LAO Contacts

May 30, 2018

MOU Fiscal Analysis:

Bargaining Unit 6 (Corrections)

On May 18, 2018, the administration released a proposed labor agreement between the state and Bargaining Unit 6 (corrections). Compensation costs for Unit 6 members and their managers constitute more than one-third of the state’s General Fund state employee compensation costs. This analysis of the proposed agreement fulfills our statutory requirement under Section 19829.5 of the Government Code. State Bargaining Unit 6’s current members are represented by the California Correctional Peace Officers Association (CCPOA). The administration has posted the agreement and a summary of the agreement on the California Department of Human Resources’ (CalHR’s) website. (Our State Workforce webpages include background information on the collective bargaining process, a description of this and other bargaining units, and our analyses of agreements proposed in the past.)

The proposed agreement would be in effect for one year. We recommend that the Legislature consider this agreement in the broader context of the state budget because the agreement (1) has significant short- and long-term fiscal implications for the state and (2) interacts directly with budget requests currently pending approval by the Legislature.

Major Provisions of Proposed Agreement

Term. The agreement would be in effect for one year—from July 3, 2018 to July 2, 2019. This is an unusually short term for a Unit 6 agreement. However, it is consistent with our 2007 recommendation to the Legislature not to approve any proposed labor agreements with a term of more than two years.

Five Percent General Salary Increase (GSI) in 2019‑20. Under the agreement, all Unit 6 members would receive a 5 percent pay increase on July 1, 2019. Since furloughs ended in 2012‑13, Unit 6 members have received GSIs in five of the past six fiscal years (see Figure 1). In addition, Unit 6 members are scheduled to receive a GSI in 2018‑19. The MOUs that provided these past and scheduled pay increases also contained concessions from employees including (1) less generous health benefits, (2) increased employee contributions towards pension benefits, (3) a new employee contribution to prefund retiree health benefits, and (3) reduced pension and retiree health benefits for future employees. The agreement now before the Legislature seems to provide the 5 percent pay increase without additional concessions from employees.

Figure 1

General Salary Increases (GSIs) Since End of Furloughsa

|

Approved |

|

|

2013‑14 |

3% or 4%b |

|

2014‑15 |

4 |

|

2015‑16 |

3c |

|

2016‑17 |

— |

|

2017‑18 |

3 |

|

2018‑19 |

3 |

|

Proposed |

|

|

2019‑20 |

5 |

|

aEmployees were furloughed over five fiscal years between 2008‑09 and 2012‑13. Unit 6 member pay was reduced. The pay reduction varied over the course of the furlough period, such that Unit 6 member pay was reduced, depending on the month, anywhere between 5 percent and 14 percent. bEmployees at top step of salary ranges received different pay increase depending on retirement benefits. cGSI of January 2015. |

|

Health Benefits. The state contributes a flat dollar amount to Unit 6 members’ health benefits that was last updated in January 2018. The proposed agreement would adjust the amount of money the state pays toward these benefits in January 2019. Under the agreement, the state’s contribution would be adjusted so that the state pays a dollar amount equivalent to 80 percent of an average of California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) premium costs plus 80 percent of average CalPERS premium costs for enrolled family members—equivalent to what is referred to as the “80/80 formula,” the most common state contribution towards state employee health benefits. The state’s contribution for Unit 6 members’ health premiums would not be increased to reflect 2020 health premiums unless agreed to in a future agreement.

Leave Cash Out. The current agreement permits—to the extent departmental resources allow—Unit 6 members to cash out up to 80 hours of vacation or annual leave each year on or before May 1. Leave is cashed out based on employees’ current hourly pay rate and is subject to Medicare payroll taxes but does not affect employees’ pension benefits. To date, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) has always determined that there were insufficient resources to offer a leave cash out. In addition to the May 1 cash out, the proposed agreement would allow Unit 6 members a one-time opportunity to cash out up to 80 hours of “compensable leave.” (Compensable leave is leave time that can be cashed out and includes, primarily, vacation, annual leave, and holiday and overtime credit. Compensable leave does not include sick leave.) In addition to allowing for more types of leave to be cashed out, the new cash out opportunity differs from the May 1 cash out because it is not dependent on the availability of departmental resources. The agreement specifies that employees “shall be eligible for a one-time cash out of up to 80 hours of compensable leave”

Uniform Allowance. Nearly 90 percent of Unit 6 members are required to wear a uniform while at work. These employees receive annual uniform allowances of $950 in the case of correctional officers and $546 in the case of medical technical assistants. (In the case of correctional officers, the administration indicates that uniforms can cost between $850 and $1,500, depending on the officer’s assignment.) These allowances do not affect employees’ pension or other salary-driven benefits. The proposed agreement would increase these uniform allowances so that both correctional officers and medical technical assistants receive $1,000 each year. The proposed agreement also would allow correctional officers and medical technical assistants to receive the allowance sooner than the current agreement by making them eligible for the allowance upon completing their respective academy instead of upon completing their 12‑month probationary period (as is required by the current agreement). In addition, the proposed agreement would provide a new annual uniform allowance of $250 to about 1,400 parole agents. According to the CDCR Department Operations Manual, “no uniform is required to be worn by parole agents.”

Hourly Pay Increases for Specified Shifts. Unit 6 members receive additional pay for hours they work on night shifts (defined as working more than four hours between 6:00 p.m. and 6:00 a.m.) and weekend shifts (defined as working more than four hours between midnight Friday and midnight Sunday). The proposed agreement would increase these hourly pay differentials by $0.15 per hour. The night shift differential would increase from $0.50 per hour to $0.65 per hour and the weekend shift differential would increase from $0.65 per hour to $0.80 per hour.

Reimbursements for Work-Related Costs. The agreement ties lodging and travel reimbursement rates for Unit 6 members to the rates established in CalHR’s Online HR Manual (refer to Sections 2201, 2202, and 2203). This results in higher reimbursement rates for travel in five counties as well as an increased reimbursement rate for the use of private aircraft. In addition, the proposed agreement increases the reimbursement available to certain employees who participate in a vanpool. Under the current MOU, the primary driver of the vanpool receives $100 per month. The agreement would provide this reimbursement—on a prorated basis—to secondary drivers who drive on days the primary vanpool driver does not work.

Correctional Counselor Time. Employees in the “Correctional Counselor I” classification work 41-hour weeks. The proposed agreement specifies that—effective July 1, 2019—40 hours per week are for regular duty and 1 hour per week is for “pre and post work activities.” The administration’s cost estimates refer to this one hour of time as “walk time.”

Smart Phones for Transportation Teams. The current agreement specifies that vehicles dedicated for transporting inmates shall contain a radio or cell phone capable of communicating with California Highway Patrol. The proposed agreement would require CDCR to “ensure that each transportation team shall be equipped with a state-issued smart phone.”

Parole Agent Caseloads. Parole agent staffing levels and workload are determined based on caseload ratios. In the case of parole agents who supervise sex offenders on parole, caseloads are limited by whether the parole agent supervises high-risk or non-high-risk sex offenders. Under the current system, a parole agent’s caseload cannot exceed 20 high-risk sex offenders or 40 non-high-risk sex offenders (see Figure 2 on page 15 of the pdf of a 2014 Office of the Inspector General Report for more detailed information). The proposed agreement would limit the number of high-risk or non-high-risk sex offenders on a parole agent’s caseload to 25.

Training. Two provisions in the proposed agreement related to training programs specify action in the event that the Legislature appropriates additional funds for training. Specifically, should the Legislature appropriate funds for training, (1) training at the academy would increase from 12 to 13 weeks and (2) the union and state would meet to modify the existing minimum 52 hours of annual training provided to Unit 6 members.

Video Surveillance. The proposed agreement prohibits management from reviewing or viewing live or recorded video for the purpose of routine supervision of staff. However, the agreement specifies that “if during the legitimate review of audio/video, staff misconduct is identified, the audio/video recording can be used as part of the corrective action and/or disciplinary process.” The agreement also specifies that—before a video or audio recording is released pursuant to a Public Records Act request, Unit 6 members who are easily identified in the recording will be notified in writing.

LAO Assessment

Administration’s Fiscal Estimate

2018-19 Costs Mostly Attributable to Leave Cash Outs. As shown in Figure 2, the administration estimates that the proposed agreement will increase state costs for rank-and-file employees represented by CCPOA by $116 million in 2018-19. (The administration assumes that CDCR will pay for about $1.5 million of these costs using existing resources.) About 84 percent of the identified costs in 2018-19 are attributed to employees cashing out 80 hours of leave in September.

Figure 2

Administration’s Fiscal Estimates of Proposed Unit 6 Agreement

(In Millions)

|

Proposal |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

|||

|

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

||

|

2019‑20 general salary increase |

— |

— |

$188.4 |

$192.1 |

|

|

2018‑19 leave cash out |

$95.3 |

$97.1 |

— |

— |

|

|

Health benefits |

9.3 |

9.5 |

15.9 |

16.2 |

|

|

Hourly pay increases for specified shifts |

6.2 |

6.3 |

6.2 |

6.3 |

|

|

Correctional counselor hoursa |

— |

— |

4.3 |

4.4 |

|

|

Uniform allowancea |

3.1 |

3.2 |

3.1 |

3.2 |

|

|

Business‑related reimbursements or paymentsa,b |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

|

Totals |

$113.9 |

$116.1 |

$217.9 |

$222.2 |

|

|

aThe administration assumes some or all of these costs are paid using existing resources. bCosts less than $50,000 round to “0.0.” |

|||||

Omits Some Costs Resulting From GSI in 2019-20. The administration’s estimated cost resulting from the 5 percent GSI in 2019-20 does not take into consideration the full effect of increasing salaries. After taking into account the issues described below, we estimate that the state’s costs beginning in 2019-20 could be tens of millions of dollars above what the administration estimates—virtually all from the General Fund.

Overtime. Overtime constitutes a significant source of income for Unit 6 members. In 2017, rank-and-file Unit 6 members received more than $361 million in overtime payments—this constitutes more than 15 percent of Unit 6 salary cost. Overtime is calculated based on an employee’s regular hourly pay rate—most commonly calculated to be 1.5 times regular pay. It is difficult to forecast overtime utilization; however, we estimate that the 5 percent GSI will increase overtime costs beginning in 2019-20 by at least $6 million, possibly as much as $20 million.

Pension Contribution Rates. Based on the contribution rates approved by the CalPERS board at its April 17, 2018 meeting, the state’s contribution rates to Unit 6 pensions are projected to increase to 48.4 percent of pay by 2019-20 (these rates include the projected actuarially required contributions and the additional contribution the state pays pursuant to state law). The administration’s estimate above does not take into consideration projected growth in the state’s contribution rate in 2019-20. We estimate that state costs beginning in 2019-20 could be more than $3.5 million more than reflected above when assuming current projected pension contribution rates.

Other Post-Employment Benefits (OPEB) Prefunding Contributions. The administration’s estimated fiscal effect of the 5 percent GSI assumes that the state contributes 2.6 percent of that increased salary to prefund retiree health benefits. Per current law—and the proposed agreement—the state is scheduled to pay 4 percent of pay beginning July 2018. Paying the full 4 percent OPEB prefunding increases state costs beginning in 2019-20 by about $1.5 million relative to what is displayed above.

No Cost Attributed to Parole Agent Caseloads. The administration attributes no cost to the changes in parole agent sex offender caseloads. To the extent that there are costs, the administration indicates that CDCR currently has sufficient resources to accommodate the change. We think the provision could increase state overtime or personnel costs. Any effect likely would be in the low millions.

Interactions With Pending Budget Proposals

As discussed below, the proposed agreement interacts with a number of budget proposals currently being considered by the Legislature.

Item 9800. The Governor’s May Revision—submitted to the Legislature before the proposed agreement was finalized—increases Item 9800 in 2018-19 by $112 million General Fund to pay for increased compensation costs for rank-and-file employees represented by CCPOA resulting from a possible agreement with the union. (The item assumes an additional $27 million General Fund to pay for increased costs for associated managers and supervisors.) Based on the cost estimates of the proposed agreement, most of these requested funds appear to be to pay for September 2018 leave cash outs. The administration assumes that all eligible employees cash out 80 hours of leave. This likely is an overestimate of the amount of leave that would be cashed out in September. (The administration indicates that any unspent money would revert to the General Fund.) However, it is important to note that the administration asserts that the Legislature would be rejecting the proposed agreement if it were to reduce or eliminate the requested funding for leave cash outs under Item 9800.

Transportation Team Communication Devices. As part of a request to replace existing public safety radio systems across various facilities, the administration requests funding to replace radio systems used by transportation teams to improve internal and external services and to enable radio interoperability with other first responders. The administration indicates that transportation teams often travel through areas with weak or no cell service, and the new radio system would allow them to communicate while in these more remote areas. In addition to this budget request, the agreement would require the state to provide smart phones to transportation teams. The administration indicates that cell phones and radios serve complementary, not substitute, functions. For example, cell phones allow transportation teams to communicate with institutional staff while radios allow them to communicate with other law enforcement. According to the administration, smart phones provide mapping services and other information storage functions that are useful to transportation teams. The administration indicates that CDCR would use existing resources to make any smart phone purchases required by the agreement.

Overtime Costs. The administration requests $16.5 million General Fund in 2018-19 and ongoing for CDCR to pay for rising overtime costs resulting from past Unit 6 salary increases. The last adjustment that CDCR received to its overtime budget was in 2014-15. Although it is difficult to assess how much overtime CDCR will incur in any given year, the request assumes that 2.6 million hours of overtime are used in a typical year. The request takes into consideration the 3 percent pay increase provided to Unit 6 employees in 2018-19 under the current agreement but does not take into consideration the 2019-20 pay increases included in the proposed agreement. As discussed before, the administration’s fiscal estimate for the agreement does not attribute any increased overtime costs to the agreement. This budgetary request makes it clear that it is difficult for CDCR to use existing resources to pay for rising overtime costs resulting from salary increases agreed to in MOUs.

Correctional Counselors. The administration proposes adjusting the ratio of offenders to Correctional Counselors I so that each counselor’s caseload has 10 percent fewer offenders. The existing ratio has been in place for the past 30 years. In order to implement this ratio reduction, the administration requests $13.5 million and 89 positions. (We recommended the Legislature reject this proposal because CDCR did not fully demonstrate the need to reduce correctional counselor caseloads.) In its estimate of the proposed agreement’s fiscal effect shown in Figure 2, the administration indicates that the value of the one hour of correctional counselor time that would be used for walk time is more than $4 million. This estimate is based on current staffing levels—assuming 967 correctional counselors—and assumes that CDCR will pay for these costs using existing resources. The value of this hour for the 89 requested positions would increase CDCR costs by about $400,000 in 2019-20. It is not clear if reducing the amount of time correctional counselors work by one hour each week would result in CDCR requesting additional resources in the future.

Training. The administration requests funding and positions to add training for peace officer and supervisory positions at CDCR. If the Legislature approves this request, the agreement would (1) require CCPOA and the state to meet to modify the existing 52 hours of annual training and (2) extend the 12-week academy to a 13-week academy.

Video Surveillance. The proposed agreement’s provision limiting the use of audio/video surveillance of employees is relevant to a request for 2018-19 and a request last year for 2017-18 that are part of the administration’s effort to implement a recommendation from the Inspector General that CDCR install cameras in all inmate areas to reduce violent incidents, deter contraband, and prevent suicides and other problematic issues.

Leave Cash Outs

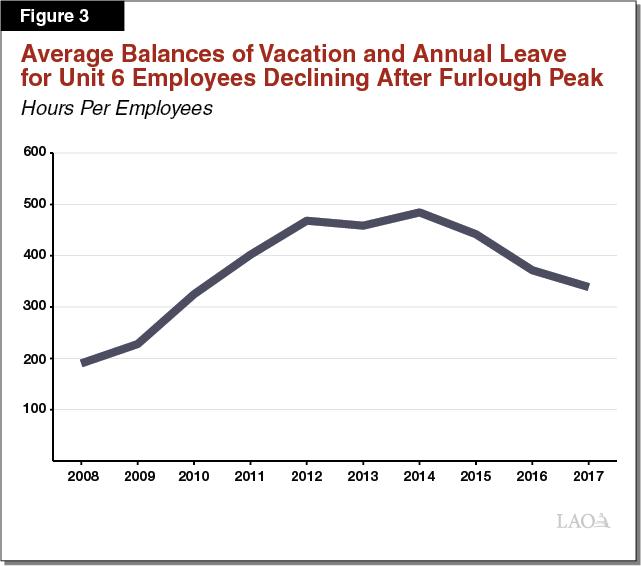

Leave Cash Outs Reduce Long-Term Liability. The average state employee earns a significant number of days off each year. In recent years, the state has made efforts to encourage employees to use more leave. Most Unit 6 members work in 24-hour facilities where it can be difficult for employees to take time off. During the five years of furloughs from 2008-09 to 2012-13, it was virtually impossible for Unit 6 members to use the 94 furlough days they received plus the vacation or annual leave they earned throughout the year. As Figure 3 shows, the result of these furloughs was that the average Unit 6 member’s vacation/annual leave balance more than doubled between 2008 and 2013. In recent years, these balances have started to decrease—likely due to senior employees with large leave balances retiring.

As we explain in our March 14, 2013 report After Furloughs: State Workers’ Leave Balances, unused leave balances create a liability for the state because the state must compensate employees for any unused leave—at their final pay rate—when the employee separates from state service. Employees typically earn their highest salary during their last year of service with the state. We estimate that the total value of Unit 6 members’ unused vacation and annual leave currently is more than $440 million and will grow to more than $460 million after the proposed GSI. Offering cash out programs in which employees can cash out unused leave at their current pay level will reduce the state’s long-term costs associated with these liabilities.

Pay Increase

5 Percent Is a Large Pay Increase. The proposed 5 percent GSI would be the largest given to Unit 6 members since 2006-07. (The MOU that was in place from 2001 to 2006 provided very large pay increases to Unit 6 members, compounding to a 34 percent pay increase over the four fiscal years between 2003-04 and 2006-07.) An employee who is at the top step of his or her salary range will receive a 5 percent pay increase as a result of the proposed agreement. (About two-thirds of Unit 6 members are at the top step of their salary range.) A typical employee who is not at the top step, however, will receive more than a 10 percent pay increase because he or she would receive the 5 percent GSI plus a 5 percent merit salary adjustment.

Administration Has Weak Justification for Large Pay Increase. The administration asserts that the size of the 2019-20 pay increase is not large when compared to 5 percent pay increases that were provided in recent MOUs between the state and Bargaining Units 2, 9, and 10. These other three bargaining units, however, represent the state’s attorneys, professional engineers, and professional scientists. Our understanding is that the 5 percent GSIs for these three groups of employees were intended to address recruitment, retention, or compensation parity issues. Recent salary surveys conducted by CalHR have indicated that many of these employees’ pay and total compensation lag behind people who possess similar training and qualifications and are in other bargaining units or employed by other governmental and private sector employers. For example, CalHR’s California State Employee Total Compensation Report in 2013, 2014, and 2016 determined that occupations represented by Units 2, 9, and 10 earned total compensation that was below market averages. In contrast, this report in 2013 found that correctional officers represented by Unit 6 received total compensation that was 40 percent higher than their local government counterparts.

No Evidence of Recruitment and Retention Issues. Given the time constraint we operated under to produce this analysis, the administration was not able to provide to us specific evidence of recruitment or retention issues among Unit 6 members. That being said, from the data that are available—and discussed below—we see no evidence of recruitment or retention issues to justify the large pay increase. In fact, we find that Unit 6 compensation levels likely are sufficient to allow correctional facilities to meet personnel needs at the present time.

Growing Number of New Unit 6 Members. Recruitment is the ability to attract new employees. Since 2014—after furloughs—the number of Unit 6 members with between zero years and four years of service grew from 3,857 (representing 8 percent of Unit 6 members) to 6,128 in 2017 (representing 26 percent of Unit 6 members). The growing number and share of new Unit 6 members suggests there is no recruitment issue.

Steady Share of Mid-Career Unit 6 Members. Retention is the ability to keep experienced employees. Since 2014, the number of mid-career Unit 6 members—those with between 10 years and 19 years of service—has reduced by about 5 percent from 10,308 in 2014 to 9,748 in 2017. However, the share of Unit 6 members who are mid-career has not changed between these two years. Mid-career Unit 6 members represent 41 percent of Unit 6 members.

Declining Employment Outlook for Correctional Officers. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) cites that fewer correctional officers will be needed across the United States due to changes in criminal laws (primarily related to reduced sentence time or an alternative to incarceration). Specifically, BLS estimates that between 2016 and 2026 the number of correctional officers nationally will reduce by 8 percent. This trend is apparent in California where the number of rank-and-file Unit 6 positions has reduced from 28,900 in 2003 to 26,300 in 2017. The reduced prison population following the public safety realignment likely explains much of these position reductions in California.

Pay Increases Since 2001-02 Have Exceeded Inflation. The past 20 years have seen a number of periods of time with very low inflation. Between 2001-02 and 2017-18, the average annual rate of inflation has been a little more than 2 percent. In compounded terms, inflation is expected to have grown by 45 percent between 2001‑02 and 2019-20 when measured by the U.S.-Consumer Price Index (CPI) and 54 percent when measured by California CPI. In contrast, GSIs provided to rank-and-file Unit 6 employees have grown Unit 6 base pay on a compounded basis by 59 percent before taking into account the proposed 5 percent GSI. After taking into account the proposed pay increase, Unit 6 pay will have increased 67 percent between 2001-02 and 2019-20.

Pay Increase Likely Will Be Extended to Managers and Supervisors. When rank-and-file pay increases faster than managerial pay, “salary compaction” can result. Salary compaction can be a problem when the differential between management and rank-and-file is too small to create an incentive for employees to accept the additional responsibilities of being a manager. Consequently, the administration often provides compensation to managerial employees that are similar to those received by rank-and-file employees. Extending the 5 percent GSI to Unit 6 managers and supervisors would increase state costs in 2019-20 by more than $50 million.

Pay Increase Could Increase State Pension Contribution Rate. CalPERS includes a variety of actuarial assumptions in its calculation to determine the state’s costs, including assumptions about how quickly payroll grows. Payroll is affected by (1) the number of people employed by the state and (2) the amount of money these employees earn. CalPERS assumes that payroll will grow each year by 3 percent. When payroll grows faster than 3 percent, the state’s pension unfunded liabilities grow, resulting in higher annual costs for the state to pay off a larger unfunded liability. To the extent that the 5 percent pay increase provided by this agreement contributes to payroll growing faster than 3 percent in 2019-20 (either directly or indirectly by creating a precedent or justification for agreements to provide similar pay increases to other bargaining units), the state likely will be required to contribute a larger percentage of pay to CalPERS than currently is assumed within a few years. For example, of the $424 million increase CalPERS estimates for state contribution in 2018-19, $83 million is attributed to payroll in 2016-17 growing faster than the assumed 3 percent (CalPERS found that payroll had increased by 3.7 percent).

Rising Pension Costs

Contribution Rates Expected to Grow. In recent years, CalPERS has changed a number of actuarial assumption it uses to determine employer contributions to the pension system. These assumption changes combined with investment losses have resulted in the state’s contribution rate for employee pension benefits to increase significantly over the past decade. For example, to fund pension benefits for Unit 6 members, the state contributed 25.6 percent of pay in 2007-08 but contributes 44.3 percent of pay in 2017-18. The state’s contribution rate is projected to continue growing as CalPERS phases in the effect of its decision to lower its discount rate assumption. The state is expected to contribute more than 50 percent of pay for Unit 6 pensions by 2021-22. The actual rates the state pays will be different than what is projected. For example, they will be higher than projected if CalPERS experiences investment losses or lower than projected if CalPERS experiences higher-than-assumed investment gains.

OPEB Prefunding

Contribution Rate Likely Will Need to Be Adjusted. The state’s policy to prefund retiree health benefits—first proposed by the Governor in 2015-16—is that the state and state employees agree at the bargaining table to each pay one-half of normal cost. In the case of Unit 6, both the current and the proposed agreement require the state and employees to each contribute 4 percent of pay on July 1, 2018, with the goal that the two contributions (totaling 8 percent) will equal the “actuarially determine total normal costs.” Retiree health normal cost is estimated by actuaries as a dollar amount. The administration then takes its assumption of pay in the year of the valuation to estimate the normal cost as a percentage of pay. The total normal cost for Unit 6 (including rank-and-file and associated employees who are excluded from the collective bargaining process) retiree health benefits is estimated to be $227.4 million in 2016-17 (the most recent valuation year). Using 2016-17 pay (the same year as the valuation), we estimate that 8 percent of Unit 6 pay is about $240 million—more money than is required to pay the full normal cost. Depending on future valuations, the state and Unit 6 likely will need to reevaluate the 8 percent total contribution in the future.

Legislature Could Consider Alternative to Sharing Prefunding Costs. The state has taken great strides towards addressing its retiree health liabilities by adopting a plan to prefund the benefits over the next few decades. However, as we have said in the past (see our response to the Governor’s initial proposal and our analysis of recent MOUs), we think that there is a less costly path than the one the state chose. The current cost sharing arrangement likely has resulted in higher salaries than otherwise would be the case because pay increases have been used to at least partially offset employee contributions to prefund retiree health benefits. With these higher salaries come higher salary-driven benefit costs and higher long-term state pension and leave balance liabilities. Paying the full normal cost for Unit 6 retiree health benefits would increase state costs by about $130 million in 2018-19. Unlike salary-related costs, these costs could be paid using Proposition 2 funds—freeing up General Fund resources for other programs.