LAO Report

June 22, 2015 Review of Recent Changes to

The Cal Grant C Program

Executive Summary

Report Reviews Effects of Recent Changes to Cal Grant C Program. The Cal Grant C program provides financial aid to support California students pursuing occupational and technical training. With Chapter 627, Statutes of 2011 (SB 451, Price), and later with Chapter 692, Statutes of 2014 (SB 1028, Jackson), the Legislature modified the eligibility criteria for the Cal Grant C program. Specifically, the legislation prioritizes grants for applicants pursuing training in occupations that meet strategic workforce needs and those coming from disadvantaged backgrounds. To ensure these changes are having the intended effects, the Legislature requested that our office prepare a report on the implementation of the new rules and their impacts on Cal Grant C recipients, including (1) recipients’ demographic information, (2) which occupations were prioritized for grant applicants, (3) the number of applicants who received priority status, and (4) recipients’ employment outcomes. To track longer–term outcomes, legislation directs our office to prepare a similar report every two years.

Prioritization Criteria Instituted, But Have Had Limited Effect on Cal Grant C Applicants Thus Far. Pursuant to Chapter 627, the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC) developed a list of training programs for occupations associated with high wages, growth, or employer need, for which Cal Grant C applicants would receive priority status. The list of 13 prioritized occupations includes several in the health care field, such as registered and licensed vocational nursing. (The commission will further refine this list in 2016 when it incorporates additional criteria pursuant to Chapter 692.) CSAC indicates that for the 2012–13 grant cohort, around 1,500 students qualified to receive a Cal Grant C offer because of the extra “priority points” they received for expressing intent to pursue one of these prioritized occupations. In 2013–14 and 2014–15, however, indicating intent to pursue one of the prioritized occupations did not advantage certain Cal Grant C applicants over others. This is because a drop in the number of Cal Grant C applicants, combined with an increase in the number of grants CSAC offered, resulted in essentially all applicants receiving grant offers in those years.

Premature to Assess Prioritization Criteria’s Effect on Participant Outcomes, Recommend Waiting for More Data Before Making Further Refinements. Because employment data tend to lag several years, we are not yet able to assess whether the prioritization criteria have had any effect on the types of jobs attained by Cal Grant C recipients. Moreover, while data show recent cohorts of Cal Grant C recipients were more likely to pursue certificates or degrees in program areas related to CSAC’s prioritized occupations, whether this trend is due to the prioritization criteria—or rather a reflection of the underlying job market—still is unclear. Given these uncertainties, and the fact that CSAC has yet to fully implement the changes included in Chapter 692, we recommend the Legislature hold off on making additional refinements to Cal Grant C prioritization criteria until more data are available on the effects of the recent modifications.

Completing Course of Study is Important Indicator for Successful Employment, Recommend Legislature Focus Future Efforts on Improving Completion Rates. We believe next steps in targeting the Cal Grant C program towards meeting state workforce needs should focus on helping grantees complete their training programs. Available data show that Cal Grant C recipients who complete a certificate or degree program are more likely to be employed and working in higher–skilled employment sectors than those who do not complete their training programs. Yet available data also show that only half of Cal Grant C recipients complete their courses of study. Moreover, typically recipients ultimately complete their programs only if they do so relatively quickly (within three years). To improve these completion rates, we recommend the Legislature ensure that statewide initiatives to improve student outcomes include adequate focus on students enrolling in career technical programs. A forthcoming report from a community college task force on workforce preparation could provide helpful ideas for future reforms.

If Legislature Wants to Increase Grant Amounts for CCC Students, Recommend Making Change Through the Budget. One change contained in Chapter 692 may not be having its intended effect. Cal Grant C is allocated in two separate amounts—$2,462 per student annually for tuition and fees, and $547 for books and supplies—but because of fee waivers, students attending community colleges are only eligible to receive the smaller grant for books and supplies. Chapter 692 included language that expanded the allowable uses of Cal Grant C to include living expenses. According to representatives from the author’s office and certain stakeholders who were involved in developing the legislation, this was intended to increase the amount of Cal Grant C aid that CCC students could receive. Yet because that effect was not clearly stated in the legislation, highlighted in legislative analyses of the bill, or included in the budget act, CSAC and the Department of Finance do not share this interpretation of the language, and have not altered grant amounts. Should the Legislature wish to increase grant amounts for CCC students, we recommend making this change in the budget act provisional language that specifies the amounts and uses for Cal Grants. (If the Legislature opts to increase individual grant amounts, it also will need to determine whether it wants to maintain existing spending levels and provide grants to fewer students, or increase overall spending for Cal Grant C in order to provide the larger grants to the same number of students.)

Recommend Shifting Ongoing Cal Grant C Reporting Requirements to CSAC. After we provide a companion to this report in 2017, we recommend the Legislature shift responsibility to CSAC for any subsequent Cal Grant C updates it requires. Statute currently requires that we report to the Legislature on Cal Grant C every two years. Absent future policy changes, however, we do not believe future reports—beyond an updated review two years from now—will necessitate a comparable level of legislative analysis from our office. We believe CSAC is well–positioned to provide any summary data the Legislature requires on Cal Grant C in the future.

Introduction

The Cal Grant C program provides financial aid to support California students pursuing occupational and technical training. With Chapter 627, Statutes of 2011 (SB 451, Price), and later with Chapter 692, Statutes of 2014 (SB 1028, Jackson), the Legislature modified the eligibility criteria for the Cal Grant C program. Specifically, the legislation prioritizes Cal Grant C applicants pursuing training in occupations that meet strategic workforce needs and those coming from disadvantaged backgrounds. To ensure these changes are having the intended effects, the Legislature requested that our office prepare a report on the implementation of the new rules and their impacts on Cal Grant C recipients, including (1) recipients’ demographic information, (2) which occupations were prioritized for grant applicants, (3) the number of applicants who received priority status, and (4) recipients’ employment outcomes. To track longer–term outcomes, legislation directs our office to prepare a similar report every two years.

While several of the Cal Grant C changes were enacted too recently to yet allow for a conclusive analysis of their impacts, this report summarizes available data and highlights emerging issues. We begin by providing some background on the Cal Grant C program and recent legislative changes. We then describe our key findings, including a detailed summary of the new rules, initial indications of how the changes might be affecting Cal Grant C recipients, and trends revealed by earlier cohorts of grant recipients. Finally, we recommend how the Legislature might make additional improvements to Cal Grant C.

Background

Cal Grants

Cal Grant Is State’s Primary Student Aid Program. Cal Grants provide financial aid awards to financially needy students who meet academic and other eligibility requirements. There are three types of Cal Grants: Cal Grant A (with higher academic requirements), Cal Grant B (with a lower income eligibility ceiling), and Cal Grant C (for vocational training). In 2014–15, the state spent $1.9 billion to award nearly 325,000 Cal Grants. These awards are administered by the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC), which has the authority to grant awards based on the criteria listed in the relevant sections of the state Education Code, as well as other criteria deemed appropriate by CSAC.

Cal Grant C Is Targeted for Technical and Vocational Education. Cal Grant C provides financial aid to students pursuing a vocational program at California Community Colleges (CCC), private colleges, or career technical schools. In 2014–15, the state spent an estimated $10 million for about 6,000 new Cal Grant C awards and nearly 3,500 renewal awards. (The cap on the number of new annual awards is specified in statute at 7,761 and has not changed since 2000–01. As discussed below, CSAC typically offers more but pays fewer than the cap because around 40 percent of awardees ultimately do not claim their grants.) Annual Cal Grant C awards are worth up to $2,462 for tuition and $547 for books and supplies, and may provide support for up to two years. Students attending CCC programs are only eligible to receive the smaller stipend for books, not the tuition grant, whereas students attending other schools receive a combined grant. (This is because CCC students who receive Cal Grant C also qualify for CCC Board of Governors’ fee waivers.) The CCC system is the primary destination of Cal Grant C recipients, typically serving between 60 percent and 70 percent of all grantees. (As discussed later, grantees’ enrollment patterns have fluctuated somewhat in recent years based on changes to eligibility standards for private colleges.)

Recent Legislative Changes to Cal Grant C

Policymakers Concerned About Cal Grant C Connection to Workforce Needs. The Cal Grant C program was conceived as a way to support the needs of the statewide workforce by aiding students who wish to enter a given profession in acquiring the necessary training, education, or certification. The original legislation, however, was silent on how best to align Cal Grant C–eligible training programs with statewide workforce needs. This led the Legislature to reexamine the grant program with an eye towards better aligning Cal Grant C with strategic and emerging workforce needs.

Legislature Enacted New Rules for Cal Grant C. With these objectives in mind, the Legislature enacted Chapter 627 in 2011 and Chapter 692 in 2014 to bring Cal Grant C in line with state workforce needs. These changes focused primarily on two areas: prioritizing students attending programs that meet strategic workforce needs, and focusing the program on economically disadvantaged and long–term unemployed applicants. (The Appendix displays the Cal Grant C statute incorporating the changes in Chapters 627 and 692.)

New Prioritization Rules for Eligible Programs. Chapter 627 required CSAC to prioritize the granting of Cal Grant C awards to students pursuing technical or vocational training in areas that meet at least two of the criteria shown in Figure 1. (No such prioritization criteria previously existed in legislation.) The bill required that CSAC consult with the state’s Employment Development Department (EDD) to determine which areas of training meet these criteria. The legislation also required that, beginning in 2014–15, CSAC prioritize applicants enrolling in programs that rate high in graduation rates and job placement data. The commission, however, must update its data system before it can collect the information necessary to implement this requirement, which is expected to take several years.

Figure 1

Legislation Prioritizes Cal Grant C for Applicants Pursuing Occupations That Meet Certain Criteria

|

Chapter 627a Criteria |

Chapter 692b Criteria |

|

High employer need |

High employer need or demand |

|

High employment growth |

High employment growth |

|

High salary or wage projections |

High salary and wage projections |

|

Part of a well–articulated career pathway to a job providing economic security |

|

|

aChapter 627, Statutes of 2011 (SB 451, Price). Occupation must meet at least two criteria to be prioritized. bChapter 692, Statutes of 2014 (SB 1028, Jackson). Occupation must meet at least two criteria to be prioritized. At least one must be high salary or part of a career pathway. |

|

Prioritization Rules to Be Further Modified Beginning 2016. Chapter 692 made additional changes to the prioritization criteria established by Chapter 627. As shown in Figure 1, the legislation added a new criterion and made slight modifications to two of the previous criteria. Additionally, Chapter 692 specified that to receive priority consideration, not only must an applicant be pursuing an occupation that meets at least two of the criteria, at least one of those must be from the latter two listed (associated with a high salary or part of a career pathway leading to economic security). The commission, however, will not implement these changes until it next revises its occupation priority areas, which the legislation requires be done by January 1, 2016 (affecting the 2016–17 grant cohort). In modifying these areas, the bill requires that CSAC consult with EDD, CCC, and the California Workforce Investment Board.

Additional Prioritization Criteria Will Focus on Economically Disadvantaged Applicants. Chapter 692 also broadened the criteria that CSAC may use to select applicants to receive Cal Grant C awards. Specifically, it directs CSAC to take the economic situation of applicants into account and give special consideration to students facing economic hardship or hurdles to employment, or who are long–term unemployed (defined as being unemployed for at least 26 weeks). These changes, which will take effect beginning with the 2015–16 grant cohort, are intended to address the fact that California has one of the highest long–term unemployment rates in the nation.

Expanded Definition of How Grant Can Be Used. In addition to modifying prioritization criteria, Chapter 692 made a change to the statute that articulates how students may use Cal Grant C awards. Besides tuition, fees, training–related supplies, and books, students now may use the grants to help cover living expenses. (As described later, various parties have differing interpretations regarding the intended effects of this change.)

Findings

In this section, we describe our key findings regarding the Cal Grant C program. First, we describe how recent changes in eligibility standards for colleges that participate in Cal Grant programs—unrelated to Chapters 627 and 692—have affected the number of Cal Grant C applicants and offers. Next, we explain how CSAC implemented the changes required by Chapter 627, and provide some initial analysis of resulting effects based on the limited outcome data that are available for recent cohorts of grant recipients. We also highlight how a recent change made by Chapter 692 may not be having its intended effect. Based on more robust outcome data available from earlier cohorts of Cal Grant C recipients, we conclude by discussing general trends that could inform future policy decisions.

Changes to Program Eligibility Standards Have Affected Cal Grant C Students

Changes Modified Which Programs Cal Grant C Recipients Can Attend. Figure 2 shows which types of schools Cal Grant C recipients attended from 2010–11 to 2014–15. As shown, the share of students attending CCC is notably higher in some years. This likely is due in part to new eligibility standards for colleges participating in Cal Grant programs that the Legislature adopted in 2011–12 and 2012–13. These changes rendered colleges with low graduation rates or high rates of students defaulting on federal loans ineligible to participate. (For more information on Cal Grant eligibility changes, see our 2013 report, An Analysis of New Cal Grant Eligibility Rules.) The new standards disqualified most private for–profit colleges in the state in 2012–13, including several Heald College campuses that historically have been popular destinations for Cal Grant C recipients. (No public colleges or universities were disqualified.) Several Heald campuses regained eligibility in 2013–14 and 2014–15, resulting in the notable resumption of Cal Grant C recipients attending private career colleges in these years. Subsequent to making the 2014–15 grant awards, however, CSAC again revoked eligibility for ten Heald campuses (as described in the nearby box), attended by 29 percent of the Cal Grant C recipients displayed in the figure for that year. As such, enrollment patterns in future years likely will revert to even larger shares of Cal Grant C recipients attending community colleges.

Figure 2

Recent Eligibility Changes Have Affected Cal Grant C Recipient Enrollment Patterns

Distribution of Recipients by Segmenta

|

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

|

|

California Community College |

53% |

58% |

88% |

78% |

58% |

|

Private career college |

45 |

39 |

10 |

21 |

40 |

|

Independent college or university |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

a Not displayed in the figure are about 0.5 percent of Cal Grant C recipients who attended a public college or university other than a community college. |

|||||

Cal Grant C Students Affected by Heald College Closure in 2015

Unexpected Closure of Heald College. In late April 2015, Corinthian Colleges, the parent company for Heald College, announced that all of its campus locations would immediately close. This move followed several months of federal and state sanctions resulting from evidence that the colleges had dramatically misrepresented job placement rates for their graduates. The immediate closure meant that currently enrolled students, including more than 1,000 Cal Grant C recipients attending Corinthian’s ten Heald campuses, could not complete their degree and certificate programs.

Cal Grant C Awards Are Portable . . . Cal Grant C recipients may use their awards at any eligible institution, including all 112 community colleges and dozens of private for–profit and nonprofit trade schools. Upon Heald’s closure announcement, the U.S. Department of Education, the California Community College system, and other organizations began working with Corinthian Colleges to help Heald College students in California find other institutions with similar educational programs into which they could transfer.

. . . But Students Face Challenges in Completing Programs. Although other Cal Grant–eligible institutions offer programs similar to those at Heald College, students seeking to transfer to other institutions face four major hurdles. First, some programs already have more applicants than available slots. As a result, students will have to compete for admission or register on waiting lists for programs. Second, each college campus determines to what extent it will award transfer credit for courses that students completed at Heald College. Most students likely will not receive full credit for their completed course work, and some will have to complete substantial additional work at their new colleges. Third, if students do transfer credits they earned at Heald, they also may carry forth all of the federal student loan debt they incurred. (Students who were unable to complete their courses of study at Heald typically are eligible for a full discharge of their federal student loans only if they do not transfer credits to continue their programs at another school.) Fourth, to the extent recipients have used some of their grant eligibility at Heald College, they will have less than two years remaining in their Cal Grant C awards. Consequently, some students—especially those transferring to private institutions—may find it difficult to pay for their educational programs. (At the time this report was published, the Legislature was considering legislation that would extend the Cal Grant eligibility period for former Heald students.)

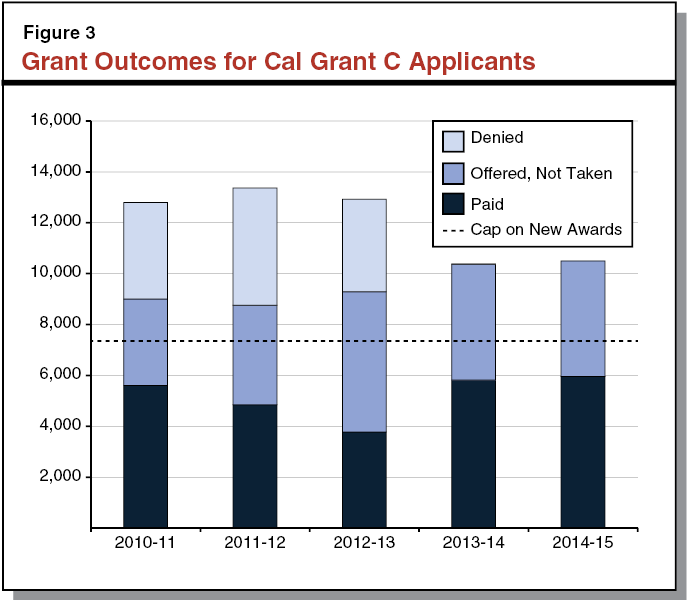

Changes Have Led to All Cal Grant C Applicants Being Offered Grants. Figure 3 displays the number and award status of Cal Grant C applicants over the past five years. Two factors combined such that essentially all Cal Grant C applicants were offered grants in 2013–14 and 2014–15. First, the number of students applying for grants declined notably between 2010–11 and 2014–15 (18 percent). This likely is related to the disqualification of many of the private for–profit colleges that students historically have preferred, such as Heald College. That is, many Cal Grant C–eligible students likely still opted to attend those schools and therefore were not eligible for the financial aid. Second, the total number of awards that CSAC offered each year increased notably across the five years (17 percent). This reflects the commission’s decision to expand the number of offers, given that many awardees ultimately opt not to accept the grants. (As shown in the figure, offering more grants has increased the number of grants paid out in recent years.)

CSAC Identified Prioritized Occupations

CSAC Created a Priority List of Programs Based on Statutory Criteria. As described above, Chapter 627 directed CSAC to develop a list of occupational or technical training areas for which Cal Grant C applicants would receive priority status. Figure 4 describes how CSAC defined which Cal Grant C–eligible occupations represent jobs that have high wages, growth, or need—the three prioritization criteria established in the legislation. Figure 5 displays the 13 occupations CSAC selected to prioritize based on these criteria. As shown in the figure, all of the selected occupations met at least two of these criteria (typically growth and need), and three occupations (registered nurses, police and sheriff patrol officers, and firefighters) met all three. As noted earlier, the list of prioritized occupations likely will change notably when CSAC incorporates the Chapter 692 requirements that focus on jobs with high salaries or established career pathways.

Figure 4

CSAC Definitions of Cal Grant C Prioritization Criteria

|

|

|

|

CSAC = California Student Aid Commission. |

Figure 5

Occupations for Which Cal Grant C Applicants Receive Priority Consideration

Shaded Cell Indicates Job Meets Criteria for High Wage, Growth, or Need

|

Occupation |

Median Income (Wage) |

Number Projected |

|

|

Jobs Created (Growth) |

Job Openings (Need) |

||

|

Registered nurses |

$83,653 |

60,800 |

10,210 |

|

Police and sheriff’s patrol officers |

79,450 |

5,200 |

2,380 |

|

Computer specialists |

78,765 |

5,000 |

1,220 |

|

Fire fighters |

66,256 |

5,700 |

1,630 |

|

Paralegals and legal assistants |

57,737 |

5,500 |

870 |

|

Carpenters |

52,383 |

10,200 |

2,750 |

|

Computer support specialists |

50,214 |

7,400 |

2,520 |

|

Licensed practical and vocational nurses |

49,818 |

13,600 |

3,340 |

|

Auto technicians and mechanics |

39,418 |

5,300 |

1,980 |

|

Fitness trainers and aerobics instructors |

39,166 |

8,700 |

1,450 |

|

Medical secretaries |

31,594 |

21,100 |

3,300 |

|

Preschool teachers |

28,883 |

6,600 |

1,770 |

|

Restaurant cooks |

24,337 |

14,200 |

3,990 |

Policy Does Not Ensure Grantees Ultimately Pursue Prioritized Occupations. There is no requirement that applicants who are prioritized for Cal Grant C based on the occupations they indicate on their applications ultimately pursue those same occupations. Beyond ensuring that it is a Cal Grant C–eligible course, neither CSAC nor the enrolling institutions follow up to confirm the types of programs in which grantees ultimately enroll. Representatives from both CSAC and CCC indicate such follow–up would be costly.

Prioritization Criteria Have Had Limited Effect on Applicants Thus Far

No Need for Prioritization in Recent Years. Figure 6 shows the number and proportion of individuals offered a Cal Grant C award who indicated intent to pursue one of the prioritized occupations over the past three years. As shown, the proportions drop off in the most recent two years, to around one–third of successful applicants (compared to more than half in 2012–13). This likely reflects the fact that, as discussed, all applicants were offered grants in 2013–14 and 2014–15. As such, indicating intent to pursue one of the prioritized occupations in these years did not advantage certain Cal Grant C applicants over others or skew the recipient pool toward those occupations. The prioritization criteria did have some effect in the first year they were implemented, however. CSAC indicates that for the 2012‑13 grant cohort, around 1,500 students qualified to receive a grant offer because of the extra “priority points” they received for expressing intent to pursue a prioritized occupation.

Figure 6

Students Who Indicated Priority Occupations

Of Students Offered Grantsa

|

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

|

|

Number |

5,240 |

3,772 |

3,669 |

|

Percent |

56% |

36% |

35% |

|

aData includes all applicants who were offered grants, whether or not they ultimately took them. |

|||

Recipient Pool Largely the Same as Before Prioritization Rule Changes. Implementing the prioritization criteria does not appear to have had a large effect on the age, gender, or employment status of Cal Grant C recipients, as shown in Figure 7. While there has been a slight shift to recipients under the age of 25 (34 percent in 2014–15 compared to 25 percent in 2010–11), demographic characteristics have remained relatively comparable across each year’s cohort. Both before and after the prioritization changes, between 40 percent and 50 percent of recipients were age 30 or over, with about one quarter each in the age 20 to 24 group and age 25 to 29 group. Similarly, about two–thirds of recipients in each year were female and about one–third were male, with no significant changes across the period. There has been a small decrease in the proportion of recipients who were employed when they applied for the grant—from 65 percent to 60 percent—even though changes required by Chapter 692 to prioritize grants for long–term unemployed applicants have not yet been put in place.

Figure 7

Cal Grant C Recipient Pool Largely Unchanged

|

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

|

|

Age |

|||||

|

30 or over |

50% |

48% |

49% |

47% |

42% |

|

25 to 29 |

25 |

26 |

24 |

22 |

24 |

|

20 to 24 |

22 |

24 |

23 |

25 |

29 |

|

19 or under |

3 |

2 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

|

Gender |

|||||

|

Female |

65% |

67% |

63% |

64% |

67% |

|

Male |

35 |

33 |

37 |

36 |

33 |

|

Applicant Employment Status |

|||||

|

Employed |

65% |

64% |

60% |

57% |

60% |

Premature to Assess Whether Criteria Have Affected Participant Outcomes

Too Early to Draw Conclusions About Recent Grantees. The Legislature asked us to report on the extent to which Cal Grant C recipients have been successfully placed in jobs that meet local, regional, or state workforce needs since the prioritization criteria were implemented. Employment data, however, tend to lag several years, and as such largely are not yet available for recent grant cohorts. Additionally, many recent grantees still are pursuing certificates and degrees supported by the grants, and therefore likely are not yet fully participating in the workforce. (Later, we discuss available employment data from previous Cal Grant C cohorts.)

Some Shifts in Program Choices. . . While employment data for the 2012–13 Cal Grant C cohort generally are not yet available, program data for these students reveal some interesting trends. Figure 8 shows the ten most common certificate programs for CCC students who received a Cal Grant C in 2012–13. (These data are limited to the roughly 40 percent of this grant cohort who have already completed a certificate or degree.) As shown, most of these program areas relate to—and could help lead to employment in—at least one of the occupations prioritized by CSAC. The figure also provides a comparison of how common these program areas were for students who received Cal Grant C grants in 2008‑09 and subsequently completed a CCC certificate. While several programs were top choices across both cohorts (including registered nursing, licensed vocational nursing, and child development), certain programs saw a notable increase in popularity across the years (including auto technology, administration of justice, and culinary arts).

Figure 8

Increasing Share of Grantees Received Certificates Related to Prioritized Occupationsa

|

Type of Program Certificate or Degree |

Rank for |

Change |

Related Prioritized Occupation |

|

Registered nursing |

1 |

0 |

Registered nurses |

|

Auto technology |

2 |

+6 |

Auto technicians and mechanics |

|

Licensed vocational nursing |

3 |

0 |

Licensed practical and licensed vocational nurses |

|

Child development/early care and education |

4 |

0 |

Preschool teachers |

|

Administration of justice |

5 |

+8 |

Police and sheriff’s patrol officers |

|

Biological and physical sciences (and mathematics) |

6 |

+1 |

None |

|

Culinary arts |

7 |

+12 |

Restaurant cooks |

|

Transfer studies |

8 |

+6 |

None |

|

Office technology/office computer applications |

9 |

0 |

Computer and computer support specialists, medical secretaries |

|

Paralegal |

10 |

+8 |

Paralegals and legal assistants |

|

aBased on data from California Community Colleges. Data from other institutions are not available. |

|||

. . . But Causes Still Unclear. There are a number of possible explanations for why 2012‑13 Cal Grant C recipients were more likely to pursue certificates or degrees in program areas that relate to CSAC’s prioritized occupations, as compared to the 2008–09 cohort. One possibility is that the prioritization criteria implemented in 2012–13 resulted in a larger pool of students pursuing the emphasized occupations. If true, this would suggest the criteria led to the intended policy outcome of more support for students who pursue—and perhaps even steering more students into—high need, growth, and/or wage occupations (as defined by CSAC). These program trends, however, also could be a reflection of the changing job market and of students independently choosing to pursue more productive occupations. Additional data would be necessary to determine what influence the prioritization criteria are having on students’ program choices.

No Notable Effects Resulting From Change to Allowable Uses of Grants

Legislation May Have Intended to Increase Grants for CCC Students. . . One change contained in Chapter 692 may not be having its intended effect. As described earlier, Cal Grant C is allocated in two separate amounts—$2,462 for tuition and fees, and $547 for books and supplies—but because of fee waivers, students attending CCC are only eligible to receive the smaller grant for books and supplies. Also noted earlier, Chapter 692 included language that expanded the allowable uses of Cal Grant C to include living expenses. According to representatives from the author’s office and certain stakeholders who were involved in developing the legislation, this change was intended to increase the amount of Cal Grant C aid that CCC students could receive, potentially up to the full $3,009 combined grant.

. . . However, State Agencies Did Not Interpret Language Change to Affect Grant Amounts. The Department of Finance and CSAC do not believe the language contained in Chapter 692 expands allowable grant amounts for CCC students, and therefore have not implemented associated changes. Three points support their interpretation. First, the legislation is unclear as to which component of the grant (the tuition amount or the books amount) can now also be used for living expenses. Second, Chapter 692 did not alter the budget bill language that designates the amounts and uses for the two components of Cal Grant C. (Statute stipulates that the maximum grant amount shall be determined in the annual budget act.) Third, the legislative analyses summarizing the version of SB 1028 that was enacted did not highlight an increase to CCC student grant amounts as a significant effect of the bill.

Completing Course of Study Is Important Indicator of Success

While meaningful outcome data for the most recent cohorts of Cal Grant C recipients are not yet available, data from earlier cohorts reveal certain trends that likely will continue even after implementation of the recent Cal Grant C changes. Below, we discuss outcome data from students who attended CCC programs and received Cal Grant C grants in 2008–09, 2009–10 or 2010–11. (Comparable data are not available for students attending programs other than CCC.)

Completing the Course of Study Quickly Is an Indicator for Ultimate Completion. Data suggest that if Cal Grant C recipients do not complete their certificate program within the first two years after receiving their grant, they are much less likely to complete at all. Only about half of all CCC–going Cal Grant C recipients ultimately earn a program degree or certificate. (This is comparable to overall completion rates for CCC students.) Typically, about 20 percent of CCC Cal Grant C recipients complete their program within the first year of receiving the grant, about 20 percent in the second year, and 8 percent in the third year. Only a very small percentage end up completing awards in subsequent years.

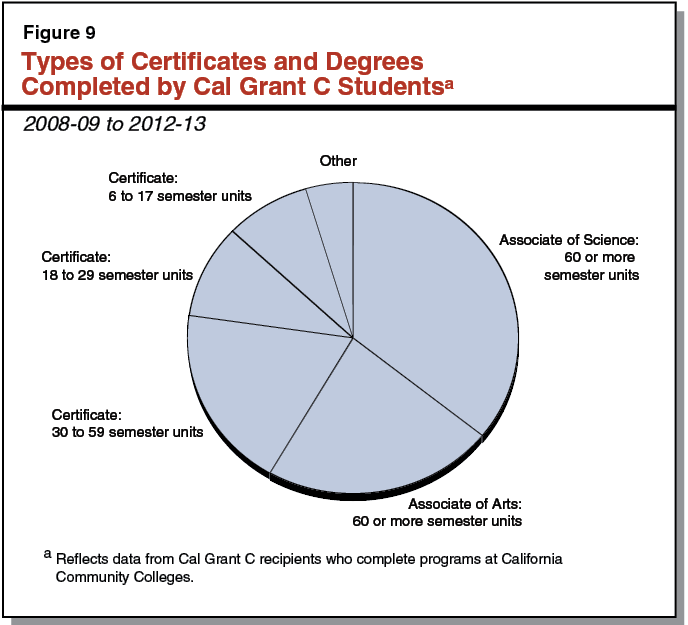

Majority of CCC Program Completers Achieve Associate Degrees. While about half of Cal Grant C recipients at CCC do not complete their course of study, most of those who do achieve longer–term certificates and degrees, which generally lead to higher–paying jobs than shorter–term certificates. As shown in Figure 9, about 60 percent of Cal Grant C recipients who complete a course of study at CCC achieve an associate degree, such as an Associate of Science in Nursing, which typically requires two years or more of coursework. An additional 20 percent receive a certificate requiring between 30 and 59 semester units, such as a certificate preparing a student to become a licensed vocational nurse, which requires between one and two years of coursework. Relatively fewer students receive short–term certificates, such as a 6–unit certificate preparing a student to take a nurse’s assistant license exam.

Completing the Course of Study Is an Indicator Both for Employment . . . Completing a CCC certificate or degree program seems to make a positive difference in employment rates for Cal Grant C recipients. As displayed earlier, typically between 60 percent and 65 percent of Cal Grant C recipients are employed when they first apply for the grant. Our analysis reveals that these employment rates remain unchanged for grant recipients who do not complete their programs. Specifically, about two–thirds of non–completers were employed three years after receiving the grant. In contrast, three–quarters of Cal Grant C recipients who completed a CCC program were employed three years after receiving their grants.

. . . And for Employment in Higher Skilled Jobs. Employment data suggest that completing a CCC certificate or degree program also can lead to Cal Grant C recipients finding employment in higher skill, higher wage types of jobs. Figure 10 shows the top sectors for employed Cal Grant C recipients who completed CCC programs within the past five years. Generally, about four in ten of this group works in one of these sectors. (While the exact ranking of these sectors varies somewhat across different years of employment data and grant cohorts, they consistently are among the most common sectors in recent years.) Work in hospitals is by far the most prevalent (nearly 15 percent of all employed program completers) in every year of data, with three other health–related settings (doctors’ offices, services for the elderly and disabled, and skilled nursing facilities) also among the most common choices. These trends are unsurprising given the large share of grantees who receive certificates in registered and licensed vocational nursing (as shown earlier in Figure 8). While data show that Cal Grant C recipients who do not complete their CCC programs of study but are employed also work in many of the fields displayed in Figure 10, they are more likely to be employed in the lower–skill sectors such as temporary help, as well as service sectors like hotels and supermarkets.

Figure 10

Most Frequent Employment Sectors For Employed Cal Grant C Recipients

2011 Through 2013

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Recommendations

Focus Future Efforts on Improving Program Completion Rates for Students in Vocational Programs. We believe the next steps in targeting the Cal Grant C program towards meeting state workforce needs should focus on helping grantees complete their training programs. The compelling evidence that completing a training program leads to more successful employment outcomes highlights the missed opportunities (and foregone state resources) for the roughly one–half of Cal Grant C recipients who fail to complete their programs. The CCC currently has several initiatives underway to improve student outcomes (including increasing completion rates). We recommend the Legislature ensure that these efforts include adequate focus on students enrolled in career technical programs as well as students preparing to transfer to a four–year college. A forthcoming report from a CCC task force on workforce preparation, expected this fall, will include recommendations for improving completion of workforce certificates. The Legislature could support implementation of recommended reforms through legislation, as it did for recent Student Success Task Force recommendations and transfer reforms in 2010 and 2013. Another strategy the Legislature could consider is increasing Cal Grant C amounts for CCC students (as discussed in the next paragraph). Research shows that working more than 20 hours per week is associated with lower academic performance, longer time to degree, and lower persistence and completion rates. Helping cover living expenses could allow students to work fewer hours while studying and therefore finish their courses of study more quickly and at higher rates.

If Legislature Wants to Increase Grant Amounts for CCC Students, Make Change Through the Budget. We believe additional clarification is needed should the Legislature wish to make CCC students eligible for larger Cal Grant C grants. (As discussed earlier, differing interpretations exist regarding whether Chapter 692 was meant to provide CCC students with access to Cal Grant C grants worth up to $3,009.) Specifically, we believe grant modifications would need to be made in the budget act provisional language that specifies the amounts and uses for Cal Grants. If the Legislature opts to increase individual grant amounts, it also will need to determine whether it wants to (1) maintain existing spending levels and provide grants to fewer students, or (2) increase overall spending for Cal Grant C in order to provide the larger grants to the same number of students. (A statutory amendment would be required to change the maximum number of awards.)

Continue to Monitor Effects of Prioritization Criteria Before Making Further Refinements. We recommend the Legislature hold off on making additional refinements to Cal Grant C prioritization criteria until more data are available on the effects of the recent changes. How the prioritization criteria put in place by Chapter 627 affected recipient outcomes still is unknown, and CSAC has yet to fully implement the changes included in Chapter 692. Additionally, as long the number of Cal Grant C applicants remains so low that nearly all applicants receive grant offers, criteria to prioritize among applicants will have a limited effect on the recipient pool. In lieu of making additional refinements to selecting Cal Grant C recipients, we believe the state will get a better return on its investment from ensuring those recipients—whoever they are—complete their courses of study.

Shift Ongoing Reporting Requirements Related to Cal Grant C to CSAC. After we provide a companion to this report in 2017, we recommend the Legislature shift responsibility to CSAC for any subsequent Cal Grant C updates it requires. The effects of Chapter 627 are not yet apparent and many of the changes included in Chapter 692 have not yet been put in place. As such, we view this report as an initial summary, and believe providing an updated analysis—potentially with additional recommendations drawn from our findings—in two years could be helpful to the Legislature. Statute, however, currently requires that we report to the Legislature every two years. Absent future policy changes, we do not believe future reports will necessitate a comparable level of legislative analysis from our office, but rather could consist of data updates to aid the Legislature in monitoring the Cal Grant C program. We believe CSAC could provide such updates. Moreover, given CSAC compiled much of the information we used to prepare this report (and now is beginning to compile additional employment outcome data on Cal Grant C recipients as required by statute), we believe the commission is well–positioned to provide any summary data the Legislature requires on Cal Grant C in the future.

Conclusion

Although it represents a relatively small component of California’s suite of student aid programs—both in terms of spending and number of participants—Cal Grant C has the important objective of helping to develop the state’s workforce. While data suggest the program may contribute to better employment options for those recipients who ultimately receive a certificate or degree, these successes are offset by lesser outcomes among the high proportion of students who do not complete their courses of study. Subsequent years of data may reveal whether recent changes implemented by the Legislature will meet the intended goal of better focusing Cal Grant C on strategic and emerging workforce needs. In the meantime, we encourage the Legislature to dedicate additional effort towards helping grant recipients complete their training programs so they can qualify for higher skilled—and higher paying—jobs.

Appendix

Cal Grant C Statute as Amended by Chapter 627, Statutes of 2011 and Chapter 692, Statutes of 2014

Education Code Title 3, Division 5, Part 42, Chapter 1.7, Article 6

69439 (a) For the purposes of this section, the following terms have the following meanings:

(1) “Career pathway” has the same meaning as set forth in Section 88620.

(2) “Economic security” has the same meaning as set forth in Section 14005 of the Unemployment Insurance Code.

(3) “Industry cluster” has the same meaning as set forth in Section 88620.

(4) “Long–term unemployed” means, with respect to an award applicant, a person who has been unemployed for more than 26 weeks at the time of submission to the commission of his or her application.

(5) “Occupational or technical training” means that phase of education coming after the completion of a secondary school program and leading toward recognized occupational goals approved by the commission.

(b) A Cal Grant C award shall be utilized only for occupational or technical training in a course of not less than four months. There shall be the same number of Cal Grant C awards each year as were made in the 2000–01 fiscal year. The maximum award amount and the total amount of funding shall be determined each year in the annual Budget Act.

(c) The commission may use criteria it deems appropriate in selecting students to receive grants for occupational or technical training and shall give special consideration to the social and economic situations of the students applying for these grants, giving additional weight to disadvantaged applicants, applicants who face economic hardship, and applicants who face particular barriers to employment. Criteria to be considered for these purposes shall include, but are not limited to, all of the following:

(1) Family income and household size.

(2) Student’s or the students’ parent’s household status, including whether the student is a single parent or child of a single parent.

(3) The employment status of the applicant and whether the applicant is unemployed, giving greater weight to the long–term unemployed.

(d) The Cal Grant C award recipients shall be eligible for renewal of their grants until they have completed their occupational or technical training in conformance with terms prescribed by the commission. A determination by the commission for a subsequent award year that the program under which a Cal Grant C award was initially awarded is no longer deemed to receive priority shall not affect an award recipient’s renewal. In no case shall the grants exceed two calendar years.

(e) Cal Grant C awards may be used for institutional fees, charges, and other costs, including tuition, plus training–related costs, such as special clothing, local transportation, required tools, equipment, supplies, books, and living expenses. In determining the individual award amounts, the commission shall take into account the financial means available to the student to fund his or her course of study and costs of attendance as well as other state and federal programs available to the applicant.

(f) (1) To ensure alignment with the state’s dynamic economic needs, the commission, in consultation with appropriate state and federal agencies, including the Economic and Workforce Development Division of the Office of the Chancellor of the California Community Colleges and the California Workforce Investment Board, shall identify areas of occupational and technical training for which students may utilize Cal Grant C awards. The commission, to the extent feasible, shall also consult with representatives of the state’s leading competitive and emerging industry clusters, workforce professionals, and career technical educators, to determine which occupational training programs and industry clusters should be prioritized.

(2) (a) Except as provided in subparagraph (B), the areas of occupational and technical training developed pursuant to paragraph (1) shall be regularly reviewed and updated at least every five years, beginning in 2012.

(b) By January 1, 2016, the commission shall update the priority areas of occupational and technical training.

(3) (a) The commission shall give priority in granting Cal Grant C awards to students pursuing occupational or technical training in areas that meet two of the following criteria pertaining to job quality:

(i) High employer need or demand for the specific skills offered in the program.

(ii) High employment growth in the occupational field or industry cluster for which the student is being trained.

(iii) High employment salary and wage projections for workers employed in the occupations for which they are being trained.

(iv) The occupation or training program is part of a well–articulated career pathway to a job providing economic security.

(b) To receive priority pursuant to subparagraph (A), at least one of the criteria met shall be specified in clause (iii) or (iv) of that subparagraph.

(g) The commission shall determine areas of occupational or technical training that meet the criteria described in paragraph (3) of subdivision (f) in consultation with the Employment Development Department, the Economic and Workforce Development Division of the Office of the Chancellor of the California Community Colleges, and the California Workforce Investment Board using projections available through the Labor Market Information Data Library. The commission may supplement the analyses of the Employment Development Department’s Labor Market Information Data Library with the labor market analyses developed by the Economic and Workforce Development Division of the Office of the Chancellor of the California Community Colleges and the California Workforce Investment Board, as well as the projections of occupational shortages and skills gap developed by industry leaders. The commission shall publish, and retain, on its Internet Web site a current list of the areas of occupational or technical training that meet the criteria described in paragraph (3) of subdivision (f), and update this list as necessary.

(h) Using the best available data, the commission shall examine the graduation rates and job placement data, or salary data, of eligible programs. Commencing with the 2014–15 academic year, the commission shall give priority to Cal Grant C award applicants seeking to enroll in programs that rate high in graduation rates and job placement data, or salary data.

(i) (1) The commission shall consult with the Employment Development Department, the Office of the Chancellor of the California Community Colleges, the California Workforce Investment Board, and the local workforce investment boards to develop a plan to publicize the existence of the grant award program to California’s long–term unemployed to be used by those consulting agencies when they come in contact with members of the population who are likely to be experiencing long–term unemployment. The outreach plan shall use existing administrative and service delivery processes making use of existing points of contact with the long–term unemployed. The local workforce investment boards are required to participate only to the extent that the outreach efforts are a part of their existing responsibilities under the federal Workforce Investment Act of 1998 (Public Law 105–220).

(2) The commission shall consult with the Workforce Services Branch of the Employment Development Department, the Office of the Chancellor of the California Community Colleges, the California Workforce Investment Board, and the local workforce investment boards to develop a plan to make students receiving awards aware of job search and placement services available through the Employment Development Department and the local workforce investment boards. Outreach shall use existing administrative and service delivery processes making use of existing points of contact with the students. The local workforce investment boards are required to participate only to the extent that the outreach efforts are a part of their existing responsibilities under the federal Workforce Investment Act of 1998 (Public Law 105–220).

(j) (1) Notwithstanding Section 10231.5 of the Government Code, the Legislative Analyst’s Office shall submit a report to the Legislature on the outcomes of the Cal Grant C program on or before April 1, 2015, and on or before April 1 of each odd–numbered year thereafter. This report shall include, but not necessarily be limited to, information on all of the following:

(a) The age, gender, and segment of attendance for recipients in two prior award years.

(b) The occupational and technical training program categories prioritized.

(c) The number and percentage of students who received selection priority as defined in paragraph (3) of subdivision (f).

(d) The extent to which recipients in these award years were successfully placed in jobs that meet local, regional, or state workforce needs.

(2) For the report due on or before April 1, 2015, the Legislative Analyst’s Office shall include data for two additional prior award years and shall compare the mix of occupational and technical training programs and institutions in which Cal Grant C award recipients enrolled before and after implementation of subdivision (f).

(3) A report to be submitted pursuant to this subdivision shall be submitted in compliance with Section 9795 of the Government Code.