Ballot Pages

Propositions on the November 8, 2016 Ballot

November 8, 2016Proposition 61

State Prescription Drug Purchases. Pricing Standards.

Yes/No Statement

A YES vote on this measure means: State agencies would generally be prohibited from paying more for any prescription drug than the lowest price paid by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs for the same drug.

A NO vote on this measure means: State agencies would continue to be able to negotiate the prices of, and pay for, prescription drugs without reference to the prices paid by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Summary of Legislative Analyst’s Estimate of Net State and Local Government Fiscal Impact

Potential for state savings of an unknown amount depending on (1) how the measure’s implementation challenges are addressed and (2) the responses of drug manufacturers regarding the provision and pricing of their drugs.

Ballot Label

Fiscal Impact: Potential for state savings of an unknown amount depending on (1) how the measure’s implementation challenges are addressed and (2) the responses of drug manufacturers regarding the provision and pricing of their drugs.

Background

The State Payments for Prescription Drugs

State Pays for Prescription Drugs Under Many Different State Programs. Typically, the state pays for prescription drugs under programs that provide health care or health insurance to certain state populations. For example, the state pays for prescription drugs through the health care coverage it provides to the state’s low-income residents through the Medi-Cal program and to current and retired state employees. The state also provides and pays for the health care of prison inmates, including their prescription drug costs.

State Pays for Prescription Drugs in a Variety of Ways. In some cases, the state purchases prescription drugs directly from drug manufacturers. In other cases, the state pays for prescription drugs even though it is not the direct purchaser of them. For example, the state reimburses retail pharmacies for the cost of prescription drugs purchased by the pharmacies and dispensed to individuals enrolled in certain state programs.

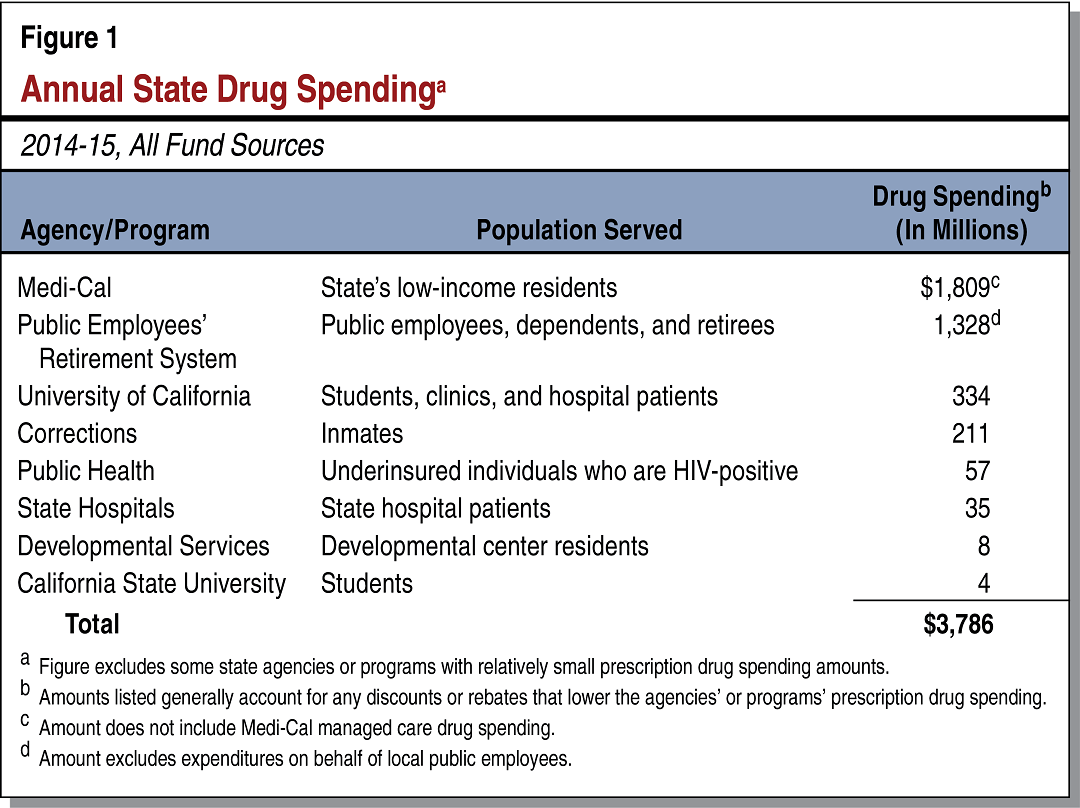

Annual State Drug Expenditures Totaled Almost $3.8 Billion in 2014-15. As shown in Figure 1, the state spent almost $3.8 billion on prescription drugs in 2014-15 under a variety of state programs. State funds pay for roughly half of overall state prescription drug spending, and the remainder is paid with federal and other nonstate revenues.

Prescription Drug Pricing in General

Prices Actually Paid Often Differ From the Drugs’ “List Prices.” Prescription drugs sold in the United States have list prices that are similar to the manufacturer’s suggested retail price (MSRP) for automobiles. Purchasers of the drugs typically negotiate the prices and often receive discounts. As a result, the final price paid for a prescription drug is typically lower than its list price.

Different Payers Often Pay Different Prices for the Same Prescription Drug. Often there is no single price paid by all payers for a particular prescription drug. Instead, different payers may regularly pay different prices for the same drug, which reflect the results of negotiations between the drugs’ buyers and sellers. For example, two different insurance companies may pay different prices for the same drug, as may two separate state agencies such as the California Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) and the California Department of Public Health.

Prices Paid for Prescription Drugs Are Often Subject to Confidentiality Agreements. Prescription drug purchase agreements often contain confidentiality clauses that are intended to prohibit public disclosure of the agreed prices. As a result, the prescription drug prices paid by a particular entity, including a government agency, may be unavailable to the public.

State Prescription Drug Pricing

State Strategies to Reduce Prescription Drug Prices. California state agencies pursue a variety of strategies to reduce the prices they pay for prescription drugs, which typically involve negotiating with drug manufacturers and wholesalers. The particular strategies vary depending on program structure and the manner in which the state programs pay for drugs. For example, multiple California state departments jointly negotiate drug prices with manufacturers. By negotiating as a single, larger entity, the participating state departments are able to obtain lower drug prices. Another state strategy is to negotiate discounts from drug manufacturers in exchange for reducing the overall administrative burden on doctors prescribing these manufacturers’ drugs.

United States Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) Prescription Drug Pricing

VA Provides Health Care to Veterans. The VA provides comprehensive health care to approximately nine million veterans nationwide. In doing so, the VA generally purchases the prescription drugs that it makes available to VA health care beneficiaries.

Programs to Reduce Federal Prescription Drug Expenditures. The federal government has established discount programs that place upper limits on the prices paid for prescription drugs by selected federal payers, including the VA. These programs generally result in lower prices than those available to private payers.

VA Obtains Additional Discounts From Drug Manufacturers or Sellers. On top of the federal discount programs described above, the VA often negotiates additional discounts from drug manufacturers or sellers that lower its prices below what other federal departments pay. Manufacturers or sellers provide these discounts in return for their drugs being made readily available to VA patients.

VA Publishes Some of Its Prescription Drug Pricing Information. The VA maintains a public database that lists the prices paid by the VA for most of the prescription drugs it purchases. According to the VA, however, the database may not display the lowest prices paid for some of the drugs for which the VA obtains additional negotiated discounts. The VA may not publish this pricing information in the database due to confidentiality clauses that are included in certain drugs’ purchase agreements and are intended to prohibit public disclosure of the negotiated prices.

Proposal

Measure Sets an Upper Limit on Amount State Can Pay for Prescription Drugs. This measure generally prohibits state agencies from paying more for a prescription drug than the lowest price paid by the VA for the same drug after all discounts are factored in for both California state agencies and the VA.

Measure Applies Whenever the State Is the Payer of Prescription Drugs. The measure’s upper limit on state prescription drug prices applies regardless of how the state pays for the prescription drugs. It applies, for example, whether the state purchases prescription drugs directly from a manufacturer or instead reimburses pharmacies for the drugs they provide to enrollees of state programs.

Measure Exempts a Portion of the State’s Largest Health Care Program From Its Drug Pricing Requirements. The state’s Medi-Cal program offers comprehensive health coverage to the state’s low-income residents. The state operates Medi-Cal under two distinct service delivery systems: the fee-for-service system (which serves approximately 25 percent of Medi-Cal enrollees) and the managed care system (which serves approximately 75 percent of enrollees). While the measure applies to the fee-for-service system, it exempts the managed care system from its drug pricing requirements described above.

DHCS Required to Verify That State Agencies Are Complying With Measure’s Drug Pricing Requirements. The measure requires DHCS to verify that state agencies are paying the same or less than the lowest price paid by the VA on a drug-by-drug basis.

Fiscal Effects

By prohibiting the state from paying more for a prescription drug than the lowest price paid by the VA, there is the potential for the state to realize reductions in its drug costs. There are, however, major uncertainties concerning (1) the implementation of the measure’s lowest-cost requirement and (2) how drug manufacturers would respond in the market. We discuss these concerns below.

Potential Implementation Challenges Create Fiscal Uncertainty

Some VA Drug Pricing Information May Not Be Publicly Accessible. The measure generally requires that the prescription drug prices paid by the state not exceed the lowest prices paid by the VA on a drug-by-drug basis. As mentioned above, the VA’s public database information on the prices of the prescription drugs it purchases does not always identify the lowest prices the VA pays. This is because, at least for some drugs, the VA has negotiated a lower price than that shown in the public database and is keeping that pricing information confidential. It is uncertain whether the VA could be nonetheless required to disclose these lower prices to an entity—such as DHCS—requesting such information under a federal Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. A FOIA exemption covering trade secrets and financial information may apply to prevent the VA from having to disclose these currently confidential prices to the state.

Confidentiality of VA Drug Prices Could Compromise the State’s Ability to Implement the Measure. If the VA is legally allowed to keep some of its prescription drug pricing information confidential, DHCS would be unable to assess in all cases whether state agencies are paying less than or equal to the lowest price paid by the VA for the same drug. This would limit the state’s ability to implement the measure as it is written. However, to address challenges in implementing laws, courts sometimes grant state agencies latitude to implement laws to the degree that is practicable as long as implementation is consistent with the laws’ intent. For example, courts might allow the state to pay for drugs at a price not exceeding the lowest known price paid by the VA, rather than the actual lowest price, to allow the measure to be implemented.

Potential Confidentiality of Lowest VA Drug Prices Reduces but Does Not Eliminate Potential State Savings. The potential confidentiality of at least some of the lowest VA prices reduces but does not eliminate the measure’s potential to generate savings related to state prescription drug spending. Though pricing information may be unavailable for some of the VA’s lowest-priced prescription drugs, publicly available VA drug prices have historically been lower than the prices paid by some California state agencies for some drugs. To the extent that the VA’s publicly available drug prices for particular drugs are lower than those paid by California state agencies and manufacturers choose to offer these prices to the state, the measure would help the state achieve prescription drug-related savings.

Potential Drug Manufacturer Responses Limit Potential Savings

Drug Manufacturer Responses Under Measure Could Significantly Affect Fiscal Impact. In order to maintain similar levels of profits on their products, drug manufacturers would likely take actions that mitigate the impact of the measure. A key reason why drug manufacturers might take actions in response to the measure relates to how federal law regulates state Medicaid programs’ prescription drug prices. (Medi-Cal is California’s Medicaid program.) Federal law entitles all state Medicaid programs to the lowest prescription drug prices available to most public and private payers in the United States (excluding certain payers, such as the VA). If certain California state agencies receive VA prices, as the measure intends, this would set new prescription drug price limits at VA prices for all state Medicaid programs. As a result, the measure could extend the VA’s favorable drug prices to health programs serving tens of millions of additional people nationwide, placing added pressure on drug manufacturers to take actions to protect their profits under the measure.

Below are two possible manufacturer responses. (We note that manufacturers might ultimately pursue both strategies, while at the same time offering some drugs at favorable VA prices.)

-

Drug Manufacturers Might Raise VA Drug Prices. Knowing that the measure makes VA prices the upper limit for what the state can pay, drug manufacturers might choose to raise VA drug prices. This would allow drug manufacturers to continue to offer prescription drugs to state agencies while minimizing any reductions to their profits. Should manufacturers respond in this manner, potential savings related to state prescription drug spending would be reduced.

-

Drug Manufacturers Might Decline to Offer Lowest VA Prices to the State for Some Drugs. The measure places no requirement on drug manufacturers to offer prescription drugs to the state at the lowest VA prices. Rather, the measure restricts actions that the state can take (namely, prohibiting the state from paying more than the lowest VA prices for prescription drugs). Therefore, if manufacturers decide it is in their interest not to extend the VA’s favorable pricing to California state agencies (for example, to avoid consequences such as those described above), drug manufacturers could decline to offer the state some drugs purchased by the VA. In such cases, these drugs would be unavailable to most state payers. Instead, the state would be limited to paying for drugs that either the VA does not purchase or drugs that manufacturers will offer at the lowest VA prices. (However, to comply with federal law, Medi-Cal might have to disregard the measure’s price limits and pay for prescription drugs regardless of whether manufacturers offer their drugs at or below VA prices.) This manufacturer response could reduce potential state savings under the measure since it might limit the drugs the state can pay for to those that, while meeting the measure’s price requirements, are actually more expensive than those currently paid for by the state.

Summary of Overall Fiscal Effect

As discussed above, if adopted, the measure could generate annual state savings. However, the amount of any savings is highly uncertain as it would depend on (1) how the measure’s implementation challenges are addressed and (2) the uncertain market responses of drug manufacturers to the measure. As a result, the fiscal impact of this measure on the state is unknown. It could range from relatively little effect to significant annual savings. For example, if the measure lowered total state prescription drug spending by even a few percent, it would result in state savings in the high tens of millions of dollars annually.