LAO Report

January 5, 2017Evaluation of CSU's Doctor of Nursing Practice Pilot Program

- Introduction

- Background on Nursing Education Programs

- The DNP at CSU

- Findings

- LAO Assessment and Recommendation

Executive Summary

Background

State Assigns Distinct Missions to Higher Education Segments. California’s Master Plan for Higher Education, dating back to 1960, and existing state law assign specific missions to each of the public higher education segments. The state generally gives the University of California (UC) responsibility for independent doctoral degrees but permits the segment to award joint doctoral degrees with the California State University (CSU).

To Help State Address Nursing Shortage, Legislation Permits CSU to Offer Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) on Pilot Basis. In the late 1990s, California began experiencing a statewide shortage of registered nurses (RNs). Experts at the time forecasted that the shortage would continue to worsen absent an increase in the supply of RNs. To boost enrollment capacity in its nursing programs, CSU cited a need to increase the number of nursing faculty holding a doctoral degree, which is required for faculty seeking tenured and tenure–track university positions. To this end, CSU expressed interest in establishing its own DNP program, independent from UC. The state enacted Chapter 416 of 2010 (AB 867, Nava) to address the nursing workforce challenge. As a temporary exception to the Master Plan, Chapter 416 allowed CSU to offer an independent DNP on a pilot basis at up to three campuses.

CSU’s Interest in DNP Program Also Linked With Anticipated Increase in Nursing Educational Requirements. In addition to addressing the nursing shortage, CSU sought DNP authorization to help the state meet an anticipated new educational requirement for higher–level nurse clinicians. Specifically, in 2004, a national organization of nursing schools endorsed a nonbinding statement that identified the DNP as the most appropriate entry–to–practice degree for advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) and called for nursing master’s programs that train APRNs to transition to the DNP by 2015.

Legislative Analyst’s Office to Evaluate Pilot. Chapter 324 of 2015 (SB 103, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) directed us to assess CSU’s DNP programs and make a recommendation on whether the pilot should be extended beyond its 2018 sunset date. This report fulfills that statutory requirement.

Major Findings

CSU Formed Two DNP Consortia Consisting of a Total of Five Campuses. In response to Chapter 416, CSU grouped five campuses into two consortia—the Northern California Consortium (consisting of the Fresno and San Jose campuses) and the Southern California Consortium (consisting of the Fullerton, Los Angeles, and Long Beach campuses). Both consortia operate programs five semesters long (spanning 21 months), with instruction—much of it online—occurring in fall, spring, and summer terms.

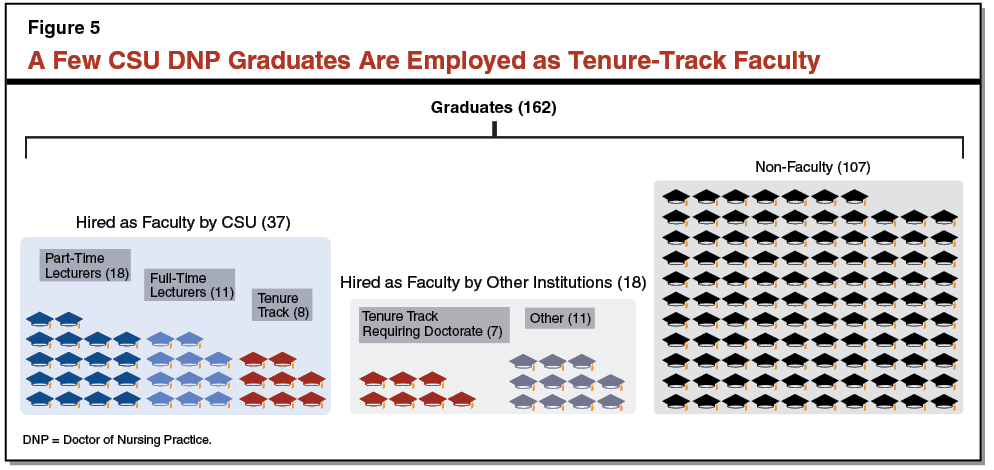

About One–Third of CSU’s DNP Graduates Are Serving as Faculty but Few Graduates Are in Tenure/Tenure–Track Positions. The first DNP students began their studies in fall 2012 and graduated in spring 2014. Through the first three cohorts, CSU reports that 162 of a total 174 students (93 percent) have graduated with a DNP. Of the 162 graduates, 55 (34 percent) serve as faculty at CSU or other postsecondary institutions. Most of these graduates are in part–time or other faculty positions that do not require a doctorate.

LAO Assessment and Recommendation

State No Longer Facing Nursing Shortage. The Legislature authorized Chapter 416 at a time when it believed California faced a long–term mismatch between the supply of and demand for RNs. Yet, soon after the legislation was enacted, the state’s shortage eased considerably. Today, the Board of Registered Nursing and other experts report that overall the state’s RN labor market is in good balance and, assuming current graduation production continues, supply is sufficient to ensure an adequately sized RN workforce for decades to come.

CSU Continues to Report Trouble With Attracting Doctorally Prepared Nursing Faculty . . . While CSU no longer needs to hire large numbers of new faculty to address an RN shortage, CSU still reports difficulty recruiting tenure–track nursing faculty to fill positions that become vacant due to retirement and turnover. For example, a Chancellor’s Office survey of three of the largest CSU nursing schools found that of eight tenure–track positions advertised in 2015–16, six were cancelled for lack of a sufficient pool of candidates.

. . . But Only a Few DNP Graduates Helping CSU With Regular Hiring Needs. Despite CSU having open positions go unfilled, the pilot has produced only a few tenure–track faculty. To date, only 8 of 162 graduates (5 percent) have taken a tenure–track position at CSU.

Increasing Compensation Levels for Nursing Faculty More Direct Way for CSU to Address Regular Recruitment Challenges. The primary reason CSU cites for its ongoing difficulty attracting tenure–track nursing faculty is the relatively low salaries that such faculty receive compared with nurse clinicians and administrators. A more direct way for CSU to address its recruiting challenges, thus, would be to offer more competitive salaries. CSU already has authority to pay differential salaries. For example, the average salary of entry–level, tenure–track nursing faculty currently is about $10,000 more than their history faculty peers and about $25,000 less than their business faculty peers.

For the Most Part, Expectations About Higher Entry–to–Practice Requirements for APRNs Have Not Materialized. CSU also justified an independent DNP program based on an expectation at the time that the degree would become a requirement for APRNs by 2015. Yet, with one future exception (for nurse anesthetists), accreditors and licensing agencies continue to require APRNs to hold just a master’s degree.

Other Options Available to Individuals Seeking a DNP. At the time the Legislature authorized Chapter 416, the number of DNP programs available to potential students was relatively small. Today, nearly 300 DNP programs—many of them online—are offered throughout the country. In addition, three UC campuses currently are seeking to offer DNP degrees by 2018.

Recommend Legislature Allow Pilot to Sunset. Given that a nursing shortage no longer exists, CSU has more direct ways to attract tenure–track nursing faculty, the DNP has not become the required degree for APRNs, and an increasing number of other DNP programs are now available to students, we recommend the Legislature allow the CSU DNP pilot to sunset.

Introduction

State law generally gives the University of California (UC) sole authority to award doctoral degrees. As one of only a handful of exceptions to this rule, Chapter 416 of 2010 (AB 867, Nava) authorizes the California State University (CSU) to independently award a doctoral degree in nursing, the Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP), on a pilot basis. Chapter 324 of 2015 (SB 103, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) requires the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) to evaluate the pilot program and report to the Legislature by January 1, 2017. This report fulfills that statutory requirement. The report has four main sections. In the first section, we provide background on nursing education programs. In the second section, we describe CSU’s two pilot DNP programs. In the third section, we present our findings on program implementation. In the final section, we assess the program and make a recommendation regarding its extension.

Back to the TopBackground on Nursing Education Programs

Below, we provide information on pre– and post–licensure nursing programs as well as registered nurses (RNs) and advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs).

Nursing Education Includes Pre–Licensure and Post–Licensure Programs. California’s more than 300,000 licensed nurses provide a variety of health care services in various settings, including hospitals, medical offices and clinics, extended care facilities, and labs. All RNs in the state must have a license issued by the California Board of Registered Nursing. To obtain a license, students must graduate from an approved nursing program, pass a national licensing examination, and complete certain other steps (such as undergoing a criminal background check). Nursing education consists of pre–licensure programs for individuals seeking to become an RN and post–licensure programs for RNs seeking to prepare for higher–level practice as APRNs, administrative roles, or careers in teaching and research. As discussed below, California’s public higher education system plays a major role in providing both types of programs.

Pre–Licensure Programs

Each of the Three Types of Pre–Licensure Programs Involve Student Learning in Various Settings. In California, three main types of pre–licensure education programs are available to persons seeking to become an RN. The first two options are for students to enroll in either (1) an associate degree in nursing program at a two–year college or (2) a four–year bachelor’s degree in nursing program at a university. In addition, some master’s degree nursing programs accept individuals who hold a bachelor’s degree in a non–nursing field. Generally, students in such a master’s program complete educational requirements for an RN license in about 18 months, then continue for another 18 months to obtain a master’s degree in nursing. (These master’s degree programs do not prepare individuals to work as APRNs.) All three types of pre–licensure programs combine classroom instruction, “hands on” training in a simulation lab, and clinical placement in a hospital or other health facility. Graduates of these programs typically find nursing positions providing direct care to patients.

California Community Colleges and CSU Are Key Providers of State’s Pre–Licensure Programs. Currently, 132 public and private colleges in California offer a total of 138 pre–licensure programs. Figure 1 shows that the California Community Colleges and CSU are two of the major educators of RNs, with community colleges offering 78 of the state’s 90 associate degree programs and CSU offering 17 of the state’s 36 bachelor degree programs and 2 of the state’s 12 pre–licensure master’s programs. A total of 11,119 students graduated from a pre–licensure program in 2014–15—half with associate degrees and the remaining half with bachelor’s or master’s degrees.

Figure 1

Nursing Pre–Licensure Programs in California

|

Number of Programs |

Number of Graduates |

|

|

Associate’s Degree in Nursing |

||

|

California Community Colleges |

78 |

4,844 |

|

County of Los Angeles program |

1 |

87 |

|

Private institutions |

11 |

611 |

|

Subtotals |

(90) |

(5,542) |

|

Bachelor’s Degree in Nursing |

||

|

CSU |

17 |

1,628 |

|

UC |

2 |

97 |

|

Private institutions |

17 |

3,135 |

|

Subtotals |

(36) |

(4,860) |

|

Master’s Degree in Nursinga |

||

|

CSU |

2 |

109 |

|

UC |

2 |

144 |

|

Private institutions |

8 |

464 |

|

Subtotals |

(12) |

(717) |

|

Totals |

138 |

11,119 |

|

aReflects programs enrolling students who do not yet have a registered nursing license. Source: Board of Registered Nursing. |

||

Post–Licensure Programs

RNs have opportunities to pursue post–licensure degrees in nursing. These programs include a master’s degree, Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in nursing, and DNP.

Master’s Degree in Nursing

Post–licensure master’s degree programs can prepare RNs for a variety of advanced roles and specialty areas. These master’s degree programs typically take a student two years of full–time enrollment to complete.

Many Post–Licensure Master’s Degree Programs Focus on Preparing APRNs. Most commonly, nursing students enroll in a master’s degree program to become an APRN. These programs have four tracks: (1) nurse practitioner, (2) nurse anesthetist, (3) nurse midwife, and (4) clinical nurse specialist. (We describe each of these tracks in the next paragraph.) The APRN master’s degree curriculum typically includes foundational coursework such as nursing theory and research methods, as well as core clinical content such as physical health assessment, illness and disease management, and pharmacology. In addition to attending classes, nurses studying to become APRNs must spend considerable time in instructional (simulation) labs and clinical settings. Students completing a post–licensure master’s degree program in nursing must be certified by the Board of Registered Nursing to work as an APRN in California, and they may take national examinations in their respective nursing roles to receive national certification. (Some employers require their nurses to have both state and national certifications.) As discussed in the nearby box, APRNs work under physician supervision.

Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs)

California Requires APRNs to Work Under Supervising Physicians. Pursuant to California law, an APRN must work under the supervision of a physician. (Other states permit APRNs to practice without supervision.) Generally, the level of supervision and specific services provided to patients are determined by an agreement laid out between an APRN and the supervising physician. While statute sets forth no requirements regarding the geographic proximity between a physician and an APRN, the physician is expected to be able to effectively supervise the APRN in fulfilling the service agreement. At a minimum, statute requires supervising physicians to be available by telephone at the time of a patient examination. Statute specifies that physicians may supervise up to four APRNs if the nurses are allowed to write drug prescriptions. Physicians have no limitations on the number of APRNs they may supervise if the nurses do not write drug prescriptions.

Students Training to Become APRNs Enroll in a “Track.” Specifically, individuals may enroll in one of the following four educational tracks:

- Nurse Practitioner. Nurse practitioners, the most common type of APRN, perform health assessments, diagnose patients’ conditions, and treat illnesses and injuries.

- Nurse Anesthetist. Nurse anesthetists administer anesthesia to patients undergoing surgery in hospitals, dental offices, and other clinical settings.

- Nurse Midwife. Nurse midwives have training in prenatal care, assisting mothers with childbirth, and postpartum care.

- Clinical Nurse Specialist. Clinical nurse specialists provide consultative services to other health care staff and often devise protocols for improving patient and hospital safety. For example, a clinical nurse specialist may consult with nursing staff to advise on the most effective wound care techniques for an elderly patient recovering from surgery.

Within the nurse practitioner and clinical nurse specialist tracks, APRNs further specialize by population group (such as pediatrics or women’s health). Universities typically offer a breadth of such specialty options.

Some Students in Master’s Programs Pursue a Non–APRN Track. Some master’s degree students choose a non–APRN track, such as nursing administration or nursing education. Students on the administration track often aspire to leadership positions within health organizations, whereas the education track prepares nurses to teach in practice settings (such as teaching diabetes management to patients) or at educational institutions (such as at community colleges or nontenure–track positions at universities).

CSU Is a Notable Provider of Master’s Degree Programs. As Figure 2 shows, 35 public and private institutions in California offer at least one post–licensure master’s degree program in nursing. In 2014–15, these institutions granted 1,983 master’s degrees in nursing. CSU is a notable provider of such programs—accounting for 43 percent of institutions and 31 percent of graduates.

Figure 2

Nursing Post–Licensure Graduate Programs in California

|

Number of Programs |

Number of Graduates |

|

|

Master’s Degree in Nursing |

||

|

CSU |

15 |

606 |

|

UC |

4 |

304 |

|

Private institutions |

16 |

1,073 |

|

Subtotals |

(35) |

(1,983) |

|

Doctor of Philosophy, Nursing |

||

|

UC |

4 |

30 |

|

Private institutions |

3 |

41 |

|

Subtotals |

(7) |

(71) |

|

Doctor of Nursing Pratice |

||

|

CSUa |

2 |

53 |

|

Private institutions |

8 |

140 |

|

Subtotals |

(10) |

(193) |

|

Totals |

52 |

2,247 |

|

aPilot programs. Source: Board of Registered Nursing (for master’s degree data) and Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (for doctoral program data). |

||

Ph.D. in Nursing

Ph.D. in Nursing Is a Research–Oriented Degree. Like the Ph.D. in various other disciplines, the primary purpose of the nursing Ph.D. is to prepare students for careers in research and academia. Nursing students in Ph.D. programs generally are interested in advancing theory and discovering new knowledge about nursing science (on topics such as providing care to persons with chronic diseases, older adults, and vulnerable populations). Ph.D. programs focus heavily on coursework in theory development, research methodology, and data analysis, and students are required to complete an original research project (dissertation). After earning a master’s degree, nursing students typically take about four years to earn a Ph.D.

UC Is the State’s Public Provider of Ph.D. Programs. As Figure 2 shows, the state currently has seven universities that offer a Ph.D. in nursing, including four UC campuses. According to the federal Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), 71 students received a Ph.D. in nursing in California in 2014–15, 42 percent of which graduated from UC.

Doctor of Nursing Practice

DNP Is Designed for Practitioners. The DNP is a relatively new doctoral degree. The first DNP program began in 2001 (at the University of Kentucky). In contrast to the Ph.D., the DNP is designed for nurse professionals who either provide direct care to patients or serve in certain leadership positions (such as hospital administration). Whereas the Ph.D. is concerned primarily with scientific research, the DNP focuses on understanding research and applying it to practice. DNP programs typically include topics such as reading and interpreting research studies, using health care information systems to make more–informed clinical decisions, and policy advocacy. Rather than completing a dissertation, DNP students typically write a shorter “capstone” paper that evaluates a health care program or identifies clinical strategies for improving quality control and patient care.

Two Routes to the DNP—Post–Master’s and Post–Bachelor’s. According to the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), 289 DNP programs operated in the United States in 2015, enrolling nearly 22,000 students. According to a 2014 study by the RAND Corporation, most DNP programs are “post–master’s” programs, meaning that RNs must earn a master’s degree before applying to and enrolling in a DNP program. These DNP programs are relatively short in length—typically entailing 18 months of full–time attendance. Some universities have “post–bachelor’s” DNP programs, which educate bachelor’s–prepared RNs to become APRNs at the doctoral level. These post–bachelor’s programs combine clinical instruction found in traditional master’s programs (such as patient assessment and treatment) with additional coursework in health care technology, leadership, and other DNP subjects. Bachelor’s–to–DNP programs typically take students about three years of full–time study to complete.

DNP Not Currently a Requirement for APRNs. In 2004, members of AACN endorsed a nonbinding statement that (1) identified the DNP as the most appropriate degree for APRNs to enter clinical practice and (2) called for nursing master’s programs that train APRNs to transition to the DNP by 2015. While the position statement helped to spur the development of DNP programs nationwide (at the time of the 2004 vote, there were just three DNP programs in the country serving a total of 107 students), the master’s degree—not the DNP—currently remains the entry–to–practice requirement for APRNs. A future exception will be for nurse anesthetists. The Council on Accreditation of Nurse Anesthesia Educational Programs is requiring all nurse anesthetist programs to be at the doctoral level by 2022 and all new candidates for certification to have a doctoral degree by 2025. (In 2015, the National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists endorsed the DNP as the entry–to–practice degree for clinical nurse specialists by 2030. As of this writing, however, none of the accreditors of clinical nurse specialist programs has acted on that position statement.)

CSU Offers Two of the State’s Ten DNP Programs. Currently, ten universities in California offer the DNP. According to IPEDS, these programs graduated a total of 193 students in 2014–15. The following sections discuss CSU’s two DNP pilot programs.

Back to the TopThe DNP at CSU

Below, we describe CSU’s rationale for wanting to operate independent DNP programs and identify the statutory requirements the state established for these programs.

CSU’s Objective

The CSU advocated an independent DNP program to address a special set of circumstances, as explained below.

CSU Has Two Main Types of Faculty. As in other disciplines, CSU nursing programs employ tenured/tenure–track faculty and lecturers. Tenured/tenure–track faculty generally are employed on a full–time basis and are expected to engage in teaching, research, and university service (such as serving on campus committees). By contrast, lecturers typically are employed on a part–time basis and have only teaching responsibilities. Another difference between the two types of faculty are the educational requirements. Historically, tenured/tenure–track nursing faculty have been required to have a Ph.D. (or other terminal degree, such as a Doctor of Education [Ed.D.]), whereas lecturers need only have a master’s degree. Like tenured/tenure–track faculty, nursing lecturers can teach and supervise students in various settings (including in the classroom for theory–based courses), though they are disproportionately assigned to supervise and instruct students in simulation labs and at clinical sites. As of fall 2015, CSU campuses employed a total of 217 tenured/tenure–track nursing faculty and 675 part– and full–time lecturers. As postsecondary accreditors do not set specific standards on the staffing mix, CSU nursing programs vary on the ratio of tenured/tenure–track faculty and lecturers they employ. For example, in fall 2015, 24 percent of CSU, Fullerton’s nursing faculty were tenured/tenure–track, as compared with 14 percent at San Diego State University.

In Response to Nursing Shortage, CSU Cites Need for Additional Tenure–Track Faculty. As we discussed in Ensuring an Adequate Nursing Workforce: Improving State Nursing Programs (May 2007), beginning in the late 1990s, the state experienced a mismatch between employer demand for RNs providing direct patient care and the size of the RN workforce. In response, the state began expanding capacity by providing budget augmentations for pre–licensure nursing programs at CCC, CSU, and UC. Despite these efforts, the number of qualified applicants to nursing schools in California continued to far exceed the number of available slots, and numerous studies throughout much of the 2000s forecasted a persistent and long–term nursing shortage absent further enrollment expansions or other such strategies. In 2007, the CSU Chancellor’s Office formed an advisory committee and tasked it with exploring options for increasing nursing program capacity. The committee cited a lack of doctorally prepared nursing faculty as an impediment to further expanding nursing programs. (At the time, six universities in the state had nursing doctoral programs—five that offered a Ph.D. and one program, the privately operated University of San Francisco, that offered a DNP.) The advisory committee was further charged with studying whether it might be feasible for CSU to train future tenured/tenure–track nursing faculty by establishing its own doctoral program.

CSU Study Cites Several Advantages to Offering Its Own DNP. In 2008, the advisory committee released a study concluding that (1) more tenure–track faculty were needed to meet the current and projected demand for additional nurses in the state and (2) CSU had sufficient institutional interest and capacity to prepare more faculty by establishing a doctoral program in nursing. The CSU study acknowledged that, based on survey results, its nursing directors would prefer to offer a Ph.D. rather than a DNP. The committee recommended against pursuing a Ph.D., however, because (1) doing so would result in “significant competition” from the state’s Ph.D.–granting programs (including UC’s schools of nursing) and (2) previous attempts to develop joint CSU/UC doctoral programs in nursing “were unsuccessful.” The committee also noted that launching a Ph.D. program at CSU would require “significant growth” within nursing schools to boost research productivity among current faculty members and secure external funding to support that research. The DNP, by contrast, would not require as extensive of a research program for current faculty, would be shorter in length than the Ph.D., and likely would be attractive to nurse professionals seeking to advance their careers.

CSU Also Cites DNP as Way to Help the State Meet Higher Anticipated APRN Education Requirements. In addition to producing future nursing faculty to address the state’s nursing shortage, the CSU study pointed to AACN’s 2004 vote to support increasing education requirements for APRNs to a DNP by 2015. As the CSU study stated, “It is expected that by 2015, the doctoral degree for advanced practice nurses will be required for licensure.” To prepare for that anticipated new requirement, the CSU study argued that the segment could give the state a head start on meeting that requirement.

CSU Envisioned Having Two DNP Tracks—Education and Advanced Practice. The CSU study acknowledged that, as a clinical degree, the DNP is not designed to prepare nurses for teaching careers. To reorient its proposed DNP toward preparing nursing faculty, the study recommended creating two tracks within the program—one specializing in nursing education (emphasizing competencies such as curriculum design and development), and a second specializing in advanced clinical practice to prepare DNP–educated nurse practitioners and other APRNs.

CSU Encouraged a Collaborative Approach to Operating Its DNP Programs. The CSU study identified potential ways for CSU campuses to collaborate with each other on a DNP program so as to use physical and human resources efficiently. Based on interviews with nursing program directors in other states, the study identified a possible consortium approach in which campuses share faculty, facilities, and support. To reduce the need for physical space and provide better access to students (many of whom work full time and have family obligations), the CSU study also recommended that at least some courses be taught online. Finally, the study recommended that CSU begin with DNP programs at two or three campuses, with initial cohorts of ten students per campus and future enrollments based on “shifts in demand and resources.”

Statutory Requirements

Chapter 416 Authorized CSU DNP as an Exception to State’s Longstanding Master Plan for Higher Education. As described in more detail in the nearby box, California’s Master Plan delineates the graduate–level functions of CSU and UC, with CSU to offer master’s degrees and UC to offer both master’s and doctoral degrees. Chapter 416 makes an exception to this delineation for a limited, targeted purpose—to address the nursing shortage the state was experiencing. Specifically, Chapter 416 found that (1) California “faces an ever–increasing nursing shortage that jeopardizes the health and well–being of the state’s citizens,” (2) postsecondary institutions need to continue to expand nursing education programs to address that shortage, and (3) the state needs to produce additional faculty to teach such programs. Accordingly, Chapter 416’s primary purpose was to empower CSU to address the state’s nursing shortage by educating doctorally prepared, tenured/tenure–track nursing faculty. The legislative authorization was temporary—a pilot program with a specified sunset date—rather than a permanent authority. In authorizing CSU to offer an independent DNP, Chapter 416 set out a number of specific requirements regarding the purpose and funding of the new program. The next few paragraphs describe the main requirements.

Doctoral Education at UC and CSU

Master Plan Assigned Doctoral Education to University of California (UC), With Allowance for California State University (CSU) to Offer Joint Degrees. In 1960, the Legislature adopted California’s Master Plan for Higher Education and incorporated many of its provisions into statute. Among these provisions is the assignment of specific missions to the state’s public higher education segments. CSU was given primary responsibility for undergraduate and graduate education in liberal arts and sciences through the master’s degree. UC was given responsibility for undergraduate and graduate education through the doctoral degree, but was permitted to award joint doctoral degrees with CSU. The inclusion of joint doctorates in the final plan was a compromise between the two systems. Over the following decades, CSU developed dozens of joint doctoral degrees with UC as well as a private university (Claremont Graduate University).

Legislature Has Allowed CSU to Award a Few Independent Doctoral Degrees. Forty–five years after adoption of the Master Plan, the state authorized CSU to offer its first independent doctoral degree, the Doctor of Education Degree. Chapter 269 of 2005 (SB 724, Scott) was narrowly written as an exception to the Master Plan in recognition of the urgency of preparing more educational leaders. Since that time, the Legislature has approved three more independent CSU doctoral programs—each to address a specific issue. In 2010, the Legislature authorized CSU to offer a Doctor of Physical Therapy degree, which was in response to a 2009 decision by an accreditor to no longer accredit physical therapy programs at the master’s level. Also in 2010, the Legislature authorized CSU to offer the Doctor of Nursing Practice degree on a pilot basis. In September 2016, the Legislature authorized CSU to offer an independent Doctor of Audiology degree to address an identified shortage of audiologists in the state.

DNPs to Focus on Preparing Nursing Faculty. Chapter 416 requires the independent CSU programs to focus on preparing nurses to serve as faculty at colleges and universities. In addition to this primary focus, Chapter 416 permits the pilot programs to provide additional training for APRNs and nurse leadership. Regardless of the degree’s specific purpose, Chapter 416 requires CSU to design an educational program that nursing professionals can complete while working full time.

Campus, Program, and Enrollment Limits Placed on Pilot Programs. Chapter 416 authorizes CSU to establish a DNP program at up to three campuses, which are to be chosen by the Board of Trustees. In addition, Chapter 416 prohibits the three pilot programs from replacing or supplanting any CSU master’s degree nursing programs that were offered as of January 1, 2010—effectively disallowing CSU from converting an existing master’s program in nursing to a DNP. Furthermore, the legislation limits CSU to serving no more than a total of 90 full–time equivalent (FTE) students across the three campuses.

DNP Programs Not to Diminish Undergraduate Programs. Four requirements in the legislation aim to ensure that enrollment growth in DNP programs do not come at the expense of undergraduate programs. The requirements, which resemble provisions in the legislation authorizing the Ed.D. and Doctor of Physical Therapy programs at CSU, are: (1) enrollment is to be funded from within CSU enrollment growth levels as agreed to in the annual budget act; (2) state funding for each FTE student is to be at the agreed–upon marginal cost rate for CSU students; (3) DNP enrollments may not alter CSU’s ratio of graduate instruction to total enrollment, nor diminish growth in university undergraduate programs; and (4) CSU must provide initial funding from existing budgets, with legislative intent that CSU seek private funding or other nonstate funds for start–up costs.

Tuition Rates Not Specified in Legislation. Unlike the legislation authorizing CSU’s Ed.D. and Doctor of Physical Therapy programs, Chapter 416 does not include any requirements or limits on the tuition or fees charged to DNP students.

LAO Required to Evaluate Pilot Prior to Scheduled Sunset. Chapter 324 includes a requirement for CSU to provide specified information to the Legislature and Governor by March 2016, including program enrollment, completions, and costs. In addition, Chapter 324 requires CSU to report on whether its DNP graduates are positively impacting the state’s nursing shortage and the extent to which the pilot programs are “fulfilling identified state needs for training doctorally prepared nurses.” Chapter 324 then requires our office to consider this and other information and make recommendations on the future of the pilot. Unless addressed by further legislation, Chapter 416 prohibits CSU from enrolling any new students in the degree pilot programs after July 1, 2018.

Back to the TopFindings

Below, we present our findings regarding CSU’s implementation of DNP programs and compliance with the Chapter 416 requirements.

Programs

Chancellor’s Office Specified Policies and Procedures for New Programs. Once Chapter 416 was signed into law, CSU set out to implement the new DNP programs within 18 months. In November 2011, the CSU Chancellor issued an executive order outlining the policies and procedures for the planned DNP programs. The executive order and supporting documents emphasized the statutory requirements for the new doctoral programs and established minimum eligibility and graduation standards for students.

CSU Formed Two Consortia Programs Consisting of a Total of Five Campuses. In fall 2010, the CSU Chancellor’s Office issued a request for proposals to CSU campuses that were interested in piloting the DNP. A total of six campuses responded. The Chancellor’s Office grouped five of the applicants into two consortia—the Northern California Consortium (consisting of the Fresno and San Jose campuses) and the Southern California Consortium (consisting of the Fullerton, Los Angeles, and Long Beach campuses). The other campus (San Diego) subsequently withdrew its plan to implement the DNP. The Chancellor’s Office approved the two consortia and their member campuses in January 2011. The first cohorts in each program began their classes in fall 2012. The Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education formally accredited the southern consortium in November 2013 and the northern consortium in February 2014.

Each Consortium Has a Lead Campus, Shares Teaching Responsibilities. Each consortium has an administrative lead—the Fresno campus for the northern consortium and the Fullerton campus for the southern consortium. Students apply to one of the administrative lead campuses and, if accepted, are an official student of that campus. Each consortium also has a committee made up of the nursing program directors and DNP coordinators from the member campuses. The committees meet regularly to plan and make decisions on their program. Under CSU’s consortium approach, courses are taught by faculty from each of the member campuses and consortium members share responsibilities such as outreach, recruitment, and application reviews. Student support services (such as tutoring centers) generally are provided by the lead campus.

Programs Operate Year–Round. While Chapter 416 requires CSU to enable nurse professionals to earn a DNP while working full time, the legislation does not set expectations on the duration of the program. The Chancellor’s Office’s November 2011 executive order specified that the program is not to be longer than three calendar years in length. Both programs decided on a five semester–long program (spanning 21 months), with coursework extending throughout the summer. Students progress through these programs in cohorts. That is, all students entering a program in a given fall term take their courses together and are expected to complete the program together.

Program Use Online Technology to Deliver Instruction. Both programs have an online component. Instruction in the northern consortium is almost entirely online, with students meeting face to face with instructors and peers a few times per year. Instruction in the southern consortium is in–person (at the Fullerton campus) for the first three semesters. Courses in the final two semesters of the program are conducted primarily online.

Curriculum

Curriculum Includes Nursing Education Coursework but No Education Specialization. Because the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education determined that the DNP is to be a practice–oriented degree, CSU had to drop its original plans to create an education specialization. Instead, each CSU pilot program has one practice–oriented track that includes some coursework in curriculum development and teaching strategies.

Requirements for the Two Programs Largely the Same. Figure 3 shows the course requirements for the Northern and Southern California consortia programs. As the figure shows, course requirements are similar and each degree totals 36 units. (As the figure indicates, the Northern California consortium has an elective on nursing education, which adds two units to the degree for students who opt to take that course.) The Northern California consortium requires more courses but generally has fewer units per course.

Figure 3

Doctor of Nursing Practice Curriculum Similar for Two CSU Consortia

|

Northern California Consortium |

Units |

Southern California Consortium |

Units |

|

Biostatistics |

3 |

Biostatistics |

3 |

|

Epidemiology and Clinical Prevention |

3 |

Epidemiology and Clinical Prevention |

3 |

|

Evidence–Based Research and Practice |

6a |

Evidence–Based Research and Practice |

3 |

|

Diversity |

2 |

||

|

Health Care Information Systems and Technology |

3 |

Health Care Information Systems and Technology |

3 |

|

Health Care Policy |

2 |

Health Care Policy and Advocacy |

3 |

|

Leadership |

2 |

Leadership, Management, and Finance |

3 |

|

Finance |

2 |

||

|

Nursing Education—Curriculum Development |

3 |

Nursing Education—Curriculum Development |

3 |

|

Nursing Education—Evaluation |

3 |

Nursing Education—Instructional Design |

3 |

|

Nursing Theories |

2 |

||

|

Doctoral Project Development and Completion |

2 |

Doctoral Project Development and Completion |

9 |

|

Practicum—Clinical Setting |

3 |

Practicum—Clinical Setting |

3 |

|

Total Units Required |

36b |

36 |

|

|

aTaken as three separate classes of 2 units each. bOn top of the 36 required units, students have the option of taking a 2–unit course in Nursing Education—Evidence–Based Teaching. |

|||

Doctoral Projects a Central Feature of Curriculum. Students’ doctoral projects are the centerpiece of the DNP curriculum. Students are encouraged to identify a project topic as early as possible and approach each course in the context of their project. For example, students taking biostatistics are instructed to use the course to determine the appropriate statistical methods for their project. In addition, each program has independent study courses in which students are expected to work directly with their faculty chair to develop and complete their doctoral project. Because the DNP is considered a practice degree, the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education requires all DNP students to accrue at least 1,000 clinical hours. CSU’s “Practicum” course allows students to meet this requirement while earning units toward their degree by conducting research for their doctoral project at their workplace or other clinical setting. (CSU DNP students can apply to their DNP up to 500 clinical hours that they accrued in their master’s program.)

Applications, Admissions, and Enrollment

Applicants Must Meet Minimum Job and Academic Requirements. To apply to a CSU DNP program, students must (1) have a current RN license; (2) hold a master’s degree in nursing or a health–related field (such as public health or health administration); (3) meet minimum master’s degree grade point average (GPA) requirements (3.0 for the northern consortium, 3.5 for the southern consortium); (4) submit a specified number of letters of recommendation or professional references; (5) write a statement of purpose; and (6) complete an interview and writing sample, as requested. Applicants are scored and ranked based on their GPA and other factors. The average master’s program GPA for enrolled students is 3.8 out of 4.0.

Most Qualified Applicants Accepted for Admission. Figure 4 summarizes qualified applications, admissions, and enrollments for each of the two consortia programs. Overall, the two consortia admitted 88 percent of applicants for the first five cohorts, with admission rates for the cohorts ranging from 64 percent to 100 percent. Of the students admitted, 80 percent enrolled. Enrollment rates for the cohorts ranged from 68 percent to 89 percent.

Figure 4

Doctor of Nursing Practice Admission and Enrollment Rates

|

Qualified |

Admitted |

Admission |

Enrolled |

Enrollment |

|

|

Northern California Consortium |

|||||

|

2012 |

43 |

37 |

86% |

33 |

89% |

|

2013 |

30 |

30 |

100 |

26 |

87 |

|

2014 |

33 |

30 |

91 |

25 |

83 |

|

2015 |

36 |

32 |

89 |

24 |

75 |

|

2016 |

36 |

36 |

100 |

30 |

83 |

|

Average rate over period |

— |

— |

93 |

— |

84 |

|

Southern California Consortium |

|||||

|

2012 |

64 |

41 |

64% |

32 |

78% |

|

2013 |

44 |

41 |

93 |

35 |

85 |

|

2014 |

34 |

34 |

100 |

23 |

68 |

|

2015 |

29 |

29 |

100 |

22 |

76 |

|

2016 |

54 |

45 |

83 |

35 |

78 |

|

Average rate over period |

— |

— |

84 |

— |

77 |

|

Totals |

403 |

355 |

88% |

285 |

80% |

At Times CSU Has Exceeded the Statutory Enrollment Limit. As discussed in the previous section, Chapter 416 limits DNP “enrollment and maintenance” to no more than 90 FTE students across the pilot campuses. While CSU served a total of 45 FTE students in 2012–13 (the initial year of the pilot) and 88 FTE students in 2015–16, CSU exceeded the statutory limit in 2013–14 (112 FTE students) and 2014–15 (99 FTE students). (The Chancellor’s Office maintains that it understood Chapter 416’s enrollment limit to mean a combined 90 FTE students per cohort per year.)

Undergraduate Share of Enrollment Has Not Diminished. Because DNP enrollments are so small (100 FTE students represent less than three one–hundredths of 1 percent of total CSU enrollment), the new programs have had little effect on the undergraduate share of enrollment. In 2011–12 (the year prior to commencement of DNP programs), undergraduate and graduate enrollment accounted for 88.7 percent and 9.5 percent, respectively, of total enrollment. Since then, the undergraduate share has increased to 90 percent and the graduate share has dropped to 8.3 percent. (Postbaccalaurate students in teaching–credential programs make up between 1 percent and 2 percent of CSU enrollment.)

Student Characteristics

Students Mostly Women Working Full Time. Students enrolling in the CSU DNP programs typically are in their thirties or forties. Similar to the overall RN workforce, about 90 percent of students are women. Of the two programs’ five cohorts to date, 42 percent have been white, 26 percent Asian/Pacific Islander, 12 percent Latino, 9 percent African–American, and 11 percent Other/Decline to State. The vast majority of DNP students work full time as nurse professionals while enrolled in the program.

Students Motivated by Number of Factors. During our site visits to the two programs, students and alumni expressed a number of reasons for choosing to pursue a DNP. Since the DNP is not a requirement to practice, the decision to enroll in a program generally was not employer–driven. Rather, a number of students cited personal reasons and the opportunity to enhance leadership and critical–thinking skills as prime motivators. Several students mentioned they sought the DNP to gain a broader perspective on the nursing profession—to step back from day–to–day patient care and acquire more of a systems and organizational viewpoint. While all students had coursework in nursing theory and evidence–based practices as part of their master’s degree, many stated that the DNP offered opportunities to expand on this knowledge base and critically evaluate research and current protocols in their workplace. Several alumni remarked that the DNP gave them more confidence to assume a leadership role at work and that having a doctorate kept them at the “same level” as workplace colleagues who also had the title of “doctor” (such as physicians, pharmacists, and physical therapists). Finally, multiple students remarked they liked CSU’s education component. Even if they opted not to teach in a postsecondary institution after graduation, DNP students felt the nursing education courses helped them become better teachers of health education to patients and colleagues.

Student Completion Rates

Graduation Rates Are High. To graduate with a DNP degree, students must successfully complete all coursework, write and orally defend a doctoral project, and—if they did not have it already—obtain national certification in an APRN role (such as nurse practitioner) or non–APRN role (such as a nurse administrator). To date, three cohorts of DNP students have enrolled and graduated. Of the 174 students who enrolled in the fall 2012 through fall 2014 cohorts, 162 (93 percent) have graduated. The attrition rate for the first three cohorts is 7 percent (12 students out of 174).

Job Placement

Some Graduates Teaching at Postsecondary Institutions—Though Largely in Nontenure–Track Positions. As shown in Figure 5, of the 162 CSU DNP graduates to date, 37 (23 percent) serve as faculty at CSU. Most of these faculty (29) are in nontenure–track lecturer positions. Seventeen of these faculty were already lecturers at CSU when they enrolled in the DNP program. The remaining eight faculty hires have tenure–track positions at CSU. Of these eight tenure–track hires, three were already lecturers at CSU when they enrolled in the DNP program. The other five hires had not previously worked at CSU. In addition to the 37 CSU faculty hires, 18 DNP graduates have been hired as faculty at other colleges and universities in the state. Data indicate that no more than 7 of these 18 DNP graduates are in faculty positions that require a doctorate. Thus, out of 162 DNP graduates to date, no more than 15 (9 percent) likely are in a tenure–track position requiring a doctorate.

Most Clinicians and Administrators Stayed With the Same Employer Upon Graduating. Based on CSU surveys of the first two graduating cohorts, students generally have stayed in their same position and with their same employer upon earning their DNP degree. Several administrators who have maintained their same position, however, indicate that they have expanded responsibilities at work, and a number of administrators and clinicians report that they are now speaking nationally on their doctoral projects and other areas of expertise.

Student Costs and Aid

Students’ Educational Costs Total About $40,000 for the Program. The CSU Board of Trustees establishes systemwide tuition and fee levels for all programs. The systemwide tuition rate for the DNP program in 2016–17 is $7,170 per semester—the same rate as when the program began in 2012–13. This amount equals $14,340 for the academic year and $35,850 for the five semester program. In addition to the systemwide tuition, campuses set campus fees required of all students. Annual campus fees for DNP students total about $1,000 (or about $2,000 for the full program). Book and supply costs for DNP programs average about $900 per year (or about $1,800 for the program). Altogether, total educational costs for a DNP degree are about $40,000.

Loans and Grants Available. Unlike typical CSU students, all DNP students have master’s degrees and virtually all work full time. The two primary sources of financial aid for DNP students are federal student loans and campus grants from a 20 percent set–aside from DNP tuition revenues. CSU reserves these campus grants for nursing students they define as financially needy. In addition, several scholarships and fellowships are available to offset students’ costs. In 2014–15, just over 60 percent of DNP students received a federal loan, which averaged $17,760 per borrower that year. Forty–four percent of students received a grant or scholarship, with awards averaging $11,324. In addition, since the inception of the DNP program, ten students have received education loans through the Chancellor’s Doctoral Incentive Program. This program, which is funded with state lottery monies, forgives loans of doctoral students studying at universities throughout the country who take full–time teaching jobs at CSU upon earning their degree.

Institutional Costs and Funding

Programs Largely Supported by Tuition Revenue. Figure 6 shows program revenues and costs for 2014–15, as reported by the consortia to the CSU Chancellor’s Office. Gross tuition revenues from DNP students totaled $943,000 at the Northern California consortium and $1.2 million at the Southern California consortium. Campus operating funds (comprising primarily a mix of state General Fund monies and redirected tuition from non–DNP CSU students) were about $19,000 at the Northern California consortium and about $194,000 at the Southern California consortium. The CSU Chancellor’s Office notes that the total amount of campus operating funds supporting these programs may be understated, however, because the amounts in Figure 6 generally do not include campus funding for indirect activities (such as back–office staff in human resources, accounting, and information technology).

Figure 6

Doctor of Nursing Practice Program Budgets

2014–15

|

Northern California |

Southern California |

|

|

Funding |

||

|

Gross tuition revenue |

$924,930 |

$1,025,310 |

|

Campus operating funds |

19,005 |

194,449 |

|

Totals |

$943,935 |

$1,219,759 |

|

Expenditures |

||

|

Instructional faculty |

$624,973 |

$599,104 |

|

Administrative staff |

181,884 |

190,642 |

|

Financial aid—grants and waivers |

99,062 |

209,807 |

|

Other operating expenses |

38,016 |

220,206 |

|

Totals |

$943,935 |

$1,219,759 |

|

Full–time equivalent (FTE) students |

55.5 |

43.9 |

|

Program spending per FTE student |

$17,008 |

$27,785 |

Costs and Per–Student Spending Varies by Program. Comparing costs between the two programs is difficult because of differing accounting practices. For example, library and tutorial services are included in the Southern California consortium’s budget, whereas the Northern California consortium covers these costs from within Fresno State’s overall university budget. Nevertheless, for both programs, salaries and benefits for DNP faculty and administrators account for the largest expense. The second largest costs are university grants, which subsidize financially needy DNP students’ tuition. Overall, the Northern California consortium reports program spending of $17,000 per FTE student in 2014–15, whereas the Southern California consortium reports program spending of about $27,000 per FTE student. A variety of factors, including differences in the sizes of student cohorts and faculty compensation levels, explain these differences in funding per student.

Start–Up Costs Funded by CSU. Both programs reported having start–up costs. Start–up costs included release time for faculty for program and course development and costs for consortia meetings, promotional materials, and supplies. Consortium members generally covered these start–up costs using general–purpose funds allocated by campus administration. The Chancellor’s Office reports that external sources, such as foundation grants, were not pursued due to the rapid timeline CSU followed to implement the new programs.

Back to the TopLAO Assessment and Recommendation

Below, we offer our assessment of the CSU DNP pilot and make a recommendation regarding its extension.

State No Longer Facing Primary Problem That CSU DNP Was Designed to Address. The Legislature supported the pilot DNP program at CSU to address the state’s nursing shortage. Shortly after Chapter 416 was signed into law, however, the nursing shortage in the state eased considerably. According to the Board of Registered Nursing and University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) labor experts, this is due mainly to the significant expansion of nursing enrollments and graduations that occurred between 2001 and 2010. (Please see the nearby box for an explanation of how the state closed the gap between nursing supply and demand.) The Board of Registered Nursing and UCSF currently report that overall the state’s nursing labor market is “fairly well balanced.” Moreover, the supply of RNs is forecasted to match demand reasonably well through 2035, assuming the state continues to produce a stable supply of new nursing graduates each year. As a result, the state does not need to rapidly expand the number of nursing enrollments and hire large numbers of new faculty as was assumed at the time Chapter 416 was enacted.

State Successfully Addressed the Nursing Shortage

State Faced Nursing Shortage Throughout the 2000s. Beginning in the 1990s, health care employers indicated that the size of the nursing workforce was insufficient to adequately staff health care facilities—particularly hospitals, which are statutorily required to maintain minimum nurse–to–patient ratios. Despite paying higher wages and encouraging—and in some cases requiring—existing staff to work overtime, the state continued to experience a gap between supply of and demand for Registered Nurses (RNs) into the 2000s.

State Responded to Shortage by Expanding Capacity in Nursing Programs. The Legislature responded to this nursing shortage in a number of ways, most notably by providing targeted funding to the state’s public higher education segments to expand pre–licensure nursing enrollments. As a result of these and other factors (including an increase in the number of private colleges launching nursing programs), the number of students graduating with an RN license more than doubled during the 2000s—from about 5,100 graduates in 2000–01 to 10,600 graduates by 2010–11.

Nursing Labor Force in Good Shape Overall. According to the latest forecast from the Board of Registered Nursing and University of California, San Francisco, the large number of nursing graduations in the state (which has held reasonably stable at about 11,000 per year) likely is sufficient to ensure an adequate nursing workforce in the state for decades to come. Some hospital officials still report difficulty, however, with recruiting experienced RNs for certain specialized positions and attracting nurses to work in certain regions of the state (such as the Inland Empire and rural areas).

CSU Continues to Report Ongoing Difficulty With Regular Nursing Faculty Recruitment . . . Though the end of the state’s nursing shortage no longer meant that CSU had to further build out nursing enrollments and hire large numbers of new faculty, CSU still has vacant nursing faculty slots to fill each year, primarily due to retirements and turnover. Even faced with these regular hiring needs, CSU campuses report considerable difficulties with recruiting tenure–track faculty. For example, the Chancellor’s Office recently queried three CSU nursing programs concerning their ability to hire tenure–track faculty. In 2015–16, these programs advertised for a total of eight tenure–track positions, but had to cancel six of these searches for lack of a sufficient pool of candidates. CSU notes, “The difficulties in hiring tenure–track nursing faculty experienced by these three campuses provides a snapshot of what typically occurs in the other 16 nursing campuses.”

. . . But Only a Small Number of DNP Graduates Helping CSU With Regular Hiring Needs. As data from the previous section of this report show, the pilot DNP program has produced only a few CSU tenure–track nursing faculty. Most notably, even though CSU routinely has open positions go unfilled, to date only 8 of 162 DNP graduates have accepted a tenure–track position with CSU. CSU apparently is even having difficulty converting its “home grown” students into tenure–track positions—of 20 DNP graduates that were CSU lecturers when they initially enrolled in the program, just 3 have taken tenure–track positions. (The other 17 DNP graduates have retained positions as CSU lecturers.)

Increasing Compensation Levels More Direct Way for CSU to Address Ongoing Faculty Recruitment Challenges. The primary reason given by CSU for its ongoing difficulty attracting tenure–track nursing faculty is the relatively low salaries that such faculty receive at CSU compared with what nurse clinicians and administrators earn. In 2014, the average starting salary for entry–level, tenure–track nursing faculty positions was about $75,000. (In 2016, the average starting salary is up to about $80,000.) By contrast, the Board of Registered Nursing reports that the average annual income for RNs with an associate or bachelor’s degree was about $90,000 in 2014. Advanced practice clinicians such as nurse practitioners earned an average of $105,000 in 2014 and senior nursing administrators averaged more than $150,000. Like other educational entities in the state, CSU already has the power to pay differential salaries based on discipline. For example, the starting salary for CSU tenure–track faculty is more than $10,000 higher in nursing departments than in history departments (and about $25,000 lower in nursing departments than in business departments). A more direct way for CSU to confront its faculty recruitment problem would be to pay more competitive salaries. CSU nursing programs also could mitigate their hiring problems by modifying somewhat the proportion of overall faculty openings that are tenure–track. As mentioned earlier, campuses already have discretion on the mix of the nursing faculty that is tenured/tenure–track versus master’s–prepared lecturers.

For the Most Part, Accreditation Expectations About APRN Training Have Not Come to Fruition. As noted earlier, CSU also justified an independent DNP program based on its expectation that the degree would soon become a requirement for APRNs. With the future exception of nurse anesthetists, however, accreditors and licensing bodies continue to require APRNs to have a master’s (rather than doctoral) degree in nursing. Based on research, the master’s appears to be the appropriate entry–to–practice degree for nurse practitioners and other APRNs. Numerous studies demonstrate that master’s–prepared APRNs have historically functioned effectively in health care settings and no evidence to date suggests that DNP–prepared APRNs deliver better patient care and outcomes than their master’s–prepared counterparts.

Other Viable DNP Options for Students. As noted earlier, the DNP is a relatively new degree that has grown rapidly across the country. Whereas only three DNP programs were operating in 2004, in 2015 the AACN identified nearly 300 such programs—many of them online—across 48 states. In California, the number of DNP programs has increased from one in 2006 (at the University of San Francisco) to ten today (including the two CSU pilot consortia). In addition, three UC campuses (San Francisco, Irvine, and Los Angeles) are seeking to offer DNP degrees by 2018. The UCSF and UC Irvine programs would be offered primarily online (with some occasional face–to–face meetings) and be fully fee–supported. Whereas UCSF is planning a post–master’s program aimed at currently practicing APRNs, UC Irvine is proposing to have two tracks. Track One would be a post–bachelor’s program for RNs seeking to become a DNP–prepared nurse practitioner. Track Two would be a post–master’s program along the lines of CSU’s current pilot. UCLA, meanwhile, is planning a post–master’s, primarily face–to–face program that also would be fully fee–supported. UCSF has formally approved the DNP proposal and is awaiting a decision by the UC system. UC Irvine’s and UCLA’s DNP proposals are undergoing campus review, with a goal to obtain system approval by spring 2017. In addition to these three proposals, UC Davis is considering offering a DNP degree.

Granting Permanent Authority to Award Independent Doctoral Degree Undermines Master Plan and State’s Goals. In 1960, California adopted a framework intended to guide the state through the ensuing decades of intense demand for college education. Recognizing the potential for what it called “unhealthy competition” among the higher education segments, the Master Plan assigned distinct missions for each of the public segments. The assigning of distinct missions has been widely regarded as one of the most important and valuable elements of the Master Plan—helping to: justify state support for two extensive public university systems, impede mission–creep among institutions, contain growth in costs, and facilitate postsecondary access for all eligible students. To promote these key priorities, the Legislature’s default has been to maintain CSU’s traditional role unless compelling state workforce needs dictate otherwise. Absent such special circumstances, granting permanent authority to CSU to offer independent doctoral education weakens the state’s pursuit of mission differentiation, coherence, and coordination.

Recommend the Legislature Allow CSU Pilot to Sunset. Chapter 416 was authorized during a period when the state forecasted a growing shortage of RNs and believed that additional faculty would be needed to significantly expand nursing program enrollments. The legislation also was authorized at a time when CSU and others believed that the DNP would become a required degree for APRNs by 2015. Given a nursing shortage no longer exists, the DNP has not become the required degree for APRNs, an increasing number of DNP programs (including UC programs) are available to students, and the Legislature has a strong and longstanding preference for the delineation of functions as laid out in the Master Plan, we recommend the Legislature allow Chapter 416 to sunset. To the extent CSU nursing programs continue to have difficulty filling faculty vacancies, CSU already has other, likely more effective, options at its disposal such as making nursing faculty salaries more competitive with the industry and changing the mix of faculty positions that are tenure– and nontenure–track (lecturers).