Brief

April 15, 2024The 2024‑25 Budget

Child Care

Summary

This brief analyzes key Governor’s budget proposals related to various child care and development programs administered by the Department of Social Services (DSS).

Seems Reasonable to Rightsize General Child Care and Development (CCTR) Budget Based on Awarded Slots. Between 2020‑21 and 2022‑23, the state approved adding up to 50,080 new CCTR slots, increasing ongoing program costs by $1.1 billion. However, as of March 2024, only 21,194 of the 50,080 new slots have been awarded to providers. The Governor’s budget proposes to reduce CCTR funding levels to only reflect costs associated with the estimated number of awarded slots, resulting in $662 million total savings in 2023‑24 and $385 million total savings in 2024‑25 relative to the 2023‑24 Budget Act. (These savings are partially offset by costs associated with other proposed program changes.) Given the projected budget deficit, we believe it is reasonable to rightsize the CCTR budget to only reflect the amount of funding needed to implement the estimated number of awarded CCTR slots.

Recommend Rejecting Proposed Changes to Budgeting Process for New Child Care Slots and Developing an Alternative Approach. Historically, the Legislature would reach an agreement with the administration on the maximum number of new CCTR slots to be added in any given fiscal year and prospectively appropriate the necessary funds for DSS to award and implement all of the agreed upon slots. To rightsize the CCTR funding levels, the Governor’s budget proposes various changes to current budgeting practices and the implementation time line for new CCTR slots. These changes would significantly reduce legislative oversight and input over the slot expansion plan. Specifically, the proposed CCTR time line changes would allow DSS to issue annual requests for applications (RFAs) and award slots without the necessary legislative funding authority. While these changes would result in some initial General Fund savings, we do not believe the savings outweigh the trade‑off of side stepping the legislative budget process. We recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal. The Legislature could continue to use existing budgeting practices or develop an alternative approach to achieve the same savings.

Recommend Directing Administration to Prioritize Spending COVID‑19 Relief Funds to Minimize Federal Reversion and Maximize General Fund Savings. During the COVID‑19 pandemic, the state received over $5 billion in one‑time federal funds to support child care programs. Most of these funds expired September 30, 2023. The department is currently spending down the remaining $1.4 billion that expire September 30, 2024. Any unspent funds revert back to the federal government. We estimate that roughly $450 million of COVID‑19 relief funds may remain unexpended by the end of 2023‑24. We recommend the Legislature request the administration provide an updated May Revision estimate on (1) the total amount of COVID‑19 relief funds (including funds obligated in prior years) that would likely go unspent by the end of 2023‑24, and (2) what amount of these unspent funds could be used to effectively free‑up General Fund in 2024‑25. The Legislature could score the estimated amount of freed‑up General Fund as budget savings.

Recommend Consideration of Additional Budget Solutions. Given the deterioration in the state’s budget, additional solutions would help the Legislature close the deficit. Beyond the budget solutions included in the Governor’s budget, we identify roughly $1 billion in additional one‑time General Fund net savings across 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. These savings include sweeping unspent 2023‑24 funds and offsetting General Fund costs with newly available federal funds and carryover funds. (These savings would be partially offset by higher costs associated with collective bargaining agreement, required quality improvement activities, and previously awarded slots.)

Introduction

In this brief, we analyze the Governor’s budget proposals related to child care programs administered by DSS. (None of the child care and development proposals were addressed in early action.) We provide background on child care programs and an overview of total expenditures and budgeted slots included in the Governor’s budget. We then analyze key Governor’s budget proposals related to (1) ramp‑up assumptions and costs associated with the multiyear child care slot expansion plan, (2) Proposition 64 funding levels, (3) federal fund expenditures, and (4) implementation of the current collectively bargained child care Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) and parity agreement. We also identify potential budget solutions the Legislature could consider beyond what is include in the Governor’s budget.

Background

State Subsidizes Child Care, Primarily for Low‑Income Families. As shown in Figure 1, the state administers various child care and development programs. Most of the state’s subsidized child care is administered by DSS through three programs: (1) California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) child care, (2) the California Alternative Payment Program (CAPP), and (3) the CCTR program. CalWORKs child care programs focus on families enrolled in or transitioning out of CalWORKs welfare‑to‑work activities. The remaining programs are primarily designed for low‑income, working families that have not participated in CalWORKs. For example, the state operates the Migrant Alternative Payment Program (CMAP) and Migrant Child Care and Development Program that specifically serve migrant families that work in agriculturally related industries. Overall, families are eligible for subsidized child care if they have a family income of less than 85 percent of the state median income ($83,172 annual income for a family of three and $96,300 annual income for a family of four).

Figure 1

Overview of Child Care Programs

|

Program |

Descriptiona |

|

CalWORKs Child Care |

Provides subsidized child care services to current and former CalWORKs families. Slots are available to all children. |

|

California Alternative Payment Program |

Provides subsidized child care vouchers to working families. Slots are limited to budget appropriation. |

|

General Child Care and Development |

Directly contracts with center‑based and licensed family child care providers to serve working families eligible for subsidized care. Slots are limited to budget appropriation. |

|

CFCC Family Child Care |

Directly contracts with consortia of licensed family child care providers to serve working families eligible for subsidized care. Slots are limited to budget appropriation. |

|

Migrant Child Care |

Provides subsidized child care services to migrant families working in agriculturally related industries.b Services are provided throughout the Central Valley. Slots are limited to budget appropriation. |

|

Care for Children With Severe Disabilities |

Provides additional access to child care services for children under the age of 21 years and with exceptional needs.c Program is located in the San Francisco Bay Area. Slots are limited to budget appropriation. |

|

Emergency Child Care Bridge |

Provides temporary child care services to children in foster care system and under age 13. Child care services are temporary until family finds longer‑term child care solution.d |

|

aUnless otherwise specified, child must be under age 13 and families must earn at or below 85 percent of the state median income to be eligible for subsidized child care programs. For example, a family of three cannot earn more than $83,172 annually in 2023‑24 to be eligible for programs. bFamily earned at least 50 percent of their total gross income from employment in fishing, agriculture, or agriculturally related work during the 12 months immediately preceding the date of application for services. cChild must have an individualized education program or an individualized family service plan issued through a special education program. dChild care services provided up to 12 months, but may be extended for a compelling reason. |

|

Subsidized Child Care Costs Split Between Federal Government and the State. The state’s subsidized child care programs are primarily funded with state General Fund, with a substantial portion of costs also covered by various federal funding sources. The state uses federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families/Title XX funds to partially cover CalWORKs child care costs. Additionally, the state draws down federal Title IV‑E funds to partially cover Emergency Child Care Bridge program costs—referred to as the Bridge program—and federal Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) dollars to partially cover CAPP and CCTR program costs. As a condition of receiving CCDF dollars, the state must spend a portion of these dollars on activities intended to improve the quality of child care and establish a sliding fee scale for families receiving federally funded subsidized child care.

California Received Over $5 Billion in Temporary COVID‑19 Federal Relief Funds for Child Care. During the COVID‑19 pandemic, the federal government enacted three relief packages. Across these relief packages, the state received over $5 billion in one‑time federal funds to support child care programs. These funds must be obligated and liquidated by specific federal deadlines. Any unobligated or unliquidated funds revert back to the federal government. About $3.6 billion of the COVID‑19 relief funds expired on September 30, 2023. The remaining $1.4 billion in COVID‑19 relief funds were obligated by September 30, 2023 and need to expended by September 30, 2024.

State Also Funds Child Care Using Proposition 64 Revenue. In November 2016, California voters approved Proposition 64, which legalized the nonmedical use of cannabis. Proposition 64 created two excise taxes on cannabis: a retail excise tax and a cultivation tax. Chapter 56 of 2022 (AB 195, Committee on Budget) eliminated the cultivation tax on July 1, 2022. Proposition 64 revenues are allocated based on specific formulas. A portion of Proposition 64 revenues are deposited into the Youth Education, Prevention, Early Intervention, and Treatment Account (Youth Account), which funds child care, cannabis surveillance and education, local prevention programs, and youth community access grants. Since 2019‑20, the state has provided 75 percent of total Youth Account funds (minus $12 million that is earmarked for cannabis surveillance and education activities) for CAPP and CCTR slots. Proposition 64 revenues are continuously appropriated, meaning that they are allocated by the administration and are not subject to the legislatively driven annual budget process.

Governor’s Budget Proposals

Governor Proposes $7.2 Billion for Child Care Programs in 2024‑25. As shown in Figure 2, we estimate the Governor’s budget increases total funding levels for child care programs in 2024‑25 by $510 million (8 percent) relative to revised 2023‑24 levels—from $6.7 billion to $7.2 billion. The year‑over‑year net increase in child care expenditures reflects the net effect of cost increases, savings, and cost shifts. For example, the Governor’s budget includes about $460 million to increase CCTR and CAPP slots in 2024‑25. These costs increases are partially offset by the expiration of one‑time funding in 2024‑25 ($336 million total savings). Additionally, we estimate the Governor’s budget shifts about $900 million in program costs to the General Fund in 2024‑25 as a result of the expiration of COVID‑19 federal relief funds. As shown in Figure 3, under the Governor’s budget, proposed funding would support about 374,000 child care slots in 2023‑24 and 422,000 child care slots in 2024‑25. The year‑to‑year slot increase includes projected growth in CalWORKs child care programs (about 17,200 net slot increase) and scheduled slot increases in CAPP and CCTR (28,000 total slot increase).

Figure 2

Child Care Budget

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

Change From 2023‑24 |

|||

|

Amount |

Percent |

|||||

|

Expenditures |

||||||

|

CalWORKs Child Care Programs |

||||||

|

Stage 1 |

$532 |

$649 |

$709 |

$61 |

9% |

|

|

Stage 2c |

310 |

470 |

691 |

221 |

47 |

|

|

Stage 3 |

608 |

604 |

572 |

‑31 |

‑5 |

|

|

Subtotals |

($1,450) |

($1,723) |

($1,973) |

($250) |

(15%) |

|

|

Non‑CalWORKs Child Care Programs |

||||||

|

Alternative Payment |

$1,834 |

$2,054 |

$2,242 |

$189 |

9% |

|

|

General Child Care and Developmentd |

960 |

1,204 |

1,500 |

296 |

25 |

|

|

CFCC Family Child Caree |

53 |

54 |

54 |

—f |

1 |

|

|

Emergency Child Care Bridge |

97 |

94 |

94 |

— |

— |

|

|

Migrant Child Careg |

69 |

71 |

71 |

—f |

— |

|

|

Care for Children With Severe Disabilities |

2 |

2 |

2 |

—f |

2 |

|

|

Subtotals |

($3,015) |

($3,478) |

($3,964) |

($486) |

(14%) |

|

|

Support Programs |

$2,187 |

$1,539h |

$1,313i |

‑$226 |

‑15% |

|

|

Totals |

$6,653 |

$6,740 |

$7,250 |

$510 |

8% |

|

|

Funding |

||||||

|

Proposition 98 General Fundj |

$2 |

$3 |

$2 |

‑$1 |

‑37% |

|

|

Non‑Proposition 98 General Fund |

2,275 |

3,283 |

4,756 |

1,473 |

45 |

|

|

Proposition 64 Special Fund |

292 |

270 |

247 |

‑23 |

‑8 |

|

|

Federal |

4,084 |

3,183 |

2,245 |

‑938 |

‑29 |

|

|

aReflects 2023‑24 May Revision estimates with LAO adjustments. bReflects 2024‑25 Governor’s Budget. cDoes not include $11.2 million provided to community colleges for certain child care services. dReflects funding for centers and family child care home education network providers operating through general child care and development contract. eReflects funding for family child care home education networks operating through CFCC contract. fLess than $500,000. gReflects costs associated with Migrant Child Care and Development program and Migrant Alternative Payment program. hIncludes cost estimates for quality programs, child care infrastructure, Child and Adult Care Food Program, CCPU Retirement Benefit Trust, accounts payable, whole child community equity, court cases, and costs associated with 2023‑24 collective bargaining and parity agreement. iIncludes cost estimates for quality programs, Child and Adult Care Food Program, accounts payable, whole child community equity, and costs associated with 2023‑24 collective bargaining and parity agreement. jReflects Proposition 98 funds for Child and Adult Care Food Program. |

||||||

|

CCPU = Child Care Providers United. |

||||||

Figure 3

Child Care Subsidized Slots

|

2020‑21 Final |

2021‑22 Revised |

2022‑23 Revised |

2023‑24 Revised |

2024‑25 Proposed |

Change From 2023‑24 |

|||

|

Amount |

Percent |

|||||||

|

CalWORKs Child Care |

||||||||

|

Stage 1 |

25,018 |

29,066 |

48,095 |

58,322 |

63,241 |

10,227 |

18% |

|

|

Stage 2 |

55,484 |

25,718 |

26,705 |

38,427 |

57,220 |

11,722 |

31 |

|

|

Stage 3 |

66,073 |

62,464 |

56,191 |

51,421 |

47,782 |

‑4,770 |

‑9 |

|

|

Subtotals |

(146,575) |

(117,248) |

(130,991) |

(148,170) |

(168,243) |

(17,179) |

(12%) |

|

|

Non‑CalWORKs Programs |

||||||||

|

Alternative Payment |

66,712 |

129,332 |

161,332 |

161,332 |

177,332 |

16,000 |

10% |

|

|

General Child Care and Developmenta |

28,375 |

37,179 |

49,569 |

49,569 |

61,569 |

12,000 |

24 |

|

|

CFCC Family Child Careb |

3,816 |

3,816 |

3,816 |

3,816 |

3,816 |

— |

— |

|

|

Emergency Child Care Bridge |

5,037 |

5,537 |

5,537 |

5,537 |

5,537 |

— |

— |

|

|

Migrant Child Carec |

3,962 |

5,262 |

5,262 |

5,262 |

5,262 |

— |

— |

|

|

Care for Children with Severe Disabilities |

111 |

111 |

111 |

111 |

111 |

— |

— |

|

|

Subtotals |

(108,013) |

(181,237) |

(225,627) |

(225,627) |

(253,627) |

(28,000) |

(12%) |

|

|

Totals |

254,588 |

298,485 |

356,618 |

373,797 |

421,870 |

45,179 |

12% |

|

|

aReflects slots for centers and family child care home education network providers operating through general child care and development contract. bReflects slots for family child care home education networks operating through CFCC contract. cReflects slots for Migrant Child Care and Development program and Migrant Alternative Payment program. |

||||||||

|

Note: Reflects Department of Social Services slot estimates. Under the 2024‑25 Governor’s Budget, the number of budgeted slots in each program reflects projections of filled or awarded slots beginning in 2021‑22, which is different from historical budgeting practices. Stage 2 does not include certain community college child care slots (less than 1,000 slots annually). |

||||||||

We Estimate Roughly $700 Million of Child Care Funds May Go Unspent by the End of 2023‑24. As a part of the 2023‑24 budget, the Legislature adopted supplemental reporting language that required DSS to provide, on or before March 1, 2024, an estimate of child care program funds that may go unspent by the end of 2023‑24 and what amount of unspent funds cannot be reappropriated and would revert back to the state or federal government. Thus far, the administration has provided a point‑in‑time estimate of unspent child care funds. Specifically, the administration estimates that about $1.4 billion of the funds that were obligated to be expended in 2023‑24 and have been put into contract remain unspent as of the end of January 2024. To the extent monthly expenditure trends continue at current levels, we estimate that roughly $700 million ($450 million COVID‑19 federal relief funds and $250 million other funds) could go unspent by the end of 2023‑24. (In later sections we discuss in more detail the slower than expected expenditure trends in certain fund sources.)

Budget Includes Four Major Child Care Proposals. The Governor’s budget includes four major child care proposals that change implementation of existing policies, update estimates of certain funding sources, and provide updated estimates of certain costs. In the rest of this brief, we cover these proposals in more detail.

LAO Bottomline: Recommend Consideration of Additional Budget Solutions. Given the projected budget deficit, we recommend the Legislature (1) proactively revert any unspent General Fund dollars from the 2023‑24 fiscal year, and (2) explore ways to offset General Fund costs in 2024‑25 with unspent funds from other fund sources. As shown in Figure 4, we estimate these actions could yield roughly $1 billion in one‑time General Fund net savings across 2023‑24 and 2024‑25 beyond what is included in Governor’s budget. To get a more accurate estimate of potential savings, we recommend the Legislature direct the administration to provide an updated estimate of potential 2023‑24 unspent funds that include more recent monthly expenditure trends, uncontracted funds, and unspent COVID‑19 federal relief funds from prior years that would expire on September 30, 2024.

Figure 4

Recommend Scoring Additional One‑Time

General Fund Savings

LAO Estimates (In Millions)

|

Additional Savings |

|

|

Offset costs with unspent COVID‑19 federal relief fundsa |

$450 |

|

Offset costs with Proposition 64 carryover fundsb |

415 |

|

Proactively sweep potential unspent 2023‑24 fundsc |

280 |

|

Offset costs with additional CCDFd |

89 |

|

Offset Emergency Child Care Bridge costs with 2022‑23 carryover funds |

40 |

|

Additional Costs |

|

|

Increase funding to cover higher than estimated MOU and parity costs |

‑$107 |

|

Increase funding to reflect actual CCTR award amounts |

‑22 |

|

Net Savings |

$1,145 |

|

aAssumes funds can offset slot costs and free‑up General Fund. bReflects administration’s estimate of carryover balance by the end of 2023‑24. Proposition 64 revenues are continuously appropriated, meaning the administration would need to redirect carryover funds to offset General Fund costs. cReflects rough LAO estimate of program funds that will go unspent by end of 2023‑24, including estimate of $30 million unspent General Fund from the Emergency Child Care Bridge program. Assumes savings from non‑General Fund sources can be used to offset General Fund costs in 2023‑24. dReflects net amount of available CCDF dollars after backing out increase to federally required CCDF quality set aside (about $10 million). |

|

|

CCDF = Child Care and Development Fund; MOU = Memorandum of Understanding; and CCTR = General Child Care and Development. |

|

Child Care Slot Expansion Plan

Background

Legislature and Administration Agreed Upon Multiyear Child Care Slot Expansion Plan in 2021‑22. The 2021‑22 budget agreement intended to increase the number of child care slots by 206,500 across CAPP (142,620 slots), CCTR (62,080 slots), CMAP (1,300 slots), and Emergency Child Care Bridge (500 slots). Initially, these new slots were expected to be fully rolled out by 2025‑26. However, as part of the 2023‑24 budget, the slot expansion plan was paused for one year, delaying the full roll out to 2026‑27 (see Figure 5). The details of the slot expansion plan are not codified in statute, but are tracked by the administration and Legislature. The administration estimates that sufficient funding has been provided in prior budgets to fully roll out all intended new CMAP and Emergency Child Care Bridge slots. The state is still in the process of rolling out all intended new CAPP and CCTR slots.

Figure 5

Child Care Slot Expansion Plan Under 2023‑24 Budget Acta

New Slots Added by Program

|

Programs |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

2026‑27 |

Total |

|

General Child Care and Development |

46,080 |

4,000 |

— |

4,000 |

4,000 |

4,000 |

62,080 |

|

Alternative Payment |

62,620 |

32,000 |

— |

16,000 |

16,000 |

16,000 |

142,620 |

|

Migrant Alternative Payment |

1,300 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

1,300 |

|

Emergency Child Care Bridge |

500 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

500 |

|

Totals |

110,500 |

36,000 |

— |

20,000 |

20,000 |

20,000 |

206,500 |

|

aDoes not include proposed changes to CCTR ramp up under 2024‑25 Governor’s Budget. |

|||||||

Funding for New CAPP Slots Is Awarded to Existing Alternative Payment (AP) Agencies. DSS currently contracts with about 70 regional AP agencies to administer CAPP. AP agencies’ primary responsibilities are to determine a family’s eligibility for child care, make payments to the child care provider of a family’s choice, collect fees from certain families, ensure families and providers are complying with state rules and regulations, and create and maintain detailed records about each family and provider. Total contract levels reflect funds needed to cover program service and administrative costs. Additional funds for new CAPP slots are generally distributed proportionately across existing AP agency contracts.

New CCTR Funds Are Awarded Through an RFA Process. DSS currently contracts directly with over 350 private agencies, local education agencies, tribes and tribal organizations, and other local governments that provide child care through the CCTR program. Under the CCTR program, child care services are provided through centers and family child care home education networks. Total contract levels reflect funds needed to cover program service and administrative costs. Additional funds for new CCTR slots are generally awarded to providers through a competitive RFA process. The department generally releases an RFA in the fall following the legislative approval of additional funds to award new CCTR slots. Under the RFA process, providers must fill out an application explaining their program philosophy, intended service levels, staff qualifications, facility capacity, family engagement strategies, and finances. The department approves applications and issues slot award letters in the spring. Additionally, the department allocates funds for new CCTR slots to selected providers by either amending existing provider contracts or issuing new contracts to providers not currently involved in the CCTR program. While previous budgets assumed CCTR contracts for newly awarded slots would be in place on the same date as award letters are issued, it realistically takes DSS several months to finalize these contracts.

Funding for Slot Expansion Typically Not Fully Spent in Initial Years. After DSS allocates and awards new CAPP and CCTR slots, it typically takes agencies and providers a few months to ramp up capacity to recruit, enroll, and serve additional children. Additionally, some budgeted new CCTR slots may ultimately go unawarded to the extent the department does not receive enough applications. In both cases, a portion of budgeted funds for new slots would go unspent, resulting in one‑time savings. Historically, the state would continue to appropriate the same amount of funding needed to fully implement all new CAPP and CCTR slots regardless if the actual number of filled or awarded slots fell below budgeted levels. Any unspent funds result in state savings in subsequent years.

Historically, CAPP and CCTR Contracts Are Not Finalized Until After Legislative Approval of State Budget. Overall, DSS does not release any program funds until contracts have been finalized and executed. In past years, DSS would not award or place into contract funds for new slots until the funds were approved and appropriated by the Legislature through the annual budget process. For example, in 2022‑23, the department began to amend initial CAPP contracts after July 1, 2022 with the goal of implementing all the new 2022‑23 slots as early as October 1, 2022. For CCTR, the department released an RFA in the fall of 2022, with the goal of awarding and implementing new 2022‑23 slots as early as April 1, 2023. The department also released an RFA in the fall of 2023 and is currently in the process of determining provider award amounts. The 2023‑24 Budget Act appropriated $1.1 billion to support up to 50,080 new CCTR slots intended to be awarded through these RFAs. However, only 21,194 slots have been awarded thus far.

Funding for Emergency Child Care Bridge Allocated to Opt‑In Counties. In 2017‑18, the state created the Bridge program. This program aims to stabilize foster placements by providing (1) time‑limited vouchers for immediate child care services until an ongoing child care slot becomes available in the regular subsidized child care system, and (2) child care navigators to assist resource families in accessing long‑term subsidized child care. Additionally, the Bridge program provides participating child care providers with trauma‑informed training and coaching. The Bridge program is jointly administered by DSS and county welfare departments. County participation in the Bridge program is voluntary. Currently, 48 counties are participating in the Bridge program. Funding for the Bridge program is capped and generally consists of a mix of General Fund, Proposition 64 funds, and federal Title IV‑E funds.

Governor’s Budget

Modifies Ramp‑Up Schedule for New CCTR Slots, but Continues to Assume All New Slots Are Rolled Out by 2026‑27. While the Governor’s budget continues to assume a total of 62,080 new CCTR slots will be added by 2026‑27, the administration proposes changes to how these slots are phased in relative to 2023‑24 Budget Act. As a result of these and other changes to the CCTR budgeting process and RFA time line, the Governor’s budget includes, on net, $581 million total savings in 2023‑24 and $318 million total savings in 2024‑25. We describe these changes in more detail below.

- Reduces CCTR Budget to Only Reflect Estimated Number of Awarded Slots, Resulting in $662 Million Total Savings in 2023‑24 and $385 Million Total Savings in 2024‑25. Between 2020‑21 and 2022‑23, the state increased funding to support up to 50,080 new CCTR slots, resulting in a $1.1 billion ongoing increase to total program costs. However, as of March 2024, only 21,194 of the 50,080 new CCTR slots have been awarded to providers. The Governor’s budget proposes to reduce CCTR funding levels in 2023‑24 to only reflect costs associated with the estimated number of awarded slots, resulting in $662 million total savings relative to the 2023‑24 Budget Act. Similarly, the Governor’s budget proposes to fund a total of 33,194 new CCTR slots in 2024‑25, which is about 21,100 fewer slots than what would have been funded under current budgeting practices. This slot difference results in $385 million savings in 2024‑25. (The 2023‑24 and 2024‑25 savings are partially offset by costs associated with other proposed program changes discussed in more detail later in this section.)

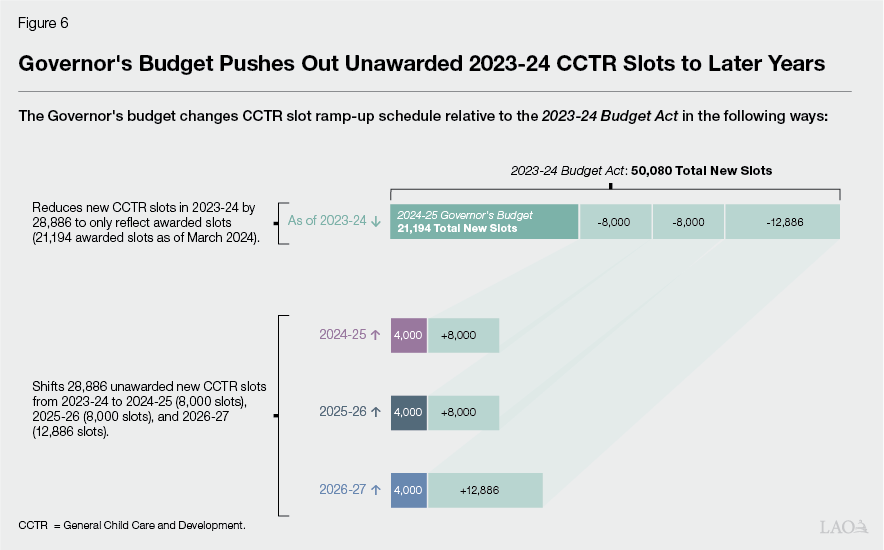

- Pushes Out Unawarded CCTR Slots From 2023‑24 to Later Years. As previously mentioned, the Governor’s budget reduces the number of budgeted new CCTR slots by 28,886 in 2023‑24—from 50,080 to 21,194—to reflect the current number of awarded slots. As shown in Figure 6, the Governor’s budget assumes the 28,886 unawarded CCTR slots are phased in across 2024‑25 to 2026‑27 instead.

- Updates Total Costs Associated With New CCTR Slots Awarded in Fall 2021 RFA and Fall 2022 RFA to Reflect More Recent Cost Per Slot Data. Under the 2023‑24 Budget Act, DSS estimated each new CCTR slot would cost about $22,470 annually across 2021‑22 to 2026‑27. The Governor’s budget estimates that the average costs of new CCTR slots awarded between 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 is about $26,380 annually (17 percent higher than past estimates), increasing total costs for the slot expansion plan by $81 million in 2023‑24. Similarly, the Governor’s budget assumes the annual cost per slot after 2023‑24 is about $23,150 (3 percent higher than past estimates), increasing total costs for the slot expansion plan by $8 million annually from 2024‑25 to 2026‑27. We understand that the revised cost per slot estimate reflects more recent data on actual program costs.

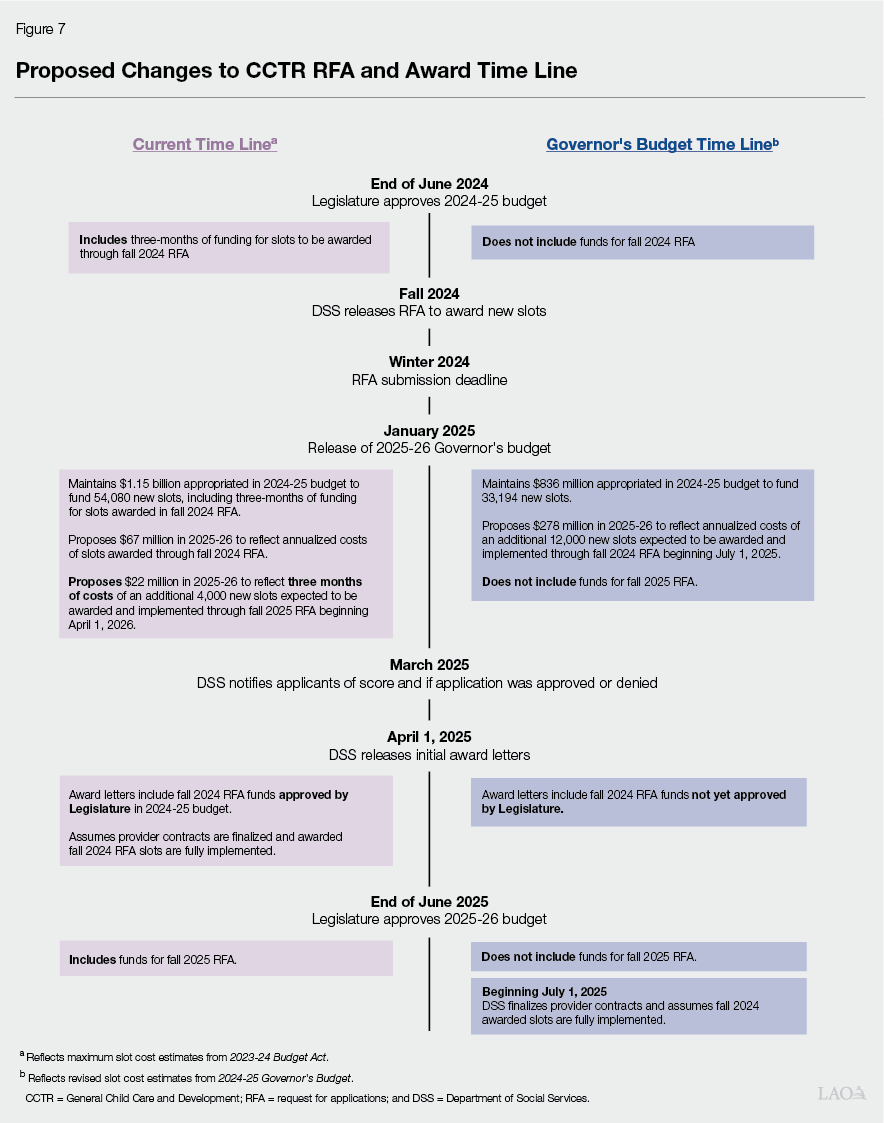

Changes Budgeting Process and Time Line to Award, Put Into Contract, and Implement New CCTR Slots. The Governor’s budget proposes multiple changes to the timing in which new CCTR slots are awarded, put into contract, and implemented. We compare the various proposed changes to the current time line in Figure 7. (Costs in the current time line are based on 2023‑24 Budget Act maximum slot cost estimates.) Overall, we estimate these changes eliminate the need to provide three months of slot funding—$22 million General Fund—in the remaining years of the CCTR slot expansion plan. We explain the proposed time line changes and associated cost impacts in more detail below.

- Assumes Later Implementation Date for CCTR Slots Awarded Through Fall 2023 RFA. Although the state did not provide funding for new slots in 2023‑24, the department was able to issue an RFA in the fall of 2023 given the significant amount of previously appropriated funding that had not yet been awarded to providers. As a result of the fall 2023 RFA, the department anticipates awarding at least 12,000 CCTR slots in April 2024. Under the state’s current budgeting practices, the state would have assumed all of these awarded CCTR slots would be implemented in April 2024, resulting in three months of costs in 2023‑24. However, the Governor’s budget assumes all awarded CCTR slots from the fall 2023 RFA would be implemented in July 2024. As a result, the Governor’s budget does not need to provide three months of slot funding in 2023‑24 ($22 million General Fund). The administration assumes the new July implementation date assumption will apply to all new CCTR slots awarded in future years.

- Assumes DSS Would Release Future RFAs and Award New CCTR Slots Prior to Legislative Approval. By continuing to appropriate funds for slots that had not yet been awarded, the 2023‑24 Budget Act provided DSS with the necessary funding authority to release a fall 2023 RFA and issue award letters in the spring of 2024. We understand that DSS plans to release a fall 2024 RFA and issue award letters in the spring of 2025. Based on current budgeting practices, the administration would have sought legislative approval to set aside at least three months of new slot funding as a part of the 2024‑25 budget process so that DSS has an authorized funding stream to release a fall 2024 RFA and award slots in the spring of 2025. However, the Governor’s budget does not propose to provide any funding in 2024‑25 to support slots awarded through the fall 2024 RFA (see Figure 7). The administration instead plans to seek legislative approval for the necessary funding authority for the fall 2024 RFA as part of the 2025‑26 budget process. As a result of no longer proactively proposing a three month set‑aside to support future RFAs and award letters, total CCTR program costs decrease by $22 million General Fund in 2024‑25 relative to the 2023‑24 Budget Act.

- Includes Provisional Language Allowing Administration to Increase CCTR Funding Levels Mid‑Year. The Governor’s budget proposes provisional budget language that would allow the Department of Finance (DOF) to increase CCTR funding levels mid‑year if expenditures are “estimated to exceed the expenditures authorized” in the 2024‑25 budget. While DOF would be required to report any mid‑year augmentations to the Legislature, legislative approval would not be required for the funding augmentation to take effect.

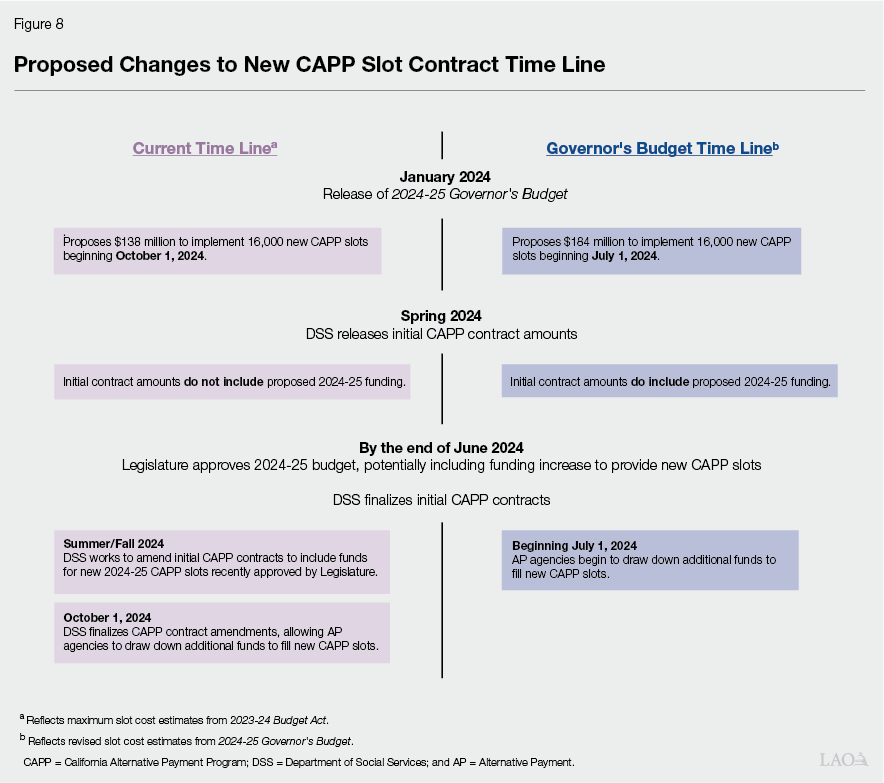

Assumes DSS Would Allocate and Execute Contracts for Future New CAPP Slots Prior to Legislative Approval. Consistent with the multiyear expansion plan, the Governor’s budget proposes to provide 16,000 new CAPP slots in 2024‑25. Under current budgeting practices, the department would have waited until after July 1, 2024 (or when the Legislature approves the 2024‑25 budget) to allocate the new CAPP slots and amend existing contracts to include additional funds. Under this practice, the state would have assumed new slots would be allocated and implemented beginning October 1 and would have provided nine months’ worth of funding in the first year of implementation ($138 million General Fund). However, as shown in Figure 8, the Governor’s budget assumes new CAPP slots will be allocated and implemented beginning July 1 and provides 12 months’ worth of funding in 2024‑25 ($184 million General Fund). Compared to current budgeting practice of assuming an October 1 implementation date, this results in $46 million additional General Fund costs in 2024‑25. Additionally, to meet the July start date, DSS would need to allocate and add funds for new CAPP slots to existing CAPP contracts in the spring of 2024—prior to enactment of the 2024‑25 budget.

Assumes Temporary Ineligibility of Federal Funding for Emergency Child Care Bridge Vouchers, Effectively Reducing Budgeted Slots by Roughly 1,400. The Governor’s budget provides a total of $94 million ($83 million General Fund, $7 million Title IV‑E, and $4 million Proposition 64 funds) in 2023‑24 and 2024‑25 to support the Bridge program. Of these funds, $58 million is provided to cover costs associated with Bridge child care vouchers. In the past, the state has also drawn down between $10 million and $20 million in additional federal Title IV‑E funds to partially cover Bridge voucher costs. The Governor’s budget, however, assumes the state would be ineligible to draw down any federal Title IV‑E funds for Bridge vouchers in 2023‑24 and 2024‑25 due to the continuation of the reimbursement flexibility policy. (A total of $7 million in Title IV‑E funds would still be drawn down for other components of the Bridge program.) During COVID‑19, the state modified reimbursement rules and allowed providers to effectively draw down reimbursement payments for child care vouchers that exceed actual service costs. This policy was set to expire June 30, 2023, but was extended for an additional two years under the child care MOU and parity agreement and 2023‑24 Budget Act. We understand that federal Title IV‑E funds can only be drawn down to cover costs associated with actual service costs. As a result, the state is ineligible to draw down $21 million in federal Title IV‑E funds for Bridge vouchers in 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. The Governor’s budget does not propose to backfill this temporary loss of federal Title IV‑E funds. We estimate that this results in a reduction in funding for Bridge vouchers that is equivalent to roughly 1,400 slots.

Assessment

Governor’s Budget Does Not Include the Right Amount of Funding to Support Previously Awarded CCTR Slots, but Will Be Corrected in May Revision. Across the fall 2021 RFA and fall 2022 RFA, the state awarded on an ongoing basis a total of $559 million for new CCTR slots. However, the Governor’s budget only includes $544 million total funds in 2023‑24 and $552 million total funds in 2024‑25 to cover these costs. We understand the administration plans to increase CCTR funding levels by $15 million General Fund in 2023‑24 and $7 million General Fund in 2024‑25 to reflect actual awarded levels as part of the May Revision. This would partially offset the net savings associated with the previously mentioned changes to the CCTR ramp‑up schedule and RFA time line ($581 million in 2023‑24 and $318 million in 2024‑25).

Seems Reasonable to Push Out Funding for New CCTR Slots Based on Current Slot Take‑Up Trends and Projected Budget Deficit. As a part of the 2023‑24 Budget Act, the state reduced 2022‑23 CCTR funding levels to reflect more realistic estimates of expenditures based on the actual number of awarded CCTR slots. Similarly, the Governor’s 2024‑25 budget reduces the number of funded CCTR slots to only reflect estimates of awarded slots on an ongoing basis. We estimate this change has the effect of reducing total CCTR slot costs, on net, by about $570 million in 2023‑24 and about $310 million in 2024‑25 relative to the 2023‑24 Budget Act. We believe this is a reasonable budgeting approach given the slower than expected take‑up of new CCTR slots and projected budget deficit. (However, we do have concerns with changes to CCTR budgeting process and time line the administration proposes to achieve these savings, which we discuss in more detail later in this section.)

Slower Than Expected CCTR Slot Take‑Up May Be, in Part, Due to Delays in Contracting Processes. We understand that it takes DSS, on average, between six to seven months to finalize and execute a contract once new CCTR slot funds are awarded to providers. This exceeds the Governor’s budget assumption that final CCTR contracts will be executed within three months following the award date. Based on conversations with the department and providers, the delay in executing contracts may be due to various reasons, including the department prioritizing amending contracts for existing providers before executing contracts for new providers, new providers needing additional technical assistance to obtain a state license, and providers receiving conflicting guidance from different DSS staff members on supporting documents needed to execute contracts. Additionally, some CCTR providers have expressed that, given the contracting delays, they may be less likely to apply for additional slot funding in future years.

Changes to CCTR Budgeting Process and Time Line for New Slots Reduces Legislative Oversight of the Slot Expansion Plan. Historically, the Legislature reached an agreement with the administration on the maximum number of new CCTR slots to be added in any given fiscal year and associated funding levels. We are concerned that allowing the administration to release RFAs and award new CCTR slots prior to the enactment of the state budget gets ahead of the Legislature’s appropriation authority. Decisions regarding budgeted slots would effectively be based on the spring RFA process, which is completely controlled by the administration. Furthermore, while the provisional language in the Governor’s budget requires notification to the Legislature, ultimately it would allow the administration to independently increase CCTR funding levels beyond what was appropriated by the Legislature through the budget process.

Unclear Under What Conditions Administration Would Use Provisional Language to Increase CCTR Funding Levels Mid‑Year. The proposed provisional language lacks any detail on how DOF would go about determining whether CCTR funding levels should be increased. Based on our conversations with the administration, CCTR funding levels could be increased if actual costs for slots awarded through the fall 2023 RFA exceed budgeted levels. For example, CCTR funding levels could be increased to address higher than expected cost per slot. Under this scenario, it is unclear how big of a cost difference the administration would need to observe to make a mid‑year adjustment. The administration also expressed that provisional language may allow the administration to increase CCTR funding levels in order to issue another RFA and award additional CCTR slots above what was authorized in the 2024‑25 budget to the extent provider demand and capacity increases. However, it is unclear how the administration would go about monitoring provider demand and capacity throughout the fiscal year and what amount of excess provider demand and capacity would need to be observed for the administration to make a mid‑year adjustment. We also do not know to what extent the administration would consider broader issues, such as the projected multiyear budget deficit, prior to making any mid‑year funding adjustments.

Governor’s Budget May Underestimate Costs Associated With Future CCTR Slot Expansions. As previously mentioned, the Governor’s budget increases the annual cost per slot estimate for CCTR slots awarded in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 by 17 percent (from about $22,470 to $26,380). However, the Governor’s budget only slightly increases the annual cost for slots awarded and implemented between 2024‑25 to 2026‑27 by 3 percent (from about $22,470 to $23,150). To the extent CCTR slot costs come in higher during this period, the Governor’s budget would underestimate the ongoing cost of the slot expansion plan. Specifically, we estimate the costs of the CCTR slot expansion plan would be $119 million higher at full implementation if we assume the higher cost per slot estimate across 2024‑25 to 2026‑27. (We are awaiting responses from DSS explaining the methodology used to estimate costs associated with scheduled CCTR slot increases.)

Assuming Earlier Implementation of New CAPP Slots Gets Ahead of Legislative Authorization and Increases Costs. We understand that one potential benefit to assuming an earlier July 1 implementation date in CAPP is that DSS would be able to incorporate additional slot funds in initial contracts rather than having to take the extra step to amend contracts after July 1. Additionally, we understand that incorporating additional funds for new CAPP slots in initial July 1 contracts could make it easier for AP agencies to budget expenditures on an annual basis. Depending on how quickly AP agencies ramp up internal capacity to administer new CAPP slots, families may also be served earlier. This proposal, however, would effectively eliminate legislative oversight of total CAPP funding levels by allowing DSS to issue and execute contracts with additional slot funds prior to the Legislature enacting a state budget. Moreover, the projected budget deficit makes it so that the state would need to identify $46 million in other budget solutions in each of the next three years to afford this proposal.

Actual Bridge Voucher Expenditures Likely to Come in Lower Than Budgeted Levels in 2023‑24. Since the inception of the Bridge program, actual program expenditures for Bridge vouchers have generally come in below budgeted levels. For example, in 2020‑21 and 2021‑22, about $13 million General Fund of annual Bridge voucher funding went unspent. In 2022‑23, the amount of unspent Bridge voucher funding increased to about $40 million General Fund. Based on most recent program data, monthly Bridge child care voucher levels in 2023‑24 are relatively equal to 2022‑23 levels. To the extent this trend continues, we estimate that actual Bridge voucher costs in 2023‑24 may be roughly $30 million General Fund lower than total budgeted levels.

Governor’s Budget Does Not Include Carryover of Unspent 2022‑23 Bridge Voucher Funds Into 2023‑24. In past years, DSS carried over unspent Bridge voucher funds into the following fiscal year. The Governor’s budget, however, does not display the availability of the 2022‑23 carryover funds in 2023‑24. If these unspent funds were accounted for, total Bridge voucher costs could be offset by $40 million General Fund in 2023‑24.

Recommendations

Adopt Governor’s Proposed CCTR Funding Levels to Only Reflect Awarded New Slots. Given the projected budget deficit, we believe it is reasonable to right‑size the CCTR budget to only reflect the amount of funding needed to implement the estimated number of awarded CCTR slots. This approach would free‑up hundreds of millions of one‑time General Fund dollars in a time where the state is projected to not have enough state resources to afford existing spending commitments.

Reject Proposed Changes to Budget Process and Time Line for New CCTR Slots. We believe the administration’s proposed changes to the process for issuing new CCTR slots would significantly reduce legislative oversight and input over the slot expansion plan. Specifically, the proposed CCTR time line changes would allow DSS to issue annual RFAs and award slots without the necessary legislative funding authority. While this change would result in some initial General Fund savings, we do not believe the savings outweigh the trade‑off of side stepping the legislative budget process. Additionally, the proposed provisional language would allow the administration to independently change the total CCTR funding levels and potentially the total number of funded CCTR slots through mid‑year adjustments. The Legislature could reject the Governor’s proposal and continue to use the existing process, where RFAs are based on the amount of funding provided in the enacted budget. Under this approach, the Legislature could include a modest amount of funding in the 2024‑25 budget as a way to provide DSS with the necessary funding authority to release a fall 2024 RFA. The Legislature could also develop an alternative budgeting approach that achieves the same amount of General Fund savings, avoids any cost increases, and maintains legislative oversight. For example, the Legislature could codify the ramp‑up schedule for the child care slot expansion plan to maintain legislative input over the maximum number of slots the administration could award in any given year.

Reject Proposed Changes to Time Line for Awarding New CAPP Slots. Given the proposed changes to CAPP time line would eliminate legislative oversight of CAPP funding, we recommend rejecting the proposal and continuing to use the current time line, where new CAPP slots are not allocated and CAPP contracts are not finalized until after the Legislature enacts a budget. We also recommend assuming new slots are implemented beginning October 1 and reducing 2024‑25 funding by $46 million General Fund.

Explore Ways CCTR Contract Process Can Be Streamlined to Increase Number of Awarded and Filled Slots. Given the concerns around CCTR contract delays, the Legislature may want to consider ways to streamline the contract process. For example, the Legislature could direct DSS to develop a simplified funding application for existing CCTR providers who have demonstrated success in enrolling and serving subsidized children. Additionally, the Legislature could request the department explore ways to improve coordination across various DSS teams that review and execute final contracts.

Adopt Proposed Funding Levels for Bridge Vouchers and Further Offset General Fund Costs With Carryover Funds. Given that actual Bridge voucher expenditures have been significantly lower than total budgeted levels, state funds alone would likely be more than enough to cover actual Bridge voucher expenditures in 2024‑25. Additionally, to further address the overall budget deficit, we recommend reducing 2023‑24 Bridge voucher costs by $40 million General Fund to reflect the carryover of unspent 2022‑23 funds. The Legislature could also ask the administration to provide a more precise estimate of the anticipated unspent 2023‑24 funds as a part of the May Revision and proactively sweep these funds as additional budget savings.

Consider Adjusting Cost Estimates of Slot Expansion Plan to Reflect More Recent Cost Per Slot Data. In order to effectively estimate the availability of state resources in future years, the Legislature could direct the administration to update the cost estimates of the slot expansion plan based on more recent cost per slot data. This would allow the Legislature to more accurately plan for ongoing costs associated with the child care slot expansion plan, including assessing the capacity of future budgets to support this ongoing cost pressure.

Proposition 64 Funding Levels

Background

State Had a $296 Million Carryover Balance in Child Care Proposition 64 Funds by the End of 2022‑23. Since 2019‑20, an average of $74 million in Proposition 64 funds allocated to child care programs go unspent each year. These Proposition 64 funds went unspent primarily due to slower slot take‑up in the CAPP, CCTR, and Bridge programs. Any unspent funds are carried over into the following fiscal year. The Proposition 64 child care carryover balance as of March 2024 totals $296 million.

Portion of Child Care Carryover Funds Were Intended to Backfill Decline in 2023‑24 Proposition 64 Funding Levels in CCTR Program. As part of the 2022‑23 budget package, the state eliminated the cannabis cultivation tax, which provided roughly one‑fifth of Proposition 64 tax revenue. Recognizing the resulting fiscal risk, the budget package also established a target funding level for programs that receive Proposition 64 revenues (the “2020‑21 baseline”) and included provisions intended to keep funding from falling below that target. For example, the 2022‑23 budget package included $150 million one‑time General Fund—referred to as the 2022‑23 backfill set aside—that the State Controller’s Office could transfer to Proposition 64 programs in 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. Ultimately, 2023‑24 Proposition 64 revenues declined by a greater amount than the total 2022‑23 backfill set aside. As a result, the 2022‑23 backfill set aside could only partially backfill losses in Proposition 64 funds in 2023‑24. In the case of child care, the 2023‑24 budget assumed a $46 million Proposition 64 shortfall in the CCTR program relative to 2020‑21 baseline levels. We understand that as a part of the 2023‑24 budget agreement, the $46 million Proposition 64 shortfall was intended to be filled with Proposition 64 carryover funds.

Governor’s Budget

Continues to Appropriate Proposition 64 Funds to Child Care Programs. The Governor’s budget provides a total of $269.8 million Proposition 64 funds in 2023‑24 and $247 million Proposition 64 funds in 2024‑25. These funds are spread across CAPP ($173.8 million in 2023‑24 and 2024‑25), CCTR ($92.2 million in 2023‑24 and $69.4 million in 2024‑25), and the Bridge program ($3.8 million in 2023‑24 and 2024‑25).

Projects Proposition 64 Carryover Balance Will Total $415.3 Million by the End of 2023‑24. The administration estimates only $150.5 million of the $269.8 million Proposition 64 allocated to child care in 2023‑24 will be spent. The unspent funds will carry forward into 2024‑25, increasing the total carryover balance from $296 million to $415.3 million by the end of 2023‑24. The Governor’s budget does not include a proposal for using this carryover balance.

Does Not Provide Backfill for CCTR Proposition 64 Shortfall in 2023‑24. The Governor’s budget assumes Proposition 64 funding levels in CAPP and the Bridge program remain equal to 2020‑21 baseline levels in 2023‑24. The Governor’s budget, however, assumes Proposition 64 funding levels increase by $23.5 million in 2023‑24 relative to 2023‑24 Budget Act levels—from $68.7 million to $92.2 million. This increase is due to Propositions 64 revenues projected to come in slightly higher than initial 2023‑24 estimates. Despite this increase, Proposition 64 funding levels for the CCTR program in 2023‑24 remain $22.5 million below 2020‑21 baseline levels. This is, in part, because the Governor’s budget does not include the previously agreed upon backfill.

Continues to Assume CCTR Proposition 64 Funding Levels Remain Below 2020‑21 Baseline Levels in 2024‑25. The Governor’s budget assumes Proposition 64 funding levels for CAPP and the Bridge program remain flat between 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. In the CCTR program, however, Proposition 64 levels decrease from $92.2 million in 2023‑24 to $69.4 million in 2024‑25. As a result, Proposition 64 funding levels in the CCTR program remain $45.3 million below 2020‑21 baseline levels in 2024‑25. We understand that the administration does not propose to backfill Proposition 64 funds in 2024‑25.

Assessment and Recommendation

While Proposition 64 Backfill Is Not Needed Under New CCTR Budgeting Methodology… The new budgeting methodology proposed by the Governor reduces total CCTR funding levels to only reflect estimated costs of awarded slots. Additionally, the Governor’s budget assumes any CCTR program costs not offset by federal funds or Proposition 64 funds will be covered with General Fund. As a result, a Proposition 64 backfill is technically not needed to fully fund the CCTR program in 2023‑24 and 2024‑25.

…Legislature Could Consider Working With Administration to Use Proposition 64 Carryover Funds to Further Offset General Fund Costs. Proposition 64 revenues, including carryover funds, are continuously appropriated, meaning that they are allocated by the administration and are not subject to the legislatively driven annual budget process. Proposition 64 carryover funds may be leveraged by the state in various ways. For example, carryover funds could make up for any future declines in Proposition 64 revenues. Alternatively, all or a portion of the Proposition 64 carryover funds could be used to offset General Fund costs in child care programs, resulting in additional one‑time General Fund savings. Given the significant budget shortfall, the Legislature could consider working with the administration to determine if and how much of the Proposition 64 carryover funds could be used to maximize General Fund savings.

Federal Funds Update

Background

State Draws Down Three Different Federal CCDF Dollars. As shown in Figure 9, each type of CCDF dollar has its own obligation and liquidation deadline. Matching and Mandatory funds received through the federal 2023‑24 budget must be obligated by September 30, 2024. Matching funds must be liquidated by September 30, 2025. States have an additional year to obligate and liquidate Discretionary funds. Any CCDF dollars not obligated or liquidated by the appropriate deadlines revert back to the federal government. CCDF dollars are generally considered to be obligated if the dollars are included in the state budget and liquidated once DSS releases funds to providers.

Figure 9

Spending Deadlines for Child Care and Development

Fund Dollars

Federal Fiscal Year 2023‑24

|

CCDF Fund Source |

Obligation Deadline |

Liquidation Deadline |

|

Mandatory |

September 30, 2024 (by the end of first federal fiscal year) |

No requirement to liquidate by a specific date |

|

Matching |

September 30, 2024 (by the end of first federal fiscal year) |

September 30, 2025 (by the end of second federal fiscal year) |

|

Discretionary |

September 30, 2025 (by the end of second federal fiscal year) |

September 30, 2026 (by the end of third federal fiscal year) |

CCDF Rules Require States Spend a Certain Amount of Funding on Quality Improvement Activities. As a condition of receiving CCDF dollars, the federal government requires states use at least 9 percent of total CCDF dollars on general quality improvement activities and at least 3 percent of total CCDF dollars on quality improvement activities specific to infant and toddler child care services. Allowable quality improvement activities include training and professional development opportunities for child care providers; developing and implementing a quality rating system; and supporting child care providers to develop and adopt high‑quality program standards related to health, mental health, cognitive development, and physical activity.

The State Is Still Spending Down Temporary COVID‑19 Federal Relief Funds. During the COVID‑19 pandemic, the state received over $5 billion in one‑time federal funds to support child care programs. About $3.6 billion of the COVID‑19 relief funds expired on September 30, 2023. The administration estimates that DSS obligated and liquated nearly all of these funds by the federal deadline, resulting in less than $1 million in federal relief funds reverting back to the federal government. The department is still in the process of spending down the remaining $1.4 billion in COVID‑19 relief funds, which expire on September 30, 2024.

Governor’s Budget

Continues to Appropriate CCDF Dollars in 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. The Governor’s budget assumes the state will draw down $1.08 billion in CCDF dollars in 2023‑24 and $1.04 billion in CCDF dollars in 2024‑25. The budgeted amounts of CCDF dollars are subject to change based on the redistribution of unobligated funds from other states and anticipated increase to CCDF Discretionary funding levels in 2023‑24 that was recently approved by the federal government in March 2024 (which we describe in more detail below).

Continues to Appropriate Federally Required CCDF Quality Funds. The Governor’s budget sets aside $157 million CCDF dollars in 2023‑24 and 2024‑25 to support quality improvement activities—referred to as CCDF quality funds. We understand that these funding levels reflect the administration’s estimate of the federally required minimum amount of funding that must be spent on quality improvement activities. Based on the 2023‑24 CCDF quality plan, some of the activities that would be funded with the 2023‑24 quality set aside include child care license enforcement, resource and referral agencies, local child care planning councils, and education stipends for child care professionals. DSS is still finalizing the 2024‑25 CCDF quality plan.

Continues to Use One‑Time COVID‑19 Federal Relief Funds to Cover Costs for Slot Increases. As shown in Figure 10, the Governor’s budget continues to obligate most of the remaining $1.4 billion in COVID‑19 relief funds to offset costs associated with the child care slot expansion plan. (The administration has indicated ongoing slot costs previously covered with federal relief funds would shift to the General Fund once the federal funds expire.) The Governor’s budget also obligates a portion of remaining COVID‑19 federal relief funds to support various one‑time or temporary activities, including infrastructure grants and development of a new child care data system.

Figure 10

Distribution of COVID‑19 Federal Relief Funds That

Expire September 30, 2024

(In Millions)

|

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

Total |

|

|

Slot expansion |

$544 |

$779 |

$38 |

$1,361 |

|

Reimbursement flexibilities |

50 |

— |

— |

50 |

|

Infrastructure grant program |

1 |

24 |

— |

25 |

|

Child care data system |

1 |

4 |

— |

5 |

|

CDE after school program |

3 |

— |

— |

3 |

|

Totals |

$599 |

$807 |

$38 |

$1,443 |

|

CDE = California Department of Education. |

||||

Assessment

Governor’s Budget Does Not Fully Obligate All Available CCDF Dollars. We estimate that the state could draw down an additional $99 million in CCDF dollars across 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. A portion of these funds would need to be set aside for quality improvement activities. We describe the reasons for these additional CCDF dollars and quality set aside below.

- Updated Estimates of Available CCDF Dollars Based on Federal Award Notices. Based on actual federal notices of awards and revised estimates, the administration anticipates receiving, on net, an additional $3 million CCDF dollars in 2023‑24 and $38 million CCDF dollars in 2024‑25 relative to Governor’s budget estimates. Some of these funds would need to be obligated by September 30, 2024 to comply with federal obligation deadlines.

- Federal 2024‑25 Budget Increases to CCDF Discretionary Funding Levels. The recently enacted federal 2024‑25 budget included a $725 million increase to CCDF Discretionary levels. We estimate that California would receive $58 million of these additional CCDF Discretionary funds in 2024‑25. These funds would need to be obligated by September 30, 2025 to comply with the federal obligation deadline.

- Increase in Required Amount of CCDF Quality Funds. As a result of the updated estimates of available 2024‑25 CCDF dollars and recently approved increase to total CCDF Discretionary levels, we estimate that the state will need to set aside roughly $10 million in additional CCDF quality funds in 2024‑25 to comply with the federally required minimum amount of funding for quality improvement activities. The remaining CCDF dollars—$89 million—may be used for other child care and development program activities.

Unclear How 2024‑25 CCDF Quality Funds Will Be Used. As previously mentioned, the administration is still in the process of finalizing the list of quality improvement activities that would be supported by CCDF quality funds in 2024‑25. In the past, CCDF quality plans were generally finalized after the Legislature approved the associated funding through the annual budget process.

COVID‑19 Relief Funds Are Being Expended at a Slower Pace Relative to Initial Estimates. The administration assumed about $600 million of the $1.4 billion in COVID‑19 relief funds would have been spent by the end of 2022‑23. However, as of December 31, 2023, only $383 million of the COVID‑19 relief funds have been expended. By the end of 2023‑24, the Governor’s budget assumes only $38 million of COVID‑19 relief funds would remain unexpended. However, we estimate that roughly $450 million of COVID‑19 relief funds may remain unexpended by the end of 2023‑24. The slower than expected expenditures of COVID‑19 federal relief funds are likely due to slower than expected slot take‑up. To the extent expenditure trends continue to come in lower than initial estimates, hundreds of millions of COVID‑19 relief funds would likely revert back to the federal government in 2024‑25.

Recommendations

Direct Administration to Fully Obligate All Available CCDF Dollars as a Part of May Revision. We estimate that the state can draw down an additional $99 million in CCDF dollars across 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. (About $10 million of these funds would need to be spent on quality improvement activities per federal CCDF requirements.) While some of these funds do not need to be obligated until September 30, 2025, we recommend the Legislature direct the administration to obligate all available CCDF dollars as a part of the May Revision in order to maximize the amount of General Fund costs that could be offset in 2024‑25. (The Legislature could revise 2024‑25 CCDF levels next year to the extent actual funding levels are different than initial estimates.)

Require Annual CCDF Quality Plan Be Included in May Revision on an Ongoing Basis. While the Legislature approves the amount of CCDF funds that are set aside for quality improvement activities as a part of every annual budget process, the administration generally does not share with the Legislature how these funds would be used until after the budget is approved. We recommend the Legislature direct the administration to include the proposed CCDF quality plan in the May Revision of every state budget. This would ensure the same level of oversight and input the Legislature exercises over other components of the child care budget.

Direct Administration to Prioritize Spending COVID‑19 Relief Funds to Minimize Federal Reversion and Maximize General Fund Savings. Last year, our office identified about $550 million of COVID‑19 relief funds that were at risk of going unspent by the September 30, 2023 federal deadline. To avoid these funds from reverting back to the federal government, the Legislature worked with the administration to carry over these unspent funds into 2023‑24 and prioritize the use of expiring COVID‑19 relief funds prior to using other fund sources, including the General Fund. This approach had the effect of freeing up an equal amount of General Fund, which the Legislature and administration set aside to support costs associated with the child care MOU and parity agreement.

Similar to last year, we recommend the Legislature request the administration provide an updated May Revision estimate on (1) the total amount of COVID‑19 relief funds (including funds obligated in prior years) that would likely go unspent by the end of 2023‑24, and (2) what amount of these unspent funds could be used to effectively free‑up General Fund in 2024‑25. The Legislature could either score the estimated amount of freed‑up General Fund as budget savings or recommit all or a portion of these funds to other budget priorities. For example, to the extent the child care infrastructure grant program currently funded with temporary COVID‑19 relief funds would not be fully implemented by September 30, 2024, the Legislature could instead fund the program with General Fund and extend the duration of the program.

Child Care MOU and Parity Agreement Update

Background

2023‑24 Budget Adopted a New Two‑Year, Collectively Bargained MOU and Parity Agreement. The MOU agreement provided monthly per‑child cost of care plus supplemental rate payments, a one‑time transitional payment, and temporary extension of reimbursement flexibilities. The state negotiated the MOU agreement with Child Care Providers United (CCPU), which represents licensed family home and license‑exempt family, friend, and neighbor providers. Similar to the first MOU agreement, the state extended the collectively bargained provisions to non‑represented, center‑based child care and State Preschool providers to ensure parity across all early education programs (with the exception of the health, retirement, and training funds, which is limited to CCPU‑represented providers). The collectively bargained and parity agreement provisions are generally set to expire on June 30, 2025. In total, the child care‑related components of the MOU and parity agreement were initially estimated to cost up to $1.2 billion across 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. (These costs do not include costs related to the State Preschool program.)

MOU Agreement Requires Development of Alternative Methodology for Single Child Care and Preschool Rate Structure. The MOU agreement and associated 2023‑24 trailer bill language required DSS, in collaboration with the California Department of Education, to develop and conduct an alternative methodology for a single rate structure. Additionally, the administration was directed to work with the Joint Labor Management Committee (JLMC) to define the elements of the base rates and any enhancement rates for purposes of informing the alternative rate methodology. (The JLMC was created in 2021 to assist in the development of a single reimbursement rate structure.) The alternative methodology would also be informed by a new cost study and cost estimation model. We understand that the cost study and model would consider costs to comply with current program requirements (such as health and safety standards, staffing requirements, and licensing requirements), provide high‑quality care, and provide higher compensation to staff relative to current levels.

Governor’s Budget

Maintains Initial Funding Levels to Support Child Care‑Related MOU and Parity Costs. The 2023‑24 budget included $1.3 billion in one‑time funds from various state and federal fund sources to cover child care costs resulting from the MOU and parity agreement. At the time, the set aside amount exceeded estimated child care‑related MOU and parity costs by $106 million. The Governor’s budget continues to set aside the same amount of funding to cover child care‑related MOU and parity costs.

Continues Progress Towards Developing Alternative Rate Methodology. Per the MOU agreement and associated 2023‑24 trailer bill language, by February 15, 2024, DSS was required to reach agreement with the JLMC on the definitions of base rate elements and any enhanced rates for purposes of informing the single rate structure. On March 6, 2024, the administration and JLMC reached a general consensus on base and enhanced rate definitions. Additionally, the department provided the Legislature with the required report on progress made to conduct an alternative methodology and cost estimate model to inform a future single rate structure for subsidized child care and development services.

Assessment and Recommendation

Consider Reappropriating One‑Time Unspent Funds to Offset Higher Than Expected Child Care MOU and Parity Costs. In June 2023, the administration estimated the child care MOU and parity agreement would cost up to $1.2 billion. Based on more recent data, DSS now estimates that total child care MOU and parity costs would be $1.4 billion, which is $213 million above 2023‑24 Budget Act cost estimates. We anticipate that a portion of these additional costs would be covered with the previously mentioned unobligated MOU and parity set aside funds ($106 million). Beyond the unobligated MOU and parity set aside funds, the state would need to provide an additional $107 million to cover the remaining amount of child care‑related MOU and parity costs. Given the projected budget deficit, the Legislature could reappropriate a portion of the previously identified funds that are projected to go unspent to cover the remaining amount of child care‑related MOU and parity costs not covered by the MOU and parity set aside.

DSS Anticipates Meeting All Future Alternative Methodology Milestones. Even though DSS did not reach an agreement with JLMC on rate element definitions by the required deadline, we understand that DSS anticipates meeting all future milestones. This includes submitting the necessary information to support the use of a single rate structure based on the alternative methodology to the federal government no later than July 1, 2024. We will continue to monitor progress made by DSS to meet future milestones and, if necessary, update the Legislature on any concerns.