LAO Contact

October 31, 2017

Review of the California Competes Tax Credit

Executive Summary

California Competes awards income tax credits to attract or retain businesses considering a significant new investment in California. In this report, we reviewed California Competes’ experience to date in meeting the Legislature’s goals for the program.

In Some Cases, Program Has Negative Economic Effects. In our review of California Competes, we find that about 35 percent of the awards—15 percent of the total dollar value—went to businesses that sell goods and services very near to them in California. These tax credits provide “windfall benefits” as they result in no change in the overall level of economic activity in the state. Moreover, these awards inadvertently harm other, equally deserving California businesses—including most of the tens of thousands of California small businesses—because the tax credits awarded to their competitors puts them at a significant competitive disadvantage.

In Many Cases, Awards Could Grow Economy but Effects Uncertain. Most of the tax credits—about 65 percent of awards representing about 85 percent of total dollar value—were awarded to businesses that sell goods and services within and outside of California. These credits may have contributed to the state’s economic growth. It is difficult, however, to assess the program’s effectiveness in attracting new investment and jobs because we cannot know what actions the businesses awarded tax credits would have otherwise taken. For example, some may have already planned to expand here. In addition, these credits have the same problem of disadvantaging all the competing companies which do not receive the credit.

Broad‑Based Policies Preferable. The executive branch has made a good faith effort to implement California Competes, but the problems described above are largely unavoidable. We recommend that the Legislature end California Competes. In general, broad‑based tax relief—for all businesses—is preferable to targeted tax incentives.

If Program Continues, Options to Make California Competes More Effective. In light of intra‑state competitions to attract new business investment, we understand that the Legislature may wish to keep California Competes as an economic development tool. If the program continues, we suggest that the Legislature (1) narrow eligibility to businesses that serve markets outside of California, (2) refocus the program on attracting jobs and investments that would otherwise locate outside California, and (3) modify the small business provisions.

Introduction

The California Competes tax credit program provides tax benefits to select businesses in exchange for meeting contractual hiring and investment targets. California Competes was created in 2013 as a part of a larger deal that replaced the state’s Enterprise Zone programs with three new economic development programs. (See the appendix for more information about the state’s former Enterprise Zone programs.) Under current law, the state may only make new California Competes tax credit awards through 2017‑18. Unless additional authority is granted in future legislation, program activities would thereafter be limited to audits and other oversight duties related to already awarded tax credits. In this report, we explain how California Competes works and review its effectiveness in attracting new investments and jobs.

Background

The Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development (GO‑Biz) is responsible for awarding California Competes tax credits to businesses. Businesses may claim the tax credit only if they meet certain investment and hiring targets set forth in written agreements negotiated with GO‑Biz. The Franchise Tax Board (FTB) is responsible for independently verifying whether the businesses complied with the terms of those agreements.

California Competes Basics

GO‑Biz Administers the California Competes Program. GO‑Biz leads the state’s economic development activities. Among its functions, GO‑Biz administers the California Competes tax credit program. In administering this tax credit program, GO‑Biz has several responsibilities that include: increasing awareness about the credit among the business community, accepting tax credit applications, evaluating applications, negotiating tax credit agreements, and monitoring agreement compliance for at least five years after the agreements are signed.

Amount of Tax Credits Available Has Increased Annually. Up to $780 million in California Competes awards are available in total between 2013‑14 and 2017‑18—$30 million in year one, $150 million in year two, and $200 million per year in each of the following three years. The Department of Finance (DOF) annually adjusts the amount available to reallocate (1) credits not awarded in a prior year and (2) “recaptured” credits (discussed below). In 2016‑17, for example, DOF allocated $243.4 million to California Competes because $39.9 million in tax credits were not awarded during the prior year and an additional $3.5 million had been recaptured. DOF may also reduce the amount of available California Competes credits under certain circumstances, which have not occurred.

GO‑Biz Conducts Outreach Activities Statewide. GO‑Biz regularly holds workshops around the state to increase awareness of California Competes and the state’s other economic development activities. Business owners and other executives, accountants, and site selection consultants attend these sessions to learn about how to apply for the tax credit. State law does not require GO‑Biz to conduct outreach. However, the Legislature provides funding for these activities in the annual budget bill. GO‑Biz has held workshops in more than 100 different California cities over the past three years. To reach a broader audience, GO‑Biz also periodically hosts workshops online and has marketed the program during some out‑of‑state trade missions.

Tax Credit Application and Evaluation Process

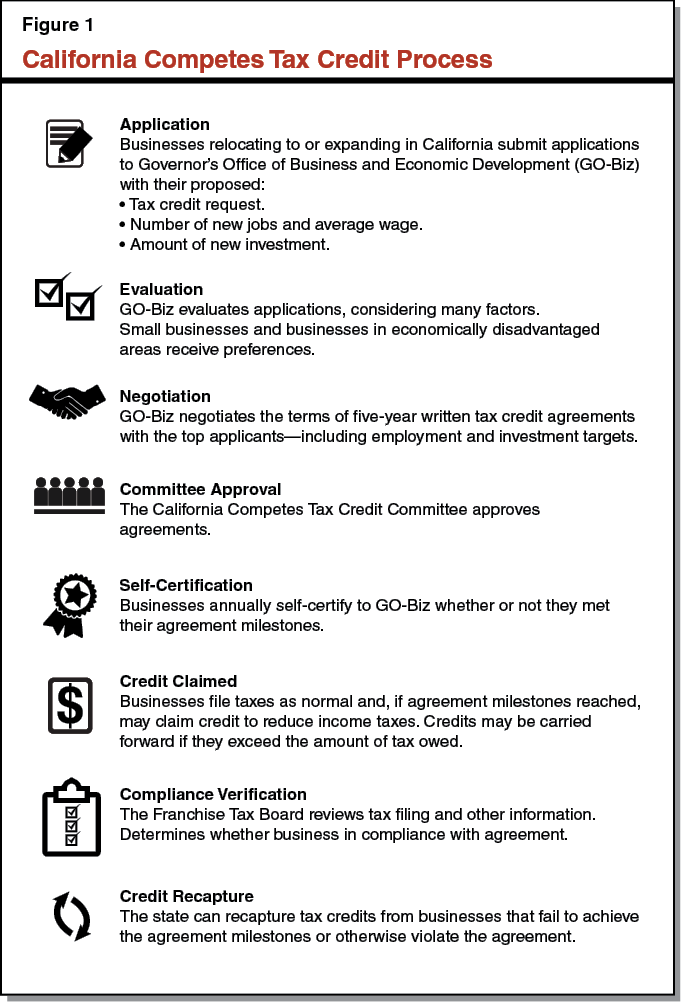

California Competes tax credits are awarded to businesses through a formal process. Figure 1 summarizes this process and we describe each step over the following pages.

Three Application Periods in 2017‑18. The first step is to submit an application. Businesses can learn about the application process from the GO‑Biz website, e‑mail notifications, the workshops discussed above, and other media. GO‑Biz accepts applications during specified periods—three such application periods have been scheduled for the 2017‑18 fiscal year:

- July 24, 2017 to August 21, 2017.

- January 2, 2018 to January 22, 2018.

- March 5, 2018 to March 26, 2018.

Businesses must submit their applications online and there is no application fee. The applicants request a tax credit amount and provide some information about their intended hiring and investment plans. GO‑Biz has received 3,045 applications between the start of the program and June 2017. About 300 businesses, on average, apply for tax credits during each application period.

Evaluation Phase 1: Applications Ranked. GO‑Biz reviews and evaluates the applications in two phases over a 90‑day period. In the first phase, GO‑Biz scores each application using the information provided by each business about their hiring and investment plans. The purpose of this first phase is to weed out the businesses planning modest expansions relative to the amount of tax credit they are requesting. In this process, a business that requests a smaller tax credit—holding constant the proposed amount of hiring and investment—receives a higher score. Applicants with the highest scores move on to the second evaluation phase. The number of applications per period has remained stable while the amount of available tax credits has increased significantly. Over the most recent two years, more than 90 percent of the applications have moved on to the second evaluation phase, compared to fewer than 70 percent during the first two years of California Competes.

Evaluation Phase 2: Additional Factors Considered. State law gives GO‑Biz broad authority to decide which businesses will receive tax credit awards. While the law requires GO‑Biz to consider the numerous factors detailed in Figure 2, GO‑Biz decides how much weight to give each factor in evaluating the applications. GO‑Biz scores each application and then negotiates tax credit agreements with the highest scoring businesses on a case‑by‑case basis.

Figure 2

California Competes Tax Credit Evaluation Factors

|

The Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development (GO‑Biz) considers the following factors when evaluating tax credit applications: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Some Businesses Receive Preferences. Current law provides several preferences for businesses that invest and hire in economically disadvantaged areas, and for small businesses. Businesses that would expand in a high‑unemployment or high‑poverty city or county automatically move on to the second phase of the evaluation process. (These areas have poverty or unemployment rates that are at least 150 percent of the statewide rates.) In addition, one‑quarter of the California Competes tax credits are set aside for small businesses. Current law defines small businesses as having less than $2 million in annual revenues. Throughout the process, GO‑Biz evaluates these small business applications separately from the rest.

Tax Credit Agreements

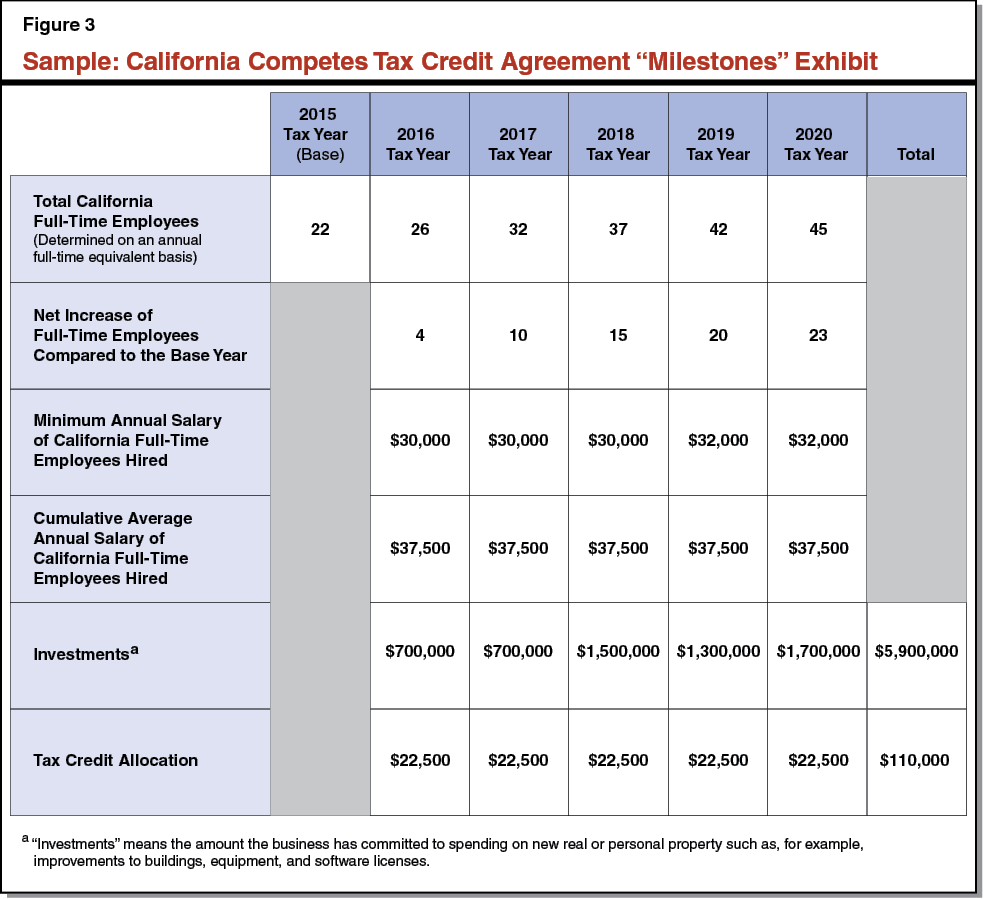

Tax Credit Agreements Individually Negotiated. GO‑Biz negotiates five‑year written tax credit agreements with the highest scoring applicant businesses. For each tax credit agreement, GO‑Biz negotiates the amount of tax credit available to the business in each of the five years and the investment and hiring commitments that the business must meet to claim their credit. These terms are summarized in a milestones exhibit that is appended to each agreement. (See Figure 3 for an example of one such exhibit.) State law also requires the agreements include a minimum job retention period. This is a period—three years in most of the agreements—subsequent to the initial five years of the agreement, during which the business may not reduce employment below the final total employment milestone. (Agreements also include various contractual details—such as reporting requirements and the conditions under which the state may recapture a tax credit. These are standard across most of the agreements.) All of the agreements are publicly available on the GO‑Biz website.

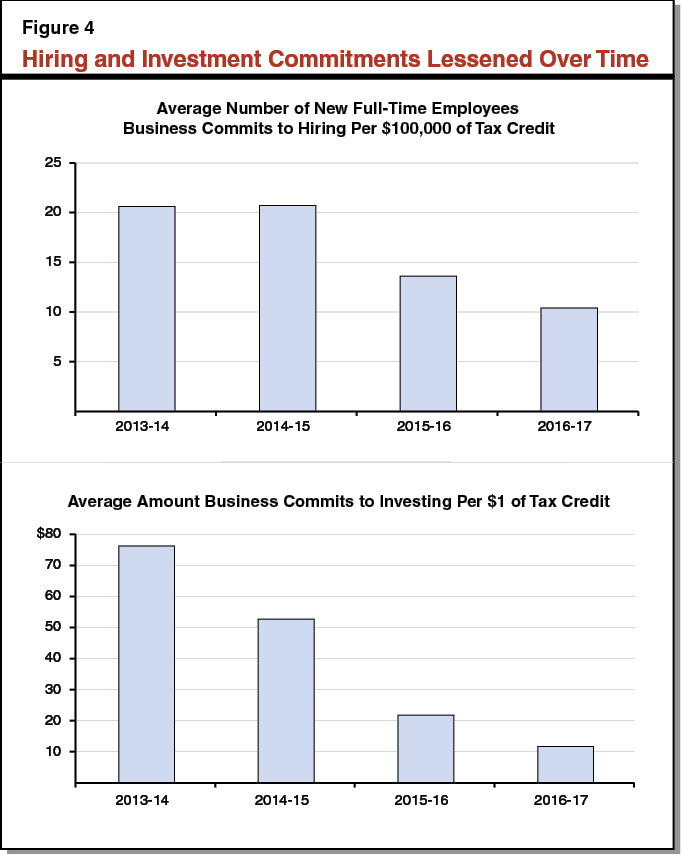

Hiring and Investment Commitments Have Lessened. The average contractual hiring and investment targets in these California Competes tax credit agreements have lessened over time. Figure 4 shows for each fiscal year the average number of new full‑time employees businesses committed to hiring for every $100,000 of tax credits and the average amount the businesses committed to invest for every dollar of tax credit. We believe that the agreement terms have lessened because the number of applicants during each cycle has remained stable—at between 250 and 350 applicants—while the amount of available tax credits increased. As we noted above, only $30 million was available in the first year of the program. DOF allocated $151 million to California Competes for 2014‑15, $201 million for 2015‑16, and $243 million for 2016‑17. Since the credits are awarded on a competitive basis, it is not unreasonable that the hiring and investment targets could decline when there are fewer applicants competing for each tax credit dollar.

Agreements Approved by Oversight Committee. The California Competes Tax Credit Committee was established to approve the tax credit agreements negotiated by GO‑Biz. The committee is comprised of the Director of GO‑Biz, the State Treasurer, the Director of Finance, or their designated representatives, an appointee of the Senate Committee on Rules and an appointee of the Speaker of the Assembly. The committee meets to publicly approve or reject the California Competes tax credit agreements negotiated by GO‑Biz staff. As of July 2017, the committee has met ten times and approved 775 agreements—about one‑quarter of the 3,045 applications.

Types of Businesses Receiving Tax Credits

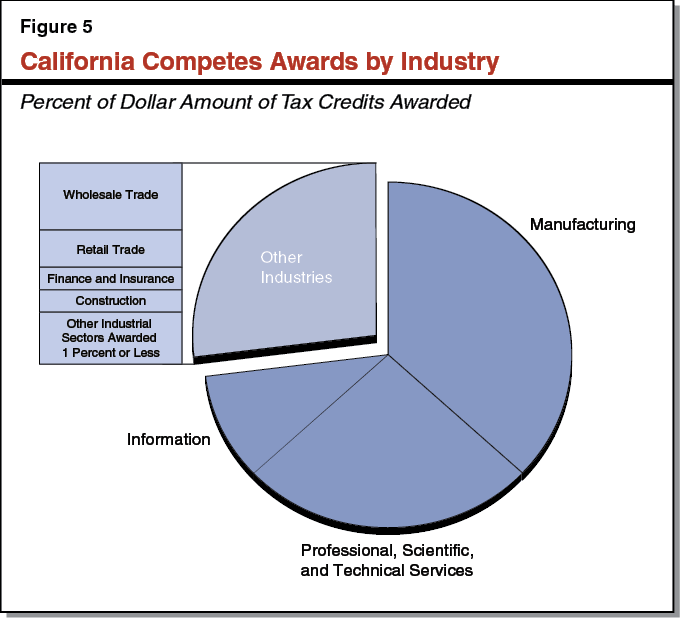

A wide variety of businesses have been awarded California Competes tax credits. Figure 5 summarizes California Competes awards by industrial sector. The manufacturing sector has received more tax credit awards—261, or more than one‑third of the tax credits by value—than any other industrial sector. The professional, scientific, and technical services sector received about 25 percent of the tax credits by value, and the information sector received about 10 percent. Other key industrial sectors with businesses receiving California Competes tax credits include wholesale trade (9 percent), retail trade (5 percent), finance (3 percent), and construction (3 percent). Within these sectors are businesses that make or distribute products to customers all over the world, as well as businesses that only sell to customers within California. The nearby box provides some examples of the types of businesses that have received California Competes tax credits within six of these industrial sectors.

Examples of Businesses Classified in Certain Industrial Sectors

The North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) is a method for grouping business establishments into standardized categories of economic production. This has several purposes, including facilitating the collection of economic data and to better understand how the structure of the economy is changing over time. The NAICS is comprised of 20 industrial sectors, such as manufacturing and information. While it may be obvious which kinds of businesses are categorized into some of these, the composition of other sectors may be less intuitive. Below, we provide several examples of businesses that have received California Competes tax credit awards in six of the most represented NAICS sectors.

|

Manufacturing |

Wholesale Trade |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services |

Retail Trade |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Information |

Finance and Insurance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

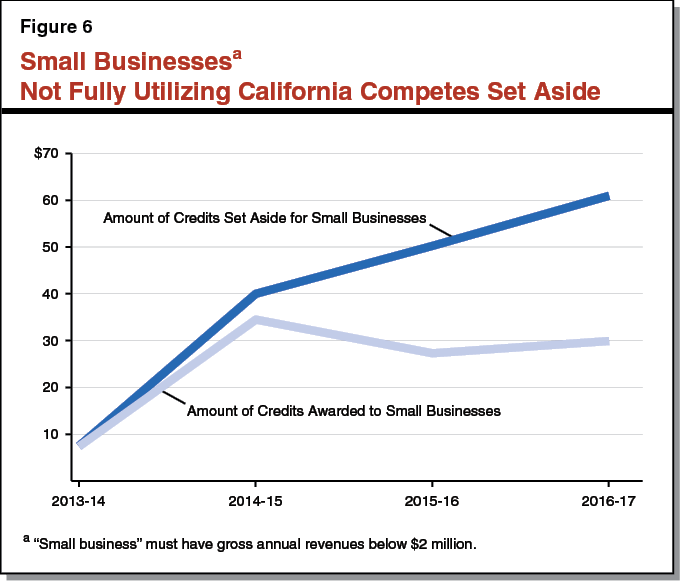

Small Businesses Not Fully Utilizing 25 Percent Set Aside. California Competes reserves one quarter of the tax credits for businesses with gross annual revenues below $2 million. As of June 2017, GO‑Biz has awarded 293 tax credit agreements—amounting to $99 million in total—to small businesses. This amount is about 19 percent of the total $528 million awarded and less than 17 percent of the $590 million that was available. While GO‑Biz sets aside 25 percent of the available tax credits for small businesses, as required, too few qualified businesses have applied to California Competes to utilize all of those credits. Figure 6 shows the amount of tax credits available to small businesses and the amount actually awarded each year. In 2016‑17, GO‑Biz awarded $30 million in tax credits to small businesses—or 49 percent of the amount reserved for them. GO‑Biz has sought to increase the number of small business applicants by increasing their outreach efforts and translating reference material into languages other than English.

Use of Tax Credits

Businesses Annually Self‑Certify Compliance. After the California Competes Tax Credit Committee approves their agreements, businesses awarded credits proceed with their expansion projects and regular order of business. At the end of their fiscal year, each of the businesses must report to GO‑Biz whether they achieved their agreement milestones. If a business met or exceeded the terms of their agreement, they may claim the tax credit when they file their income taxes. (How businesses and their owners are taxed depends on the form of the business entity. State law treats corporations and partnerships differently, for example.) If a business’ tax liability when they achieved their agreement milestones is less than the credit amount, state law allows the business to carry the remaining amount of tax credits forward for up to five subsequent taxable years.

GO‑Biz Monitors Agreement Status. If a business fails to achieve its contractual hiring and investment targets for one year, it may not claim the tax credit in that taxable year. However, such a business can “catch up” if it meets its agreement milestones in a following year. The amount of tax credits a business may claim is tied to the specific agreement milestones. For example, if a business misses its second year agreement milestones, but continues with the project during the third year, it may claim both the second and third year tax credits in the third year. In other cases, the business may not be able to achieve and maintain its milestones because, for example, of a bankruptcy or a strategic change in its business plan. In such cases so far, GO‑Biz and these businesses have voluntarily agreed to end the agreements early, allowing the state to recapture and reallocate those tax credits to other businesses. There have been 21 such cases as of June 2017.

FTB Reviews Records to Validate Compliance. State law requires FTB to “review the books and records” of businesses claiming a California Competes tax credit to ensure compliance with the terms and conditions of the written agreements. FTB is not required to audit small business recipients, although they may do so at their discretion. After a business (or individual business owner) files a tax return claiming a California Competes tax credit, FTB reviews the tax credit agreement and requests supporting information, such as documentation of equipment purchases and payroll records, from the business. FTB evaluates that information as well as information from other available sources, such as the Employment Development Department, and determines whether the business has in fact met its agreement milestones.

Tax Credit Use Somewhat Below Expectations. As of June 2017, we only have statistics on the amount of California Competes tax credits claimed for tax years 2014 and 2015. (We do not receive tax statistics until several years following the close of the taxable year. We will receive preliminary data on the use of tax credits for the 2016 tax year in November 2017.) Taxpayers claimed $3 million worth of California Competes credits in tax year 2014 and $12.6 million in tax year 2015. Based on the terms of the tax credit agreements, we anticipated somewhat larger amounts. This shortfall suggests that (1) some businesses have not achieved their agreement milestones, and (2) other businesses have carried forward a portion of their tax credits to future tax years because of an insufficient current‑year tax liability.

Tax Credits May Be Recaptured if Business Breaches Agreement. The California Competes tax credit agreements specify the conditions under which a business may be found in material breach of its agreement. This would happen if the state found a business to have falsified information or failed to maintain one or more of its agreement milestones for the specified period. This has not yet happened. However, as mentioned above, 21 businesses have voluntarily agreed to terminate their agreements. If FTB and GO‑Biz determine a business is in material breach of the terms of its agreement, they notify the business and give it time to cure the breach. If the business fails to respond to GO‑Biz or cannot cure the breach within an agreed upon time period, the California Competes Tax Credit Committee recaptures the tax credit, and FTB attempts to collect the amount of income tax the state is owed.

Assessment of California Competes

GO‑Biz Implementation

Our assessment is that GO‑Biz has implemented the California Competes tax credit program in good faith. They quickly developed a process—and adopted the necessary regulations to implement it—to award the tax credits in accordance with the program’s statutory requirements. Additionally, GO‑Biz has attempted to fairly balance the stated intent of the Legislature to maximize the effective use of taxpayer dollars with statutory requirement to consider various specific factors. As discussed below, we have found various areas where the Legislature may wish to reconsider its directions to GO‑Biz on how to implement this program.

California Competes Intended to Affect Business Behavior

States Compete for New Business Investment. During the process of selecting the site for a significant new investment, a business typically considers a variety of factors—including the proximity to their customers and suppliers and the availability and cost of skilled labor, land, energy, water, and other infrastructure. A business may also consider quality of life factors, the regulatory environment, and state and local taxes. State and local governments compete openly against one another to attract such new investments—not only based on those traditional factors particular to a location, but sometimes also by offering significant tax benefits and other financial incentives.

California Competes Intended as Economic Development Tool. In this environment, the Legislature created California Competes to provide a tool to offer state tax benefits to attract or retain individual businesses that are considering making a significant new investment in California—employers that might not otherwise invest or remain here without such a financial incentive. In other words, California Competes is intended to affect the behavior of some businesses to engage in economic activities in California they otherwise would not have taken.

Is California Competes Effective? In this section of the report, we assess the effectiveness of California Competes toward this goal: Has California Competes had a significant effect on changing business behavior in attracting new investment and jobs? We consider this question in the context of two distinct types of businesses, those doing business in the tradable sector of the economy and those in the non‑tradable sector.

Tax Credits to Non‑Tradable Businesses

Non‑Tradable Goods Produced Where Sold. Businesses producing non‑tradable goods and services are an essential component of the economy. Non‑tradable goods and services must be produced close to where they are consumed. Such goods and services have some characteristic preventing them from being easily, legally, or cost‑effectively transported between where they are produced to another state or another country. For example, heavy, commonplace, and inexpensive goods—such as gravel—are generally not tradable. While professionals in some service industries travel so that they can do business far away from where they live, this is impractical for many others—such as a plumber or a dry cleaning business. In addition, many business and household service professionals such as hair stylists, insurance agents, and architects—to provide only three examples—must be licensed by the state where they do business. Most businesses in industries such as education, health care, and construction are generally non‑tradable. (We realize that modern, inexpensive telecommunications have allowed for new business models that may blur these distinctions.) Typically, such businesses only expand when such an action would be justified by an increase in demand for their product locally or when they believe they can take market share from their local competitors.

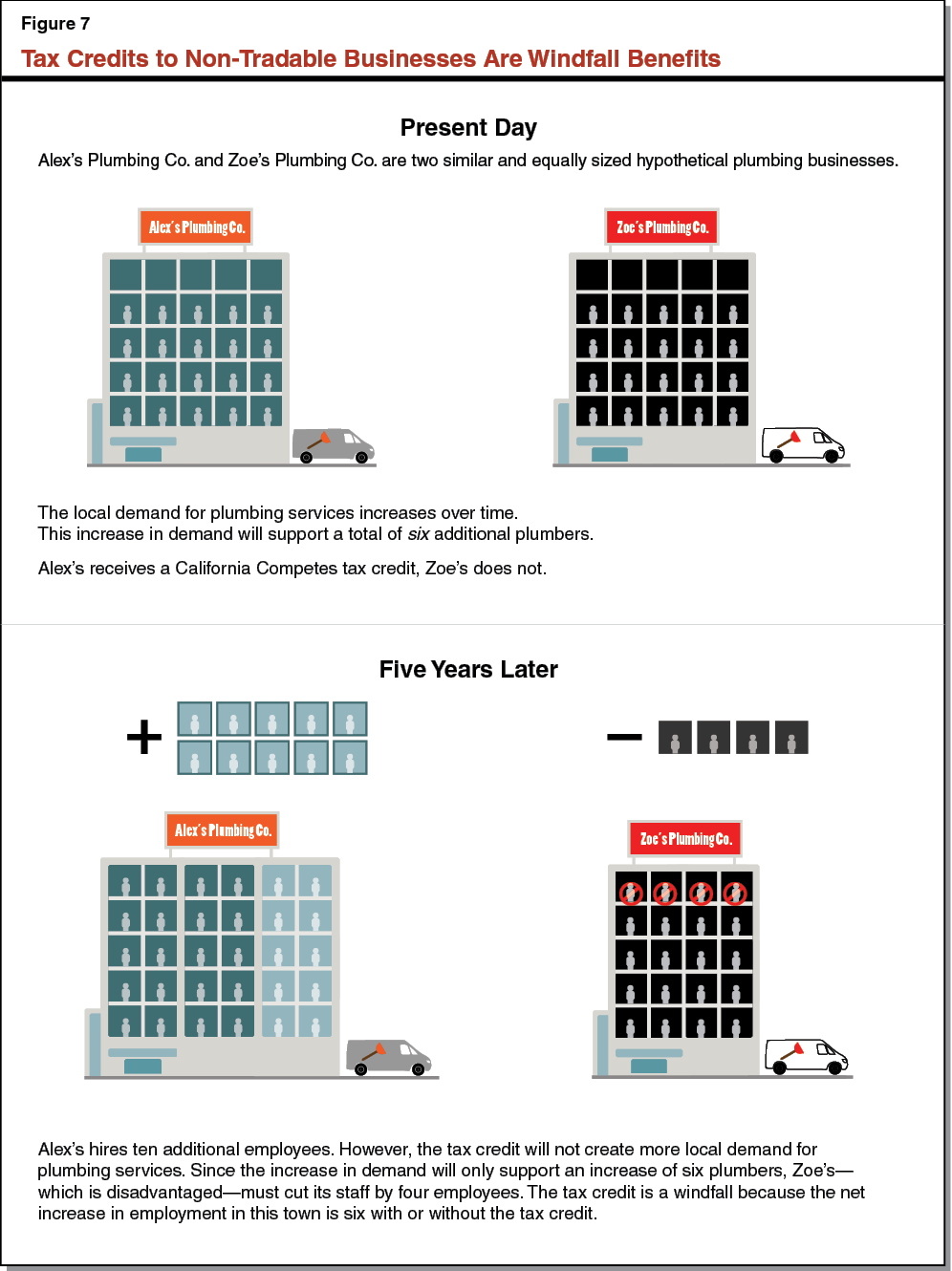

Tax Credits to Non‑Tradable Businesses Are Windfall Benefits. The California Competes tax credit is a windfall benefit for most businesses operating in the non‑tradable sector of the economy. That is, the state provides a benefit to businesses without achieving the state’s desired goal of increasing economic activity in the state. We illustrate this with an example.

Consider what might happen when one non‑tradable business—a plumbing service—receives a California Competes tax credit while its competitors do not. In the example, which we illustrate in Figure 7, Alex’s Plumbing Co. has a similar and equally sized competitor, Zoe’s Plumbing Co., and together they employ 40 people in total. The demand for plumbing services increases over time and, in this example, the two plumbing businesses will also expand by a combined total of six new employees to meet that increase in demand. If neither business receives special treatment, both Alex’s and Zoe’s will, being similar, expand at about the same pace. However, should Alex’s receive a tax credit, it would have a competitive advantage over Zoe’s—perhaps Alex’s would be able to pay its employees somewhat higher wages and charge a little bit less for its services. Alex’s receives a credit if it hires ten new employees. However, in this example, the total demand for plumbing services in the town can only support a total increase of six new plumbing employees. Zoe’s must therefore lay off four employees. In this situation, the business that received the tax credit adjusted its behavior in response to the incentive, but there was no overall increase in economic activity. Thus, the tax credit provides windfall benefits. Moreover, there are serious equity implications raised by this example. The tax credit benefited one business to the detriment of another equally deserving business.

Tax Credits to Non‑Tradable Businesses Harm Economy. As illustrated above, California Competes tax credits awarded to non‑tradable businesses have negative economic impacts. First, nearly all economic growth that might be directly attributed to the tax credit was either already going to occur or came at the expense of other California businesses. That is, the credits did not achieve the goal set out for the program of increasing the overall level of economic activity in the state (jobs and/or investments). At the same time, the tax credits have “opportunity costs”—that is, they consume state resources that would have otherwise benefited the state’s residents. For instance, the funds dedicated to the credits could have otherwise been used on other state spending priorities or on tax reductions to state residents or businesses. (We discuss opportunity costs more below.) Finally, the credits create an uneven playing field, benefitting a handful of businesses while disadvantaging other businesses.

Many Non‑Tradable Businesses Awarded Credits. We estimate that about 35 percent of the California Competes tax credit agreements were made with non‑tradable businesses. (We have attempted to distinguish between the primary industry of the business and the specific project when possible.) However, most of these tax credits awards were relatively small. As a result, we estimate that only about 15 percent of the dollar value of the tax credits were awarded to such businesses.

Tax Credits to Tradable Businesses Have Uncertain Economic Effects

Tradable Businesses Spur Economic Growth. Many goods and services are tradable. Most manufactured goods, for example, can easily be shipped to another state or another country. Inexpensive and quick telecommunications and transportation also allow many services to also be tradable. A management consultant, for example, can live and work in California and have clients located anywhere in the world. (For many professions, this tradability can vary significantly depending on the area of specialization within their field. For example, some accountants specialize in tax preparation for local clients, while others work for clients elsewhere.) Tradability is important in the context of California Competes because the expansion of such businesses need not come at the expense of other California businesses—economic growth is not a zero sum game.

Most Credits Given to Tradable Businesses. About 85 percent of the tax credit dollars have been awarded to businesses that produce goods and service that are, or could be, tradable. In these cases, it is possible that the credit changes business behavior that results in expanded economic activity in California. For example, consider a hypothetical manufacturing business, Dan’s Manufacturing Co., which is headquartered in California, but makes and exports products to customers all over the world. Dan’s currently employs 20 people at its California headquarters and 40 people at its current factory. The business is planning to expand. If it does not receive a California Competes tax credit, Dan’s will build a second factory employing 40 new employees in another state. If it receives a tax credit, it will agree to build the factory in California. In this case, the credit results in economic activity that otherwise would not take place in the state. Similarly, a credit provided to an out‑of‑state firm considering expansion could make the difference in that firm’s decision to locate in California.

Credits to Tradable Businesses May Still Have Negative Impacts. Providing credits to tradable businesses can still result in the same negative effects associated with credits awarded to non‑tradable business. The simplest example is a business that had already planned to expand in California. Such a business has little to lose in applying for a California Competes tax credit. Moreover, there is no way to know with any certainty the actual plans of any business applying to the program. Accordingly, many credits to tradable businesses still produce windfalls and are, therefore, ineffective at attracting new investment and jobs. The state has also disadvantaged all other competing businesses that did not receive a credit.

Actual Effects of Credits to Tradable Businesses Unknown. In order for the credit program to be successful, it must change a business’s decision‑making in such a way that increases jobs and/or capital investment in California. GO‑Biz can attempt to focus on certain factors that maximize this impact. For example, it could look at businesses or sectors that already had a history of migrating outside the state or look at businesses that were being induced to move with tax breaks offered by other states. Ultimately, however, there is no way of knowing what effect the California Competes tax credits have because we cannot know what firms receiving the credits would actually have done absent the credit. Given this, it will always be difficult—if not impossible—to assess the effectiveness of California Competes.

Other Issues

Price and Income Effects. The demand for all goods and services, regardless of whether they are tradable or not, is affected by their price—demand increases as price decreases. Prices of tradable goods are affected by global supply and demand but the prices of non‑tradable goods can vary significantly among places, depending on local supply and demand factors. In addition, higher incomes in a region can increase the demand for many goods and services there. The California Competes tax credit may affect the local prices, supply, and demand of some goods and services in areas where non‑tradable businesses receive a tax credit. This may also increase wages—the price of labor—for some employees, leading to higher household incomes (and higher incomes subsequently increase the demand for some goods and services). All of these changes have complicated economic effects—positive for some people, negative for others—beyond those discussed above.

Opportunity Costs. Tax credits provide special state tax benefits for some taxpayers. As such, tax credits have obvious fiscal impacts in that they reduce state revenue. In doing so, tax credits reduce the amount of money that is available for other purposes. California Competes will reduce state revenues by up to $780 million over about 15 years, resources that state policymakers could otherwise use to fund other state programs, reduce debt, or allow for alternative tax reductions. Whatever this foregone revenue would have funded would have benefitted the state’s residents in some way. This foregone benefit is the opportunity cost of California Competes. The Legislature has to consider the benefits of California Competes with the benefits of alternative uses of the tax resources funding this program.

Recommendation and Options

Allow California Competes to End

Broad‑Based Benefits Preferable to Targeted Tax Incentives. California Competes—as a tax credit program—has similar issues inherent in other such programs, such as the motion picture production tax credit and the research and development tax credit. These include windfall benefits, economic inefficiency, the unequal treatment of similar taxpayers, and opportunity costs. For these reasons, we generally are highly skeptical of tax programs that target specific businesses or industries. If the Legislature is inclined to provide some amount of tax relief—or some other economic development incentive—to businesses, we would recommend ending California Competes and instead adopting a broad‑based policy change generally applicable to all businesses. Such policies could include (1) reducing the corporate tax rate, (2) reducing the minimum tax (under current law, nearly all business entities annually pay a minimum tax of $800 regardless of their net income), or (3) other policy changes to improve the state’s business climate generally.

Options if This Program Is Continued

If, on the other hand, the Legislature decides to continue California Competes, we suggest several changes that could partially address the problems we have noted. Possible changes include:

- More narrowly targeting the program to tradable businesses.

- Refocusing the program on its core mission as a tool for interstate economic development competitions.

- Modifying the small business provisions.

Narrow Eligibility to Tradable Companies. An important change would be to prohibit GO‑Biz from awarding California Competes tax credits to businesses that primarily sell to customers in California. GO‑Biz has made hundreds of awards to local service providers such as accountants, auto mechanics, residential contractors, and medical doctors—all businesses with predominantly local clients. Some of these businesses clearly state in their advertising that they serve a specific geographic area—“now serving Fresno, Clovis, and Madera,” in one example. To effectuate this change, GO‑Biz could, for example, be required to review the tax returns of applying businesses and their affiliates during the application process—which would indicate how much of their income comes from California sources. Exceptions to such a rule should be very limited—for example, to California businesses with very strong prospects for using their tax savings to fund an expansion of sales to out‑of‑state customers.

Refocus Credit to “Level Playing Field” With Other States, Countries. The very name of this program—California Competes—evokes its goal: to help California compete against other states and countries to convince businesses to locate, stay, and expand here. Unfortunately, GO‑Biz has negotiated about one‑third of its tax credit agreements with California businesses that compete primarily against other California businesses. These tax credits are windfall benefits. As we explained above, many of the tax credits also inadvertently harm other, equally deserving California businesses—many of them small businesses—that do not receive tax credits. These agreements also take a significant amount of time to negotiate and monitor—time that GO‑Biz could otherwise use to pursue better agreements. To this end, we recommend that the Legislature consider clarifying and emphasizing its intent regarding the program in state law. We believe the original intent of the program was to win competitions against other states and countries for major or growing businesses seeking to locate, relocate, or expand—for example, to attract businesses with tax incentive offers from other states and countries. If California Competes continues, the Legislature could clarify in law that this is its main focus.

Modify Small Business Provisions. California Competes provides no benefits to most of California’s small businesses. Only several hundred such businesses, out of many tens of thousands, have received a tax credit award. In fact, many small businesses are harmed when a competing business is awarded a significant benefit that they do not also receive. If the Legislature would like to help small businesses, a policy that benefits all such businesses would be significantly more beneficial than California Competes. Consistent with these goals and the need to refocus California Competes on its original purposes, we recommend eliminating the requirement under current law that 25 percent of the tax credits be reserved for small businesses. If California Competes continues, under the options we outline above, some small businesses that are in the tradable sector of the economy could still qualify for tax credits. These typically would be small businesses exporting goods and services outside California. Recognizing that some eligible small businesses may lack the resources and expertise to competitively apply for the California Competes tax credit, the Legislature, in adopting this option, could require GO‑Biz to devote some amount of staff resources to assist eligible small businesses in applying for the amended program.

Conclusion

The competitiveness of the California economy—compared to that of other states and countries—is a longstanding concern of state policymakers. Hearing complaints about California’s regulatory environment and the relatively high rates of some state and local taxes, lawmakers have attempted over the years to devise programs that cut taxes for select businesses—aiming to help bolster the state’s ability to attract and keep high‑value employers, while at the same time minimizing public revenue losses. The Legislature’s efforts to devise programs like California Competes are understandable in this context. However, we have repeatedly found that tax benefits delivered selectively to a small portion of California businesses are highly problematic. Picking winners and losers inevitably leads to problems. In the case of California Competes, we are struck by how awarding benefits to a select group of businesses harms their competitors in California. We also think the resources consumed by the program are not as focused as they should be on winning economic development competitions with other states to attract major employers that sell to customers around the country and the world.

We recommend that the Legislature consider providing broad‑based tax benefits to all California businesses instead of continuing California Competes. Alternatively, if the Legislature wishes to continue the program, we suggest changes that would focus it on helping California compete to attract and retain high‑value employers while avoiding harm to existing California businesses.

Appendix

California’s Enterprise Zone (EZ) Programs: 1984 Through 2013

EZs Encouraged Business Expansion in Certain Targeted Areas. For nearly three decades, the state’s primary economic development programs provided extensive tax benefits to employers that relocated to or expanded in areas targeted by the Legislature based largely on the socioeconomic characteristics of the geographic area and the prevailing level of economic distress there. EZs were first adopted in 1984 and subsequently expanded several times to also include Manufacturing Enhancement Areas, Targeted Tax Areas, and Local Agency Military Base Recovery Areas. (It was common to collectively refer to all of these programs as “Enterprise Zones.”) The intent of the EZ programs was to use the state’s tax code to increase economic opportunities for the people living and working in economically distressed areas of the state. The tax benefits offered to businesses located in EZs included hiring credits, sales and use tax credits, accelerated depreciation, net interest deductions for lenders, and a longer carryforward of net operating losses. There were about 40 active EZs in 2012.

State’s Former EZ Programs Ineffective. The EZ programs were popular and their use grew rapidly. In 2010, the hiring and sales tax credits resulted in $698 million of reduced corporation and personal income tax revenues for the state. This amount grew at an average annual rate of 18 percent between 2000 and 2010. Statewide, however, most rigorous research found that EZs did not create a net increase in jobs or increase the rate of job creation. While some EZs may have resulted in more job growth in a particular place, most of those jobs were likely shifted from other parts of the state.

Economic Development Programs Overhauled in 2013. The Legislature comprehensively changed state economic development programs in 2013. Chapter 69 and Chapter 70 of 2013 (AB 93, Committee on Budget, and SB 90, Galgiani) eliminated EZs and replaced them with three new economic development programs:

- A partial sales tax exemption for purchases of certain manufacturing equipment.

- A tax credit for hiring by qualified businesses in certain, specified areas.

- California Competes—a program that provides hiring and investment tax credits to select businesses on a case‑by‑case basis.