration. The administration, however, has not identified how the savings from the proposed unallocated reduction would be achieved. Rather, the administration has proposed working with the judicial branch to determine how this reduction would be accomplished. While we believe that the Legislature should carefully consider the advice of the judicial branch and stakeholders when setting funding levels, how any cut is made is also an important decision for the Legislature. A budget reduction of this size could significantly affect trial court operations, with civil cases disproportionately bearing the brunt of any delays in trials that resulted from a shortfall in available resources. That is because statutorily enforced timelines would force the judicial branch to give criminal cases higher priority in order to prevent the dismissal of charges against defendants.

With these factors in mind, we have identified specific actions for the Legislature to consider in implementing reductions for the judicial branch in a way that minimizes (but by no means eliminates) the impacts on access to the courts. The fiscal effects of our proposals, which we discuss in more detail below, are summarized in Figure 2. In total, our recommendations would achieve $356 million in savings for 2011–12—in excess of the $200 million assumed for that year in the Governor’s proposed budget. Upon full implementation of some measures, but the phase out of others with a limited effect, our proposed package would result in ongoing savings of $300 million after several years.

Figure 2

LAO Recommendations for Cost Savings in Judicial Branch

(In Millions)

|

Recommendation

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

Full Implementation

|

|

Implement electronic court reporting

|

$13

|

$34

|

$113

|

|

Ensure courts charge for civil court reporters

|

23

|

21

|

12

|

|

Implement competitive bidding for court security

|

20

|

40

|

100

|

|

Reduce trial court funding based on workload analysis

|

35

|

45

|

60

|

|

Contract out interpreting services

|

15

|

15

|

15

|

|

Reduce funding to account for trial court reserves

|

150

|

—

|

—

|

|

Transfer from Immediate andCritical Needs Account

|

100

|

50

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$356

|

$205

|

$300

|

Implement Electronic Court Reporting. Under current law, trial courts use certified shorthand reporters to create and transcribe the official record of many court proceedings. The prepared transcripts are effectively “owned” by the court reporters and, for certain types of cases, are purchased by the court. However, electronic court reporting systems involving audio and/or video devices could be used instead of court reporters to record the statements and testimony delivered in the courtroom. The actual recordings created during the proceedings could be used in a manner similar to a transcript, and the sales of these recordings could generate additional revenue for the court.

Currently, many state and federal courts—including the U.S. Supreme Court, the California Courts of Appeal, and the California Supreme Court—use electronic methods for recording court proceedings. Moreover, electronic court reporting was demonstrated to be cost–effective in a multiyear pilot study carried out in California courts between 1991 and 1994. The study found significant savings—$28,000 per courtroom per year in using audio reporting and $42,000 per courtroom per year using video—compared to using a court reporter. In addition to saving a substantial amount of funding, a switch to electronic court reporting would also help address a persistent problem faced by the courts in the past—a short supply of certified shorthand reporters.

In view of the above, we recommend the Legislature direct the trial courts to implement electronic court reporting in California courtrooms. In order to allow an appropriate transition to the use of this technology, we propose that 20 percent of the state’s courtrooms be switched to electronic reporting each year until the phase–in is complete. After factoring in the estimated one–time costs for audio and video equipment and adjusting the results of the above study for inflation, we estimate that the state could save about $13 million in 2011–12. Upon full implementation, the estimated savings could exceed $100 million on an annual basis.

Ensure Courts Charge for Court Reporting Services in Civil Cases. Under current law, court reporting services are provided in civil cases at the order of the court or at the request of a party to the case. Unlike criminal cases, however, the two parties involved in a particular civil case are required to pay the court for such reporting services for any proceeding lasting more than one hour on the first day and each succeeding judicial day of the proceeding.

Despite the above provisions, information provided to our office by the Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC) indicates that the actual costs of providing court reporting services in civil proceedings exceeds the amount of revenue collected in fees to pay for such services. For example, AOC reports that trial courts spent about $80 million for court reporting services in civil cases (including for those proceedings that lasted less than an hour) in 2009–10. However, the total fee revenue collected that year to offset these costs was only $30 million—resulting in a $50 million shortfall that was essentially funded by the state General Fund budget for the courts.

According to AOC, the existence of such a shortfall could be due to a variety of reasons. For example, courts may be waiving these fees for indigent individuals under certain circumstances. In addition, as mentioned above, parties to a case are not required to pay for reporting services in proceedings that last less than an hour. However, AOC also indicates that only 44 of the 58 trial courts reported receiving any revenue from fees for proceedings lasting more than one hour. While some small counties may not have had any civil proceedings that required court reporting services, the data suggest that some courts may not be collecting or imposing court reporting fees.

In order to ensure that trial courts collect the appropriate fees mandated under state law for court reporting services, we recommend that the Legislature reduce General Fund support for the trial courts to a level that reflects the aggregate amount of fees they should be collecting. Given the state’s massive General Fund shortfall, we also recommend amending existing state law to authorize trial courts to charge fees to offset all the cost of providing court reporting services —including proceedings lasting less than one hour.

Specifically, we recommend reducing the courts’ General Fund budget by $23 million in 2011–12 to account for the additional revenue that the courts are expected to receive from being more effective in imposing and collecting court reporting fees in civil proceedings (including those lasting less than an hour). This amount takes into account the number of individuals likely to qualify for fee waivers based on their income. Given our earlier recommendation to implement electronic court reporting, which would reduce court reporting costs, the amount of fee revenue from court reporting fees would decline in future years.

Current law generally requires trial courts to contract with their local sheriff’s offices for court security. Courts thus have little opportunity to influence either the level of security provided or the salaries of security officers. Accordingly, county sheriffs have little incentive to contain costs of the security provided, and the courts have no recourse to ensure that they do. Total security costs have increased from about $263 million in 1999–00 to roughly $500 million in 2009–10, for an average annual increase of about 7 percent. The Governor’s budget estimates that court security costs will be about $530 million in 2011–12. While most of these costs are funded each year from the General Fund, a small portion is funded with revenue collected from a $40 court security fee paid by individuals convicted of a criminal offense (including all non–parking traffic violations).

As previously mentioned, the Governor proposes to shift funding for court security from the trial courts to the counties as part of his overall state–local realignment plan. In our view, this approach does not make sense. While control of funding for court security would be shifted to counties, the state judicial system would continue to be responsible for the overall operation of the courts. Absent financial control, the courts would have difficulty ensuring that the sheriffs provided sufficient security measures.

We believe a better and more cost–effective alternative would be for the Legislature to direct the courts to contract on a competitive basis with both public and private security providers for the provision of security services. This new approach would probably have to be phased in over time to allow existing contractual obligations to expire. However, establishing a competitive bidding process would provide a strong incentive for whichever public agency (such as the sheriffs) or private firm that won the bid to provide security in the most cost–effective manner possible. Courts would be able to select among the proposals offered to them by different security providers, thus allowing them to select the level of security that best meets their needs. Depending upon when and how this change was implemented, we estimate that the state could save about $20 million in 2011–12 and that these savings could exceed $100 million annually within a few years.

In 2005, AOC and the National Center for State Courts completed an in–depth study on the level of funding a given trial court would need based on a specified workload, as measured in the number of cases filed. (This study is commonly referred to as the “resource allocation study.”) Specifically, the study analyzed the number and type of staff that a sample of various types of courts in California used to handle different types of case filings. This data was then used to calculate a base level of personnel—and by extension the amount of funding—that each trial court would need to effectively process the number and type of filings it typically receives. As a result, AOC is able to compare each court’s estimated budget need to its actual budget, in order to assess the adequacy of existing funding levels. For example, based on data from 2009–10, 13 of the 58 trial courts in the state received more funding—totaling $60 million—than needed to complete their workload. In other words, AOC’s resource allocation study suggests that these particular courts should be able to process their existing caseloads with less funding, while still achieving similar outcomes in terms of access to justice.

In order to achieve budgetary savings in a manner that minimizes the impact on trial court operations and services, we recommend that the Legislature more closely align the level of funding for the above 13 courts to their actual workload needs. We suggest phasing in these changes over a four–year period to give these courts time to adjust their operations. This would also give the Legislature the opportunity to reevaluate the funding needs of these courts in future years. In addition, we note that roughly 8 of these 13 trial courts had unrestricted reserves at the beginning of 2010–11. To the extent that these courts maintain such reserve balances, they would have additional flexibility to accommodate funding reductions in the short term. We estimate that our recommendation would achieve General Fund savings of $35 million in 2011–12 and $60 million upon full implementation in 2014–15.

The California Constitution and subsequent court rulings require that individuals with a limited ability to understand English be provided interpreting services in criminal, delinquency, and some family law matters. In addition, federal law specifies that individuals with hearing disabilities are entitled to interpreter services free of charge in all court proceedings. To address these requirements, the state court system directly employs about 757 interpreters and provides additional court interpreting services through independent contractors.

The court employees are compensated in one–half day increments, generally have benefits, and are compensated for travel costs. Their pay is not based on the number of cases they interpret or the actual amount of time they spend providing interpreting services. For example, an employee that interprets five cases over a four–hour period would be paid for a half day of service, as would an employee that interprets one case in a two–hour period. In 2007–08 (the most recent year for which court interpreter salary and usage data exists), trial courts paid their employed interpreters an average of $161 per case (including salary, benefits, and travel expenses). In contrast, courts only paid $68 per case on average in the same year to interpreters hired on a contract basis—about 58 percent less than their court employee counterparts. (Data from AOC indicates that contractors and court employees are assigned to different case types at very similar rates.)

Trial court costs for interpreting services have been growing. They amounted to $61 million in 2004–05, grew to about $88 million in 2009–10, and are expected to rise to $98 million in 2010–11. According to AOC, more than three–fourths of the 2009–10 funding was spent on interpreters who are court employees. The large proportion of monies going toward court employees reflects the constraints under existing state law on contracting out for interpreters. For example, courts typically contract out for interpreter services for a language that is not spoken by their regular employees. However, under certain circumstances, under state law the courts doing so must either offer the contracted interpreters regular employment or (eventually) create new positions for interpreters who speak the language for which they are relying on contractors to provide. Because court employees cost more than contractors, these requirements in state law have a tendency to increase state costs for the provision of these services.

Given that contracting out in general appears to be a more cost–effective approach to providing interpreter services in court proceedings, we recommend that the Legislature eliminate existing statutory restrictions on using contract court interpreters. We also note that greater reliance on independent contractors would allow the courts to more efficiently adjust their expenditures to the actual amount of interpreting services they need. This is because, while employee interpreters are not paid based on the amount of time actually spent interpreting, courts would be in a position to negotiate the fee they pay to independent contractors to match the precise amount of services they require from the contractor.

We estimate that greater use of contract reporters could initially save the state roughly $15 million. Actual savings in future years could be greater, but would depend in large part how courts implemented the proposed changes.

Under current law, individual trial courts are authorized to retain unexpended funds at the end of each fiscal year. As mentioned above, this has allowed some trial courts to accumulate significant reserve balances. For example, the trial courts had about $312 million in unspent funds at the beginning of 2010–11 that were not restricted by future contractual or statutory obligations, which is about 10 percent of the trial courts 2009–10 budget. In view of these significant reserves and the state’s massive General Fund shortfall, we recommend that the Legislature reduce funding for the trial courts on a one–time basis in 2011–12 by $150 million, and direct the trial courts to use their considerable reserve funds to buffer against the loss of state funding. The Legislature could also consult with the judicial branch to determine whether a different amount is justified in light of the other actions we have proposed to reduce court costs.

In 2008, the Legislature enacted Chapter 311, Statutes of 2008 (SB 1407, Perata), which increased civil and criminal fines and fees to finance 41 trial court construction projects that were deemed to be immediate and critical by the Judicial Council. The revenue resulting from the fine and fee increases is deposited in the Immediate and Critical Needs Account (ICNA) and used to pay off the debt services associated with the lease–revenue bonds used to construct the facilities. In recent years, the fund’s expenditures have been lower than anticipated by AOC. As a result, the ICNA is projected to have a year–end balance that is more than $100 million higher than expected over the next several years. In view of this, we recommend that the Legislature transfer $100 million to offset the General Fund costs of the trial courts in 2011–12 on a one time–basis. A separate $50 million could be transferred in 2012–13. Based on AOC’s projected revenues and expenditures, our recommendation would not delay any of the planned court construction projects supported by ICNA.

At the time this analysis was prepared, we had not yet received specific proposals from the judicial branch (or relevant stakeholders) on how to achieve the $200 million savings assumed in the Governor’s budget for 2011–12. We will review any such proposals put forward for legislative consideration, and will assess their impact on court users and the extent to which they create ongoing savings. The Legislature may find that these other proposals could have a lesser impact on court users than our recommendations and, thus, are worthwhile alternatives. However, if the Legislature is interested in creating savings in excess of the $200 million target assumed in the Governor’s budget, such proposals could be considered for adoption in addition to our recommendations.