In November 2016, voters approved Proposition 57, which made various changes affecting the state's adult and youth correctional systems. In this report, we first describe state law and practice prior to the implementation of Proposition 57 and provide a description of the provisions of the measure. We then describe and assess the administration's proposals to implement Proposition 57 and provide various recommendations for legislative consideration.

LAO Contact

LAO Report

April 6, 2017The 2017-18 Budget

Implementation of Proposition 57

Introduction

In November 2016, voters approved Proposition 57, which made various changes affecting the state’s adult and youth correctional systems. In this report, we first describe state law and practice prior to the implementation of Proposition 57 and provide a description of the provisions of the measure. We then describe and assess the administration’s proposals to implement Proposition 57 and provide various recommendations for legislative consideration.

Background

Adult Sentencing and Parole Consideration. Individuals are placed in prison under an indeterminate sentence or a determinate sentence. Under indeterminate sentencing, individuals are sentenced for a term that includes a minimum but no specific maximum, such as 25-years-to-life. These individuals typically appear in-person before the state Board of Parole Hearings (BPH) for a parole consideration hearing in order to be granted release from prison.

Under determinant sentencing, individuals receive fixed prison terms with a specified release date. Most people in prison have received a determinate sentence. Certain determinately sentenced inmates can be considered for parole and released before they have served their entire sentence. For example, certain individuals convicted of nonviolent offenses who were previously convicted of a serious or violent offense are eligible for parole consideration part way through their prison sentence. These particular individuals are commonly referred to as “nonviolent second strikers” because they were sentenced under the state’s three strikes law. (Please see the nearby box for more detailed information about the state’s three strikes law.) Specifically, pursuant to a federal court order related to prison overcrowding, nonviolent second strikers are currently considered for parole after they have served half of their sentence. (As we discuss in a nearby box, the federal court imposed several measures to keep the state’s prison population below a certain limit.)

Three Strikes Sentencing

In 1994, the California Legislature and voters (with the passage of Proposition 184) changed the state’s criminal sentencing law to impose longer prison sentences for certain repeat offenders (commonly referred to as the “three strikes” law). Proposition 36, approved by voters in 2012, narrowed the type of repeat offenders subject to some of these longer sentences. Currently, state law requires that a person who is convicted of a felony and who previously has been convicted of one or more violent or serious felonies be sentenced to state prison as follows:

- Second Strike Offense. If the person had one previous serious or violent felony conviction, the sentence for any new felony conviction (not just a serious or violent felony) is twice the term otherwise required under law for the new conviction. Offenders sentenced by the courts under this provision are referred to as “second strikers.”

- Third Strike Offense. If the person has two or more previous serious or violent felony convictions, the sentence for any new serious or violent felony conviction is a life term with the earliest possible parole after 25 years. In addition, an offender with two or more previous serious or violent offenses who commits any new felony (not just a serious or violent felony) can be similarly sentenced to a life term if he or she has committed certain new or prior offenses, including some drug-, sex-, and gun-related felonies. Offenders convicted under this provision are referred to as “third strikers.”

Federal Court Ordered California to Limit Prison Population

In November 2006, plaintiffs in two ongoing class action lawsuits—now called Plata v. Brown (involving inmate medical care) and Coleman v. Brown (involving inmate mental health care)—filed motions for the courts to convene a three-judge panel pursuant to the U.S. Prison Litigation Reform Act. On August 4, 2009, the three-judge panel declared that overcrowding in the state’s prison system was the primary reason that the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) was unable to provide inmates with constitutionally adequate health care. Specifically, the court ruled that in order for CDCR to provide such care, overcrowding would have to be reduced to no more than 137.5 percent of the design capacity of the prison system. (Design capacity generally refers to the number of beds that CDCR would operate if it housed only one inmate per cell.) The court ruling applies to the number of inmates in prisons operated by CDCR, and does not preclude the state from holding additional offenders in other public or private facilities.

To comply with the prison population cap, the state took a number of actions, including (1) housing inmates in contracted facilities, (2) constructing additional prison capacity, and (3) reducing the inmate population through several policy changes. For example, in 2011, the state shifted the responsibility for housing and supervising certain lower-level felons to counties. In 2014, to ensure that the state complied with the cap, the three-judge panel ordered CDCR to develop and implement several additional population reduction measures including a parole consideration process for nonviolent second strikers and expanded credit earning for minimum-custody inmates and certain second strikers.

Sentencing Credits. The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) awards credits to inmates that reduce the time they must serve in prison. Credits are provided for good behavior or for participating in work, training, or education programs. Currently, inmates are limited in the types of credits that they can earn, as well as the amount that that their sentences can be reduced through credits. Existing state statutes allow inmates to reduce their prison terms primarily through two types of credits:

Good Conduct Credits. Eligible inmates earn good conduct credits when they avoid violating prison rules and/or participate in certain workgroups, such as fire camps. Statute prohibits some inmates, such as third strikers, from earning good conduct credits. Statute also includes various limits on the rate at which inmates can earn such credits. For example, most violent offenders are eligible to reduce their prison term by up to 15 percent under current law. In addition, with certain exceptions (such as for nonviolent second strikers and violent offenders) inmates who work as fire fighters (or have completed training to do so) are eligible to reduce their sentence by up to two-thirds. Good conduct credits can improve prison operations by incentivizing inmates to follow prison rules and participate in workgroups.

Milestone Credits. CDCR awards milestone credits to inmates for completing certain rehabilitation, education, or work training programs. For example, inmates can earn two weeks off of their sentence for completing a three-month substance abuse program or two weeks off of their sentence for completing certain welding courses. Currently, only nonviolent, non-sex registrant, non-third strikers are eligible to earn milestone credits. These inmates can reduce their prison term by up to six weeks per year through milestone credits. To the extent that the specific programs for which inmates can earn milestone credits are effective in reducing recidivism, milestone credits can improve public safety by incentivizing inmates to participate in such programs.

In addition, certain inmates are eligible to earn credits at rates that exceed the limits specified in state law pursuant to the above federal court order to reduce prison overcrowding. For example, statute specifies that nonviolent second strikers can only reduce their terms by 20 percent through good conduct credits. However, the court order allows nonviolent, non-sex registrant second strikers to reduce their terms by up to 33 percent through such credits.

Criminal Court Proceedings for Youths. Individuals accused of committing crimes when they were under 18 are generally tried in juvenile court. Counties are generally responsible for the youths placed by juvenile courts. These youths are typically allowed to remain with their families under the supervision of county probation, with some placed elsewhere (such as in county-run camps). However, judges can place youths that commit certain major crimes (such as murder, robbery, and certain sex offenses) in a facility operated by CDCR’s Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ).

Under certain circumstances, youths can be tried in adult court. Youths convicted in adult court can receive adult sentences and typically are first held in a state juvenile facility and then transferred to state prison after they turn age 18.

Major Provisions of Proposition 57

Proposition 57, which was approved by the voters in November 2016, made various changes related to the state’s criminal justice system. Specifically, the measure (1) makes all nonviolent offenders eligible for parole consideration, (2) expands CDCR’s authority to award sentencing credits to inmates, and (3) requires that judges decide whether juveniles should be tried in adult court. The measure states that these changes are intended to protect public safety, save money by reducing spending on prisons, prevent federal courts from releasing inmates, and reduce recidivism through rehabilitation.

Makes All Nonviolent Offenders Eligible for Parole Consideration. Proposition 57 amended the State Constitution to specify that individuals convicted of a nonviolent felony offense shall be eligible for parole consideration after completing the term for their primary offense. The primary offense is defined as the longest term imposed excluding any additional terms added to an offender’s sentence, which include any sentencing enhancements (such as the additional time an inmate serves for prior felony convictions). As a result, BPH could release nonviolent offenders after they serve the term for their primary offense—allowing some offenders to be released from prison and placed on parole earlier than otherwise. The measure requires CDCR to adopt regulations to implement this change.

Expands CDCR Authority to Award Sentencing Credits. Proposition 57 amended the State Constitution to specify that CDCR shall have the authority to award credits to inmates for good behavior and rehabilitative or educational achievements. Accordingly, CDCR may increase the number of inmates eligible to earn credits and allow inmates to reduce their sentences through credits by more than what is currently allowed in statute. The measure authorized CDCR to adopt regulations to implement changes to credits.

Requires Judges to Decide Whether Youths Should Be Tried in Adult Court. Proposition 57 changed statute to require that all youths have a hearing in juvenile court before they can be transferred to adult court. As a result, prosecutors can no longer file charges directly in adult court and no youths can have their cases heard in adult court on a mandatory basis due to the circumstances of the offense. Accordingly, there will likely be fewer youths tried in adult court, and, eventually, fewer youths sent to state prison. Instead, it is likely that more youths will be placed under county jurisdiction and/or in a DJJ facility.

Administration’s Plan to Implement Proposition 57

As part of the Governor’s January budget proposal for 2017-18, the administration outlined its plan to implement Proposition 57. This plan was revised somewhat and formalized in emergency regulations submitted to the Office of Administrative Law (OAL) on March 24, 2017. The OAL must review these regulations within 20 calendar days of their submission. If approved by OAL, the emergency regulations will remain in effect for 160 days and can be extended for up to two additional 90 day periods. These emergency regulations will become finalized if CDCR adopts them through the regular rulemaking process within this time period.

Specifically, the administration proposes to:

- Implement New Nonviolent Offender Parole Consideration Process. On July 1, 2017, the administration plans to begin the parole consideration process for nonviolent offenders.

- Expand Sentencing Credits. The administration plans to increase the number of credits inmates earn for good behavior and participation in rehabilitation programs. It anticipates that changes to good conduct credits will go into effect on May 1, 2017 and that changes to credits inmates earn for participation in rehabilitation programs, such as modifications to milestone credits, will go into effect on August 1, 2017.

- Make Various Budget Adjustments to Reflect Proposition 57 Implementation. The Governor’s January budget includes various funding adjustments to reflect the administration’s initial plan for implementing the new nonviolent offender parole consideration process and changes to sentencing credits, as well as the requirement in Proposition 57 that all youths have a hearing in juvenile court before they can be transferred to adult court. The budget reflects the administration’s estimates for how its initial plan would impact the state’s inmate, parolee, and juvenile ward populations, and the number of offenders supervised by county probation departments. However, as indicated above, the administration’s implementation plan subsequently changed as reflected in recently released emergency regulations. For example, the Governor’s budget assumes an October 1, 2017 implementation date while the emergency regulations assume earlier implementation dates as described above. The administration indicates that it will propose budgetary changes to reflect its current implementation plan as part of the May Revision.

Below, we provide greater detail on each aspect of the administration’s plan, assess its merits, and provide recommendations for legislative consideration.

Implementation of Parole Consideration Process

Administration’s Plan

As authorized in Proposition 57, the administration plans to begin parole consideration of nonviolent offenders after they complete the term for their primary offense. The specific process outlined in the emergency regulations is modeled after the nonviolent second striker parole process ordered by the federal court.

Key components of the administration’s plan include:

- Exclusion of Certain Offenders With Nonviolent Convictions. As previously indicated, Proposition 57 specifies that nonviolent offenders shall be eligible for parole consideration after completing the term for their primary offense. The emergency regulations define “nonviolent offenders” in such a way as to exclude certain offenders convicted of nonviolent offenses from the parole consideration process authorized in Proposition 57. Specifically, nonviolent offenders required to register as sex offenders (whether or not their current offense is a sex offense) and nonviolent “third strikers” who are serving indeterminate sentences under California’s three strikes law would not be eligible for the new parole consideration process. The administration also plans to exclude nonviolent offenders who recently committed certain rule violations in prison.

- Inclusion of Certain Offenders With Violent Convictions. The administration’s emergency regulations make certain offenders convicted of offenses defined in statute as violent eligible for the new parole consideration process. Specifically, the emergency regulations make eligible certain offenders who have completed a prison term for a violent felony but are still serving a prison term for a nonviolent felony offense that they were convicted of at the same time.

- Inmate File Reviews Rather Than Actual Hearings. As part of the parole consideration of nonviolent offenders, BPH indicates that it does not plan to conduct in-person hearings. (Currently, BPH conducts in-person hearings primarily for inmates serving indeterminate sentences.) Instead, similar to the nonviolent second striker parole process, a BPH deputy commissioner would review certain information about an inmate collected by CDCR. The inmate would be approved for parole if the information reviewed by the deputy commissioner indicates that the inmate does not pose an unreasonable risk of violence. According to BPH, this determination would be based on the following factors: (1) circumstances surrounding the crime (such as whether a weapon was used); (2) prior criminal record; (3) institutional behavior and rehabilitation program participation; and (4) any input provided from victims, the district attorney, and the inmate.

- Review Initiated After Primary Term Served. While Proposition 57 states that nonviolent offenders shall be eligible for parole consideration after completing the term for their primary offense, it does not specify when BPH can begin the review process for an inmate. The administration, however, is interpreting Proposition 57 to prohibit deputy commissioners from beginning to review inmates’ files until after they have served the full term for their primary offense. As a result, under the administration’s plan, an inmate who is granted parole under the new process would not be released immediately following his or her primary term.

LAO Assessment

Administration’s Plan Subject to Change. As indicated above, the administration recently released emergency regulations outlining the new parole consideration process for nonviolent offenders. These emergency regulations will become finalized if CDCR adopts them through the regular rulemaking process. However, the final regulations could ultimately be different than the emergency regulations if the department chooses to modify them, such as in response to public comments received through the regulatory process.

Exclusion of Certain Nonviolent Offenders Appears to Violate Measure. We find that the administration’s plans to exclude nonviolent third strikers and sex registrants from the new parole consideration appears to violate the language of Proposition 57. This is because the proposition specifies that all inmates serving a prison term for a nonviolent offense shall be eligible for parole consideration. By automatically excluding nonviolent sex registrants and third strikers, the administration would not provide parole consideration to this subset of these offenders.

Uncertain Whether Including Certain Offenders With Violent Convictions Permitted. It is uncertain whether the administration’s plan to include certain offenders who have completed a prison term for a violent felony but are still serving a prison term for a nonviolent felony offense that they were convicted of at the same time is consistent with the intent of Proposition 57. This is because the measure could be interpreted to limit eligibility to inmates who were sent to prison for nonviolent offenses.

Initiating Process After Primary Term Completed Appears Unnecessarily Costly. Based on the administration’s plan not to initiate the parole consideration process until after nonviolent offenders have completed their primary term, inmates approved for parole would not be released immediately. Instead, inmates would have their case reviewed and decided on by a deputy commissioner after completing their primary term. While this particular process could be done relatively quickly, if approved for parole, the inmates would then go through reentry planning activities (such as receiving pre-release risk and needs assessments), which the administration reports take about 60 days to complete. As such, these inmates would not be released until around 60 days—in some cases more depending on the actual timing of the review process—after they have served the full term for their primary offense.

On the other hand, if BPH initiated the parole consideration process sometime before nonviolent offenders completed their primary term, CDCR could release inmates approved for parole shortly after their primary term and achieve the associated population reduction and savings. One way this could be done is for BPH to make a preliminary release decision 60 days before such inmates complete their primary terms. Reentry planning activities would then occur during the 60 days between the preliminary release decision and when inmates complete their primary terms. A final parole consideration decision—based on a review of inmates’ behavior in the 60 days since the preliminary release decision and any other relevant new data available—would be made upon the completion of inmates’ primary terms. We note that in some cases, this could result in reentry plans being made for some inmates who are ultimately not released under the new parole consideration process.

To the extent that such an alternative approach reduces the time nonviolent offenders serve in prison by two months, we estimate that this approach could potentially result in several millions of dollars in savings annually relative to the Governor’s proposal depending on the actual number of offenders approved for parole. While a portion of these savings could be offset by the cost of reentry planning for inmates who are ultimately not released, these additional costs are likely to be minor.

Parole Consideration Process Inherently Subjective. Throughout an inmate’s time in prison, CDCR records specific information on him or her, such as the extent to which the inmate participated in rehabilitation programs and rules violations. In preparation for the parole consideration process, BPH would supplement this information by soliciting input from victims, district attorneys, and the inmate. By the time the inmate is actually considered for parole, BPH would have a multitude of qualitative and quantitative data about the inmate. Deputy commissioners would use these various types and sources of information to make a release decision.

According to CDCR, deputy commissioners currently use their professional judgement to synthesize various sources and types of information about inmates to make a decision about whether to release an inmate for the nonviolent second striker parole process. However, this process is inherently subjective. For example, it is possible that deputy commissioners could over or under value various aspects of inmate data they review, such as criminal history or completion of rehabilitation programs. In addition, it can be difficult to ensure that different deputy commissioners make decisions in a consistent and completely transparent manner that is free from any unconscious biases.

In order to improve accuracy and reduce subjectivity of parole board decisions, several states use statistically validated, structured decision-making tools as part of their parole consideration process. These tools guide commissioners through a process of weighing several different sources of information about an inmate. For example, Pennsylvania’s Parole Decisional Instrument combines the results of several actuarial risk assessments and inmates’ institutional behavior and programming history into a numerical score, yielding a parole recommendation that commissioners can supplement with their qualitative observations. Accordingly, decisions guided by such instruments weigh factors in a consistent manner; are transparent, as they can be shown to be based on specific factors; and are less likely to be subject to unconscious bias. In addition, research suggests that such actuarial tools can improve public safety by yielding better release decisions than professional judgment alone.

LAO Recommendations

Direct Administration to Report on Final Regulations. We recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to provide a report no later than 30 days after the regulations on the new parole consideration process for nonviolent offenders are finalized. This report should (1) summarize the final regulations, (2) discuss how the final regulations differ from the emergency regulations (including justification for any differences), and (3) identify how the changes affect CDCR’s budget and populations.

Direct Administration to Justify Definition of Nonviolent Offender. We recommend that the administration report at budget and policy hearings on the following issues:

The legal and policy basis for excluding nonviolent sex registrants and third strikers from the parole consideration process.

The legal basis for including in the nonviolent offender parole consideration process certain offenders who have completed a prison term for a violent felony but are still serving a prison term for a nonviolent felony offense.

Seek Advice From Legislative Counsel on Timing of Parole Consideration. In order to ensure that the measure is implemented in the most effective and efficient manner, we recommend that the Legislature consult with Legislative Counsel to determine whether Proposition 57 allows BPH to initiate parole consideration before an inmate completes his or her primary term. If Legislative Counsel advises the Legislature that BPH can begin parole consideration as such, we recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to report, during spring budget hearings, on how it could begin to consider inmates for parole prior to completion of their primary terms.

Direct BPH to Investigate Using a Structured Decision-Making Tool. Given the potential benefits, we recommend that the Legislature direct BPH to investigate using a structured decision-making tool in the future. Specifically, we recommend that the Legislature direct BPH to report by December 1, 2018 on available structured decision-making tools and the estimated costs, opportunities, and challenges associated with adapting such tools for use in parole consideration reviews required by Proposition 57, as well as the other parole processes conducted by BPH. (This should give BPH time to focus on implementing the new parole consideration process before considering changes to it.) This report would allow the Legislature to determine whether to require BPH to use such a tool in the future.

Implementation of New Sentencing Credits

Administration’s Plan

As authorized in Proposition 57, the administration plans to increase the amount of good conduct credits inmates can earn beginning on May 1, 2017 and to increase the number of credits inmates earn through participation in rehabilitation programs beginning on August 1, 2017. Figure 1 summarizes the administration’s current plan relative to existing credits authorized in statute and by federal court order. We note that only good conduct credits subject to change are depicted in Figure 1 as the administration is not proposing to change all good conduct credits.

Figure 1

Administration’s Planned Changes to Inmate Credit Earning

|

Inmates Affected |

Current |

Planned |

|

Good Conduct Credits |

||

|

Most violent offenders |

Up to 15% |

Up to 20% |

|

Nonviolent third strikers |

— |

Up to 33.3% |

|

Inmates in fire camps, firehouses, or who have completed training for these assignments |

||

|

Up to 15% |

Up to 50% |

|

Up to 33.3% |

Up to 66.6% |

|

Milestone Credits |

||

|

Non-sex registrant, nonviolent, non-third strikers |

Up to 6 weeks per year |

Up to 12 weeks per year |

|

All other inmates except those sentenced to death and life without the possibility of parole |

— |

Up to 12 weeks per year |

|

New Educational Merit Credits |

||

|

All inmates except those sentenced to death and life without the possibility of parole |

— |

3 to 6 months per achievement |

|

New Participation Credits |

||

|

All inmates except those sentenced to death and life without the possibility of parole |

— |

Up to 4 weeks per year |

Specifically, CDCR plans to increase credit earning in the following ways:

- Increase Good Conduct Credits. Currently, violent offenders can generally reduce their prison terms by as much as 15 percent with good conduct credits. However, some violent offenders, such as third strikers, cannot reduce their prison terms through good conduct. CDCR plans to allow violent offenders—except condemned inmates and those sentenced to life without the possibility of parole—to reduce their prison term with good conduct credits by up to 20 percent. Nonviolent third strikers, who are currently ineligible for good conduct credits, would be able to reduce their terms by up to one-third. In addition, the administration plans to increase good conduct credits for certain offenders working or trained to work as firefighters. Specifically, violent offenders would receive one day of credit for every day served with good behavior and nonviolent second strikers would receive two. The administration expects these changes to go into effect on May 1, 2017.

- Expand Milestone Credits. As previously discussed, currently only nonviolent, non-sex registrant, non-third strikers are eligible to earn milestone credits to reduce their prison term by up to six weeks per year. Effective August 1, 2017, CDCR plans to expand eligibility for milestone credits to all inmates except those serving life terms without the possibility of parole and condemned inmates. In addition, the administration plans to increase the amount of credits inmates earn for completing many programs and increase the limit on the annual amount of milestone credits that an inmate can earn to 12 weeks. However, we note that in a few cases the administration is planning to reduce the amount of credits that inmates will earn for specific programs. For example, the amount of credits earned for completing Guiding Rage Into Power (GRIP)—a program seeking to help inmates reduce violent behavior—will be decreased from four to two weeks.

- Create New Educational Merit Credits. Effective August 1, 2017, CDCR plans to offer new credits for specific educational achievements. The administration plans to reduce inmates’ terms by between three and six months when they accomplish these achievements, such as earning a high school diploma, earning a bachelor’s degree, or becoming certified to provide alcohol and drug counseling to other inmates. These credits would be applied retroactively, meaning that inmates who have completed these achievements before August 1, 2017 would be awarded the credits immediately.

- Provide Participation Credits for Certain Programs. Effective August 1, 2017, CDCR plans to offer credits (referred to as “rehabilitative achievement credits”) to inmates who demonstrate sustained participation in particular programs and activities for which the department does not otherwise award credits. The department has not provided a list of these programs and activities but has indicated that they will be selected by wardens and will likely include inmate affinity and self-help groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous and Toastmasters. Inmates would be allowed to earn up to four weeks of participation credits per year.

Codify Court-Ordered Credits in Regulation. As discussed earlier, the federal court required CDCR to implement certain credits that exceed limits specified in existing statutes, such as allowing nonviolent, non-sex registrant second strikers to reduce their terms by up to 33 percent through good behavior. The administration plans to include these court-ordered changes into its planned regulations. Accordingly, inmates will continue to receive these credits once the court order is lifted.

LAO Assessment

Administration’s Plan Subject to Change. Similar to the regulations on parole consideration, the administration has only released emergency regulations for its planned changes to credit policies. The final regulations could ultimately be different than the emergency regulations if the department chooses to modify them, such as in response to public comments received through the regulatory process.

Lack of Information on Inmate Access to Programs. The population impact of CDCR’s planned milestone and participation credits will depend on inmates’ access to the programs that yield credits. However, the administration indicates that it has not done an analysis of how the availability of these programs will impact credit earning under their plan. On the one hand, the changes in these credits could reduce the inmate population by less than the administration expects if there is not enough capacity in rehabilitative and educational programs to allow inmates to earn the number of credits assumed by the administration. On the other hand, to the extent there is more than enough capacity, the planned changes to credit earning could impact the population by more than the administration expects. This creates significant uncertainty about how Proposition 57 will actually impact the state’s inmate population. Such uncertainty makes it difficult for the Legislature to evaluate the Governor’s proposed budget adjustments.

Effectiveness of CDCR’s Programs Remain Unclear. Inmates who participate in approved programs earn credits, which allow them to accelerate their release, regardless of whether the programs are effective in reducing their risks to public safety. In order to protect public safety, it is critical that the approved programs are effective at reducing recidivism. However, CDCR currently has only done a limited analysis of the effectiveness of its programs. This analysis found that the recidivism rates of offenders who received substance use disorder treatment reoffended at lower rates than those who had not. While many of the other programs offered in prisons have been shown to be effective elsewhere, analyses of California’s current implementation of these programs have not been completed.

Unclear Rationale Behind Credit Reduction for Certain Programs. As discussed above, the administration plans to reduce credits awarded for a few programs, including GRIP and two theology programs. It is unclear why the administration chose to reduce credits awarded for these programs.

LAO Recommendations

Direct Administration to Report on Final Regulations. We recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to provide a report, no later than 30 days after the regulations on credit policies are finalized, that summarizes the final regulations. This report should (1) summarize the final regulations, (2) discuss how the final regulations differ from the emergency regulations (including justification for any differences), and (3) identify how the changes affect CDCR’s budget and populations.

Direct Department to Assess Program Capacity. We recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to report at budget hearings on the number and type of programs through which inmates would receive credits, the current capacity and attendance rates for these programs, and the corresponding effect they may have on the inmate population. This information would allow the Legislature to assess whether the current availability of programs is sufficient. The Legislature could then decide whether it needs to adjust funding for programs accordingly.

Direct Administration to Evaluate Credit-Yielding Programs. We recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to contract with independent researchers (such as a university) to evaluate the effectiveness of its rehabilitation programs and that it prioritize credit-yielding programs for evaluation. We estimate that such evaluations would cost a few million dollars and could take a few years to complete. The outcomes of the evaluations would allow the Legislature in the future to prioritize funding for programs that have been shown to reduce recidivism.

Direct Administration to Explain Credit Reductions. We recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to report during budget and policy hearings on its rationale for reducing milestone credits for specific programs.

Fiscal Impacts of Proposition 57

Governor’s Proposals

The Governor’s January budget proposal for 2017-18 includes various adjustments that reflect the administration’s initial plan to implement the provisions of Proposition 57. As indicated above, the administration plans to make further adjustments as part of the May Revision to reflect the March 2017 emergency regulations. Figure 2 summarizes the fiscal impacts of Proposition 57, which we discuss in more detail below.

Figure 2

Fiscal Impacts Related to Proposition 57a

(In Millions)

|

2017-18 |

|

|

Staff and resources to implement new parole consideration process and credit policies |

$6.5 |

|

Inmate population reduction |

-47.8 |

|

Parolee population increase |

7.1 |

|

Juvenile population increase |

4.8 |

|

Grants to counties for increased post release community supervision population |

6.4 |

|

Total |

-$23.0 |

|

aCalculated based on administration’s population estimates made before release of emergency regulations. |

|

Staff and Resources to Implement Parole Consideration Process and Credit Policies. The Governor’s January budget proposes a $6.5 million General Fund augmentation and 20.9 positions in 2017-18 to implement the new parole consideration process and credit policies. Specifically, these resources include:

- Case Records Staff ($4.1 Million). The administration proposes funding for CDCR to support five additional case records positions and overtime for current staff to (1) process inmate release and parole eligibility date changes as a result of expanded credit earning and (2) screen inmates for eligibility for the nonviolent offender parole process. We note these funds would decline in future years as this workload decreases.

- BPH Staff ($1.2 Million). The administration proposes funding to support 2.3 additional positions at BPH to coordinate communications with victims and district attorneys for the new parole consideration process. The proposed funds would also allow BPH to hire an additional parole commissioner and 4.4 additional deputy commissioners to consider inmates for release. The administration also proposes budget trailer legislation that would allow the Governor to expand the number of BPH commissioners from 14 to 15.

- Pre-Release Planning and Parole Case Records Staff ($1.2 Million). The administration proposes these funds to support 8.2 additional positions at CDCR’s Division of Adult Parole Operations to do pre-release planning and manage case records for the anticipated increase in the parolee population caused by Proposition 57.

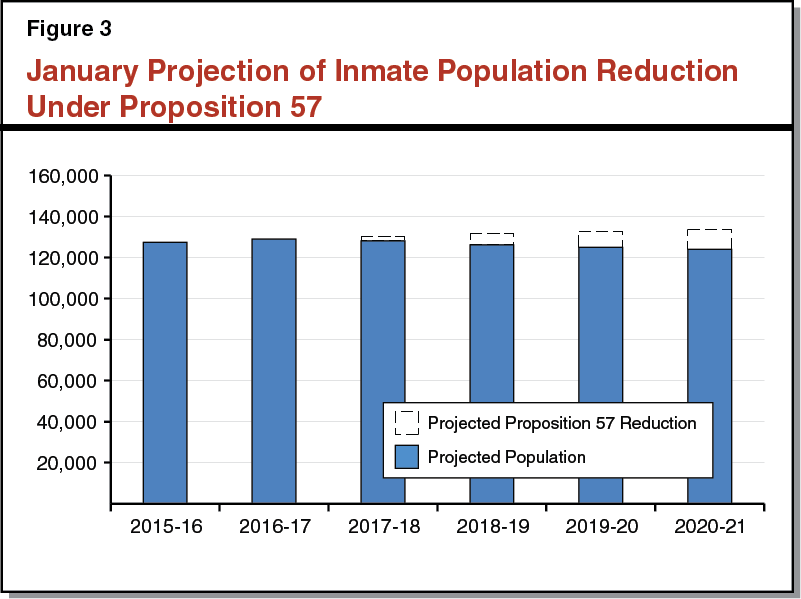

Inmate Population Reduction. By expanding inmates’ opportunities to be released before they have served their full sentence, the administration’s new parole consideration process and credit policies will reduce the state’s inmate population. As shown in Figure 3, the Governor’s January budget projects that the administration’s initial plan for implementing Proposition 57 would reduce the inmate population by about 2,000 in 2017-18. We estimate that this decrease would allow the department to avoid about $48 million in costs it would have incurred in the absence of the measure. The population impact of the measure is expected to grow to an average daily population reduction of about 9,500 by 2020-21. The administration expects that this decline in the inmate population will allow it to remove inmates from one of two out-of-state contract facilities in 2017-18 and from all out-of-state contract facilities by 2020-21.

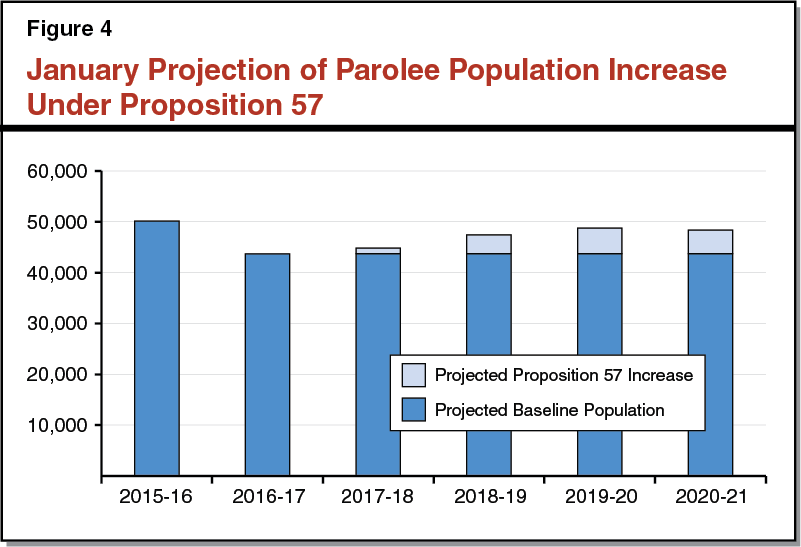

Parolee Population Increase. Because the administration’s plan to implement Proposition 57 will increase the rate at which inmates will be released from prison, it will temporarily increase the parolee population. Specifically, as shown in Figure 4, the Governor’s January budget projects that its initial plan for implementing Proposition 57 will temporarily increase the parolee population by about 1,000 in 2017-18. Accordingly, the Governor’s budget reflects an increase in the parole budget of about $7.1 million in 2017-18. The parolee population impact is expected to grow to about 5,000 by 2019-20 and to generally decline thereafter.

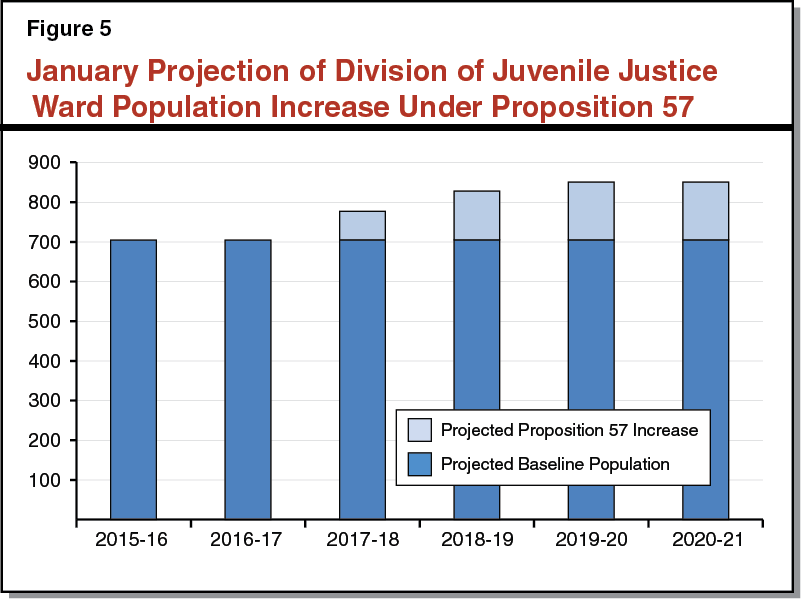

Juvenile Population Increase. The administration expects that the new juvenile transfer hearing requirement will increase the number of youths committed to DJJ. Specifically, as shown in Figure 5, the Governor’s January budget projects that Proposition 57 will increase the DJJ ward population by 72 in 2017-18. Accordingly, the administration is proposing a $4.8 million General Fund augmentation in 2017-18 to accommodate this increase. Most of these funds would be used to activate two additional living units, one at N.A. Chaderjian Youth Correctional Facility in Stockton and the other at Ventura Youth Correctional Facility in Camarillo. The population impact is expected continue to increase to about 145 wards by 2020-21.

Grants to Counties for Increased Post Release Community Supervision (PRCS) Population. Offenders whose current offense is nonserious and nonviolent are placed on PRCS and supervised by county probation departments rather than state parole agents when they are released from prison. Because Proposition 57 will increase the rate at which inmates will be released from prison, it will temporarily increase the PRCS population. Accordingly, the Governor’s January budget proposes to provide counties with $6.4 million in 2017-18 on a one-time basis to offset some of the costs they will incur from the temporary increase in the PRCS population. The administration reports that counties will be provided with $10,250 to supervise each PRCS offender for a period of 18 months.

LAO Assessment

Budgetary Impacts Subject to Change. As mentioned above, the administration’s implementation plan changed somewhat between the release of the Governor’s January budget proposal and the release of the emergency regulations in March 2017. These changes to the implementation plan will likely alter somewhat the administration’s projected population impacts and budget requests, though at the time of this analysis the administration had not provided these updates.

In addition, as discussed previously, the regulations for the nonviolent offender parole consideration process and new credit earning policies are not yet finalized. Accordingly, the administration’s implementation plans and timeline are subject to further change, which raises additional uncertainty about their budgetary effects.

Population Impacts of Proposition 57 Are Difficult to Predict. Even if the administration’s regulations do not change, its projections of the Proposition 57 impacts would still be subject to uncertainty because of the inherent difficulty of projecting the effects of the measure. For example, the effects of the parole consideration process will depend on decisions made by deputy parole commissioners. Similarly, the effects of the proposed credit expansion will depend on how inmates respond to increased good conduct credit earning rates and credits for participating in programs and activities as well as the capacity of these programs. Finally, the effect on DJJ will depend on decisions made by juvenile court judges.

LAO Recommendation

Withhold Action Pending the May Revision. Uncertainty in the population impacts of Proposition 57 makes it difficult to assess the Governor’s population-related budget requests. In addition, uncertainty in the timing of and workload required to implement and operate the new parole process and credit policies make it difficult to assess the Governor’s requested funding for implementation. Given these uncertainties, we recommend that the Legislature withhold action on the administration’s January budget adjustments pending the receipt of revised adjustments from the administration.