Series

Revisiting the Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund Insolvency

Update 6/13/17:

Post 1 updated to reflect estimates in the 2017-18 May Revision.

Update 1/20/17:

Post 1 updated to reflect estimates in the 2017-18 Governor's Budget.

Budget and Policy Post

September 30, 2016Revisiting the Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund Insolvency

Potential Actions to Improve the Solvency of the State’s Unemployment Insurance (UI) Trust Fund

This post is the last in a series of four posts related to California’s UI program. The previous posts reviewed the current condition of the UI trust fund and how it may change in the near future, provided context on who pays UI taxes and how much they pay, and assessed the extent to which the UI trust fund is prepared for the next economic downturn. This final post looks at potential steps the Legislature could take should it wish to increase reserves in the trust fund as a means to address the fiscal impacts of the next economic downturn.

The other posts in this series can be accessed using the nearby menu.

Background

UI Program Assists Unemployed Workers. As described in previous posts, the UI program provides weekly benefits, funded through payroll tax contributions paid by employers, to workers who have lost their jobs through no fault of their own. Weekly UI benefits are intended to replace up to 50 percent of a claimant’s prior earnings, referred to as the “wage replacement rate,” subject to a maximum of $450 per week, for up to 26 weeks.

UI Program Is Financed Through Employer Tax Contributions. Employers pay both state and federal UI payroll taxes. State UI taxes are deposited into the state’s UI trust fund to pay for benefits to unemployed workers. State UI tax rates are determined in accordance with a series of rate schedules laid out in state law that generally require higher rates, up to a statutory maximum of 6.2 percent, when the condition of the UI trust fund is poor, meaning that it has a low level of reserves (as might occur following a recession), so that the fund’s reserves might be replenished. When the trust fund reserves are larger, state law provides that schedules with lower rates be used. Federal UI taxes are typically used to pay for certain costs other than state UI benefit payments, such as program administration; however, as described in a previous post, federal UI taxes may be increased to pay off federal loans received by a state to allow benefits to be paid when the state’s trust fund is insolvent. California employers are currently subject to increased federal UI taxes for this reason. Both state and federal UI taxes are determined by applying different state and federal UI tax rates to a base of each employee’s first $7,000 in annual wages, referred to as the “taxable wage base.” We note that federal law does not allow a state to have a taxable wage base lower than $7,000. California is one of three states that sets the taxable wage base at the federal minimum.

UI Trust Fund Became Insolvent in Last Recession. As described in our last post, state UI programs are traditionally intended to be countercyclical by raising above-average revenues during periods of economic growth in order to pay for above-average benefits during periods of economic contraction. However, due to many factors, including prior legislative action to increase UI benefits without changes to employer taxes and significantly elevated levels of unemployment during the last recession, the state’s UI trust fund reserves ran out in 2009. This resulted in the need for federal loans to continue benefit payments. These loans are projected to be repaid (meaning the trust fund will again have a positive reserve balance) sometime in 2018. However, depending on the timing and severity of the next recession, the trust fund may not build sufficient reserves and risks returning to insolvency in a future economic downturn.

UI Benefits Likely to Be Paid Regardless of Trust Fund Condition. If the Legislature takes no action to build larger reserves and the trust fund returns to insolvency in a future recession, federal loans would be available (at the state’s option) to continue the payment of benefits. These loans would require interest payments and may shift some of the cost of financing the UI system away from employers whose employees receive relatively greater benefits to employers whose employees receive relatively fewer benefits. This is because increased federal UI taxes used to pay off loans are applied equally to all employers without regard to the level of benefits received by employees. Alternatively, the Legislature could take action to build larger reserves and reduce the risk of returning to insolvency in the future. In what follows, we describe one example of the kinds of steps the Legislature could take should it wish to increase UI trust fund reserves.

Legislative Action Would Be Required to Increase UI Trust Fund Reserves

Building Larger Reserves Would Require Permanent Changes to Increase Revenues, Reduce Benefits, or a Combination of Both. In any given year, the change in the UI trust fund reserve balance depends on the difference in tax revenues collected and benefits paid out. In years of economic contraction when above-average total benefits are claimed, the cost of benefits typically exceeds the amount of revenues generated, drawing down the reserves. In years of economic growth, revenues raised should ideally exceed the total cost of benefits paid, building up reserves. In order to build larger UI trust fund reserves, the Legislature would need to change current law to increase employer tax contributions, decrease UI benefits, or some combination of both. These actions would increase the amount by which revenues exceed benefit payments during periods of economic growth and reduce the amount by which benefit payments exceed revenues during periods of economic decline, allowing trust fund reserves to build more quickly.

Adequate Reserve Level Depends on Expectations for Future Benefit Costs. As described in our last post, the UI trust fund reserves projected to be accumulated in the next several years risk being insufficient to cover benefits in a future recession. However, determining a target level of reserves that would with certainty avoid the need for federal loans in the future is not straightforward. This is because the needed level of reserves depends on expectations about future benefit costs and how they may change during significant economic downturns, and the timing and severity of future recessions are very difficult to predict. Tying reserve targets to benefit costs observed during past recessions, as described below, is one reasonable approach to determining a trust fund reserve target.

Average High Cost Multiple (AHCM) Provides Useful Benchmark When Considering Reserve Targets. The AHCM essentially measures the number of years the UI trust fund can pay benefits at levels observed in prior recessions without any revenues coming into the fund. A higher AHCM indicates that the trust fund could support recession-level benefit payments for a longer period of time and is therefore more prepared to weather a recession. The U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) has concluded that an AHCM of 1.0, or a reserve sufficient to pay for an entire year’s worth of recession-level benefits with no revenues, is the minimum acceptable level of solvency for a state trust fund. (In a typical recession the trust fund would receive some revenues, although less than in years of economic growth due to decreased taxable wages. However, the effects of a major recession would stretch across multiple years.) We note that the DOL’s choice of an AHCM of 1.0 as its reserve target is, on some level, an arbitrary one. As described later, reserve targets for California other than an AHCM of 1.0 could reasonably be chosen.

One Example of Possible Legislative Actions to Increase Reserves

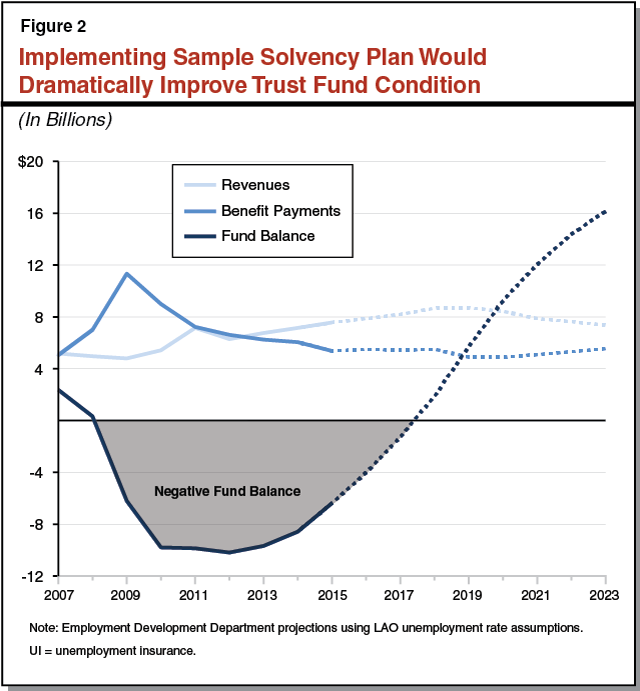

Features of a Sample Solvency Plan. Below, we provide an example of the kinds of actions the Legislature could take to increase trust fund reserves, using an AHCM of 1.0 as a sample reserve target. The specific actions in the sample plan, listed in Figure 1, include both tax increases and benefit reductions and are roughly based on a sample plan we presented in 2011. Below, we show Employment Development Department (EDD) projections, based on assumptions provided by our office, for how implementing the sample plan could affect trust fund reserves. For these projections, we assumed that the plan would be implemented beginning in 2019, the first year that employers would not be making extra federal UI tax payments as the current loans would be paid off. We make this assumption because implementing the solvency plan earlier would likely result in some overlap of increased state UI taxes (because of the solvency plan) with increases in the federal UI tax (to pay off the remaining federal UI loans that are currently outstanding) that would still be in effect. We further assumed, given the difficulty of anticipating the timing and severity of future recessions, that levels of unemployment would be declining or flat (no recession) for the foreseeable future. Finally, we did not assume that the state takes any additional action, beyond the changes described in Figure 1, to accelerate the repayment of current federal loans.

Figure 1

Features of the Sample Solvency Plan

|

|

|

|

As Long as the State Continues to Grow and Has Low Unemployment, Implementing Sample Plan Could Bring Trust Fund to Federal Reserve Target in 2023. As shown in Figure 2, EDD’s projections show that implementing the sample solvency plan in 2019 would increase state UI tax revenues as the federal UI tax increases end, resulting in projected reserves of about $16 billion by 2023. This reserve level roughly corresponds to an AHCM of 1.0, consistent with the federal DOL target and well positioning the trust fund to weather a major future recession. As noted in previous posts, there is a good chance that economic growth could stall and unemployment rise before 2023. Should a recession occur, trust fund reserves would be lower than displayed here.

Meeting DOL Reserve Expectations Is Not Mandatory. The example provided above is based on a trust fund reserve target equivalent to an AHCM of 1.0, DOL’s minimum acceptable level of reserves. However, we note that meeting the DOL reserve target is not mandatory. There is no direct penalty for states that maintain reserves at an AHCM below 1.0. (Only 18 states achieved this target as of January 2016.) While achieving the DOL’s reserve target is one requirement for states to obtain short-term (up to nine months) interest-free federal UI loans, we note that states that meet this target are much less likely to require federal loans in any event, decreasing the significance of this benefit.

Legislature Can Choose Its Own Reserve Target. While the DOL reserve target is a helpful benchmark, other reserve targets could reasonably be chosen. Historically, an AHCM of 1.0 is a high target for California—the last time this level of reserves was reached was 1990. The Legislature could choose a lower reserve target that would require more modest tax increases and/or benefit reductions. For example, the state had an AHCM of around 0.75 prior to the 2001 benefit increases. This lower level of reserves would still represent a significant improvement over the level of reserves that could be reached by 2023 if no action is taken (an AHCM of about 0.25).

Legislature Has Many Options to Consider

Under Current Law, UI Benefits Likely to Be Paid Regardless of Trust Fund Condition. As described in previous posts, the state’s UI trust fund may return to solvency in coming years, but risks not building sufficient reserves to cover the cost of UI benefits over the long term. If the Legislature takes no action to build larger reserves and the UI trust fund returns to insolvency in a future recession, federal loans will be available to continue the payment of benefits. Any future loans, if the Legislature takes no action to repay them, will ultimately be repaid by employers. Not taking action to build larger reserves and relying on federal loans in the future as necessary avoids tax increases and/or benefit reductions in the near term, but also could result in future interest costs (which, in the case of the current federal loans, are being paid by the General Fund). Possible future increases in federal UI taxes to repay federal loans could shift more of the cost of financing the UI system to “low-cost” employers whose employees receive a relatively smaller share of total UI benefits.

Larger UI Trust Fund Reserves Can Be Achieved in Various Ways. Should the Legislature wish to build larger reserves that would be more likely to sustain the payment of UI benefits through future recessions, it will be necessary to choose a reserve target and enact some combination of revenue increases and/or benefit reductions to allow reserves to accumulate more quickly while the economy is experiencing moderate growth to prepare for the next downturn. In this post, we present just one example of how a reserve target could be established and a set of changes that could be enacted to work toward achieving that target.