Ballot Pages

Propositions on the November 6, 2018 Ballot

November 6, 2018Proposition 8

Authorizes State Regulation of Kidney Dialysis Clinics. Limits Charges for Patient Care. Initiative Statute. Initiative Statute.

Yes/No Statement

A YES vote on this measure means: Kidney dialysis clinics would have their revenues limited by a formula and could be required to pay rebates to certain parties (primarily health insurance companies) that pay for dialysis treatment.

A NO vote on this measure means: Kidney dialysis clinics would not have their revenues limited by a formula and would not be required to pay rebates.

Summary of Legislative Analyst’s Estimate of Net State and Local Government Fiscal Impact

-

Overall annual effect on state and local governments ranging from net positive impact in the low tens of millions of dollars to net negative impact in the tens of millions of dollars.

Ballot Label

Fiscal Impact: Overall annual effect on state and local governments ranging from net positive impact in the low tens of millions of dollars to net negative impact in the tens of millions of dollars.

Background

Dialysis Treatment

Kidney Failure. Healthy kidneys filter a person’s blood to remove waste and extra fluid. Kidney disease refers to when a person’s kidneys do not function properly. Over time, a person may develop kidney failure, also known as “end-stage renal disease.” This means that the kidneys no longer function well enough for the person to survive without a kidney transplant or ongoing treatment referred to as dialysis.

Dialysis Mimics Normal Kidney Functions. Dialysis artificially mimics what healthy kidneys do. Most people on dialysis undergo hemodialysis, a form of dialysis in which blood is removed from the body, filtered through a machine to remove waste and extra fluid, and then returned to the body. A hemodialysis treatment lasts about four hours and typically occurs three times per week.

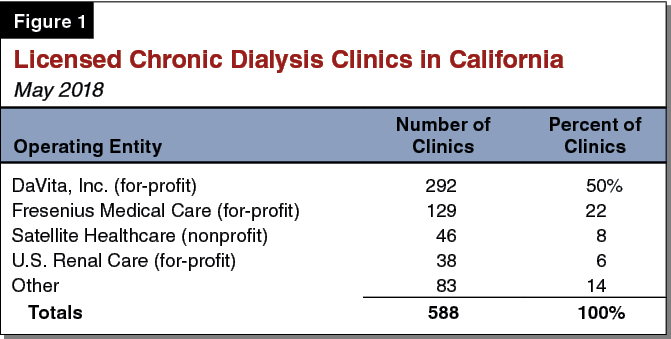

Most Dialysis Patients Receive Treatment in Clinics. Individuals with kidney failure may receive dialysis treatment at hospitals or in their own homes, but most receive treatment at chronic dialysis clinics (CDCs). As of May 2018, 588 licensed CDCs in California provided treatment to roughly 80,000 patients each month. Each CDC operates an average of 22 dialysis stations, with each station providing treatment to one patient at a time. The California Department of Public Health (DPH) is responsible for licensing and inspecting CDCs. Various entities own and operate CDCs. As shown in Figure 1, two private for-profit entities operate and have at least partial ownership of the majority of CDCs in California.

Paying for Dialysis Treatment

Payment for Dialysis Treatment Comes From a Few Main Sources. We estimate that CDCs have total revenues of roughly $3 billion annually from their operations in California. These revenues consist of payments for dialysis treatment from a few main sources, or “payers”:

-

Medicare. This federally funded program provides health coverage to most people age 65 and older and certain younger people who have disabilities. Federal law generally makes people with kidney failure eligible for Medicare coverage regardless of age or disability status. Medicare pays for dialysis treatment for the majority of people on dialysis in California.

-

Medi-Cal. The federal-state Medicaid program, known as Medi-Cal in California, provides health coverage to low-income people. The state and the federal government share the costs of Medi-Cal. Some people qualify for both Medicare and Medi-Cal. For these people, Medicare covers most of the payment for dialysis treatment as the primary payer and Medi-Cal covers the rest. For people enrolled only in Medi-Cal, the Medi-Cal program is solely responsible to pay for dialysis treatment.

-

Group and Individual Health Insurance. Many people in the state have group health insurance coverage through an employer or another organization (such as a union). The California state government, the state’s two public university systems, and many local governments in California provide group health insurance coverage for their current workers, eligible retired workers, and their families. Some people without group health insurance purchase health insurance individually. Group and individual health insurance coverage is often provided by a private insurer that receives a premium payment in exchange for covering the costs of an agreed-upon set of health care services. When an insured person develops kidney failure, that person can usually transition to Medicare coverage. Federal law requires that a group insurer remain the primary payer for dialysis treatment for a “coordination period” that lasts 30 months.

Group and Individual Health Insurers Typically Pay Higher Rates for Dialysis

Than Government Programs. The rates that Medicare and Medi-Cal pay for dialysis treatment are relatively close to the average cost for CDCs to provide a dialysis treatment and are largely determined by regulation. In contrast, group and individual health insurers establish their rates by negotiating with CDCs. The rates paid by these insurers depend on the relative bargaining power of insurers and the CDCs. On average, group and individual health insurers pay multiple times what government programs pay for dialysis treatment.

Proposal

Requires Clinics to Pay Rebates When Total Revenues Exceed a Specified Cap. Beginning in 2019, the measure requires CDCs each year to calculate the amount by which their revenues exceed a specified cap. The measure then requires CDCs to pay rebates (that is, give money back) to payers, excluding Medicare and other government payers, in the amount that revenues exceed the cap. The more a payer paid for treatment, the larger the rebate the payer would receive.

Revenue Cap Based on Specified CDC Costs. The revenue cap established by the measure is equal to 115 percent of specified “direct patient care services costs” and “health care quality improvement costs.” These include the cost of such things as staff wages and benefits, staff training and development, drugs and medical supplies, facilities, and electronic health information systems. Hereafter, we refer to these costs as “allowable,” meaning they can be counted toward determining the revenue cap. Other costs, such as administrative overhead, would not be counted toward determining the revenue cap.

Interest and Penalties on Rebated Amounts. In addition to paying any rebates, CDCs would be required to pay interest on the rebate amounts, calculated from the date of payment for treatment. CDCs would also be required to pay a penalty to DPH of 5 percent of the amount of any required rebates, up to a maximum penalty of $100,000.

Rebates Calculated at Owner/Operator Level. The measure specifies that rebates would be calculated at the level of a CDC’s “governing entity,” which refers to the entity that owns or operates the CDC (hereafter “owner/operator”). Some owner/operators have many CDCs in California, while others may own or operate a single CDC. For owner/operators with many CDCs, the measure requires them to add up their revenues and allowable costs across all of their CDCs in California. If the total revenues exceed 115 percent of total allowable costs across all of an owner/operator’s clinics, they would be required to pay rebates equal to the difference.

Legal Process to Raise Revenue Cap in Certain Situations. Both the California Constitution and the United States Constitution prohibit the government from taking private property (which includes the value of a business) without fair legal proceedings or fair compensation. A CDC owner/operator might try to prove in court that, in their particular situation, the required rebates would amount to taking the value of the business and therefore violate the state or federal constitution. If a CDC owner/operator is able to prove this, the measure outlines a process where the court would reduce the required rebates by just enough to no longer violate the constitution. The measure places on the CDC owner/operator the burden of identifying the largest amount of rebates that would be legal. The measure specifies that any adjustment in the rebate amount would apply for only one year.

Other Requirements. The measure requires that CDC owner/operators submit annual reports to DPH. These reports would list the number of dialysis treatments provided, the amount of allowable costs, the amount of the owner/operator’s revenue cap, the amount by which revenues exceed the cap, and the amount of rebates paid. The measure also prohibits CDCs from refusing to provide treatment to a person based on who is paying for the treatment.

DPH Required to Issue Regulations. The measure requires DPH to develop and issue regulations to implement the measure’s provisions within 180 days of the measure’s effective date. In particular, the measure allows DPH to identify through regulation additional CDC costs that would count as allowable costs, which could serve to reduce the amount of any rebates otherwise owed by CDCs.

Fiscal Effects

Measure Would Reduce CDC Profitability

Currently, it appears that CDCs operating in California have revenues in excess of the revenue cap specified in the measure. Paying rebates in the amount of the excess would significantly reduce the revenues of CDC owner/operators. In the case of CDCs operated by for-profit entities (the majority of CDCs), this means the CDCs would be less profitable or could even be unprofitable. This could lead to changes in how dialysis treatment is provided in the state. These changes could have various effects on state and local government finances. As described below, the impact of the measure on CDCs and on state and local government finances is uncertain. This is because the impact would depend on future actions of (1) state regulators and courts in interpreting the measure and (2) CDCs in response to the measure. These future actions are difficult to predict.

Major Sources of Uncertainty

Uncertain Which Costs Are Allowable. The impact of the measure would depend on how allowable costs are defined. Including more costs as allowable would make revenue caps higher and allow CDCs to keep more of their revenues (by requiring smaller rebates). Including fewer costs as allowable would make revenue caps lower and allow clinics to keep less of their revenues (by requiring larger rebates). It is uncertain how DPH (as the state regulator involved in implementing and enforcing the measure) and courts would interpret the measure’s provisions defining allowable costs. For example, the measure specifies that the costs of staff wages and benefits are only allowable for “non-managerial” staff that provide direct care to dialysis patients. Federal law requires CDCs to maintain certain staff positions as a condition of receiving Medicare reimbursement. Some of these required positions—including the medical director and nurse manager—perform managerial functions but are also involved in direct patient care. The costs of these positions might not be considered allowable because the positions have managerial functions. On the other hand, the costs of these positions might be considered allowable because the positions relate to direct patient care.

Uncertain How CDCs Would Respond to the Measure. CDC owner/operators would likely respond to the measure by adjusting their operations in ways that limit, to the extent possible, the effect of the rebate requirement. They could do any of the following:

-

Increase Allowable Costs. CDC owner/operators might increase allowable costs, such as wages and benefits for non-managerial staff providing direct patient care. Increasing allowable costs would raise the revenue cap, reduce the amount of rebates owed, and potentially leave CDC owner/operators better off than if they were to leave allowable costs at current levels. This is because the amount of revenues that CDC owner/operators could retain would grow by more than the additional costs (the revenue cap would increase by 115 percent of additional allowable costs).

-

Reduce Other Costs. CDC owner/operators might also reduce, where possible, other costs that do not count toward determining the revenue cap (such as administrative overhead). This would not change the amount of rebates owed, but it would improve the CDCs’ profitability.

-

Seek Adjustments to Revenue Cap. If CDC owner/operators believe they cannot achieve a reasonable return on their operations even after making adjustments as described above, they might try to challenge the rebate provision in court to get a higher revenue cap as outlined in the measure. If such a challenge were successful, some CDC owner/operators might have a higher revenue cap and owe less in rebates in some years.

-

Scale Back Operations. In some cases, owner/operators might decide to open fewer new CDCs or close some CDCs if the amount of required rebates is large and reduced revenues do not provide sufficient return on investment to expand or remain in the market. If this takes place, other providers would eventually need to step in to meet the demand for dialysis. These other providers might operate less efficiently (have higher costs). Some other providers could potentially be exempt from the provisions of the measure if they do not operate under a CDC license (for example, hospitals). Such broader changes in the dialysis industry are difficult to predict.

Impact of Rebate Provisions on State and Local Finances

We estimate that, without actions taken by CDCs in response to the measure, potential rebates owed could reach several hundred million dollars. Depending on the factors discussed above, the measure’s rebate provisions could have several types of effects on state and local finances.

Measure Could Generate State and Local Government Employee Health Care Savings . . . To the extent that CDCs pay rebates, state and local government costs for employee health care could be reduced. As noted previously, the measure excludes government payers from receiving rebates. However, state and local governments often contract with private health insurers to provide coverage for their employees. As private entities, these insurers might be eligible for rebates under the measure. Even if they are not eligible for rebates, they would likely still be in a position to negotiate lower rates with CDC owner/operators. These insurers might pass some or all of these savings on to government employers in the form of reduced health insurance premiums.

. . . Or Costs. On the other hand, as described above, CDCs might respond to the measure by increasing allowable costs. If CDCs increase allowable costs enough, rates that health insurers pay for dialysis treatment might increase above what they would have been in the absence of the measure. If this occurs, insurers might pass some or all of these higher costs on to government employers in the form of increased health insurance premiums.

State Medi-Cal Cost Pressures. The Medi-Cal program also contracts with private insurers to provide dialysis coverage for some of its enrollees. Similar to health insurers that provide coverage for government employees, private insurers that contract with Medi-Cal might also receive rebates (if they are determined to be eligible) or might be able to negotiate lower rates with CDC owner/operators. Some or all of these savings might be passed on to the state. However, because rates paid to CDCs by these insurers are relatively low, such savings would likely be limited. On the other hand, if CDCs respond to the measure by increasing allowable costs, the average cost of a dialysis treatment would increase. This would put upward pressure on Medi-Cal rates and could result in increased state costs.

Changes to State Tax Revenues. To the extent the measure’s rebate provisions operate to reduce the net income of CDC owner/operators, the measure would likely reduce the amount of income taxes that for-profit owner/operators are required to pay to the state. This reduced revenue could be offset, to an unknown extent, by various other changes to state revenues. For example, additional income tax revenue could be generated if CDCs respond to the measure by increasing spending on allowable staff wages.

In Light of Significant Uncertainty, Overall Effect on State and Local Finances Is Unclear. Different interpretations of the measure’s provisions and different CDC responses to the measure would lead to different impacts for state and local governments. In light of significant uncertainty about how the measure may be interpreted and how CDCs may respond, a range of possible net impacts on state and local government finances is possible.

Overall Effect Could Range From Net Positive Impact in the Low Tens of Millions of Dollars . . . If the measure is ultimately interpreted to have a broader, more inclusive definition of allowable costs, such as by including costs for nurse managers and medical directors, the amount of rebates CDC owner/operators are required to pay would be smaller. Under this interpretation, it is more likely that CDC owner/operators would respond with relatively modest changes to their cost structures. In this scenario, state and local government costs for employee health benefits could be reduced. These savings would likely be partially offset by a net reduction in state tax revenues. Overall, we estimate the measure could have a net positive impact on state and local government finances reaching the low tens of millions of dollars annually in this scenario.

. . . To Net Negative Impact in the Tens of Millions of Dollars. If the measure is ultimately interpreted to have a narrower, more restrictive definition of allowable costs, the amount of rebates CDC owner/operators are required to pay would be greater. Under this interpretation, it is more likely that CDC owner/operators would respond with more significant changes to their cost structures, particularly by increasing allowable costs. CDC owner/operators would also be more likely to seek adjustments to the revenue cap or scale back operations in the state. In this scenario, state and local government costs for employee health benefits and state Medi-Cal costs could increase. State tax revenues could also be reduced. Overall, we estimate the measure could have a net negative impact reaching the tens of millions of dollars annually in this scenario.

Other Potential Fiscal Impacts. The scenarios described above represent our best estimate of the range of the measure’s likely fiscal impacts. However, other fiscal impacts are possible. As an example, if CDCs respond to the measure by scaling back operations in the state, some dialysis patients’ access to dialysis treatment could be disrupted in the short run. This could lead to health complications that result in admission to a hospital. To the extent that dialysis patients are hospitalized more frequently because of the measure, state costs—particularly in Medi-Cal—could increase significantly in the short run.

Administrative Impact

This measure imposes new responsibilities on DPH. We estimate that the annual cost to fulfill these new responsibilities likely would not exceed the low millions of dollars annually. The measure requires DPH to adjust the annual licensing fee paid by CDCs (currently set at about $3,400 per facility) to cover these costs. Some of these administrative costs may also be offset by penalties paid by CDCs related to rebates or failure to comply with the measure’s reporting requirements. The amount of any offset is unknown.