January 2007

Each campus and medical center of the University of California (UC) periodically develops a long range development plan (LRDP) that guides its physical development—based on academic goals and projected student enrollment levels—for an established time horizon. This report reviews the process used by UC to prepare LRDPs and analyzes whether it adequately addresses the impacts that campus growth has on surrounding communities. We generally found a lack of accountability, standardization, and clarity in the current process, and recommend steps to make the process more transparent and effective (such as ensuring greater legislative oversight and public involvement in the development of an LRDP).

The state�s Master Plan for Higher Education (originally adopted by the Legislature in 1960 and periodically reviewed) assigns to the University of California (UC) the primary mission of providing undergraduate and graduate instruction in the liberal arts, sciences, and professional education. The plan directs UC to draw its entering freshmen from the top one-eighth (12.5�percent) of public high school graduates and to accept all qualified community college students. Such students are considered �eligible� for admission to the segment as a whole, but are not guaranteed admission to any particular campus. The Master Plan also specifies that UC is the primary state-supported academic agency for research.

Because the Master Plan promises access for eligible students, growth in enrollment demand (due to increases in the number of eligible high school graduates, for example) puts pressure on UC to increase enrollment and to expand infrastructure to accommodate the additional students. Each campus�s plans for growth are identified in its Long Range Development Plan (LRDP), which sets upper limits for broad campus parameters-such as student enrollment and number of employees-for 10 to 15 years into the future. The LRDP may also identify special infrastructure that might be required, such as athletic stadiums, parking garages, faculty and student housing, and nature reserves. Sometimes planned transportation systems are also identified-such as shuttle buses and dedicated bicycle and pedestrian circulation paths. The LRDP essentially defines the �outer envelope� for campus growth in the period covered by the plan.

In developing LRDPs, campuses consult surrounding communities in an attempt to achieve a mutually agreeable plan. In recent years, such agreement has sometimes been elusive, with differences of opinions over traffic, housing, and other potential impacts of planned campus growth. For example, some communities believe that a campus should only grow to the extent it pays for all the costs associated with mitigating off-campus impacts, while some UC campuses expect such costs to be shared with local government. In view of these disputes, our office analyzed whether UC�s LRDP process adequately addresses the impacts that campus growth has on surrounding communities.

In this report, we:

Review the purpose of LRDPs and the process used by UC to prepare them for its campuses and medical centers, including the extent to which the process incorporates local and community input.

Assess how much UC campuses would need to grow in future years to accommodate projected student enrollment.

Discuss the current process for mitigating off-campus impacts, including a review of the policies adopted by other states.

Identify issues for the Legislature to consider, including recommendations to improve UC�s LRDP process.

In preparing this report, we met with representatives from the UC Office of the President (UCOP) and from three UC campuses (Davis, Riverside, and Santa Cruz), in order to gain an in-depth understanding on how campuses prepare and implement their LRDPs. During our campus visits, we also met separately with neighborhood residents and local government officials (such as city council members and county supervisors) to learn about their concerns and involvement in the LRDP process. In addition, we interviewed officials from private universities in California and from public universities in other states regarding their development of long-range physical plans. Specifically, we examined the processes at Stanford University, University of the Pacific, Arizona State University, University of Colorado, State University of New York, University of Texas, and the University of Washington.

An LRDP is a land use plan that guides the physical development of a UC campus-such as the location of buildings and open space-for an established time horizon. (Although each of UC�s medical centers also has an LRDP, much of this report focuses on campus-level LRDPs.) When a campus is first being built, an initial LRDP is developed (commonly referred to as the �master plan�). Subsequent LRDPs for the campus are essentially updates to this initial plan. Campuses prepare LRDPs based on their academic goals and projected student enrollment levels. Each plan identifies how a campus will accommodate the anticipated enrollment along with the faculty and staff needed to support that enrollment. Thus, an LRDP also serves as an important policy document that outlines a campus�s priorities and guides future development. An LRDP requires approval by the UC Board of Regents.

Contains Four Major Elements. In order to assist campuses in developing an LRDP, the UCOP provides general guidelines regarding the organization and components to be included in such a plan. For example, an LRDP should generally show how and where space needs will be met on the campus site (such as the location and number of additional housing units). The plan should also contain the following four elements:

Land Use. The plan provides guidance for future structure placement and land use while maintaining adequate flexibility for future decision making. The level of detail in this element varies for by campus. For example, while UC Riverside�s LRDP specifies the location, type, and number of new student family housing units, UC Santa Cruz�s LRDP only indicates that phased redevelopment of existing student family housing units is projected and that additional units may be developed in other locations.

Landscape and Open Space. The plan also identifies areas of open space, which could include paved plazas, less formal landscaped areas, and undeveloped natural areas.

Circulation and Transportation. The plan shows how people move through the site and considers all forms of travel, including pedestrian, bicycle, mopeds, motorcycles, cars, service and delivery vehicles, and emergency vehicles. The plan also addresses parking for all vehicle types.

Utilities. The LRDP discusses how campus systems for irrigation water, waste water, storm drainage, sanitary sewers, chilled water and steam, electrical distribution, natural gas, and communications will accommodate the projected campus population.

Beyond these guidelines, the UCOP does not impose specific requirements for the content, organization, or longevity of an LRDP. Although the university�s guidelines state that campuses must consult with community groups and neighboring cities and counties when developing an LRDP, the guidelines do not specify the extent and timeline of the consultation process. As a result, the organization of an LRDP and the process used to develop it often varies across campuses. For example, a committee comprised of both campus and local government representatives oversaw the development of UC Santa Cruz�s most recent LRDP. In contrast, the LRDP committees at most other campuses typically do not include representatives from the surrounding cities and counties.

LRDP Facilitates UC Approval of Specific Campus Projects. While the state does not require campuses to develop LRDPs, UC Regents� policy is to require site-by-site project approval by the Regents for campuses that lack an LRDP. For campuses with an LRDP, the UC President (without needing the Regents� approval) can approve proposals for individual buildings if their locations are generally in accordance with campus LRDPs. Thus, it is advantageous for a campus to have an LRDP when obtaining systemwide approval for its capital outlay projects. As we discuss later in this report, existing state law does require the university to prepare and certify an Environmental Impact Report (EIR) for each LRDP. Since an LRDP covers a series of individual projects that will be carried out in phases, the accompanying EIR is commonly referred to as a �Master EIR.�

Not Subject to Local Land Use Control. As a state institution, UC is constitutionally exempt from local land use control. This means that the local government�s planning commission does not have the jurisdiction to reject or oppose a campus�s LRDP or a specific capital project. In contrast, a private company or institution-such as Stanford University-must abide by local land use regulations, submit its long range plan for review and approval by the local government, and pay for all costs related to its plan and projected campus growth (such as development impact fees). In addition, state agencies typically do not review or approve a UC campus�s LRDP. Currently, the Legislature does not provide any formal guidance or oversight regarding the development or implementation of an LRDP.

Although each LRDP has an established time horizon, it does not automatically expire at the end of that horizon. A campus�s plan remains in effect until the UC Regents approve an updated LRDP (with a new time horizon) for that campus. Under certain circumstances, a campus might not develop an update soon after the horizon year of the existing LRDP. This could be because the particular campus had not yet grown to the enrollment and development limits defined in the existing LRDP, due perhaps to lower enrollment demand or lack of funding for the specific capital outlay projects envisioned in the plan.

Figure�1 summarizes the status of each UC campus and medical center�s LRDP. Typically, if a medical center is located in close proximity to the main campus (such as in Los Angeles), a single LRDP covers both the campus and medical center. As indicated in the figure, UC campuses and medical centers are in various stages of updating their LRDPs. As a result, campuses tend to have different time horizon years based on their particular priorities and objectives. The entire LRDP process (from the time a campus begins to develop an LRDP to when it is approved by the Regents) typically takes two to three years.

|

Figure 1 University of California Long Range Development Plan (LRDP) Status |

||

|

Campus/Medical Center |

Approval Date |

Horizon Year |

|

Recently Updated LRDPs |

|

|

|

Berkeley |

January 2005 |

2020 |

|

Davis |

November 2003 |

2015 |

|

Irvine Medical Center |

January 2003 |

2020 |

|

Los Angelesa |

March 2003 |

2010 |

|

Merced |

January 2002 |

2015/2025b |

|

Riverside |

November 2005 |

2015 |

|

San Diego |

September 2004 |

2020 |

|

San Franciscoa |

January 1997 |

2011 |

|

Santa Cruz |

September 2006 |

2020 |

|

Developing Updated LRDPs |

|

|

|

Davis Medical Center |

2007c |

TBDd |

|

Irvine |

2007c |

TBD |

|

San Diego Medical Center |

TBD |

TBD |

|

Santa Barbara |

2007c |

2025 |

|

|

||

|

a All sites, including the medical center. |

||

|

b Phased development because Merced is a new campus. |

||

|

c Anticipated approval date. |

||

|

d To be determined. |

||

The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) requires that a comprehensive EIR be prepared specifically for the LRDP of a public higher education campus or medical center. (Please see nearby box for a more detailed description of CEQA.) The EIR essentially evaluates the impacts of the plan on the surrounding environment and considers ways to mitigate those impacts. Under CEQA, the Regents-as the �lead agency�-must certify an EIR before approving an LRDP. Since the LRDP includes multiple projects, the accompanying EIR is typically referred to as a �master� or �program-level� report (evaluating the overall impact of the plan) rather than a project-level report (evaluating each project separately). As each project covered by the LRDP begins implementation, CEQA requires that the university prepare a project-level EIR. However, given the certification of a program-level EIR on the entire LRDP, these project-level EIRs are not required to be as detailed as those for non-LRDP projects.

What Is the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA)?The CEQA was enacted in 1970 in order to ensure that state and local agencies consider the environmental impact of their decisions when approving a public or private project. Unlike many other environmental laws that are focused on an endangered species or a single medium (air, water, land), CEQA requires decision makers to consider a project�s impacts on all specified aspects of the environment before approving it. (In our 1997 report CEQA: Making It Work Better, we examined the entire CEQA process and made recommendations to make the process more efficient and therefore less costly and time consuming for both project developers and public agencies.) The main purposes of CEQA are to:

Currently, any project that may cause a significant physical change in the environment is subject to CEQA review. Projects include those carried out by public agencies themselves and private projects linked to a public decision-making process, such as permit approval or granting of public funds. Certain projects are fully or partially exempt from CEQA requirements either by state law or regulation adopted by the Secretary for Resources. Under CEQA, a �lead� public agency must first conduct a preliminary analysis to determine whether a project may have significant adverse environmental impacts. The lead agency is a public agency that is carrying out its own project, or, in the case of a private project, the public agency that has responsibility for overseeing or approving the project. Typically, the lead agency will be a city or county, or a state agency (such as the University of California). If the lead agency finds that a project will create possible significant impacts, then it is required to prepare an environmental impact report (EIR). The EIRs serve a number of functions. The analyses force agencies to (1) develop specific information about how projects may adversely affect the environment, (2) involve the public in environmental decision making, (3) facilitate interagency consultation, and (4) generate proposals for project modification to be achieved through the adoption of alternatives or mitigation measures. |

EIR Identifies Mitigation Measures. In developing an EIR, UC must follow the same requirements as other lead agencies (such as a city or county) for projects found to create possibly significant impacts on the environment. The EIR must (1) provide detailed information about a project�s likely effect on the environment, (2) identify measures to mitigate significant environmental effects (such as mitigating traffic impacts by constructing physical improvements like traffic signals or roundabouts), and (3) examine reasonable alternatives to the project. In addition, the EIR must consider a project�s significant �cumulative impacts�-that is, impacts over time and in conjunction with related impacts of other past, present, and future projects.

If an EIR finds that a project will have significant adverse environmental impacts (such as air pollution or increased traffic), UC is prohibited from approving the project unless it either makes (1) modifications that substantially lessen the adverse environmental effects or (2) finds that specific overriding economic, legal, social, technological, or other benefits of the project outweigh the environmental effects. In the latter case, UC may approve the project after making a �statement of overriding considerations,� which specifies the perceived benefits that project approval will create.

When adopting mitigation measures, UC must also develop a process for reporting the future implementation and results of such measures. The reporting or monitoring process must be designed to ensure compliance during project implementation. Under CEQA, UC-like other lead agencies-is responsible for implementing mitigation measures that are within its jurisdiction. As we discuss in a later section, if UC campuses identify off-campus mitigation measures (which are outside UC�s jurisdiction), they typically negotiate with local cities and counties regarding their implementation.

UC Regents Certify EIR. In developing an EIR, CEQA requires UC first to prepare a preliminary EIR for public review. The UC must provide public notice that it is preparing such a document and allow at least 30 days for public comment. The UC must evaluate all comments received during the public review period and prepare written responses to them, which must be included in the final EIR.

The CEQA also requires UC to consult with �responsible� state agencies which have a role in permitting a project. The law provides strict time limits for responsible agencies� review and comment. The California Coastal Commission and the California Department of Fish and Game frequently serve as responsible agencies for UC projects.

The UC�s long range planning process is similar to the process used by the state�s two other public higher education segments-the California State University (CSU) and the California Community Colleges (CCC). However, the process tends to be different for private colleges and universities in California, as well as some public universities in other states as discussed in more detail below.

CSU. Each of the 23 CSU campuses develops a physical master plan that guides the future development of campus facilities based on its academic priorities and student enrollment projections. The physical plan is not subject to local land use regulations and usually covers a time period of ten years. Faculty, staff, and students are often involved in the planning process. As with UC, CEQA requires CSU campuses to complete an EIR for each plan that identifies measures to mitigate environmental impacts. The CSU Board of Trustees serves as the lead agency in the EIR process and has sole jurisdiction in approving both the physical plan and EIR.

CCC. Each community college district maintains a district-wide master plan, as well as a separate master plan for each college located in the district. The master plan serves as a comprehensive planning document encompassing all functions of the college or district for a period usually of ten years. Moreover, it includes a facilities component that evaluates existing land, infrastructure, and facility needs, and specifies the capital outlay projects necessary to meet those needs. The various districts and colleges are exempt from local land use regulations. In accordance with CEQA, the district prepares an EIR that is subsequently reviewed and approved with the master plan by the district�s board of trustees.

Private Colleges and Universities in California. Unlike the state�s public higher education segments, private colleges and universities in California are subject to local land use regulations and seek approval of their long range plans (also referred to as general use plans or master plans) from local jurisdictions. For example, Stanford University�s physical development plan required the approval of the Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors. (Although the university as a whole falls into six public jurisdictions, the main academic area is in an unincorporated area of Santa Clara County.) In accordance with CEQA, the governing city or county also serves as the lead agency in the preparation and certification of the accompanying EIR.

Public Universities in Other States. In preparing this report, we interviewed officials from universities in others states regarding their development of long range physical plans. Specifically, we examined the processes at Arizona State University, University of Colorado, State University of New York, University of Texas, and the University of Washington (UW). Although the campuses of these universities have plans functionally similar to UC�s LRDPs, none expects to increase student enrollment as rapidly as UC�s campuses. Thus, the level of conflict with local communities regarding the long range plans is lower.

At almost every university campus we interviewed, plans are approved by the respective governing boards. The University of Colorado, however, must also seek the approval of the Colorado Commission on Higher Education (which is similar to the California Postsecondary Education Commission). Based on an agreement between UW and the City of Seattle, the university�s Seattle campus is required to have its master plan approved by the Seattle City Council. In terms of environmental regulations, only two of the states that we researched-Washington and New York-have environmental laws similar to CEQA that require them to disclose information to the public about significant environmental impacts and mitigate these impacts when possible.

An LRDP is essentially a campus�s plan for accommodating future growth, such as accommodating a projected increase in eligible students. However, some communities surrounding UC campuses have expressed concern about the impacts of planned enrollment growth. Specifically, they question (1) how much campuses should grow and (2) how much UC should pay for the impacts related to that growth. Below, we examine each of these issues.

Future student enrollment levels are the main drivers of a campus�s LRDP. For example, the number of new academic facilities and housing units depends upon how many additional students enroll at the campus. Thus, a campus will develop an LRDP by first projecting the number of additional students it plans to enroll in future years. For example, UC Riverside�s current LRDP, which was approved by the Regents in November 2005, assumes that enrollment on the campus will reach�25,000 students by 2015-16. This is a total increase of about 8,600 students (or 50�percent) above the campus�s 2004-05 enrollment level. This reflects an average annual increase of about 3.9�percent. As we discuss below, such enrollment projections are based on anticipated changes in the state�s demographics, as well as policy choices based on academic goals and priorities.

Unlike enrollment in compulsory programs such as elementary and secondary schools, which corresponds almost exclusively with changes in the school-age population, enrollment in higher education responds to a variety of factors. Some of these factors, such as population growth, are largely beyond the control of the state. Others, such as the creation of new graduate education programs, stem directly from policy choices. In general, enrollment growth corresponds to (1) growth in the college-eligible population and (2) changes in participation rates.

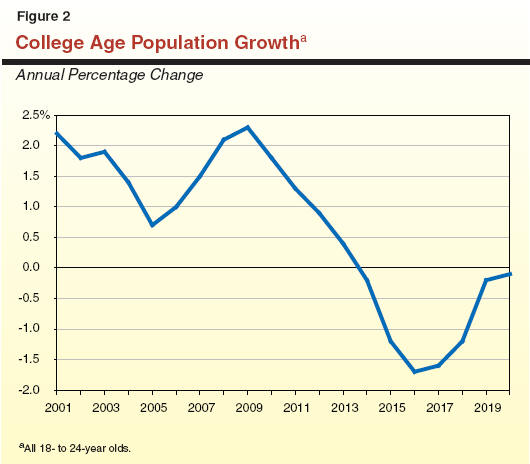

Demographics-Population Growth. Other things being equal, an increase in the state�s college-age population causes a proportionate increase in those who are eligible to attend each higher education segment. Population growth, therefore, is a major factor driving increases in college enrollment. Enrollment projections, particularly for UC, are heavily affected by estimates of growth in the college-age �pool� (18- to 24-year old population). This population has grown modestly in recent years (see Figure�2). Annual growth rates will peak around 2009, and will slow thereafter. In fact, between 2014 and 2020, the state�s college-age population is expected to shrink. This downward trend reflects an anticipated reduction in the number of California public high school graduates.

Policy Choices and Priorities-Participation Rates. For any subgroup of the general population, the percentage of individuals who are enrolled in college is that subgroup�s college participation rate. California�s participation rates are among the highest in the nation. For example, California ranks fifth in college enrollment among 18- to 24-year olds. However, projecting future participation rates is difficult because students� interest in attending college could be influenced by a number of factors (including student fee levels, availability of financial aid, and the availability and attractiveness of employment options). In addition, state actions taken to increase the number of students enrolled in a particular program (such as nursing or teacher credentialing) would increase overall participation rates as would expansion of various graduate or professional school programs. (Please see our previous report, Funding Enrollment Growth at UC and CSU, for more detailed information about the factors that influence enrollment growth and the cost to serve additional students.)

In 1999, the UCOP independently developed systemwide enrollment projections through 2010-11 to help guide the university�s academic planning efforts. A combination of demographic growth and program expansions, these projections reflect UC�s own long-term vision and goals. The actual enrollment at UC requires particular levels of funding from the Legislature, which may have different priorities. In other words, the Legislature may fund a different level of enrollment growth than UC requests.

The university�s 1999 enrollment projections (which exclude health science students) assume that the percentage of recent California high school graduates enrolled at UC will generally remain constant throughout the forecast period. However, the projections also assume that the percentage of adults participating in graduate education programs will increase enough to fulfill the university�s planned expansion of existing and new graduate programs, particularly at the professional-school level.

Figure�3 summarizes UC�s current long-term enrollment projections that were initially developed in 1999 and subsequently revised to include newly funded summer students. As we discuss below, the state has provided supplemental funding in recent years to support existing summer students at particular campuses.

|

Figure 3 UC Long-Term Enrollment Projectionsa |

||||

|

(Full-Time Equivalent Students) |

||||

|

|

|

|

Change |

|

|

|

1998-99 |

2010-11 |

Amount |

Percent |

|

Berkeley |

27,800 |

33,170 |

5,370 |

19% |

|

Davis |

20,300 |

28,500 |

8,200 |

40 |

|

Irvine |

15,700 |

28,540 |

12,840 |

82 |

|

Los Angeles |

28,500 |

34,110 |

5,610 |

20 |

|

Mercedb |

� |

5,000 |

5,000 |

� |

|

Riverside |

9,550 |

20,320 |

10,770 |

113 |

|

San Diego |

16,850 |

28,365 |

11,515 |

68 |

|

Santa Barbara |

17,880 |

22,685 |

4,805 |

27 |

|

Santa Cruz |

10,420 |

17,215 |

6,795 |

65 |

|

Totals |

147,000 |

217,905 |

70,905 |

48% |

|

|

||||

|

a Initially developed in 1999 and revised in 2002 and 2004 to include state supported summer students. Does not include health science students. |

||||

|

b The Merced campus did not open until fall 2005. |

||||

As shown in the figure, UC�s plan is that systemwide enrollment-excluding health science students-will increase by 48�percent (or roughly 71,000 additional full-time equivalent [FTE] students) during the seven-year period from 1998-99 to 2010-11. Based on these systemwide projections, each campus is assigned a long-range enrollment projection that forms the basis of its LRDP. Figure�3 shows the enrollment projections for each campus. For example, the Irvine campus is projected to increase enrollment by about 80�percent (almost 13,000 students) from its 1998-99 level.

Campuses Sometimes Make Own Enrollment Projections. Many of the recently approved campus LRDPs are based on a time horizon that goes beyond the 2010-11 time horizon of the 1999 enrollment plan. For example, UC Riverside�s current LRDP is based on enrollment projections through 2015. For those years after 2010-11, an individual campus-in consultation with the UCOP-essentially projects its enrollment based on its own priorities. In other words, the university currently has not made systemwide enrollment projections beyond 2010-11.

UC Intends to Develop New Enrollment Plan. According to the UCOP, the university has initiated a process for developing enrollment projections to at least 2015-16, including both general campus and health sciences. This process will include a review of state demographics and program needs, and individual campus growth proposals. The university anticipates that a new enrollment plan will be finalized during the 2007-08 academic year. The UCOP states that the UC Regents do not approve systemwide enrollment plans.

Student enrollment increases do not necessarily require a commensurate expansion of facilities. This is because campuses may have unused capacity that could accommodate additional students. For example, operating higher education campuses on a year-round schedule-which more fully utilizes the summer term-is an efficient strategy for serving more students with existing facilities. Such strategies have the benefit of significantly increasing UC�s enrollment capacity while reducing out-year costs associated with constructing new classrooms.

Summer Enrollment Not at Full Capacity. Accordingly, the Legislature has encouraged both UC and CSU to serve more students during the summer, in part by providing supplemental funding to enhance summer operations at specific campuses. In recent years, summer enrollment has increased. For example, between summer 2000 and summer 2005, summer enrollment at UC campuses almost doubled. However, despite this increase, the summer term at UC still serves only a fraction of the fall enrollment level. Figure�4 compares the number of FTE students served in summer 2005 with the number served in fall 2005. As shown in the figure, the summer term at UC serves one-fifth the number of students as the fall term. In other words, UC�s campuses operate in summer at only 20�percent of their fall levels. Thus, UC could serve tens of thousands of additional FTE students without necessarily expanding its physical development. (Please see our Analysis of the 2006-07 Budget Bill for a more detailed update on year-round operations.)

|

Figure 4 University of California Percentage of Students Served in Summer Versus Fall |

|||

|

|

Summer 2005 FTEa Students |

Fall 2005 FTE Students |

Summer as Percent of Fall |

|

Berkeley |

3,900 |

30,924 |

13% |

|

Davis |

5,805 |

25,765 |

23 |

|

Irvine |

4,425 |

22,974 |

19 |

|

Los Angeles |

7,500 |

31,306 |

24 |

|

Riverside |

2,769 |

15,547 |

18 |

|

San Diego |

3,735 |

23,821 |

16 |

|

Santa Barbara |

6,150 |

20,105 |

31 |

|

Santa Cruz |

2,052 |

14,960 |

14 |

|

Totals |

36,336 |

185,402 |

20% |

|

|

|||

|

a Full-time equivalent. |

|||

When a campus�s enrollment and facilities expand, it can sometimes negatively affect the surrounding environment (such as through increased pollution or traffic). Under CEQA, the campus is required to identify and implement measures to mitigate such adverse impacts. As mentioned earlier in this report, campuses and their surrounding communities sometimes disagree about the responsibility for impacts occurring outside of the university�s jurisdiction. For example, although a new signal light in the city could manage traffic from a campus expansion, the city and campus might disagree about how the cost of that signal light should be shared.

Current UC policy asks campuses to voluntary negotiate in �good faith� with local governments regarding a monetary contribution to mitigate off-campus impacts. According to the policy, these negotiations should be similar to the process for determining capital fees for public utility facilities. (Existing law requires UC to negotiate with public utility providers for payment of capital facility fees. Please see box for more information about this process.) The university requires that campuses make an effort to pay for their fair share of the identified impacts. This could result in noncampus entities (such as private developers) contributing to a particular impact. For example, if the campus is responsible for 80�percent of the traffic on a particular street, then it may decide to contribute 80�percent of the cost for a new traffic signal.

Capital Facility Fees Paid to Public Utility AgenciesExisting state law (Government Code Section 54999) authorizes public agencies that provide utility services-including local publicly owned electric utilities-to impose capital facility fees on school districts, county offices of education, community college districts, California State University campuses, University of California campuses, and state agencies that receive such services. (A capital facility fee refers to a nondiscriminatory charge-meaning it does not exceed the amount charged to nonpublic users and does not exceed the proportionate share of usage-to pay the capital cost of a public utility.) Public agency utilities must negotiate with these entities regarding the specific fees and show that the fee is in fact nondiscriminatory. |

Under the university�s policy, however, a UC campus will only pay its fair share if the responsible jurisdiction (such as the city or county) has (1) established and implemented an appropriate mechanism for identifying and collecting fair share payments from UC and any other developers that contribute to the identified impacts, (2) built the identified improvements, and (3) reached an agreement with UC on a �trigger� point (such as an off-campus intersection reaching a certain level of congestion) when UC will contribute its fair share payment. This means that the responsible jurisdiction must first pay the upfront costs of any such improvements.

No UC Campus Has Reached a Fair Share Agreement. As previously mentioned, each EIR that accompanies an LRDP identifies off-campus impacts. Environmental Impact Reports developed after 2002-when UC initially developed its fair share policy-typically include a general statement that the campus will work with the appropriate jurisdiction and contribute its fair share of the improvements needed to mitigate the identified impacts. However, the EIR generally does not define UC�s fair share contribution and does not include a time frame in which UC would make any such payments. According to UC, a campus would negotiate with a local agency a separate fair share agreement for each impact. At the time this report was being prepared, no UC campus had reached a fair share agreement with a neighboring jurisdiction regarding a particular mitigation measure identified in an EIR associated with an LRDP. This means no UC campus has paid its fair share for identified off-campus mitigation measures.

As we discuss below, a recent court case involving CSU increases the need for California�s public universities to work with local municipalities in paying their fair share of off-campus impacts.

In 1994, CSU agreed to establish a Monterey campus on a portion of the former Fort Ord military base as part of the Fort Ord Reuse Authority (FORA) Act. (The state Legislature created FORA-which includes Monterey County and the Cities of Monterey, Salinas, Carmel, Marina, and Pacific Grove-to manage the transition of the base from military to civilian use.) The CSU Board of Trustees in 1998 certified a master plan for the new campus and an accompanying EIR, which identified significant environmental impacts to various public resources. The Trustees agreed to mitigate those impacts that would occur on campus. However, they determined that the mitigation of off-campus impacts-including increased traffic and a greater demand for fire protection services-was not within their jurisdiction, but rather within the jurisdiction of FORA. Accordingly, the Trustees declined to fund off-campus mitigation measures. They also claimed that contributing funds to FORA was legally infeasible and that overriding social, cultural, and economic reasons supported approval of the project despite its significant effects on the environment.

In response, FORA and the City of Marina challenged the Trustees� decision to certify the EIR despite the unmitigated effects as a violation of CEQA. In July 2006, the California Supreme Court reversed an earlier Court of Appeal�s decision by concluding that the Trustees had abused their discretion and thus their approval of the EIR was not valid. The court concluded that �an EIR that incorrectly disclaims the power and duty to mitigate identified environmental effects based on erroneous legal assumptions is not sufficient as an informative document.� Specifically, the Supreme Court ruled that:

Off-Campus Impacts Must Be Mitigated. The CEQA does not limit the CSU Trustees� obligation to mitigate or avoid significant environmental effects occurring only on the university�s own property. Rather, they are required to mitigate a project�s significant effects on the environment.

Voluntary Payments Are a Feasible Form of Mitigation. If the Trustees cannot adequately mitigate off-campus environmental effects with actions on campus, then to voluntarily pay a third party (such as FORA) to perform the necessary acts off campus is a feasible form of mitigation. Such a payment is not a gift of public funds because �while education may be CSU�s core function, to avoid or mitigate the environmental effects of its projects is also one of CSU�s functions.� The university has an obligation to negotiate with local public agencies its fair share of the environmental impacts.

Unlike UC, private colleges and universities in California (such as Stanford University) are required to pay development impact fees to mitigate all environmental impacts related to their growth-both on and off campus. In terms of other states, none of the universities we examined have polices that require them to compensate local public agencies for the impacts of campus growth. There are also no laws or court decisions in those states that require them to pay for the mitigation of environmental impacts. However, some universities, like Arizona State University, occasionally offer to help pay for the mitigation of off-campus impacts. As mentioned earlier in this report, the universities that we reviewed in other states are not expanding student enrollment as rapidly as UC and CSU.

In our review of the process used by UC to prepare and implement LRDPs (as well as the accompanying EIRs) for its campuses and medical centers, we generally found a lack of accountability, standardization, and clarity. This unnecessarily creates tension between the university and local communities regarding how much campuses should grow and the mitigation of the environmental impacts related to that growth. Figure�5 summarizes our major findings, which we discuss in further detail below.

|

Figure 5 Summary of Major LAO Findings |

|

|

|

� Lack of State Accountability and Oversight. Generally, the state neither approves a Long Range Development Plan (LRDP) nor monitors the implementation of the mitigation measures identified in the accompanying Environmental Impact Report (EIR). |

|

� Lack of Standardization in Public Participation. The University of California (UC) Office of the President does not provide campuses with specific requirements for how local communities should be involved in the LRDP process. As a result, the degree to which local communities are involved in the planning process can vary across campuses. |

|

� Minimal Systemwide Coordination in Projecting Enrollment for Recent LRDPs. In 1999, UC developed systemwide enrollment projections through 2010-11, which were used to develop an enrollment plan for each campus. However, when a campus prepares an LRDP that goes beyond 2010-11, it independently develops its own enrollment projections for those subsequent years. |

|

� Campuses Want to Primarily Expand Graduate Enrollment. Much of the projected enrollment growth at UC will not be due to increases in freshman enrollment, but rather because of a desire to expand and create new graduate programs (such as in law and public policy). This is because the number of California public high school graduates is expected to decline. |

|

� Lack of Clarity in California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). The CEQA process can often be costly and time consuming for both the public and private sectors. In part, this is because there are a number of provisions in CEQA where definitions and requirements are unclear or imprecise. |

|

� No UC Campus Has Reached a �Fair Share� Agreement. Although UC has a policy for campuses to work with local public agencies to contribute its fair share payments to mitigate off-campus impacts, no UC campus has been able to reach such an agreement with a neighboring jurisdiction. |

As mentioned above, UC-as a state agency-is constitutionally exempt from local land use regulations. Unlike the case with private developers and universities, the local government�s planning commission does not have any jurisdiction over a UC LRDP. As a result, the university serves as its own lead agency in its LRDP and environmental review process. No other state agency approves an LRDP, unless it serves as a responsible agency (such as the California Coastal Commission) for environmental compliance. Moreover, the state does not review or monitor UC�s implementation of the LRDP and the mitigation measures identified in the accompanying EIR. As a result, there is very little state oversight of the LRDP process and the actual plan, and there is no process for ensuring that UC mitigates significant environmental impacts resulting from campus growth.

Although the Legislature considers funding requests for individual capital outlay projects as part of the state�s annual budget process, it does not directly review LRDPs to determine whether they are aligned to its fiscal and policy priorities from a statewide perspective. This is particularly important given that an LRDP serves as an important policy document that outlines the enrollment and academic goals of a UC campus and lays out the framework and rationale for future capital projects.

Although UCOP assists campuses during the LRDP process, it does not have specific requirements regarding what shall be included in the process. Therefore, there is often a lack of standardization in the degree to which local communities are involved in the planning process. For example, while some campuses developed an LRDP committee that included community representatives and local government officials (such as UC Santa Cruz and UC Riverside), other campuses (such as UC Davis) did not.

We also found that the number of public workshops held during the LRDP process can vary across campuses. (Although CEQA has specific requirements regarding public participation in the environmental review process, the university does not have specific requirements for public participation in the development of an LRDP.) In the process of updating their respective LRDPs, the Davis campus held 17 public workshops and the Santa Cruz campus held 5 public workshops. These public workshops generally allow a campus to inform the local community on its development of an updated LRDP—such as the different land use options that the campus is considering—and to solicit their feedback. Unlike most other campuses, however, UC Davis used the first few public workshops to solicit ideas from the community on how to develop certain areas of the campus prior to developing and presenting its own ideas to the community. The intent of the Davis campus was to involve the local community in the beginning of the planning process, rather than simply have the community react to the campus�s own proposals.

As discussed earlier, the university�s most recent plan for systemwide enrollment was developed in 1999, which projected student enrollment levels through 2010-11. However, some campuses have recently updated their LRDP based on a time horizon beyond 2010-11. For those years after 2010-11, an individual campus-in consultation with the UCOP-essentially develops its enrollment projections based on its own local priorities (such as academic goals and locally determined demographic trends) rather than systemwide needs. As a result, the campus�s post-2010-11 enrollment projections are not coordinated with the other campuses. This is particularly important given that the Master Plan provides admissions and enrollment guidelines on a statewide basis. For example, the Master Plan calls for UC (as a whole) to draw its students from the top 12.5�percent of public high school graduates in the entire state (not a particular region).

Campuses generally acknowledge that undergraduate enrollment demand will level out in a few years because of an anticipated reduction in the number of California high school graduates. According to the Department of Finance�s Demographic Research Unit, growth in the number of high school graduates in the state will peak in a couple of years, and then rapidly decline to the point of going negative in 2012-13. Much of the projected growth identified in recent LRDPs is based on campus desires to expand and create new graduate and professional school programs. For example, the Santa Cruz campus is considering creating professional schools in the areas of management, education, public policy, and public media. Similarly, UC Riverside�s LRDP provides a framework for establishing a new professional school in law or public policy.

In general, LRDPs do not explain the rationale for the proposed professional school from a statewide perspective and why it must be established at that particular campus (versus establishing it at another UC campus or expanding an existing program at another campus).

As we discussed in our 1997 CEQA report, the CEQA process can often be costly and time-consuming for project developers and public agencies. In part, this is because there are a number of provisions in CEQA where definitions and requirements are unclear, and thus subject to conflicting interpretations. For example, an EIR must include an analysis of the environmental impact for a range of reasonable project alternatives. However, the CEQA statute provides few guidelines as to the kinds of alternatives that must be considered and the level of detail required for each alternative. This has led to analyses of alternatives that contribute little to the decision making of public agencies. For instance, an alternative examined may not be feasible, such as the case where the alternative considered is development on a site not owned (or that cannot practically be purchased) by the developer. Other alternatives may focus mainly on differences in a project�s scale, rather than on more substantial differences in a project�s design.

As previously mentioned, an EIR is required (including the identification of mitigation measures) when a lead agency finds that a project may have �significant� adverse environmental impacts. While the CEQA guidelines provide some guidance as to the circumstances under which a project would normally have a significant effect on the environment, we found that more detailed guidance is needed to provide greater certainty in the application of this concept. In view of the above, several host communities have filed lawsuits claiming that certain campuses have not adequately analyzed all possible alternatives or clarified all mitigation measures. For example, a neighborhood group in West Davis argued that the Davis campus violated CEQA by not considering reasonable alternatives to a proposed housing project.

The UC�s policy calls for payment of its fair share of costs to implement mitigation measures for off-campus impacts. However, the university will do so only if the responsible jurisdiction implements a mechanism for identifying and collecting such payments, builds the improvement, and agrees with UC on a trigger point for when payments will need to be contributed. Local government officials argue that it is difficult for cities and counties to pay the upfront costs of certain mitigation measures.

As discussed earlier, currently no UC campus has made a payment to another public agency based on a fair share agreement regarding a mitigation measure identified in an EIR. For example, although the Davis campus is in the process of beginning some of the development projects outlined in its 2003 LRDP, it still has not reached an agreement with the City of Davis for its fair share payments (such as for fire services).

In this report, we have reviewed UC�s process for developing, approving, and implementing LRDPs for its campuses and medical centers. This review included an examination of the rationale for why campuses plan to increase enrollment and the responsibility of mitigating off-campus environmental impacts. We have also identified a number of important policy issues that merit legislative consideration. Based on our review and findings, we recommend (1) increasing legislative oversight over UC�s LRDPs, (2) developing a more standard approach for soliciting public input, (3) projecting enrollment growth based on statewide goals, (4) making better use of the summer term, (5) clarifying and improving CEQA, and (6) requiring a report on UC�s efforts to reach fair share agreements with neighboring jurisdictions.

We recommend greater legislative oversight over UC�s LRDPs, in order to ensure that campuses� long-term goals are aligned with statewide priorities. Specifically, we recommend UC provide copies of draft LRDPs to the Legislature as they are made available for public review.

Given that an LRDP plans for the accommodation of long-term enrollment and academic goals, we recommend greater legislative oversight over the development of UC�s LRDPs. Specifically, we recommend UC provide the Legislature with copies of draft LRDPs that are submitted for public review. (Before the UC Regents can approve an LRDP and accompanying EIR, a campus must allow time for the public to review and comment on these documents.) At its discretion, the Legislature could hold hearings to review certain aspects of these draft plans. Moreover, the Legislature could express any concerns about the draft LRDP before it became final. (This, however, would not preclude the Legislature from expressing concerns in the future when the university requests funding for specific projects related to the LRDP.)

As previously mentioned, the Irvine campus is currently in the process of updating its LRDP. Under our proposal, the Legislature would have an opportunity to review the rationale of a draft of the plan before it is voted on by the Regents (which is expected to be in 2007). This process would allow the university to amend the plan as needed to accommodate any legislative concerns.

Some relevant issues that the Legislature could examine in its review are:

How much is the campus or medical center projected to grow and what type of growth is anticipated (such as in new or expanded graduate and professional school programs)?

What is the rationale for the expected growth? How did the campus or medical center project the anticipated level of growth? Could the additional students be accommodated through better use of the summer term?

To what extent were local communities involved in the development of the draft LRDP?

What significant environmental impacts (if any) will the plan have on nonuniversity property? How does the university plan to mitigate such impacts?

We believe that legislative oversight would help ensure that the university�s long-term goals are aligned with the state�s priorities.

We recommend UC provide campuses and medical centers with more specific requirements regarding the level of public involvement in the LRDP process, in order to increase the transparency of the process.

As noted earlier, there is a lack of standardization across UC campuses regarding the degree to which local communities are involved in the LRDP process. This can sometimes make it difficult for certain communities to provide input in the development of a campus�s LRDP. For example, some of the residents we met with in Santa Cruz spoke about the lack of responsiveness by the campus to their concerns. Accordingly, we recommend UC provide more specific requirements and guidance to campuses developing LRDPs. For example, the university could require that a certain number of public workshops be held before the Board of Regents reviews a final LRDP. Moreover, UC could require that prior to developing the LRDP, each campus or medical center hold a series of public meetings regarding its academic and enrollment goals. Such an approach could increase the relevance of public input in the LRDP decision-making process. Finally, the university could require that each LRDP planning committee include a certain number of community representatives and local government officials.

We recommend the Legislature require UC to use systemwide enrollment projections to determine the enrollment levels assumed in each LRDP.

We recommend the Legislature require that the enrollment projections outlined in each LRDP be based on a systemwide enrollment plan, rather than the independent projections of an individual campus. In other words, in any given year the sum of the campus enrollment targets should equal the enrollment target for the entire university system (which in turn should be based on statewide goals and priorities). As noted earlier, UC is currently in the process of developing a new enrollment plan. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature direct UC to provide systemwide enrollment projections through 2020 at budget hearings this spring. In order for the plan to be a useful planning tool for the Legislature, we believe that it is important for the university to explain and justify the assumptions and data used to calculate the enrollment projections.

A systemwide enrollment plan would also assist the Legislature in assessing proposals to fund specific levels of enrollment growth (or additional students) at UC as part of the annual state budget process. For example, the Legislature may take issue with parts of UC�s enrollment plans and instead find that growth is needed in different programs in order to meet the state�s research and workforce needs (such as nursing), rather than in areas identified by UC. For example, at its November 2006 meeting, the UC Regents approved the development of a medical school at UC Riverside and a law school at UC Irvine. These plans may not be aligned with legislative priorities, given limited resources.

We recommend UC campuses make better use of the summer term as a means to accommodate an anticipated increase in the number of students without having to construct new classrooms.

Given the large unused capacity at UC during the summer term, we believe the Legislature and the university should continue to explore ways to increase enrollment during the summer term. This is because better utilization of the summer term is a more cost-effective strategy for accommodating new enrollment growth than building new facilities. In addition, such a strategy helps reduce the significant environmental impacts associated with the construction of facilities.

Below, we discuss steps that campuses could take to increase summer enrollments.

Offer Financial Incentives. Financial incentives can encourage students to enroll in the summer term. For example, campuses could charge lower fees for the summer term, which could be offset by somewhat higher fees for the other terms. In addition, campuses could offer fee rebates to seniors who graduate at the end of the summer rather than retuning in the fall.

Require Some Summer Enrollment at High-Demand Campuses. As we discussed most recently in our report, Promoting Access to Higher Education: A Review of the State�s Transfer Process (January 2006), some campuses do not have the capacity and resources to admit all eligible applicants that apply to them. If such high-demand campuses required students to attend some summer terms, they could accommodate more students.

Increase Access to High-Demand Courses. According to UC, the primary reason why many students enroll in summer courses is to complete required courses that they were unable to enroll in during the fall, winter, or spring term due to limited space. Campuses should view the summer term as an opportunity to offer courses that typically fill up quickly during the other academic terms. Increasing access in this way can ensure graduation in four years and potentially reduce time to degree.

We recommend the Legislature improve CEQA by clarifying language, improving definitions, and providing better guidelines on what constitutes feasible mitigation measures and alternatives.

As concluded above, CEQA currently provides lead agencies (such as UC) considerable discretion in the EIR process when it fails to provide clear definitions and requirements. For example, the act does not specify the kinds of alternatives that must be considered and the level of detail required for each alternative. Consequently, we recommend the Legislature clarify the terms and requirements of CEQA. For example, we recommend clarifying the scope of the alternative analyses in EIRs, including the reasonable number of alternatives to be considered and the level of detail in the analysis. We also recommend the Legislature provide better guidelines on what constitutes a significant environmental impact and a feasible mitigation measure. (We originally made these recommendations-along with many others-in our 1997 CEQA report in order to make the CEQA process less costly and time-consuming to project developers and public agencies.) Such clarification would help ease some of the tension between UC campuses and their surrounding communities.

In view of the recent court decision in City of Marina v. CSU Board of Trustees, we recommend UC report to the Legislature on what steps it will take to reach agreements with local public agencies regarding the mitigation of its fair share of environmental impacts.

As discussed in this report, the most contentious issue between campuses and their surrounding communities concerns the mitigation of off-campus impacts. Although UC agrees to work with communities in reaching an agreement for paying its fair share contribution, no campus currently has such an agreement in place. In view of the recent court decision in City of Marina v. CSU Board of Trustees, however, the university has an obligation to negotiate with local public agencies regarding the mitigation of its fair share of environmental impacts. Thus, we recommend the Legislature require UC to report on what additional steps it will take, including changes to the current three-step policy, to ensure that fair share agreements are in fact developed with the appropriate jurisdictions. We believe that it is important for the Legislature to have assurance that there is resolution on the mitigation of off-campus impacts prior to considering related UC capital outlay projects. Depending on the outcome of UC�s report, the Legislature could decide not to approve funding for a UC capital outlay project until the appropriate campus has entered into a memorandum of understanding with the appropriate jurisdictions regarding the mitigation of off-campus impacts associated with that project.

In summary, our proposed recommendations would improve the transparency and accountability of UC�s LRDP process. For example, we propose steps that require the university to justify the rationale behind its long-term enrollment and academic plans. Our proposals attempt to ensure greater legislative oversight and public involvement in the development of an LRDP. In addition, our proposals help address the fundamental conflicts of how much should campuses grow (including whether such growth could be accommodated with existing facilities) and who should pay for the mitigation of environmental impacts related to that growth.

|

Acknowledgments This report was prepared by Anthony Simbol with assistance from Minsun Park, and reviewed by Steve Boilard. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail subscription service , are available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814. |