Related content . . .

September 22, 2016

California Community Colleges:

Second Progress Report on the Student Success Act of 2012

- Introduction

- Background

- Findings

- LAO Assessment of Implementation to Date

- Recommendations

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

Legislature Increases Focus on Student Outcomes at California Community Colleges (CCC). The Legislature has taken several actions to address low student completion rates at the community colleges. In 2010, it enacted legislation directing the CCC Board of Governors (BOG) to adopt a comprehensive plan for improving student outcomes. Toward this end, the board created a task force and, in 2012, endorsed the task force report, which contained 22 recommendations designed to improve student achievement. Chapter 624 of 2012 (SB 1456, Lowenthal) codified four of these recommendations, including one to establish the Student Success and Support Program (SSSP). This program provides various intake and guidance services to students and requires colleges to coordinate these services with a separately required “Student Equity Plan” (SEP), whose purpose is to identify and close access and achievement gaps among demographic groups.

Legislature Calls for Progress Reports. Chapter 624 called for our office to complete biennial progress reports, beginning in 2014. This is the second biennial report. In this report, we focus primarily on how colleges have used significant state funding increases for SSSP and student equity.

Key Findings and Assessment

Systemwide and College Efforts to Implement SSSP and Student Equity Generally Are Consistent With Intent of Legislation. In our review, we found that both the CCC Chancellor’s Office and colleges have made significant progress in implementing Chapter 624. Most notably, colleges have: implemented new academic standards for BOG fee waivers; established policies that require students to complete certain core student support services (such as assessment, orientation, and education planning) to receive and maintain priority registration; and hired more than 3,000 full–time equivalent student support staff, including additional counselors and instructors.

Majority of Newly Enrolled Students Are Receiving Some SSSP Services. A slight majority of students newly enrolled in fall 2015 received assessment and placement services, a near majority received orientation and education planning, and more than 40 percent received other counseling services by the end of the fall term. Though completion rates appear to have risen somewhat between fall 2014 and fall 2015, the latest rates remain low.

SSSP and Student Equity Activities Vary Across Colleges. Many colleges used SSSP funds to expand existing outreach programs and add online orientation services. Other common SSSP activities included expanding the use of multiple measures for assessment, hiring student “ambassadors” to help new students navigate the required matriculation services, and increasing the availability of counseling services. Common student equity activities included expanding existing student support services such as tutoring and supplemental instruction, implementing peer mentoring programs and learning communities for underrepresented minorities, and offering equity–focused professional development for faculty and staff.

Progress Has Been Uneven, Could Be Improved. We found that some colleges are not spending their SSSP and student equity funds strategically, and many CCC students still do not complete all mandatory SSSP services in the specified time frames. Specific shortcomings we identified include:

- Granting Priority Registration Has Had Limited Effect. The recovering economy and several years of notable enrollment growth funding have meant students generally can enroll in desired courses without priority registration. As a result, priority registration provides little extra encouragement for students to complete required core activities.

- Equity Gap Analysis Has Two Main Problems. Under current guidelines, a college can get conflicting answers as to whether an equity gap exists for a particular group depending on which methodology the college chooses. In addition, a college may misidentify inequities, such as finding that affluent students are disadvantaged because they are underrepresented at a college.

- Reporting Lag Hampers Legislature’s Ability to Monitor Results. CCC’s online Student Success Scorecard displays systemwide and college outcomes for a cohort of entering students six years after initial enrollment. Accordingly, the scorecard would not document any results for students who entered in fall 2014 until 2020–21.

- Course Alignment With Student Education Plans Still Needs Work. In our 2014 progress report, we identified the alignment of course offerings with student education plans as one of three key areas needing focused attention. CCC has made little progress in this area.

Recommendations

We make five recommendations designed to improve the implementation and evaluation of SSSP and student equity moving forward. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature:

Strengthen Requirement for Students to Complete Assessment, Orientation, and Education Planning. We recommend the Legislature direct the BOG to revisit how to make these services mandatory for students, while mitigating any disproportionate impact on groups of students.

Standardize Equity Gap Analyses. We recommend the Legislature direct the Chancellor’s Office to identify a consistent way of measuring disparities for each of the specified student outcomes and provide additional training for campus personnel on analyzing disparities.

Require a Special Three–Year Student Success Scorecard. This scorecard would permit the Legislature to evaluate outcomes prior to 2021, when the regular six–year scorecard would become available. We recommend the Chancellor’s Office release the three–year scorecard by October 2017 and include data for the cohorts entering in 2014–15, as well as in 2013–14 and 2012–13 for comparison. We further recommend that the three–year scorecard provide outcome data disaggregated by whether students received each of the core SSSP services.

Promote Evidence–Based Practices in SSSP and Student Equity. We recommend the Legislature direct the Chancellor’s Office to identify, by October 1, 2018, a list of practices shown to be effective in improving student success and reducing equity gaps in community college settings. Over time, the state could direct the use of SSSP and student equity funds toward effective practices.

Require Data on How Course Offerings Match Students’ Education Goals. We recommend the Legislature direct the Chancellor’s Office to identify, by January 1, 2018, strategies to monitor and improve the alignment of course offerings with students’ goals, as documented in their education plans.

Introduction

Legislature Required California Community Colleges (CCC) to Develop Systemwide Improvement Plan. Ongoing concerns about low student completion rates prompted the Legislature to pass Chapter 409 of 2010 (SB 1143, Liu). Chapter 409 directed the CCC Board of Governors (BOG), the CCC’s state–level governing body, to adopt and implement a comprehensive plan for improving student outcomes. To help develop the improvement plan, the legislation required the BOG to create a task force. In 2011, the Student Success Task Force released a report containing 22 recommendations designed to improve student outcomes. In early 2012, the BOG endorsed the report. The task force noted that some recommendations required state policy and budget actions, some required new BOG regulations, and others involved individual colleges taking certain actions, such as disseminating best practices.

Legislature Passed Student Success Act in 2012. Chapter 624 of 2012 (SB 1456, Lowenthal) codifies four key recommendations from the task force report. Specifically, Chapter 624: (1) requires the BOG to establish policies around mandatory assessment, orientation, and education planning for incoming students; (2) permits the BOG to set a time or unit limit for students to declare a major or other specific educational goal; (3) authorizes the BOG to establish minimum academic standards for financially needy students who receive enrollment fee waivers; and (4) establishes the Student Success and Support Program (SSSP), which provides various intake and guidance services to new and continuing students. As part of this new program, colleges are required to develop a SSSP plan that coordinates with a separately required “Student Equity Plan” (SEP), whose purpose is to analyze and identify strategies for closing enrollment and achievement gaps among historically underrepresented and other demographic groups.

Chapter 624 Requires LAO to Submit Biennial Reports. Specifically, the LAO is to report on:

- CCC’s implementation of Chapter 624 to date at the systemwide and college levels, with recommendations on how implementation could be improved.

- The impact of Chapter 624 on student academic progress and program completion, disaggregated by various demographic groups.

- Whether the provisions of Chapter 624 have been implemented consistent with legislative intent, and the extent to which students have access to counseling services.

- Overall progress on implementation of the task force’s other recommendations.

Second LAO Report Focuses on Key Developments Since 2014. At the time of our first progress report (July 2014), the BOG had adopted several regulatory changes that were about to go into effect and the Legislature had just provided the CCC system with the first of several large funding increases for SSSP and other CCC student success–related programs. This second report focuses primarily on how colleges have used significant state funding increases for student success initiatives. This report also assesses the progress made by CCC in addressing task force recommendations that our 2014 report had identified as needing more sustained focus. As many student success efforts remain in their early years of implementation, determining their impact on student outcomes remains premature. We plan to analyze these outcomes in future progress reports.

Organization of Report. Below, we provide background on SSSP, student equity, and other CCC student success programs. In the background section, we consider the effects of recent actions taken by the BOG, including setting minimum academic standards for fee waivers and establishing new policies for registration. We next discuss implementation of student success and equity programs. We conclude with an assessment of implementation to date and offer recommendations for legislative consideration.

Back to the TopBackground

This section describes SSSP and student equity, and summarizes state funding for these and other CCC student success programs.

Former Matriculation Program Recast as SSSP. The Legislature created the Matriculation Program in 1986 to ensure CCC students received certain support services to help them set and achieve an educational goal. “Core” services included assessment and placement, new student orientation, counseling, education planning, and at–risk follow–up services. Figure 1 defines each of these core services. Colleges received Matriculation Program funding based on their enrollment. Chapter 624 renamed the Matriculation Program the SSSP and maintained its focus on the same set of core support services. Unlike the Matriculation Program, however, SSSP directed the BOG to adopt new policies requiring students to complete assessment and placement, orientation, and education planning. (Certain “exempt” students, such as those students with an associate degree or higher, are not required to complete these services.)

Figure 1

Core Student Success and Support Program Services

|

Assessment and Placement. Activities to place students in appropriate English, math, and/or English as a Second Language classes based on test results and other measures, such as educational background and performance as well as need for special services. |

|

New Student Orientation. Activities to inform new students of college programs, student support services, and academic expectations, and provide other useful information. |

|

Counseling. Activities to provide information, guidance, and social support to help students identify and achieve their academic, career, and other goals. |

|

Education Planning. Activities to help students identify their academic and career goals and select a course of study. There are two types of education plans: (1) abbreviated education plans, which identify a preliminary academic goal and courses for one or two terms; and (2) comprehensive education plans, which cover all remaining terms. (Education planning is a subset of counseling.) |

|

At–Risk Follow–Up Services. Activities to support students who are facing academic probation or dismissal, are enrolled in remedial courses, or have not developed an education plan. Includes academic and career counseling, probation workshops, and referral to other student support services. |

Colleges Receive SSSP Funding Based Mainly on Services Provided. Chapter 624 requires the BOG to develop an allocation formula for SSSP funds that reflects, at minimum, the number of students eligible to receive core services at each college and the number who receive them. The BOG developed separate, but very similar, formulas for SSSP credit and noncredit programs. Because the credit component accounts for 94 percent of total funding, we describe the credit SSSP formula here. The adopted allocation formula, effective beginning in the 2015–16 academic year, distributes 60 percent of funds based on the number and types of services provided. Another 30 percent is based on student enrollment, and 10 percent is for a uniform base grant to each college. Within the 60 percent component, the formula weights the various services to reflect their costs. A comprehensive student education plan, for example, generally is more expensive to provide than an orientation, initial assessment, and abbreviated education plan. Accordingly, the formula allocates more for comprehensive education plans than the other services. To provide the necessary data for allocations, colleges track the number and types of services provided to each student, and submit this information to the CCC Chancellor’s Office. Chapter 624 also requires colleges to match state SSSP funds with local funds. (See the box below regarding college match requirements.)

Local Match Requirements Have Changed Over Time

From 1987–88 through 2012–13, the Matriculation Program required community colleges to contribute some local funding as a match to state funding. The Student Success and Support Program (SSSP) continues this local match requirement. Though statute establishes the basic match requirement, regulations adopted by the California Community Colleges Board of Governors (BOG) sets the specific local match amount. In recent years, the BOG has amended regulations to lower the local match amount. These adjustments have been in response to large SSSP state funding increases, together with growing concerns about colleges’ ability to make their local match. The figure shows the local match amount from 1987–88 through 2016–17.

|

Year(s) |

Local Funds Per $1 of State Funds |

|

1987–88 to 2012–13 |

$3 |

|

2013–14 |

3 |

|

2014–15 |

2 |

|

2015–16 |

1 |

|

2016–17 |

1 |

SEP Requirement Restored and Funded. In 1991, the Legislature stated its statutory intent that public higher education in California provide equitable environments for students, regardless of their race/ethnicity, gender, age, disability, or economic circumstance. In 1992, the BOG approved associated regulations requiring colleges to create SEPs. Four years later, the BOG made college adoption of these plans a minimum requirement for state aid. The state did not provide dedicated funding for equity planning, however, and the planning requirement, in turn, was not enforced. In the 2014–15 Budget Act, the Legislature provided funding for the first time and the requirement to develop SEPs was reinstated. (See the nearby box regarding earmarked student equity funds for foster youth services.)

2014 Legislation Authorizes Supplemental Services for Foster Youth

Chapter 771 of 2014 (SB 1023, Liu) authorized the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office to fund specialized foster youth services in some community college districts. Beginning in 2015–16, the state budget has earmarked $15 million of the student equity appropriation for this purpose. The new program, called the Cooperating Agencies Foster Youth Educational Support (CAFYES) Program, is meant to encourage the enrollment and academic success of current and former foster youth in the community colleges. The program’s services, specified in the legislation, include outreach and recruitment, service coordination, counseling, book and supply grants, tutoring, independent living and financial literacy skills support, frequent in–person contact, career guidance, transfer counseling, child care and transportation assistance, and referrals to health services, mental health services, housing assistance, and other related services. Through a competitive grant process, the Chancellor’s Office awarded the CAFYES funds in January 2016 to ten districts operating 26 colleges.

Plans Must Identify Equity Gaps, Include Strategies to Close Them. Regulations specify that SEPs must be based on campus–level data in the areas of access, retention, degree and certificate completion, English as a Second Language (ESL) and basic skills completion, and transfer. Plans must identify any disparities in these outcomes among various groups of students. In addition, the plans must include goals to reduce equity gaps, strategies for attaining these goals, and sources of funds to support implementation.

Plans Use Three Methodologies to Identify Equity Gaps. To help colleges develop their plans, the Chancellor’s Office has provided three equity gap methodologies, described in Figure 2. All three approaches require colleges to disaggregate enrollment and outcomes data by race/ethnicity and gender, as well as for former foster youth, students with disabilities, low–income students, and veterans.

Figure 2

Equity Gap Methodologies

|

80 Percent Rule. Compares performance of either all students or the highest performing group, as the reference group, to performance of every other group. The performance of a group at less than 80 percent of the performance of the reference group is considered evidence of a gap. |

|

Proportionality. Compares a group’s percentage in an initial cohort (such as entering students) to its percentage of an outcome group (such as those completing a degree or certificate). A ratio of 1.0 indicates the group is represented in both initial and outcome groups at the same rate. A ratio of less than 1.0 indicates the initial cohort group is underrepresented in the outcome group. Each college determines a cut–off ratio for identifying a gap. |

|

Percentage Point Gap. Compares the percentage of a group that achieved an outcome with the percentage of all students achieving the same outcome. A group’s result that is at least 3 percentage points lower than all students is considered evidence of a gap. |

Colleges Receive Student Equity Funding Based on Student Enrollment and Community Risk Factors. Budget legislation in 2014–15 required the BOG to develop an allocation formula for student equity funds that provides more resources to districts with more “high–need” students. The legislation includes some criteria for calculating the number of high–need students in a district, such as the number of students receiving federal Pell Grants and the number of students from ZIP codes in the bottom two quintiles of college attainment, but the BOG also may use other criteria. The BOG–adopted student equity allocation formula distributes 40 percent of funds based on overall student enrollment, 25 percent on the number of students receiving a Pell Grant, and the remaining 35 percent on characteristics of the surrounding community, including its rates of poverty and educational attainment.

State Has Increased Ongoing Funding for Student Success Programs Significantly in Recent Years. As Figure 3 shows, the state increased annual funding for various CCC student success programs from $243 million in 2012–13 to $820 million in 2016–17—an increase of $577 million. The bulk of new spending ($391 million) has been for SSSP and student equity. Other smaller funding increases went to the following existing categorical programs: Extended Opportunity Programs and Services, Disabled Student Programs and Services, Basic Skills Initiative, California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) student services, and the Fund for Student Success. The state also funded a new professional development and technical assistance program for colleges—the Institutional Effectiveness Partnership Initiative. This initiative is to help improve administrative and educational operations and reduce accreditation sanctions and audit issues at colleges. New statewide technology projects (the Common Assessment Initiative, Education Planning Initiative, and electronic transcripts) also received funding.

Figure 3

State Funding for California Community Colleges’ Student Success Programs

(In Millions)

|

2012–13 Actual |

2013–14 Actual |

2014–15 Actual |

2015–16 Revised |

2016–17 Enacted |

Increase From 2012–13 |

|

|

Student Success and Support Program |

$49 |

$85 |

$185 |

$285 |

$285 |

$236 |

|

Student Equity Plans |

— |

— |

70 |

155 |

155 |

155 |

|

Extended Opportunity Programs and Services |

74 |

89 |

89 |

123 |

123 |

49 |

|

Disabled Student Program and Services |

69 |

84 |

114 |

115 |

115 |

46 |

|

Basic Skills Initiative |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20a |

50 |

30 |

|

CalWORKs Student Services |

27 |

35 |

35 |

35 |

44 |

17 |

|

Institutional Effectiveness |

— |

— |

3 |

18 |

28 |

28 |

|

Technology Projectsb |

— |

14 |

14 |

14 |

14 |

14 |

|

Fund for Student Successc |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

6 |

2 |

|

Totals |

$243 |

$331 |

$604 |

$769 |

$820 |

$577 |

|

aIn addition to the ongoing funding shown, the state provided $70 million in one–time funding—$60 million for the Community Colleges Basic Skills and Outcomes Transformation Program and $10 million for the Basic Skills Partnership Pilot Program. bConsists of the Common Assessment Initiative, Education Planning Initiative, and electronic transcripts. cSupports the Mathematics, Engineering, and Science Achievement program; Middle College High School program; and Puente Project. |

||||||

Findings

This section summarizes key actions the Chancellor’s Office has taken in administering CCC student success and equity programs. We then discuss how colleges have implemented these programs, with a particular focus on their spending, hiring, and provision of core services.

Systemwide Implementation

Chancellor’s Office Is Responsible for Statewide Implementation of SSSP and Student Equity. To direct college implementation efforts for each program, the Chancellor’s Office adopted planning and reporting requirements and templates. The templates specify what planning processes and content are required for each plan. For example, the SSSP template requires colleges to describe their planned activities for each core SSSP service. Similarly, the SEP template requires colleges to (1) set goals to reduce equity gaps for each of the specified student outcomes and (2) link specified activities to meeting those goals. The Chancellor’s Office also developed allocation formulas, expenditure guidelines, and audit processes for each program. Additionally, the Chancellor’s Office provides periodic feedback to colleges on how to improve their SSSP plans and SEPs, and it sponsors conferences and other professional development opportunities for college personnel to learn and share best practices.

Chancellor’s Office Initially Developed Three–Year Transition Plan to New SSSP Allocation Method. The Chancellor’s Office set forth a new allocation formula in a 2014 SSSP handbook. Because of concerns about the accuracy of initial data reports from colleges, the handbook sets forth a gradual transition to the new formula, intended to limit redistribution of funding before data systems were fine–tuned. Under the transition plan, the Chancellor’s Office would calculate each college’s funding using the new formula, compare it to a specified percent of the college’s 2014–15 funding (which used the old enrollment–based formula), and provide the higher of the two amounts to the college. For 2015–16 and 2016–17—the first two years the new formula was to be implemented—colleges were guaranteed at least 80 percent and 50 percent, respectively, of their 2014–15 funding. The new formula would be fully implemented beginning in 2017–18, but, to prevent large year–over–year changes, colleges would receive at least 95 percent of their prior–year’s funding thereafter (absent state budget reductions).

Chancellor’s Office Modified 2015–16 SSSP Funding Allocation. In practice, the Chancellor’s Office modified the 2015–16 guaranteed funding amount to account for a 54 percent increase in SSSP funding. With the adjustment, all colleges received an SSSP funding increase in 2015–16. About one–sixth of colleges received more funding because of the 80 percent guarantee than they would have received through the new formula. For 2016–17, the Chancellor’s Office has indicated that it intends to reduce the guarantee to 50 percent of 2015–16 funding. The Chancellor’s Office may reconsider, however, if this results in a large number of districts getting significantly less than they would under the old allocation method.

Chancellor’s Office Issued Expenditure Guidelines for SSSP and Student Equity. The guidelines identify eligible expenditures for each program. In general, expenditures must be consistent with the activities and goals in a college’s SSSP plan and SEP. For SSSP, allowable expenditures must relate to the core SSSP services. Expenditures may not include research unrelated to the delivery and evaluation of core services, salaries and benefits for staff who do not provide core services, and construction and/or rental of new space. The expenditure guidelines for student equity are more flexible than those for SSSP. Colleges may use student equity funds to provide a broad array of services as long as these expenditures target student groups with achievement gaps identified in a college’s SEP. Colleges also may use the funds for faculty and staff professional development, program administration, and coordination. The Chancellor’s Office conducts random audits of colleges to help ensure they accurately track core services and expenditures as well as use program funds only for allowable purposes.

Review Teams Score Plans and Provide Feedback. Small teams of Chancellor’s Office and college staff evaluate colleges’ SSSP plans and SEPs. Following training on an evaluation rubric, teams of three reviewers score plans and identify those that meet all requirements, meet minimum requirements but need improvement, or do not meet minimum requirements. The Chancellor’s Office provides colleges with their scores and feedback. It also has identified some exemplary plans for colleges to use as models. It posts these plans on its website.

Chancellor’s Office Hosts Conferences and Professional Development Opportunities. These opportunities include an annual SSSP All Directors’ Training and an annual Student Success Conference. Through these convenings, the Chancellor’s Office prepares new college administrators and staff to implement SSSP, provides colleges with new program guidance and updates on implementation efforts, and provides an opportunity for colleges to share effective practices. In addition, the Chancellor’s Office provides specialized workshops and online training opportunities through the Institutional Effectiveness Partnership Initiative and its Professional Learning Network.

Colleges Implemented Academic Standards for BOG Fee Waivers. Regulations require students to maintain a 2.0 grade point average (GPA) or above and complete more than 50 percent of their coursework to maintain eligibility for BOG fee waivers. Students who fail to meet these standards for two consecutive terms face potential loss of eligibility. Colleges were required to adopt local policies and processes for notifying students facing probation or loss of eligibility, informing all students of support services available to help them maintain or re–establish eligibility, and handling appeals of fee waiver decisions. Loss of eligibility initially took effect in fall 2016. The Chancellor’s Office reported that 94 percent of colleges responding to a June 2016 survey had notified affected students as required (with the remaining in progress) and all had adopted appeals processes for fee waiver decisions.

Chancellor’s Office Estimated Effects of Fee Waiver Standards on Students. Data on actual loss of fee waiver eligibility will not be available until after fall 2016 financial aid awards and appeals are completed. To estimate the effects of the new policies, however, Chancellor’s Office staff conducted a simulation using earlier student data and concluded that the projected number of students potentially losing eligibility for a BOG fee waiver was about 4 percent. The simulation also included breakdowns by racial/ethnic groups, gender, and categorical programs. Staff concluded that while some differential impacts were likely, they appeared to be small. The three racial/ethnic groups likely to be most affected, according to the simulation, were Hispanics, African–Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Those groups had projected loss rates of 4.8 percent, 4.5 percent, and 4.5 percent, respectively. According to the simulation’s projections, students with disabilities (6.1 percent), Extended Opportunity Programs and Services participants (4.5 percent), and male students (4.2 percent) were also more likely to lose eligibility.

SSSP Implementation

Our evaluation of colleges’ SSSP implementation included an analysis of Chancellor’s Office data and colleges’ 2014–15 year–end SSSP expenditure reports; a survey we conducted of colleges’ 2014–15 and 2015–16 SSSP hiring; a review of a sample of college SSSP plans; and interviews with academic, student services, and administrative personnel at a sample of colleges. Below, we present key findings from our SSSP evaluation.

Colleges Implemented Priority Registration Policies for Students. Under these policies, new students must identify a course of study and complete assessment and placement, orientation, and abbreviated education plans to receive priority course registration. Students with priority registration can sign up for courses earlier than other students, increasing the likelihood they will get the courses they want. Continuing students must complete comprehensive education plans after earning 15 degree–applicable units or before their third term, whichever comes first, to maintain registration priority. The regulations authorize colleges to go beyond priority registration and place a registration hold for students who have not completed the necessary steps. Students with a registration hold cannot sign up for courses until they meet certain conditions. We found that few colleges have opted to use registration holds.

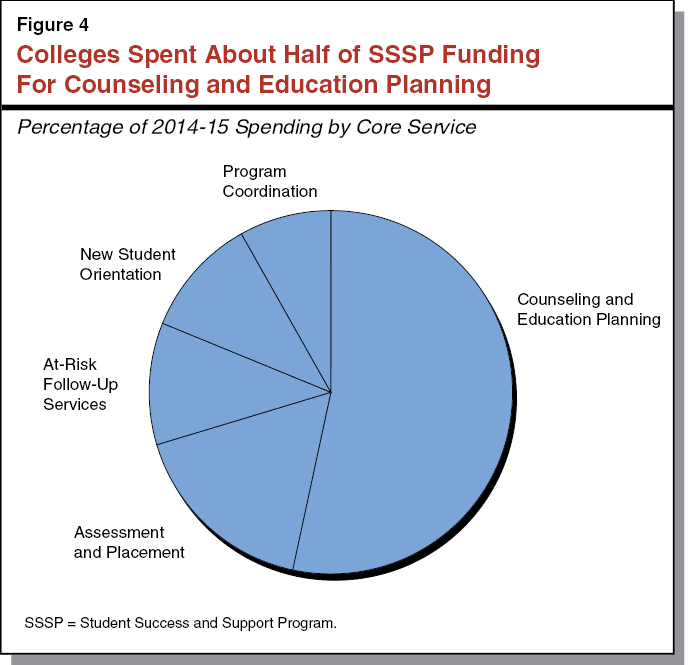

Colleges Reported Using a Majority of Their SSSP Funds for Counseling and Education Planning. Required expenditure reports classify expenses by core SSSP service as well as for program coordination, which refers to the coordination of services across departments as well as the development and implementation of SSSP budgets and plans. According to the 2014–15 year–end reports, colleges spent more than half of their SSSP allocations providing students with counseling and education planning services. (The reporting template combines these services.) Figure 4 shows reported SSSP spending by core service.

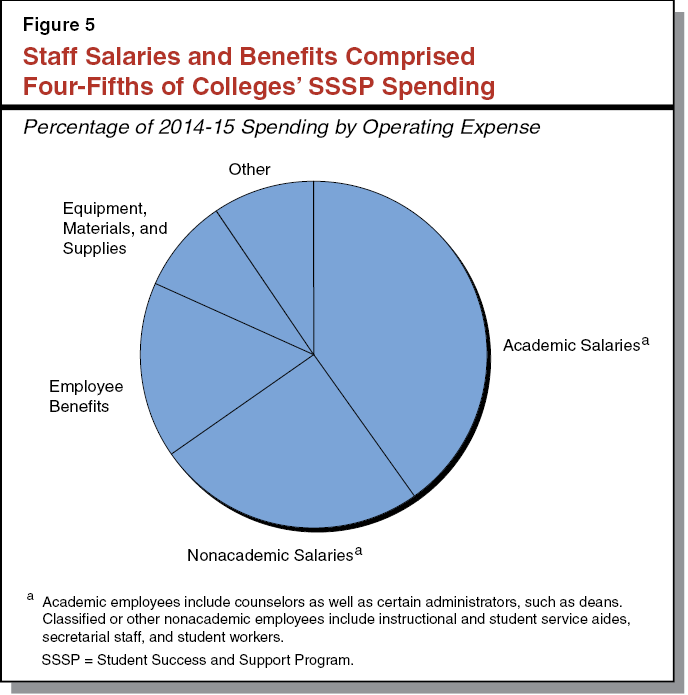

Colleges Reported Spending Most of Their SSSP Funds on Staff. The colleges’ expenditure reports also break down operating expenses into categories such as salaries, benefits, and equipment. According to the 2014–15 year–end reports, colleges spent 81 percent of their SSSP allocations on salaries and benefits, as shown in Figure 5.

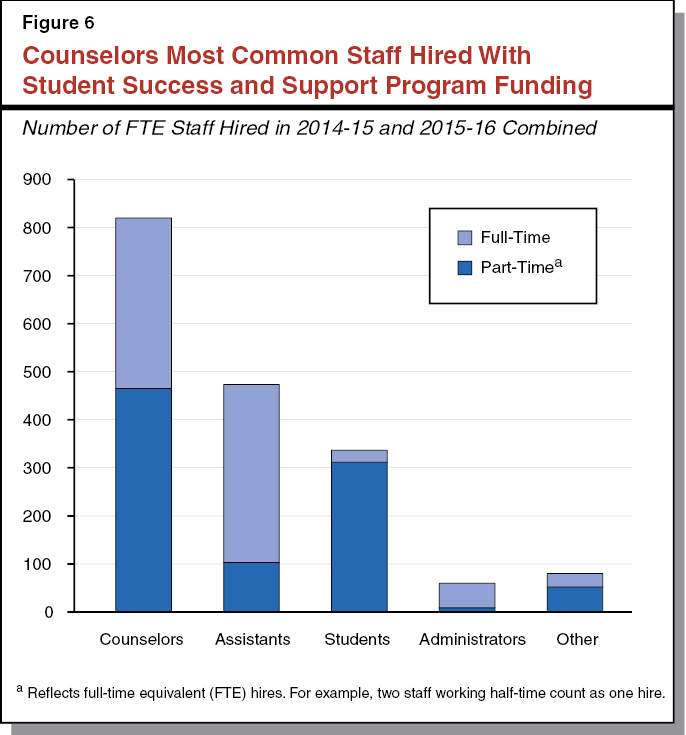

Funds Are Supporting Existing and New Staff. Colleges are using SSSP funds to support existing staff who provided services in the old Matriculation Program. In addition, as Figure 6 shows, colleges reported hiring about 1,800 new full–time equivalent (FTE) employees with SSSP funding in 2014–15 and 2015–16 combined. (For reference, one full–time employee or two half–time employees equal one FTE.) The new hires include 800 FTE counselors—44 percent of the total. Program assistants and student workers represented nearly all remaining new hires. Of the approximately three–quarters of CCC’s 113 colleges that responded to our survey, three–fourths reported hiring new staff with SSSP funds. Colleges, however, differed somewhat in the types of staff they hired. About one–third of colleges hired no new counselors, 39 percent hired no new assistants, and 59 percent hired no new student workers.

Full–Time Counselor Hires Increasing. Whereas 38 percent of new counselor FTEs hired in 2014–15 were full time, 48 percent of those hired in 2015–16 were full time. Colleges report needing as much as one year to complete the hiring process for a full–time, permanent counseling position. Accordingly, we expect colleges will reflect additional full–time counselor hiring related to the large 2015–16 SSSP augmentation in their 2016–17 reports.

Colleges Continuing to Hire Part–Time Counselors. While our staffing survey showed colleges are increasing their hiring of full–time counselors, a majority of colleges continued to hire primarily or exclusively part–time counselors. Some colleges indicated that part–time counselors help meet student demand for core SSSP services during peak times, such as the first few weeks of a term when most students plan and register for their classes. In addition, part–time counselors spend a greater share of their hours providing direct services to students than full–time counselors because they have fewer other responsibilities. Though colleges’ hiring decisions appear driven primarily by service considerations, colleges also acknowledged that past funding cuts to categorical programs during economic downturns account for some of their reluctance to hire more full–time staff using SSSP and student equity funds.

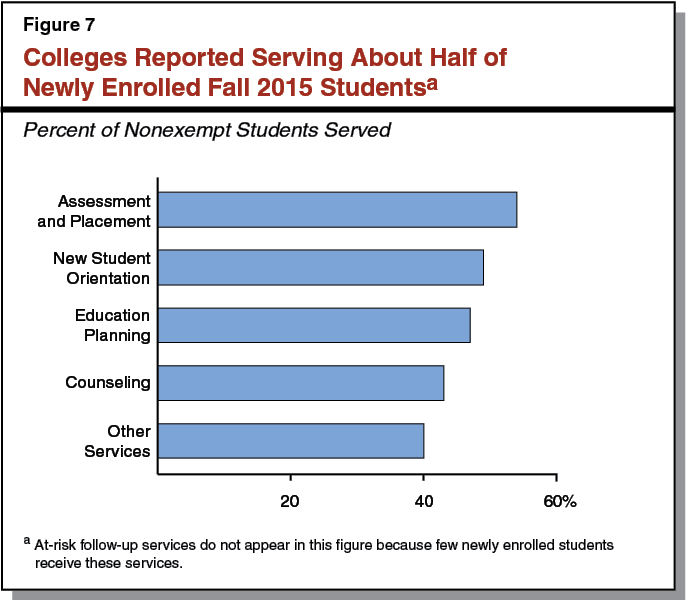

Colleges Reported Providing Core SSSP Services to Fewer Than Half of Newly Enrolled Fall 2014 Students. The most common services nonexempt students received were assessment and placement (44 percent of students) and new student orientation (37 percent of students). (Colleges began submitting core service data in the summer 2014 term. As a result, fall 2014 numbers exclude some core services that entering students may have received prior to their first course enrollment, such as assessment and orientation sessions that some colleges offer to prospective students during the spring term of their senior year in high school.)

By Fall 2015, Colleges Reported Serving a Higher Share of Newly Enrolled Students. Figure 7 shows the percentage of newly enrolled, nonexempt fall 2015 students who received each core service. (The numbers include services the students received in spring 2015, prior to their first course enrollment. As a result, the numbers are not directly comparable to fall 2014 information.) A majority of newly enrolled fall 2015 students had received assessment and placement services (54 percent of students) and a near majority had received orientation (49 percent of students) by the end of the fall term. Colleges also provided more counseling and education planning services to newly enrolled students. Nonetheless, the percentage of students receiving services remains low.

Examples of SSSP Activities. Implementation of the core SSSP services varied by college. Many colleges, however, added online orientation services. Many also expanded existing activities, such as small group sessions that provide new students with orientation, assessment and placement, and abbreviated education planning in a single visit. Some piloted new activities. For example, several colleges initiated intensive summer bridge experiences where a small cohort of basic skills students completes two full weeks of courses to accelerate English and math remediation. Figure 8 provides examples of common activities implemented or expanded under SSSP.

Figure 8

Common Student Success and Support Program (SSSP) Activities

|

Core SSSP Service |

Common Activities |

|

Assessment and Placement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

New Student Orientation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Education Planning |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Counseling |

|

|

|

|

At–Risk Follow–Up Services |

|

|

Student Equity Implementation

Similar to our evaluation of SSSP implementation, our student equity analysis included a review of colleges’ SEPs and expenditure reports, a staffing survey, and interviews with college personnel. We also interviewed equity experts who have helped colleges develop their SEPs. Below, we present our key findings.

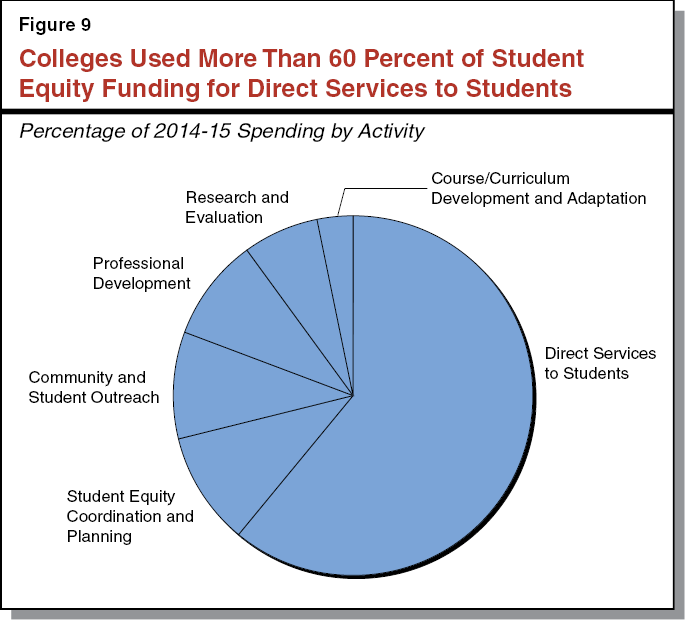

Colleges Reported Using More Than 60 Percent of Funds for Direct Services to Students. Colleges’ student equity year–end expenditure reports classify expenditures under eight student equity activities, ranging from direct student services (such as counseling, tutoring, categorical programs, and financial assistance) to program coordination and planning. Figure 9 shows 2014–15 expenditures in each of these eight categories. Colleges spent more than 60 percent of their student equity funds on direct services to students; 10 percent each on coordination, outreach, and professional development; and the remainder on research, evaluation, and curriculum development.

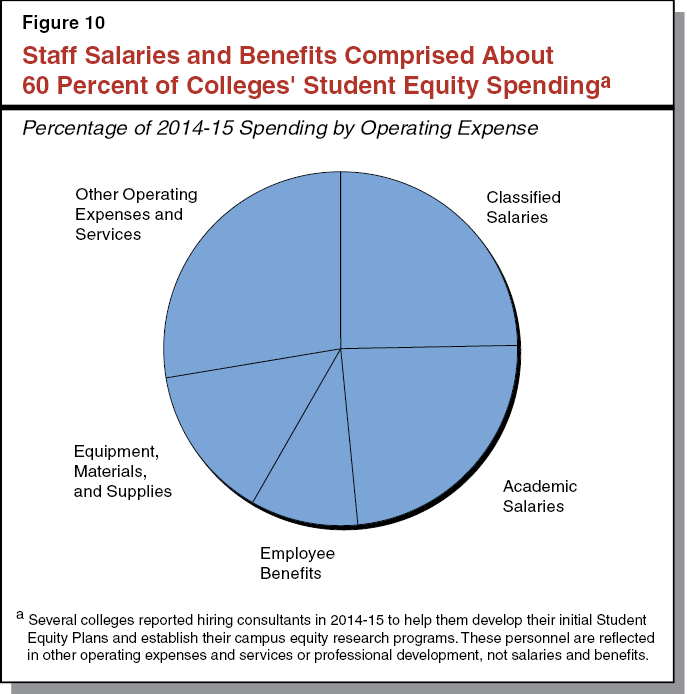

Colleges Reported Spending Nearly 60 Percent of Student Equity Funds on Staff. According to the 2014–15 reports, colleges spent 59 percent of their student equity allocations on salaries and benefits, as shown in Figure 10.

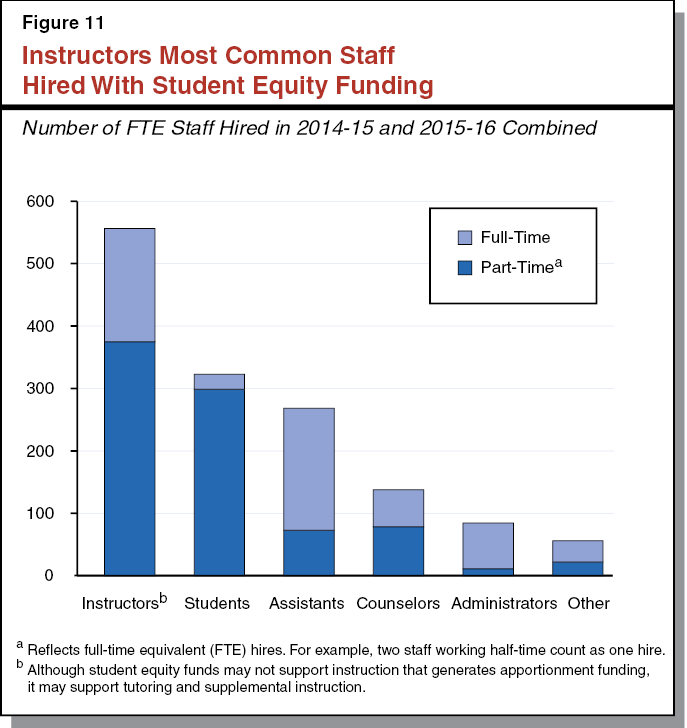

Funds Are Supporting New Instructors and Other Staff. As Figure 11 shows, colleges reported hiring about 1,400 FTE employees with student equity funding in 2014–15 and 2015–16 combined. The new hires include 550 FTE instructors (including tutors)—39 percent of the total. Student workers and program assistants represented most of the remaining new hires. Most colleges we surveyed (78 percent) reported hiring new staff with student equity funds. Some colleges reported hiring fewer staff in 2014–15 to give themselves more time to complete their SEPs and determine how best to use their funding. Several colleges cited gaps in their research on student disparities as another reason to postpone hiring. Others waited to decide how to administer the program, with some colleges combining their student equity and success programs under one administrator and others maintaining separate leadership.

Examples of Student Equity Activities. Figure 12 provides some examples of common student equity activities implemented in 2014–15 and 2015–16. Several colleges used student equity funding for expenditures such as targeted student support services, additional research and evaluation staff for equity–related projects, supplemental instruction for basic skills and ESL students, and equity–related professional development opportunities for administrators and faculty. Colleges differed, however, in how they addressed equity gaps of different student groups. Some colleges funded programs and services, such as math labs and writing workshops, shown to improve overall student achievement on their campuses. Other colleges funded programs and services for specific student groups, such as learning communities for underrepresented minorities and student services staff dedicated to serving veterans, disabled students, or other student groups.

Figure 12

Common Student Equity Activities

|

Outcome Indicator |

Common Activities |

|

Access |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Overall Course Completion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

English as a Second Language (ESL) and Basic Skills Completion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Degree and Certificate Completion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Transfer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other College or Districtwide Initiatives Affecting Several Indicators |

|

|

|

|

LAO Assessment of Implementation to Date

Based on our review, we find that systemwide and college efforts to implement SSSP and student equity generally are consistent with the intent of Chapter 624. Colleges are hiring more staff, providing more students with services, and working to reduce gaps in access and outcomes on their campuses. Though progress is moving in the right direction, it remains slow and uneven for several reasons we describe below. We first discuss our assessment of systemwide implementation of these programs, followed by our assessment of college implementation efforts. Figure 13 summarizes our assessment in these two areas.

Figure 13

Summary of Assessment

|

Systemwide Implementation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

College Implementation |

|

|

|

|

Systemwide Implementation

Granting Priority Registration Has Had Limited Effect. As mentioned earlier, few colleges have opted to place registration holds for students who have not completed orientation, assessment, and education planning. Most have relied instead on registration priority as an incentive for students to complete these services. The recovering economy, however, has limited the effectiveness of priority registration as an incentive in the past few years. Unlike during the recession, when students competed for access to a shrinking number of course sections, colleges now report that students generally can access desired classes regardless of whether they have priority enrollment. Although some courses still fill up, increased funding for enrollment growth and declining enrollment due to a recovering job market have eliminated much of the scarcity students previously experienced when registering for classes.

Current SSSP and Student Equity Planning and Reporting Processes Are Cumbersome. The Chancellor’s Office developed the templates and deadlines for SSSP plans and SEPs independently from each other. Perhaps as a result of this approach, the required information, formats, and due dates for the two programs are not aligned. In an attempt to coordinate their student success efforts, some colleges use detailed crosswalks outlining which types of services and expenditures each program can provide and when plans and reports are due. Some colleges also have tried to combine certain committees to help coordinate planning for the two programs, but other colleges have separate committees for each plan. Compounding the SSSP plan and SEP alignment problem, colleges have to complete or update annually at least a dozen other plans, including their strategic, educational master, facility master, basic skills, institutional effectiveness, and other categorical program plans, as well as a number of other operational and division plans, program reviews, and accreditation self–studies. Colleges must coordinate their student success and equity efforts with several of these other plans, yet the reporting requirements remain separate. Several colleges have hired additional management staff specifically to contend with the increasing number of reporting requirements.

Chancellor’s Office Working on Streamlining Planning and Reporting. Given the increase in reporting requirements, the Chancellor’s Office recently suspended the requirement to submit 2016–17 SSSP plans, SEPs, and Basic Skills Initiative plans while it explores combining these three plans into one. The Chancellor’s Office is trying to better align its requirements across all categorical programs and foster more integrated planning at campuses. These efforts are in their infancy, and much more work is needed to streamline planning and reporting for community college programs, including SSSP plans and SEPs.

Equity Gap Analysis Has Two Main Problems. First, the determination of whether an equity gap exists for a student group at a college is very sensitive to the gap analysis method and reference group the college selects. A majority–Hispanic college, for example, could deem that Hispanic students do not have a low completion rate if the college uses “all students” as the reference group—even if Hispanic students at the college complete at only half the rate of another student group. This is because the Hispanic students would have a large influence on the average for all students, and thus their completion rate would be close to the overall average. The second problem is that a group’s underrepresentation for an outcome does not necessarily indicate an equity gap for the group. The clearest example is for access, where colleges compare the demographics of their students to that of the surrounding community to identify equity gaps. Because nonwhite and financially disadvantaged students disproportionately attend community colleges, the gap analysis suggests that white and affluent students experience disproportionately low access to community colleges. A plausible alternative interpretation is that these students have equal access to community colleges but more options to attend other colleges. Some colleges used additional information, such as their knowledge of the community, to help interpret the results of equity gap calculations. Others, however, took the results at face value and developed strategies, such as increased outreach to white and affluent students, to address the identified equity gaps.

Chancellor’s Office Providing Adequate Oversight of SSSP and Student Equity Implementation. The Chancellor’s Office has made notable progress in the systemwide implementation of SSSP and student equity, especially with respect to clarifying program rules, refining administrative procedures, and offering professional development conferences to disseminate best practices. These activities have been well received by colleges, with conferences routinely filling to capacity. College and district efforts at implementation, however, are more difficult for the Chancellor’s Office to oversee. The office must rely on data review and retrospective audits to ensure accountability for program funds.

Reporting Lag Hampers Legislature’s Ability to Monitor Results. The CCC’s online Student Success Scorecard is one of the main ways the Legislature can monitor CCC student outcomes. The scorecard displays systemwide and college outcomes in eight key performance measures for a cohort of students (disaggregated by age, race/ethnicity, and gender). The benefit of the scorecard is limited, however, in that it reports outcomes for the cohort six years after initial enrollment. District and college personnel have indicated that they expect their SSSP efforts to begin improving student outcomes by 2017–18—just before our third report. Under existing reporting practices, data on affected students (those who first enrolled during 2014–15) will not be available until 2020–21—well after our third and fourth reports are due.

College Implementation

Provision of Core SSSP Services Moving in Right Direction. Although many newly enrolled students still are not receiving all core SSSP services, several colleges have shown significant progress in providing students with these services between fall 2014 and fall 2015, and we expect this trend to continue. The growing number of new counselors and other student support personnel being hired, along with continued development of alternative delivery methods such as online and group counseling sessions, should enable colleges to further increase the number of students receiving core services. Systemwide technology projects also will streamline service delivery for participating colleges.

Course Alignment With Student Education Plans Still Needs Work. Now that more students are completing education plans, colleges have an opportunity to better match course offerings with these plans. Yet, most colleges continue to schedule courses using past course enrollment data. In our 2014 report, we identified this as one of three key areas needing focused attention, but colleges have made little improvement in this area. (See the nearby box for an update on the other two areas, for which progress has been more substantial.) Despite the lack of progress systemwide, a few districts and colleges are taking steps toward better matching course offerings with student needs. One district we interviewed, for example, had analyzed course scheduling for the top degree programs its students identified in their education plans. Its analysis identified some poor sequencing of course offerings, such as not offering required prerequisites for a certain course in the term immediately prior to offering the course. The analysis also showed high–demand courses that had become bottlenecks on degree pathways, with few options for students to enroll outside of peak daytime hours. The district improved the sequence of course offerings and provided more sections of high–demand courses at various times to improve students’ ability to progress toward their goals. In addition, several colleges are creating highly structured two– and three–year course schedules based on the education goal a student identifies. These colleges guarantee availability of the necessary courses in the right sequence for cohorts of students in a program. These colleges are the exceptions, however, and much work remains to identify additional best practices and disseminate them across the system.

Notable Progress on Two Priorities Identified in Our 2014 Report

In addition to improving course alignment, our first progress report on implementation of Chapter 624 of 2012 (SB 1456, Lowenthal) identified two other key areas in need of improvement: (1) basic skills instruction and (2) professional development. As highlighted below, we found substantial progress in two of these areas since our last report.

Improving Basic Skills Instruction. Over the past two years, the state has taken notable actions to improve basic skills instruction. In the 2015–16 budget, the Legislature funded two competitive, one–time basic skills grant programs to transform how community colleges (in collaboration with public schools and universities) provide basic skills instruction. These programs emphasized the use of evidence–based strategies for improving basic skills outcomes, including using multiple measures for student assessment and placement, better aligning remedial and college–level curriculum, and integrating proactive student services with basic skills instruction. In the 2016–17 budget, the Legislature amended the longstanding Basic Skills Initiative program, adding the emphasis on evidence–based practices and increasing funding from $20 million to $50 million annually.

Providing Effective Professional Development. Over the past two years, the state also has taken notable actions to foster more effective professional development. Specifically, the Legislature provided $12 million in ongoing Proposition 98 funding in 2015–16 and an additional $8 million ongoing in 2016–17 to improve the statewide professional development system. As part of the enhanced system, the Chancellor’s Office is hosting a series of annual, regional training workshops and has created an online professional development portal (called the Professional Learning Network). Workshop topics in 2015–16 included student success research and practice, basic skills transformation grant planning, and enrollment management. In our interviews, participants consistently gave high marks to the workshops, describing them as timely, informative, and engaging.

Student Equity Spending Generally Complements Other Categorical Spending. Colleges, in general, used student equity funding for the intended purposes of identifying and attempting to reduce disparities among student groups. Many colleges, for example, funded staff to identify gaps, provide instructional support and student services to help reduce these gaps, and train faculty and staff on equity issues. At several colleges, equity spending complemented SSSP spending by providing more core SSSP services to groups with identified disparities in outcomes. One college, for example, created a number of separate resource centers where students from target groups could access core services as well as additional support services. At other colleges, equity spending provided services not supported by SSSP funds to all students. Some colleges, for example, expanded math and writing labs that are ineligible for SSSP funding but shown to improve success for all students. The greater flexibility in allowable student equity expenditures facilitated the braiding of student equity funds with SSSP funds.

Some Colleges Spending Funds More Strategically Than Others. Typically, we found the more strategic efforts at colleges that have strong leadership and already had been working on how to change their institutions to improve student success and equity. A number of these colleges had incorporated SSSP and student equity goals into their strategic plans, had achieved broad campus buy–in, and were able to deploy the new resources relatively quickly. They planned for the long–term implementation of SSSP and student equity by methodically evaluating their existing programs and services, discontinuing ineffective activities, proposing new ones based on research and best practices, and hiring new staff. In contrast, colleges that were not already engaged in student success and equity efforts had a much longer lead time to develop and approve plans through their shared governance structures and deploy their funds. Large augmentations to the programs starting in 2013–14—and limited time for colleges to plan and spend new funds—led some of these colleges to delay hiring and primarily fund existing programs and services without evaluating their effectiveness. Other colleges spread funding across dozens of activities rather than focusing on a smaller number of targeted, evidence–based practices.

Recommendations

Below, we make five recommendations on how to improve the implementation and evaluation of SSSP and student equity.

Require Students to Complete Assessment, Orientation, and Education Planning. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature direct the BOG to strengthen the requirement that students complete these services, including potentially requiring that colleges with low SSSP participation rates employ registration holds to ensure that more students receive needed services. (We recommend the BOG continue to exempt certain students, such as those who already have degrees, from completing these services.) In tandem with stronger registration policies, the BOG could require colleges to mitigate any disproportionate impact on groups of students. The BOG, for example, could direct colleges to use student equity funds to help affected groups access SSSP services, as well as ensure that colleges have adequate appeal processes.

Require Chancellor’s Office to Standardize Equity Gap Methodology for Each Measured Outcome. We recommend the Legislature direct the Chancellor’s Office, prior to the next required SEP submission, to identify a consistent way of measuring disparities for each of the specified student outcomes. Specifically, for each student outcome (such as course completion), we recommend the Chancellor’s Office select one methodology—either from the three currently used or an alternative approach—and establish any corresponding rules for using the methodology (such as for defining the reference group). The Chancellor’s Office could then set cut points for identifying disparities. For example, were the Chancellor’s Office to choose the 80 percent rule for course completion, it could direct colleges to use the highest performing group as the reference group. If it were to use the proportionality method, it could set 0.90 as the cutoff for identifying a disparity. In addition to this standardization, we recommend the Legislature direct the Chancellor’s Office to provide related training for campus personnel on analyzing disparities.

Require Chancellor’s Office to Produce a Special Three–Year Student Success Scorecard. As noted earlier, the current Student Success Scorecard does not measure performance for a cohort of students until six years after initial enrollment. This means data on students who enrolled after SSSP and student equity implementation will not be available until 2020–21. To permit the Legislature to evaluate these programs before 2020–21, we recommend, as an interim measure, the Chancellor’s Office produce a three–year scorecard. This three–year scorecard would contain the same performance measures as the existing six–year scorecard, disaggregated by whether students received each of the core SSSP services. We recommend the Chancellor’s Office release the three–year scorecard by October 2017 and include data for the cohort entering in 2014–15, as well as the cohorts entering in 2012–13 and 2013–14 for comparison.

Require Chancellor’s Office to Promote Evidence–Based Practices in SSSP and Student Equity. We recommend the Legislature direct the Chancellor’s Office to compile a list of evidence–based practices for SSSP and student equity and make it available publicly no later than October 1, 2018. Over time, the state could further direct the use of SSSP and student equity funds toward best practices as it has done for basic skills. Over the past few years, a body of research similar to that for basic skills instruction has been developing on matriculation services, other student success interventions, and closing equity gaps. Colleges also are gaining experience implementing administrative provisions of Chapter 624, such as academic progress notification and appeals, and have developed some effective strategies in these areas. While the consensus around effective practices for SSSP and student equity is not yet as clear as for basic skills, sufficient research and evaluation exists to begin focusing colleges on strategies that have been effective at CCC campuses and other community colleges nationally. In addition to using the results of academic research on effective practices and consulting with experts, the Chancellor’s Office could identify practices employed at CCC campuses that have made the greatest gains in student outcomes. The Chancellor’s Office could encourage colleges to use the identified practices in their SSSP and student equity programs and require them to justify the use of other strategies that have not been shown to be effective.

Require Chancellor’s Office to Collect Data on Course Alignment With Education Plans. To date, the Legislature does not have a way to monitor (1) the extent to which colleges’ course offerings align with students’ education needs as identified in their education plans, or (2) the extent to which students are following their education plans. To address these gaps, the Legislature could direct the Chancellor’s Office to identify, by January 1, 2018, strategies for monitoring and improving the alignment of course offerings and education plans. To conduct the initial data collection and analysis, the Chancellor’s Office could focus on pilot colleges for the Education Planning Initiative, which already have implemented electronic education plans.

Conclusion

Over the past few years, the Legislature has increased funding significantly for CCC student success and equity programs. Colleges generally are implementing these programs consistent with the intent of Chapter 624. They have hired additional counselors and other student support staff, provided more matriculation and support services to students, and increased their focus on student equity. To improve the implementation and evaluation of SSSP and student equity moving forward, we recommend strengthening the requirement for students to complete core SSSP services, choosing a consistent approach for measuring equity gaps, requiring a special three–year Student Success Scorecard, identifying and disseminating effective practices, and improving the alignment of course offerings with student education plans. Taken together, we think these recommendations will promote continued progress on student success and equity.