Budget and Policy Post

February 23, 2024The 2024‑25 Budget

Judicial Branch

Overview

Roles and Responsibilities. The judicial branch is responsible for the interpretation of law, the protection of people’s rights, the orderly settlement of all legal disputes, and the adjudication of accusations of legal violations. The branch consists of statewide courts (the Supreme Court and Courts of Appeal), trial courts in each of the state’s 58 counties, and statewide entities of the branch (Judicial Council, the Judicial Council Facility Program, and the Habeas Corpus Resource Center). The branch receives support from several funding sources including the state General Fund, civil filing fees, criminal penalties and fines, county maintenance-of-effort payments, and federal grants.

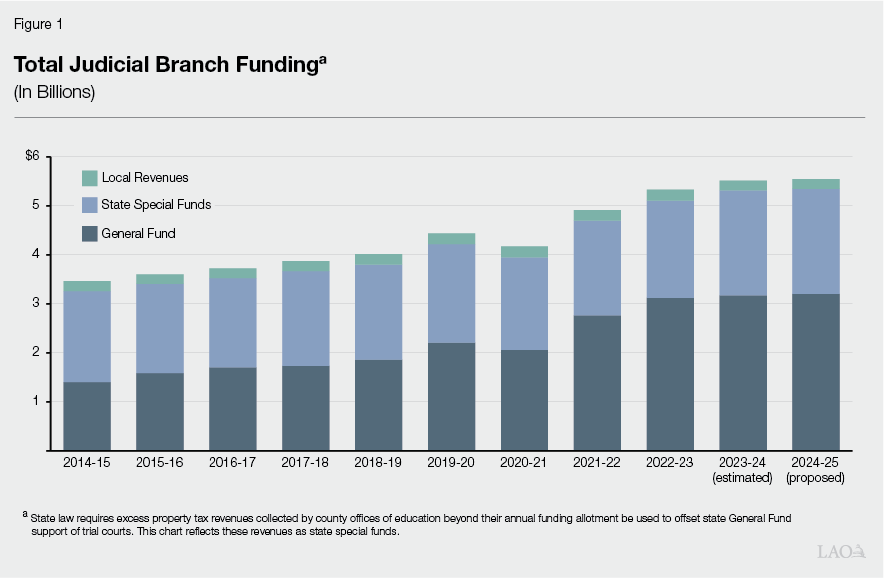

Majority of Support From General Fund. As shown in Figure 1, total operational funding for the judicial branch has steadily increased from 2014‑15 through 2023‑24. The percent of total operational funding from the General Fund has also steadily increased during this period, from 41 percent in 2014‑15 to 58 percent in 2023‑24. Since 2019‑20, the majority of the judicial branch budget has been supported by the General Fund. This growth is generally due to increased operational costs as well as the use of General Fund resources to backfill decreases in fine and fee revenue.

Governor Proposes $5.3 Billion in State Funds for Judicial Branch. For 2024‑25, the Governor’s budget includes $5.5 billion from all fund sources in support for the judicial branch. This amount includes about $5.3 billion from all state funds (General Fund and special funds), a decrease of $31 million (0.6 percent) below the revised amount for 2023‑24, as shown in Figure 2. (These totals do not include expenditures from local reserves or trial court reserves.) Of this amount, about $3.2 billion (63 percent) is from the General Fund. This is a net increase of $30 million (1 percent) from the revised 2023‑24 General Fund amount. This net increase reflects various changes, including increased operational costs.

Figure 2

Judicial Branch Budget Summary—All State Funds

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

Change From 2023‑24 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

State Trial Courts |

$3,749 |

$3,986 |

$4,033 |

$47 |

1.2% |

|

Supreme Court |

49 |

58 |

56 |

‑2 |

‑3.6 |

|

Courts of Appeal |

278 |

290 |

290 |

— |

0.1 |

|

Judicial Council |

284 |

347 |

311 |

‑36 |

‑10.4 |

|

Judicial Branch Facility Program |

728 |

614 |

637 |

23 |

3.7 |

|

Habeas Corpus Resource Center |

17 |

20 |

20 |

— |

‑0.3 |

|

Totals |

$5,105 |

$5,315 |

$5,346 |

$31 |

0.6% |

Trial Courts Report $485 Million in Reserves at End of 2022‑23. Trial courts have a limited ability to keep and carry over any unspent funds (also known as “reserves”) from one fiscal year to the next. Specifically, trial courts are only allowed to carry over funds equal to 3 percent of their operating budget from the prior fiscal year under current law. However, certain funds held in the reserve—such as those that are encumbered, designated for statutorily specified purposes, or funds held on a court’s behalf by Judicial Council for specific projects—are not subject to this cap, meaning they also can generally be carried over. At the end of 2022‑23, trial courts reported having $485 million in reserves. Of this amount, $402 million (83 percent) is not subject to the cap. This amount consists of funds that are encumbered ($157 million), statutorily excluded ($110 million), designated for prepayments or other purposes ($108 million), or held by Judicial Council on behalf of the trial courts for specific projects ($27 million). This leaves $82 million (17 percent) in reserves subject to the cap. This is less than the $97.5 million the trial courts could have retained under the current 3 percent cap. We note the Governor’s 2024‑25 budget proposes increasing the cap to 5 percent or $100,000—whichever is greater—which would allow the courts to retain more in their reserves.

Self-Help Center Funding

Background

Self-Represented People Can Be at a Legal Disadvantage and Increase Court Workload. Self-represented people are those who choose to access certain court services without the assistance of legal counsel—typically related to civil matters. This is generally because they cannot afford to hire legal representation. Given their lack of familiarity with statutory requirements and court procedures (such as what forms must be filled out or their legal obligations in the potential case), self-represented people can be at a legal disadvantage. In addition, trial court staff tend to spend significantly more time processing a self-represented filing than one with legal representation. For example, a self-represented litigant who files incomplete or inaccurate paperwork can lead to the litigant having to file paperwork repeatedly, the court having to continue or delay cases, or the court needing to schedule additional hearings.

Various Legal Resources Supported by State Funds. To help self-represented people access the court system, the state provides tens of millions of dollars annually to support various legal resources. These legal resources are provided by the judicial branch, legal stakeholders (such as county law libraries or legal aid organizations), and partnerships between trial courts and legal stakeholders. (We note that such legal resources may also be supported by federal or other non-state funds.) These legal resources generally fall into two categories: (1) legal assistance and (2) legal services.

Legal Assistance. Legal assistance generally refers to programs and services which provide assistance with navigating the court system—such as providing access to legal publications or assistance in the completion of legal forms. However, no legal advice or representation is provided. Major judicial branch legal assistance programs include self-help centers (discussed in more detail below) located in each of the 58 trial courts. It also includes a statewide web portal to allow self-represented people to research, complete, and file forms electronically, as well as to track their cases online. Interactive instructional tools and chat functions built into the system provide litigants with assistance in completing forms, addressing questions, or prompting next steps. In addition to the judicial branch, other legal stakeholders may also provide legal assistance. For example, county law libraries—generally supported by a share of civil filing fees—provide free access to legal books and publications to county residents, State Bar members, and certain governmental officials. These libraries may also offer legal assistance with forms, offer classes and workshops, and facilitate obtaining advice from attorneys.

Legal Services. Legal services generally refer to those programs and services which may provide legal advice and representation, in addition to legal information. Two key examples are the Shriver Program and the state Equal Access Fund (EAF) Program. First, the Shriver Program—supported by a share of certain post-judgement civil filing fees—provides competitive grants to support projects in which a court partners with a legal services provider to provide legal representation to low-income people in civil matters that affect basic human needs (such as housing, child custody, probate, and conservatorship matters). Services are limited to those whose household income are at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty level. Currently, the Shriver Program supports 14 projects at 11 courts. Second, the EAF Program provides grants to more than 100 legal services providers (such as Legal Aid) across the state to support legal services or assistance to low-income or self-represented people. Funding may be provided for discretionary use or for specific purposes (such as specifically for housing-related issues). For discretionary monies, 90 percent generally supports free civil legal services for low-income people whose income is at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty level or who are eligible for certain federal benefits. The remaining 10 percent supports partnerships in which a provider partners with local courts to provide legal assistance to self-represented people (such as self-help centers).

Wide Range of Assistance Provided by Self-Help Centers. Each of California’s trial courts operates a self-help center which serves as a central location for self-represented people to educate themselves and seek assistance with navigating court procedures. Attorneys and other trained personnel who staff the centers provide services in a variety of ways (such as through one-on-one discussions, workshops, and referrals to other legal resources). This assistance is provided for issue areas ranging from divorce and child custody to small claims. Individual self-help centers use their own resources but may also utilize certain statewide resources and services provided by Judicial Council, such as electronic document assembly programs that populate court forms based on self-represented peoples’ answers to certain questions. We note that self-help centers could also utilize self-help services provided by other governmental, nonprofit, or private organizations as well.

Funding for Self Help in Recent Budgets. Specifically related to self-help centers, the 2018‑19 budget provided $19 million General Fund annually for three years to supplement $11 million in existing support from the Trial Court Trust Fund (TCTF, $6.2 million) and Improvement and Modernization Fund ($5 million). This increased the total annual direct funding for self-help centers to $30 million through 2020‑21. The 2021‑22 budget then extended this increased funding level for an additional three years. These funds are allocated to individual centers using a formula based on the population of the county where the center is located. Self-help centers also can receive funding from other sources, such as trial court operation dollars and federal funds.

Funding for Other Legal Resources in Recent Budgets. In addition to the above funding provided directly for self-help centers for use at the judicial branch’s discretion, the state has also provided funding for other programs in recent years to maintain or increase levels of legal resources provided to the public. Key examples include:

Community Assistance, Recovery, and Empowerment (CARE) Program. The CARE Program is a new civil court proceeding that allows specific people to seek assistance for certain adults with severe mental illness. Upon full implementation, the 2023‑24 budget includes $75 million in ongoing General Fund support, including $10.6 million for attorneys to provide legal assistance related to the CARE program and $64.4 million for legal services providers (or county public defender offices) to provide legal representation related to the program.

Statewide Web Portal. As noted above, the judicial branch currently maintains a statewide web portal to help self-represented people navigate the court system. The 2018‑19 budget included $3.2 million General Fund in 2018‑19, declining to $709,000 annually beginning in 2020‑21, to construct and maintain this web portal.

County Law Libraries. To address declines in the amount of civil filing fee revenues available to support county law libraries, four budgets have included one-time General Fund assistance to help maintain service levels. Specifically, this includes $17 million in 2018‑19, $7 million in 2020‑21, $17 million in 2021‑22, and $17 million in 2022‑23.

Shriver Program. The 2020‑21 budget included $11 million in ongoing funding from the TCTF to reflect the additional amount of revenue available to support the program after Chapter 217 of 2019 (AB 330, Gabriel) increased the amount of certain post-judgement civil filing fees that are available to support the program.

EAF Program. The 2021‑22 budget included an ongoing $15 million General Fund augmentation to provide discretionary funding for the program. Additionally, the 2022‑23 budget included $45 million in one-time General Fund support for eviction-related matters ($30 million) and consumer debt-related issues stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic ($15 million).

Governor’s Proposal

$19 Million Ongoing General Fund to Maintain Self Help Center Funding. The Governor’s 2024‑25 budget proposes to provide a $19 million ongoing General Fund augmentation for self-help centers. As absent this proposal direct state funding for self-help centers would decrease to $11 million beginning in 2024‑25, this proposal represents a budget augmentation. However, if approved, this proposed augmentation would maintain direct state funding for self-help centers at $30 million—the level it has been at since 2018‑19.

Assessment

Proposed Self Help Funding Would Maintain Increased Service Levels. Given the state’s budget problem, any discretionary proposal—including this proposal—seeking to increase General Fund support in 2024‑25 and future years merits additional scrutiny. This proposal technically increases General Fund support on an ongoing basis. However, this is necessary to maintain the increased level of funding that has been provided for self-help services since 2018‑19, which has allowed self-help centers to serve approximately 600,000 people. Absent a continuation of this funding, self-help center service levels would decrease.

Proposed Self-Help Funding Would Help Promote Equity. Additionally, funding for self-help centers helps promote equity. People seeking self-help center services generally are lower-income and cannot afford the services of an attorney to address issues that may have significant impacts on their lives—such as divorce, child custody, domestic violence, eviction, and guardianship issues. While some of these people may be low-income enough to obtain free legal representation (such as through the Shriver Program or EAF Program), a number of them will not be eligible because the income threshold that must be met to qualify for those programs is quite low. This puts them at a legal disadvantage compared to those who receive representation or legal advice, as they do not have the legal knowledge or expertise to know how to navigate courts processes. For example, such people may have difficulty identifying, completing, and serving the necessary forms and documents to initiate a case or to respond to an attorney’s filing. Moreover, such people are also less likely to be able to afford to come back to court repeatedly—such as if their case has to be refiled or continued due to inaccurate completion of forms or a lack of knowledge about how to navigate court processes. Self-help centers can help mitigate such obstacles, which increases the ability of these people to successfully access the courts on a more equal footing with those who are represented by lawyers.

Cost Benefit Evaluation Found Some Self-Help Services Created Net Benefits. As directed by the Legislature, the judicial branch completed a cost-benefit analysis of self-help centers in June 2022. The analysis measured benefits to the courts as the cost-savings estimated to be generated by self-help centers, such as savings from reduced judicial and staff time needed due to more efficient and fewer court interactions. The analysis measured benefits to litigants as the money they saved as a result of using self-help centers, such as wages they would have otherwise lost from having to travel to court unnecessarily. The analysis measured costs as the cost to the courts of providing the self-help assistance. The analysis found that providing self-help in family, civil, and probate cases were net beneficial to both the courts and litigants. This means the benefits to the courts and litigants outweighed the costs of providing the self-help center services. For example, as shown in Figure 3, the analysis found that a civil case which received self-help one-on-one assistance resulted in $322 in benefits and $89 in costs—resulting in net benefits of $233 per filing. For civil cases which received self-help assistance through a workshop, the net benefit was $267 per filing.

Figure 3

Summary of Judicial Council Cost‑Benefit Analysis Findings

|

One‑on‑One Assistance |

Workshops |

||||||

|

Benefit |

Cost |

Net Benefit |

Benefit |

Cost |

Net Benefit |

||

|

Civil |

$322 |

$89 |

$233 |

$322 |

$55 |

$267 |

|

|

Family |

322 |

97 |

225 |

322 |

78 |

244 |

|

|

Probate |

322 |

172 |

150 |

322 |

107 |

215 |

|

Evaluation of Shriver Program Showed it Produced Notable Benefits Over Self Representation. A June 2020 statutorily required evaluation of the Shriver Program found that legal representation generated different benefits than self-help centers. For example, in comparing eviction cases in which low-income tenants were represented through Shriver projects with those who were self-represented, the evaluation found notable additional benefits for tenants represented by Shriver project attorneys. The evaluation found that tenants served by the Shriver projects were more likely to participate in their case, more likely to have their case resolved by settlement rather than trial, and reduced the level of court involvement. While most tenants still ultimately moved, few tenants served by the Shriver projects were ultimately formally evicted—which would have impacted their ability to seek replacement housing. Additionally, in comparison to self-represented tenants, Shriver project attorneys were able to help reduce the amount of money their tenant clients ultimately had to pay to resolve their cases and to obtain terms to benefit their clients’ credit (such as not reporting the case to credit agencies). This made it more likely that Shriver clients found replacement housing within a year.

Evaluations Show That Different Benefits Achievable Based on What Legal Resources Are Funded. Both evaluations demonstrated that self-help centers and the Shriver Program generated benefits, and thus could merit funding consideration. However, the different benefits generated raises policy considerations for the Legislature regarding where funding should be invested to generate legislatively desired results. For example, the Shriver Program evaluation demonstrates that legal representation for low-income tenants can have a meaningful impact on their ability to obtain replacement housing relatively quickly—which could reduce the chance they become homeless. If the Legislature determined the benefits of the Shriver Programs were policy priorities, it could provide funding to prioritize expanding legal representation to tenants to the 47 courts that currently lack the Shriver Program or expanding the number of people who would be eligible for services. In contrast, if the Legislature prioritized court operational efficiency by reducing delays from incomplete forms or lack of procedural knowledge, it would be preferable to invest in self-help centers, which can reduce court operational costs.

State Lacks Strategic Plan For Legal Resources Funding. The state currently lacks a plan for how to strategically approach funding for legal resources broadly. This is because funding for the array of legal assistance and service programs supported by the state has generally been considered on a piecemeal basis based on the needs of each individual program. This means that decisions about legal resources funding have not been made holistically with a view to strategically maximizing their impact. Specifically, the different programs have not been compared against one another to see which have the greatest impact, what populations are being served by each program, where programs may overlap, where there may be gaps in services. For example, self-help centers, law libraries, and legal services providers (who may also receive federal and other funds) may provide workshops on certain topics. However, it is not clear the extent to which the workshops may cover the same topics and serve the same population. Nor is it clear whether greater impact and efficiency could be achieved by consolidating responsibility for certain workshops with specific providers.

Strategic Plan for Funding Is Important Due to Large, Potentially Growing, Unmet Need. Strategic use of any funding provided to support legal resources is particularly important as the estimated need for legal resources already exceeds the current level of resources provided by the state. For example, a 2017 survey of trial courts estimated that an additional $63 million in funding—above the existing $11 million in baseline support—would be needed to fully staff self-help centers. Additionally, the Shriver program is currently only available at 11 courts. Moreover, this mismatch between estimates of the potential need for these resources and the funding available could widen going forward for various reasons. For example, legislation can increase the need and/or reduce the funding available for the support of legal resources. This is the case with Chapter 861 of 2023 (SB 71, Umberg), which increases the small claims case threshold from $10,000 to $12,500 and the limited civil threshold from $25,000 to $35,000. These changes could impact the number of people seeking self-help assistance as individuals are required to represent themselves in small claims proceedings and may be more likely to do so in limited civil cases as well. These changes could also reduce the amount of civil filing fee revenue available to support county law libraries as there may be fewer relevant fees that will be charged. Both of these changes could increase the unmet need for legal resources.

Strategic Plan for Funding Could Improve Service Levels. Given that a significant number of people can benefit from legal assistance and services, it is important that the state maximizes effective use of funding for these legal resources. Maximizing effective use includes strategically determining where money should be placed to achieve the greatest legislatively desired results, to provide people with the resources they most need, and to provide service in the most cost-effective ways possible. For example, the judicial branch’s cost-benefit analysis indicated that workshops provide more net benefits than one-on-one assistance. While one-on-one assistance may be preferred by some people and may be more appropriate in certain complicated cases, it could be cost-effective to strategically maximize the number of workshops offered to address the basics around certain case types. This could help address the basic legal needs of more people, while freeing up attorney time to provide more one-on-one assistance in cases which may be more complicated. Additionally, the state could consider whether more self-help services could be shifted online—and potentially more robustly coordinated across courts, or even the state—to deliver more services at lower costs or at greater frequency than may currently be provided within individual counties. This could similarly increase service levels by providing greater access to more people who may need assistance.

Strategic Plan for Funding Particularly Important Given State Budget Condition. Our office is projecting that the state will face significant fiscal difficulties in both the budget year and future years. As a result, additional funding to expand legal resources may not be available for several years. This would mean that existing funding needs to be more strategically allocated and used if the state would like to address more of the unmet need for legal resources. Alternatively, if the Legislature decides to increase funding for legal resources, it would likely have to come at the expense of other state programs. Under this scenario, it would be equally important that the funding is allocated strategically to ensure the state maximizes the number of people receiving legal assistance or service and/or the quality of the assistance or service provided. Moreover, if the state’s budget situation deteriorates further or if there are more pressing state priorities or needs, the state or other entities that support legal resources (such as Legal Aid) might find it necessary to reduce funding for legal resources now or in the future. To the extent this occurs, strategically maximizing the allocation of the remaining funding would be critical to limiting the impact of such funding reductions.

Recommendations

Direct Judicial Council to Convene Working Group to Provide a Report Assessing Legal Resources. We recommend the Legislature direct Judicial Council to convene a working group to assess the legal resources available in the state. The working group would consist of diverse representatives from the courts (such as judges and self-help staff) and the legal service provider community to represent the different ways in which legal services are provided as well as the different legal resource needs across the state. The working group would review all programs providing legal assistance or services in the state—whether or not they receive state funding—and prepare a report for the Legislature by January 1, 2027. This report would identify what resources are being provided and by which providers, who is eligible for the resources, how resources are provided, the costs of providing such resources, what benefits are generated, and all funding sources available to support such resources. This would provide a comprehensive picture of how legal resources are currently being provided. It would also provide information on where there may be gaps in legal resources and where resources may need to be adjusted or coordinated to prevent duplication.

Direct Working Group to Develop a Strategic Plan for Legal Resource Funding. We recommend the Legislature also require the working group to develop a strategic plan for legal resource funding. Specifically, based on the information in the report recommended above, the strategic plan would detail how to improve the allocation of existing funding to maximize the number of people served and achieve the greatest benefits, minimize the effect of any funding reductions, and identify priorities for where additional funding—should it be available—could be allocated to increase service levels in a cost-effective manner. This strategic plan—as well as the work leading up to it—will help the Legislature weigh funding for legal resources against its other policy and funding priorities and determine how to ensure whatever funding is available for legal resources is used to maximum effect. The working group’s strategic plan for funding should be submitted to the Legislature by January 1, 2027 to provide the Legislature with sufficient time to consider this information to inform its 2027‑28 budget decisions.

Consider Providing Proposed $19 Million in Self-Help Funding for Three-Years. Given the state is currently facing a budget problem, the Legislature will need to weigh the $19 million proposed for continued funding for self-help centers against its other spending priorities. This is because the Legislature will likely need to offset the requested funding for this proposal with spending reductions elsewhere in the budget. If the state’s budget problem worsens, as our recent update to the state budget deficit recently indicated, the Legislature may need to make even more reductions to existing programs and services. This can result in heightened trade-offs to fund this proposal and would therefore require heightened legislative scrutiny on whether this proposal should be approved. However, when evaluating this proposal on its individual merits, we find it reasonable to approve the Governor’s proposal as it would maintain existing funding levels for self-help center and avoid reductions in service levels. Maintaining such service levels benefits both the state and litigants, including making it easier for self-represented people access the courts. However, we recommend only providing the requested funding for three years. This is because this time period would allow Judicial Council to convene the recommended working group and to facilitate the development of a strategic plan. The Legislature would then be able to determine how much funding should be provided beginning in the 2027‑28 budget year to support self-help centers, as well as other legal resource programs, on an ongoing basis using the information in the assessment report and recommendations included in the strategic plan.