April 2006

The state has long recognized its responsibility to protect the general health and safety of the people of California. To protect Californians from hazards posed by waste facilities and surface mines, the state�s environmental regulatory agencies require financial assurances from the owners/operators of these facilities-evidence that these parties have the financial capacity to restore public resources that they degrade. This report details California�s existing financial assurance requirements, examines shortcomings with the current financial assurance system, and recommends improvements. Adoption of our recommendations should decrease the likelihood that financial assurances will fail to serve their public purpose, thereby reducing the state�s exposure to significant financial risk in the future.

The government has long recognized its responsibility to protect the general health and safety of the people of the state. Some forms of protection are obvious, such as fire and police protection. Other forms are less well known, including the state�s role to protect citizens from hazards posed by waste facilities and surface mines. Recently, for example, the state assumed responsibility for the maintenance of a hazardous waste landfill in southern California (see box below). It did so in order to protect the public from dangerous gas leaks that would occur if maintenance activities ceased. This report focuses on one aspect of state efforts to provide public protection from waste facilities and surface mines. This effort is referred to as financial assurances.

Financial Assurances. Financial assurances are evidence provided to the state by operators of waste facilities and surface mines that they have the financial capacity to restore public resources that they degrade. Such restorations are intended to ensure that a site does not pose a health or safety threat to the public. The concept of financial assurances is based on the �polluter pays� principle which argues that individuals or businesses who use or degrade a public resource (such as land or water) should pay all or a portion of the costs imposed on the public by their use of the resource.

There are two broad categories of financial assurances: those required while the facility is operational and those required once a facility ceases operation (through closure or abandonment). This report focuses on the second category of financial assurances-that is, those for �nonoperational� activities. Generally, we found that financial assurances for facilities when in operation are not a concern. This is because when a facility is in operation, the owner/operator typically has a source of revenue generated from the facility (such as from landfill disposal charges or the sale of mined materials) that can be used to address pollution problems. Additionally, the owner/operator has an incentive to mitigate a pollution problem at a facility in order to maintain its environmental permit status that enables the facility to operate and generate revenue.

As regards closed facilities, we found that financial assurances do not account for all of the costs associated with ensuring that a site does not pose a threat to the public or the environment. Consequently, instead of the owner/operator paying the full cost of cleaning up and maintaining the site, consistent with the polluter pays principle, the state will likely bear part or all of the burden. The California Integrated Waste Management Board (CIWMB), for example, estimates that the state could face a $1.8 billion risk for the ongoing maintenance of closed solid waste landfills by mid-century. We believe that if the Legislature addresses problems with financial assurance requirements now, the state will reduce its risk of being potentially exposed to billions of dollars in costs needed to maintain waste facilities and surface mines in the future.

In the first section of this report, we compare and contrast financial assurance policies at various state agencies. Next, we discuss issues for legislative consideration and make recommendations on how to improve financial assurance policies and practices so as to minimize the state�s potential future-year costs.

Methodology. In reviewing the financial assurance policies and practices, we interviewed a broad range of interested parties, including staff of a number of state resources and environmental protection agencies and representatives from the financial, insurance, waste, and surface mine industries. We also reviewed documents from state resources and environmental protection agencies, the United States Government Accountability Office, and individual case studies. We also participated in workshops with state agencies, industry, and environmentalists.

The BKK Landfill- Private Failure, Public CostsFor nearly 20 years, the BKK landfill site accumulated hazardous and solid waste. Located in a mixed residential/industrial neighborhood of the southern California city of West Covina, the boundary of the 583-acre BKK landfill lies, at some points, just 25 feet away from nearby homes. Between 1972 and 1984, BKK collected, on one 190-acre section of the landfill, 3.4 million tons of hazardous waste. The BKK Corporation began closure activities at the 190-acre parcel in the late 1980s. In 1991, the Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC) certified that section of the landfill�s closure, which included a five-foot thick clay cap, vegetative cover, a gas collection system, and a leachate treatment plant. State regulation required the BKK Corporation to maintain the toxic waste site for at least 30 years after its closure to ensure that the site did not pose a public health or safety threat. The BKK Corporation obtained an insurance policy worth over $37 million to serve as the corporation�s �financial assurance� to the state that it had the financial capacity to adequately maintain the site after its closure. Throughout the 1990s, the BKK Corporation reported financial troubles, troubles that it would ultimately transfer to the City of West Covina and to the state. Specifically, in October of 2003, the corporation failed to pay its remaining insurance premiums on the BKK site. The City of West Covina paid the premiums, thereby stabilizing the site�s insurance funds. Then, in October of the following year, the BKK Corporation informed DTSC that it would no longer conduct postclosure maintenance at the hazardous waste site, maintenance necessary to prevent the release of hazardous substances into the air and water. In November 2004, to protect the public health and safety, DTSC assumed responsibility for maintenance of the BKK hazardous waste site. This is the only time in the department�s history it has initiated such an emergency response. The DTSC has contracted with Engineering/Remediation Resources Group, Inc., an organization experienced in postclosure management of waste facilities, for continued maintenance of the BKK site. The department is seeking reimbursement for maintenance costs that it has assumed from the BKK Corporation and from parties that disposed of hazardous waste at the site and therefore may share the legal responsibility to pay for the site�s cleanup and maintenance. These �responsible parties� include both private and public organizations, a number of state entities among them. To date, the state has spent over $14 million from the General Fund to maintain the BKK site, while it has recovered about $6 million from responsible parties to offset these costs. Future state costs to maintain the BKK landfill are difficult to project; however, the current budget includes $8.5 million from the General Fund ($5.5 million ongoing) to maintain the hazardous waste site. Preservation of public health and safety will likely require maintenance at the BKK site for many years to come. |

What Are Financial Assurances? Financial assurances are evidence to the state that the owner or operator of a waste site or surface mine has the financial resources to restore the site to a condition that poses no threat to public safety, public health, or the environment. Waste sites include solid waste or hazardous waste disposal facilities and hazardous waste treatment, transfer, or storage facilities. In general, solid waste is garbage, refuse, sludge, and other discarded solid materials resulting from residential activities and industrial and commercial operations. In comparison, hazardous waste is waste that is toxic, ignitable, reactive, or corrosive. (Waste sites and surface mines are the only facilities regulated by departments under the Resources Agency and California Environmental Protection Agency [Cal-EPA] that require financial assurances.) This evidence can take many forms, such as a trust fund, insurance policy, letter of credit, or surety bond. We discuss these in detail later. Most financial assurances are required upfront, that is, before an entity can commence operations under the environmental regulatory permit.

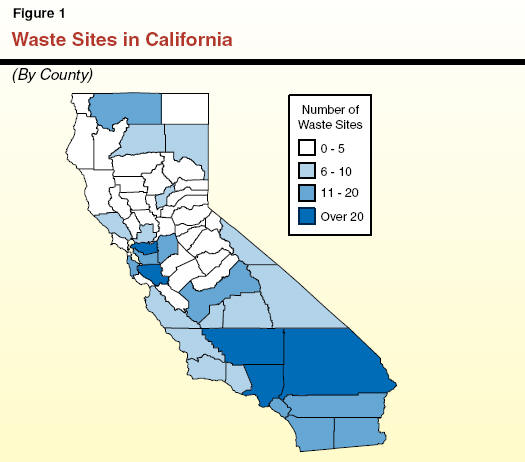

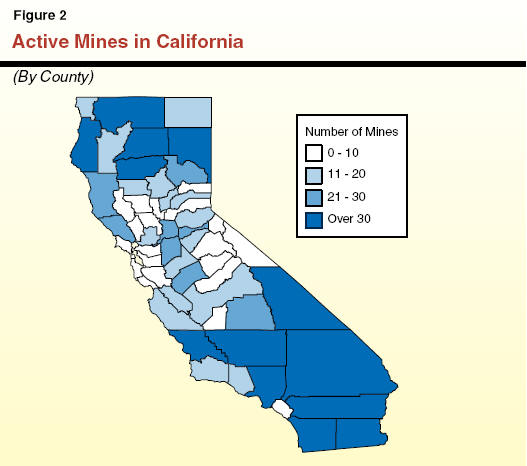

Where are Facilities Requiring Financial Assurances Located? As previously mentioned, financial assurances are required for waste sites and surface mines. These facilities are located throughout the state. As shown in Figures 1 and 2, waste facilities and surface mines are located in every county in the state. Of the waste facilities, however, hazardous waste facilities are mostly located in the San Francisco Bay, Sacramento, and Los Angeles areas, while solid waste facilities are located in almost every county.

Multiple State Agencies Require Financial Assurances. Figure 3 shows the four state regulatory agencies that require financial assurances: the Department of Conservation (DOC), the CIWMB, the Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC), and the Regional Water Quality Control Boards (RWQCB). The figure shows the lead regulatory agency depending on the type of facility and whether or not water quality is the environmental issue being addressed. In the next section, we describe the financial assurance requirements for solid waste facilities, hazardous waste facilities, and surface mines. Figure 4 summarizes these requirements.

|

Figure 3 Financial Assurances |

|||

|

Facility Type |

Number of |

Environmental Issue |

Lead Regulatory Agency |

|

Solid

waste |

282 |

All issues other |

California Integrated Waste Management Board. |

|

|

|

Water quality. |

Regional Water Quality Control Boards. |

|

Hazardous waste disposal, transfer, treatment, and storage facility |

255 |

All issues other |

Department of Toxic Substances Control. |

|

|

|

Water quality. |

Regional Water Quality Control Boards. |

|

Surface mines |

1,255 |

All issues other |

Department of Conservation (in conjunction with Surface Mining and Reclamation Board and local lead agencies [mainly counties]). |

|

|

|

Water quality. |

Regional Water Quality Control Boards. |

|

Figure 4 Basic Features of Financial Assurances |

|||

|

|

Facility Type |

||

|

Types of Financial Assurances |

Solid Waste |

Hazardous Waste |

Surface Mines |

|

Closure |

|

|

|

|

Assurance required for all facilities? |

Yes. |

Yes. |

Only mines affecting water quality and regulated by a Regional Water Quality Control Board (RWQCB). |

|

� Required up front? |

Yes. |

Yes. |

Yes. |

|

Amount based on estimated costs to complete closure for entire facility? |

Yes. |

Yes. |

Yes. |

|

� Can closure dates be estimated? |

Yes. |

Only for disposal sites; (not treatment, transfer, or storage). |

NA |

|

California Integrated Waste Management Board (CIWMB). |

Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC). |

RWQCBs. |

|

|

Post Closure |

|

|

|

|

� Assurances required for all facilities? |

Yes. |

Only for wastes placed in or on land. |

Only mines affecting water quality and regulated by RWQCB. |

|

� Required up front? |

Yes. |

Yes. |

Yes. |

|

� Amount based on 30-year cost to maintain facility? |

Yes. |

Yes. |

Based on costs to address water quality. |

|

� Required for 30 years? |

Yes. |

Yes, but can be renewed every ten years for another 30 years. |

NA |

|

� Administered by? |

CIWMB. |

DTSC. |

RWQCBs. |

|

Corrective Action |

|

|

|

|

� Assurance required for all facilities? |

�a |

�a |

�a |

|

Only for reasonably foreseeable releases into groundwater. |

Only after a release and remedy identified. |

Only for reasonably foreseeable releases into groundwater. |

|

|

� Amount based on estimated costs to mitigate? |

Yes. |

Yes. |

Yes. |

|

� Administered by? |

CIWMB. |

DTSC and RWQCBs. |

RWQCBs. |

|

Reclamation |

|

|

|

|

� Assurance required for all sites? |

NA |

NA |

Yes. |

|

� Required up front? |

NA |

NA |

Yes. |

|

� Amount based on estimated costs to reclaim land mined in prior year and upcoming year? |

NA |

NA |

Yes. |

|

� Administered by? |

NA |

NA |

Department of Conservation (in conjunction with Surface Mining and Reclamation board and local lead agencies). |

|

|

|||

|

a See answer below regarding whether assurance is required up front. |

|||

Three types of financial assurances are required for solid waste disposal facilities (landfills). The first type is the closure financial assurance, which covers the estimated costs associated with closing the facility. The second type is the postclosure maintenance financial assurance and includes the estimated costs for maintenance activities after the facility has been closed. The third type is the corrective action financial assurance and covers the costs associated with correcting the negative impacts from contamination at an operational facility (such as a release into groundwater).

Regulations for each type of financial assurance generally outline what costs should be included in the financial assurance cost estimate. Generally, these include costs for revegetation, gas monitoring and control, groundwater monitoring/remediation, drainage, and security. Financial assurances are updated annually for inflation and reviewed by CIWMB and the RWQCBs at least once every five years and adjusted for changes to the site. We discuss in turn each of these types of financial assurances below.

It should be noted that CIWMB administers and manages closure and postclosure financial assurances for solid waste facilities and receives input from the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) and the RWQCBs regarding water quality issues that should be addressed during closure and postclosure.

Closure. Once a facility stops receiving waste, it must fulfill certain closure requirements. These requirements are included in the closure plan that is submitted and approved upon application for a permit from CIWMB to operate a waste facility. Closure activities include installing the final landfill cover, ensuring the correct slope of the mound, and providing revegetation. Completing closure activities typically takes about two years. Closure dates are estimated based on the size of the facility and annual tonnage expected at the facility. The dollar amount of the closure financial assurance is based on the estimated costs to complete the closure activities. The financial assurance is required to be given up front at the time of the application for a permit to operate the facility.

Postclosure Maintenance. Postclosure maintenance begins once closure activities are completed and the site is determined by the state to be closed. Similar to the up-front requirement noted above, upon application to CIWMB to operate a solid waste disposal facility, the owner/operator is required by law to submit evidence of financial ability to provide for postclosure maintenance for 30 years (from the date of closure) to ensure the long-term protection of air, water, and land from the pollution due to the operations of the waste facility. Postclosure activities include maintenance of the grounds, monitoring of gas and water, the replacement of monitoring equipment, and record keeping to ensure continuing protection of human health and the environment. The dollar amount of the postclosure maintenance financial assurance is based on the estimated costs of these activities for 30 years.

Unlike the closure period, it is difficult to estimate the postclosure maintenance dates because it is impossible to know at the time of permitting the facility when the facility would no longer pose a threat following its closure. Statute requires the owner/operator to financially provide for 30 years of postclosure maintenance, but also indicates that the owner/operator is responsible for maintenance at the site until the site no longer poses a threat to the public or the environment, which could be for longer than 30 years. As discussed later in this report, CIWMB estimates that the state could face $1.8 billion in ongoing maintenance costs through mid-century as a result of expired financial assurances. Since state law does not require the owner/operator to demonstrate financial responsibility after the 30-year postclosure period, the state may end up stepping in to protect against a continuing threat to the public or the environment when the owner/operator does not have the financial resources to do so.

Corrective Action. In contrast to financial assurances for closure and postclosure, corrective action financial assurances cover activities when the facility is in operation, in closure, or in postclosure. For solid waste facilities, corrective action financial assurances are required up front by the RWQCBs only for reasonably foreseeable releases into groundwater. The dollar amount of the corrective action financial assurance is based on the cost of actions, such as pump installation, to mitigate such reasonably foreseeable releases.

There are also closure, postclosure maintenance, and corrective action financial assurances for hazardous waste facilities, which include disposal, treatment, transfer, and storage facilities. However, not all hazardous waste facilities are required to provide for all three types of financial assurances. The amount of financial assurances required for hazardous waste facilities is adjusted annually for inflation by DTSC.

Financial assurances for hazardous waste disposal facilities are reviewed at least every five years (during DTSC�s permit review) and financial assurances for all other hazardous waste facilities are reviewed at least every ten years upon the renewal of the permit. Separate from the review of financial assurances that takes place upon review or renewal of the permit, DTSC has also taken the initiative to review the cost estimates used in financial assurances on a periodic basis.

Closure. As with solid waste disposal facilities, once a hazardous waste facility ceases operation it must fulfill certain closure requirements. The dollar amount of closure financial assurances for hazardous waste facilities is estimated similarly to solid waste facilities and the assurances are also required upon application for a permit to operate a facility. However, closure dates cannot be estimated for hazardous waste treatment, transfer, or temporary storage facilities because, unlike landfills, these types of facilities do not have a finite capacity. This is because waste is not permanently stored at these types of facilities.

Postclosure Maintenance. For hazardous waste facilities, postclosure maintenance financial assurance is only required by DTSC for facilities where wastes were placed into or onto the land. For those hazardous waste facilities requiring a postclosure financial assurance, the postclosure maintenance activities are similar to those of solid waste facilities and are also required initially upon application to DTSC for the permit to operate.

In contrast to requirements for solid waste facilities where the 30-year postclosure financial assurance is required only once, DTSC can require prospectively a full 30 years of postclosure financial assurance each time the permit is renewed (at ten-year intervals) throughout the postclosure period, if this is needed based on facility-specific conditions. This is referred to as the �rolling 30-year� postclosure period.

Corrective Action. Corrective action financial assurances for releases into groundwater by hazardous waste facilities are only required by DTSC or the RWQCBs (depending on which is lead agency) once there has been a release and the solution to mitigate the release has been selected. This contrasts with solid waste facilities where the corrective action financial assurance is required up front for any reasonably foreseeable release into groundwater in the future. Therefore, there could be situations in which the owner/operator of a hazardous waste facility does not have the financial capability to mitigate the release and the state could face pressure to step in to finance the mitigation.

There is only one type of financial assurance required by DOC for surface mines: reclamation financial assurances. (Reclamation is the restoration of a site to a standard based on the ultimate use of the land once mining has ceased.) In addition, the RWQCBs require closure, postclosure, and corrective action financial assurances for surface mines that impact water quality and are regulated under board-issued waste discharge requirements.

Reclamation Required by DOC. Financial assurance requirements for surface mines differ from those for solid or hazardous waste facilities. To begin with, a financial assurance administered by DOC for a surface mine only covers the costs to reclaim the portion of the land scheduled to be mined in the following single year and the mined land not yet reclaimed from prior years. That is, the owner/operator does not have to demonstrate the financial capability to reclaim the entire surface mine as described in the reclamation plan for the site. (A reclamation plan under the Surface Mining and Reclamation Act [SMARA] is a written plan specifying how mined land will be cleaned up so as to minimize the environmental impacts of mining and render a site usable in the future for alternative purposes.) The DOC�s financial assurance guidelines generally outline what costs should be included in the calculation of the dollar amount of the financial assurance, such as costs for revegetation, road construction, and grading.

Local lead agencies (mainly counties) approve both reclamation plans and financial assurances while the department reviews these and provides comments to the local lead agencies. Recently, the California Supreme Court ruled that the department has standing to challenge the adequacy of reclamation plans and financial assurances for surface mining operations. Consequently, the department can take steps to ensure that reclamation plans and financial assurances are consistent with SMARA. Even though the state�s authority was clarified, it remains the responsibility of the local lead agency to annually inspect a surface mine and update the financial assurance cost determination.

Unlike the owner/operator of a solid or a hazardous waste facility, the owner/operator of a surface mine is responsible to reclaim the site to a specified condition regardless of the length of time it takes. Since the surface mine must be inspected every year, the department can annually update the dollar amount of the financial assurance to reflect the cost to reclaim the land that already has been disturbed as well as that which is to be disturbed in the next year.

Closure and Postclosure Maintenance Required by RWQCBs. Additionally, for surface mines regulated by the RWQCBs, a separate financial assurance for closure and postclosure monitoring is required to ensure that water quality issues are addressed when the mine ceases operation. Unlike closure and postclosure financial assurances administered by CIWMB and DTSC, closure and postclosure financial assurances administered by RWQCBs for surface mines are often combined into one financial instrument for administrative simplicity. The RWQCBs� financial assurance dollar amount includes the costs to reclaim the entire mine site, not just what is disturbed in the prior year and what is projected to be disturbed in the upcoming year. The dollar amount of this financial assurance is estimated based on costs for activities such as detoxifying heaps of mined material and grading for drainage.

Corrective Action Required by RWQCBs. The RWQCBs require corrective action financial assurances for all reasonably foreseeable pollution releases into groundwater. Just as the reclamation financial assurance is required up front before mining operations begin, corrective action financial assurances for foreseeable releases into groundwater are also required up front. The dollar amount of the corrective action financial assurance is based on the cost of actions, such as pump installation, to mitigate such reasonably foreseeable releases. Corrective action financial assurances required by the RWQCBs are the only corrective action financial assurances required of surface mines.

Figure 4 (see above) summarizes the financial assurance requirements for solid waste facilities, hazardous waste facilities, and surface mines.

As shown in Figure 5, the dollar amount of existing closure, postclosure, reclamation, and corrective action financial assurances totals about $5.7 billion. While the dollar amount is substantial, evidence (discussed below) suggests that it is insufficient to meet the state�s potential exposure by mid-century.

|

Figure 5 Dollar Amounts of

Existing Financial Assurances |

|||||

|

(In Millions) |

|||||

|

Facility Type |

Closure |

Postclosure |

Reclamation |

Corrective Action |

Total |

|

Solid waste disposal facilities |

$2,000.0 |

$2,200.0 |

� |

$100.0 |

$4,300.0 |

|

Hazardous waste facilities |

377.0 |

427.0 |

� |

105.0 |

909.0 |

|

Surface mines |

9.8a |

� |

$450.0 |

1.5b |

461.3 |

|

Grand Totals |

$2,386.8 |

$2,627.0 |

$450.0 |

$206.5 |

$5,670.3 |

|

|

|||||

|

a Includes postclosure financial assurance. |

|||||

|

b This amount covers both closure and corrective action. |

|||||

Types and Use by State Agencies. A financial assurance mechanism is the financial instrument that provides evidence to the state that the regulated business has the financial ability to restore public resources after they have been degraded by the business� operations. Statute specifies which mechanisms may be used by each of the state agencies, but also gives each state agency flexibility to allow other mechanisms if they are the equivalent to those specified in law. Additionally, California statute requires CIWMB and DTSC to allow those mechanisms specified in federal statute. Accordingly, all owners/operators choose from a range of financial assurance mechanisms.

The state agencies determine the financial assurance dollar amount based on the cost estimations described in the previous section, but do not prescribe which financial assurance mechanism the owner/operator must choose. Ultimately, the individual owner�s/operator�s financial condition, business situation, and personal choice drive the selection of the mechanism. Figure 6 describes the various types of financial assurance mechanisms and Figure 7 identifies which mechanisms are allowed by each state agency.

|

Figure 6 Financial Assurance Mechanisms |

|

|

Mechanism |

Definition |

|

Alternative mechanism |

Each

agency is allowed under statute to approve a financial assurance

mechanism not |

|

Corporate financial test |

An

owner/operator provides financial statements that demonstrate

adequate financial |

|

Corporate guarantee |

An

owner/operator demonstrates the ability to meet its obligations by

obtaining a |

|

Enterprise fund |

A trust fund of governmental entities supported by deposits of user fee revenues. |

|

Federal certification |

A commitment by a federal agency to complete the closure and postclosure activities at a site. |

|

Insurance policy |

A guarantee that funds shall be available from the insurer in an amount equal to the face value of the policy to meet the insured�s financial assurance requirements. |

|

Letter of credit |

A

guarantee by a bank that covers the owner's or operator's financial

assurance |

|

Local government test |

A

local government presents financial statements to demonstrate

adequate financial |

|

Local government |

A contract by which a local government promises to perform postclosure maintenance, compensate a third party for damages, or establish a fund to pay for such activities when it owns/operates a solid waste facility. |

|

Pledge of revenue |

A mechanism by which a local government promises to make specific, identified future revenue available to pay future postclosure maintenance costs. |

|

Surety bond |

A guarantee by a third party that closure and postclosure obligations will be fulfilled. Surety bonds are issued by surety companies (usually subsidiaries of insurance companies). |

|

Trust fund |

An account established by the owner or operator of a facility with a third party (trustee) for the benefit of the regulatory agency. The owner/operator deposits money into the fund over time. |

|

Figure 7 Financial Assurance

Mechanisms |

||||

|

Financial Assurance Mechanism |

CIWMBa |

SWRCBb |

DTSCc |

DOCd |

|

Alternative mechanism |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Corporate financial test |

Xe |

Xe |

Xe |

|

|

Corporate guarantee |

Xe |

Xe |

Xe |

|

|

Enterprise fund |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Federal certification |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Insurance policy |

Xe |

Xe |

Xe |

|

|

Letter of credit |

Xe |

Xe |

Xe |

X |

|

Local government test |

Xe |

Xe |

|

|

|

Local government guarantee |

Xe |

Xe |

|

|

|

Pledge of revenue |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

Surety bond |

Xe |

Xe |

Xe |

X |

|

Trust fund |

Xe |

Xe |

Xe |

X |

|

|

||||

|

a California Integrated Waste Management Board. |

||||

|

b State Water Resources Control Board. |

||||

|

c Department of Toxic Substances Control. |

||||

|

d Department of Conservation. |

||||

|

e Required by federal statutes. |

||||

Fiscal Risk to State Varies With Mechanisms. Financial assurance mechanisms vary in terms of the risk they pose to the state. Generally, those that are of higher risk to the state tend to be of lower up-front cost to the owner/operator. For example, the corporate financial test and corporate guarantee mechanisms are relatively risky from the state�s perspective. This is because the state could be faced with completely financing the costs to close and maintain the facility if the company or the affiliated company goes bankrupt. Yet, these mechanisms are relatively inexpensive for the owner/operator in terms of up-front cost. Additionally, these particular mechanisms require the state agency to carefully and closely review the periodic financial information of the company. Of the $804 million in closure and postclosure financial assurances currently required by DTSC, about 50 percent are secured through the corporate financial test or corporate guarantee.

In contrast, a trust fund is of relatively lower risk to the state because this assurance consists of actual monies deposited into the fund over time. The main risk is that the owner/operator will abandon or close the facility before the trust fund is fully funded to cover estimated obligations. This mechanism is relatively expensive for the owner/operator in comparison to other mechanisms because the owner/operator must set aside funds to the trust to cover its obligations.

As regards an insurance policy, the risk to the state varies largely depending on the willingness of the insurance company to cooperate with the state agency. For example, both CIWMB and DTSC have had experience with insurance companies not immediately providing payment, but expecting to negotiate a settlement with the state and the owner/operator for an amount less than the full assurance originally provided. Unlike a traditional insurance policy which insures for a discrete event which may or may not occur (such as a fire or car accident), insurance policies as financial assurances cover the estimated costs to complete activities over a long period of time that ultimately are certain to occur to some extent. Once the closure/postclosure activities commence, the insurance company makes annual payments to the owner/operator for these activities. Additionally, both CIWMB and DTSC, allow a form of self-insurance, referred to as captive insurance.

Our review finds that none of the financial assurance mechanisms provides a complete assurance to the state that the owner/operator will have the financial resources to complete the required environmental mitigation once the facility ceases operations. In the next section, we make recommendations to improve the use of these mechanisms to reduce the risk to the state of inheriting a substantial financial obligation due to the failure of the assurance mechanisms to perform as intended.

As previously mentioned, the state has long recognized its responsibility to mitigate the effects of natural and man-made emergencies and to protect the general health and safety of the people of California. However, the state has also generally recognized that those who adversely impact the state�s resources are required to mitigate their impacts. For this reason, the state requires financial assurances to guarantee the financial resources necessary to mitigate the effects of waste facilities and surface mines in order to protect the health and safety of the people of the state. However, we find that the dollar amount of existing financial assurances does not fully assure the financial resources necessary to mitigate the effects of these facilities, opening the state to potential financial risk. Furthermore, there is no dedicated funding source for unanticipated emergencies in connection with these facilities. Consequently, the General Fund has been and may be called upon in the future to fund these emergencies.

In this section we highlight issues for legislative consideration and make recommendations on how to improve financial assurance requirements. These recommendations are designed to ensure that the owners/operators of waste facilities and surface mines, rather than the general public, pay the costs associated with restoring and maintaining the site until it no longer poses a threat. Such an approach would be consistent with the polluter pays principle discussed earlier.

Our review finds that state agencies, when calculating the required dollar amount of financial assurances, frequently do not include all the costs necessary to prevent adverse impacts to the public and the environment. We discuss these gaps in the financial assurance cost calculations below.

Unanticipated Expenses Not Accounted For. Most financial assurance cost estimates do not include set asides for costs arising from unanticipated occurrences, such as severe storms resulting in stormwater runoff that impairs the environmental quality of the site. While it may be difficult to predict the weather, failure to account, in some way, for unanticipated costs means that the state may end up stepping in to pay for these costs when the situation poses an immediate threat to the public or the environment. This is because of the state�s overall responsibility to protect the general health and safety of the state�s population.

Replacement Costs Not Accounted For. Financial assurances typically do not include annualized costs to replace equipment used to maintain the site to control environmental risks that will wear out during the course of the postclosure maintenance period. For example, the electrical systems may need replacing after about 20 years-a time prior to when the responsibility on the owner/operator for postclosure maintenance may end. Or, equipment that is reasonably anticipated to outlast the postclosure maintenance period-such as concrete drainage channels, liner systems, and other durable items-may need replacement during the postclosure period, even though such equipment is excluded from postclosure cost estimates.

Gap in Addressing Water Quality Problems. While solid waste landfills and surface mines are required to provide a financial assurance up front (before they can operate), hazardous waste facilities are not. Rather, hazardous waste facilities are only required to provide such financial assurances after an actual release is identified and the remedy for the release has been selected. As a result, if a release into groundwater happens after hazardous waste operations have ceased, there is no guarantee that owners/operators have the financial resources to correct the release, even though they are legally required to clean up the site. (Costs could include such actions as pump installation and treatment.) Although DTSC argues that it is difficult to estimate these costs until a release into groundwater has actually occurred, we note that the RWQCBs already make these estimates for solid waste facilities and surface mines.

Limited Scope of Financial Assurances for Surface Mines. Finally, as discussed in the first section of this report, financial assurances for surface mines include only the costs associated with reclaiming the land that has been disturbed in prior years or is expected to be disturbed in the upcoming year. Under current law, the local lead agency must annually inspect a surface mine in order to update the financial assurance amount (based on prior year disturbance and estimated upcoming year disturbance) to be provided by the mine operator/owner.

However, if the local lead agency fails (for whatever reason) to complete an annual inspection, it is likely that the existing financial assurance has not been updated to include costs to reclaim all of the land that has been or is soon to be disturbed. For example, the financial assurance amount may be the amount to cover one acre of disturbance; however, if the lead agency fails to annually inspect the site and three acres of land have now been disturbed, the state has only secured funds to reclaim one acre of land. Largely because of outdated financial assurance amounts due to incomplete local inspections of active mines, the Office of Mine Reclamation at DOC estimates that the current surface mining-related financial assurances are not adequate by a factor of 10 to 100. Based on current financial assurance amounts, this equates to an exposure of $117 million to $1.2 billion.

LAO Recommendation: Broaden Scope of Costs Covered by Financial Assurances. To address the gaps in the costs covered by financial assurances, we recommend the enactment of legislation that requires that:

All financial assurances fully cover the costs for a reasonable schedule of equipment replacement during the course of the postclosure maintenance period.

Up-front corrective action financial assurances be provided by hazardous waste facilities to cover costs associated with reasonably foreseeable releases into groundwater.

Financial assurances for surface mines cover the total costs to reclaim the entire planned disturbance for the lifetime of the mine. (When an owner/operator submits its surface mine plan to the local lead agency for approval, the entire plan for the mine is presented. Consequently, the local lead agency could readily determine the total costs to reclaim the entire site.) This would bring surface mines in line with closure and postclosure financial assurance requirements for waste sites that similarly calculate the assurance based on the estimated closure/postclosure costs for the entire facility.

In addition to providing that new financial assurances required prospectively incorporate the above features, we also recommend that legislation require state agencies to incorporate such features when they review and update existing financial assurances.

We address the problem of the lack of accounting for unanticipated expenses in the financial assurance cost calculation later in this report. Specifically, we discuss alternative funding mechanisms to address cases when financial assurances fail to provide the funding.

In the previous section, we made recommendations to ensure that financial assurance cost estimates include all potential costs. In this section, we make recommendations regarding the use of the particular financial instruments that serve as financial assurance mechanisms in order to reduce the state�s risk during the postclosure period and to increase efficiency in the administration of financial assurances.

As mentioned earlier, about 50 percent of closure and postclosure financial assurances required by DTSC are secured through the corporate financial test or corporate financial guarantee. These mechanisms are relatively inexpensive for the owner/operator of the facility, but risky for the state. If the corporation or parent corporation suffers financial trouble, the state could face financing closure or postclosure activities at the sites (at least until it can potentially recover costs from other responsible parties).

LAO Recommendation: Eliminate Use of the Corporate Financial Test and Corporate Guarantee. Given the risk to the state, we recommend the enactment of legislation that prohibits private sector owners/operators from using the corporate financial test or corporate guarantee as financial assurance mechanisms when called upon to provide financial assurance in the future. Although existing state law requires CIWMB and DTSC to allow those financial assurance mechanisms specified in federal statute, including the corporate financial test/guarantee, there is no legal barrier to the state adopting financial assurance requirements that are more stringent than federal guidelines. Our recommended legislation would follow the lead of other states, including Massachusetts, Maryland, Montana, Nevada, and New York, that do not accept the corporate financial test/guarantee as a financial assurance mechanism for landfills and/or toxic waste sites, given the risk posed.

Both CIWMB and DTSC allow captive insurance. That is, if insurance is the chosen financial assurance mechanism, the insurance company could be owned (partially or fully) by the waste facility owner/operator (parent company). For this reason, the financial stability of the insurance company is completely dependent on the financial health of the parent company. Therefore, if the parent company declares bankruptcy, the insurance company would likely also declare bankruptcy, thus exposing the state to financial risk.

LAO Recommendation: Require Review of Financial Documents for Captive Insurance. Captive insurance is generally riskier to the state as a financial assurance mechanism relative to third party insurance. For this reason, we recommend the enactment of legislation requiring that, whenever captive insurance is the selected financial assurance mechanism, the state department requiring the assurance conduct an annual review that includes an evaluation of the financial health of the parent company as well as an independent assessment by a third party accountant.

At Cal-EPA, there are separate divisions within CIWMB, DTSC, SWRCB, and the RWQCBs that administer financial assurances for waste facilities. These divisions perform very similar activities, such as estimating closure and postclosure costs and reviewing financial assurance mechanisms. Although, CIWMB and DTSC oversee the financial assurance process for different types of waste facilities (solid waste versus hazardous waste), cost estimating for closure and postclosure and financial assurance mechanism review for these different types of waste facilities is generally the same. (As mentioned earlier, CIWMB already performs these functions on behalf of SWRCB and the RWQCBs.) It is inefficient for each of these agencies to perform similar activities.

LAO Recommendation: Consolidate Financial Assurance Functions into a Unit at Cal-EPA. We recommend the enactment of legislation transferring the financial assurance functions at CIWMB, DTSC, and SWRCB/RWQCBs into a new unit at the Office of the Secretary of Environmental Protection. We find that staff in each of these divisions is working on the same activities (albeit for different facilities) and that consolidating these functions will focus expertise and result in greater efficiencies and cost savings. There is precedent for establishing programmatic functions in Cal-EPA in the Office of the Secretary. For example, the Legislature established both an enforcement and a scientific peer review function in the Office of the Secretary to handle program issues that cut across a number of Cal-EPA departments.

In the previous sections, we made recommendations to improve financial assurances, including the use of financial instruments serving to provide the assurance. In this section, we make recommendations to establish a funding source in the event that the state has to cover some of the costs during the closure, postclosure, and mine reclamation periods. State costs could occur in four sets of circumstances, as discussed below.

The postclosure maintenance period has expired and the facility owner/operator is no longer responsible for maintaining the site under a financial assurance (referred to as post postclosure care).

The financial assurance mechanisms fail to provide the funds intended to be assured by them.

The financial resources of the owner/operator are inadequate to meet all costs incurred during the closure and postclosure periods.

A facility operated solely during a time period when financial assurances were not required.

Postclosure Maintenance Period Expires. As mentioned earlier, solid waste facilities are required to demonstrate their financial ability to provide for postclosure maintenance for 30 years after closure. Even though the owner/operator of solid waste facilities is generally legally responsible for maintaining a site after closure without a time limitation, financial resources to do so may not be available without a financial assurance in place. For this reason, CIWMB estimates that the state could face a $1.8 billion exposure for the ongoing maintenance of closed solid waste landfills by mid-century.

As a practical consequence, the time parameters put on these financial assurances may result in the state assuming substantial financial exposure once the �term� of a financial assurance expires. For example, CIWMB has estimated that in the next 20 years, the 30-year postclosure period will expire at a few landfills and the state will no longer have a financial assurance to ensure continued maintenance at these sites. If it is determined that any of these landfills with an expired financial assurance still poses a threat to the public or the environment, the state will face pressure to step in to at least partially finance maintenance activities. As discussed in the nearby box, CIWMB estimates that the potential state exposure for assuming responsibility for these maintenance activities could total $1.8 billion for the period up to mid-century.

How did the California Integrated Waste Management Board Calculate the $1.8 billion Potential State Exposure for Solid Waste Facilities?The California Integrated Waste Management Board (CIWMB) estimates that the state could face a $1.8 billion exposure for the ongoing maintenance of closed solid waste landfills by mid-century. The $1.8 billion in potential costs was projected to be all of the postclosure maintenance costs that would occur beginning on the 31st year after certification of closure of the landfill (public and private). At that point, it was assumed that any funds available from a 30-year postclosure financial assurance would be exhausted. For the 31st year (and beyond) of postclosure for each landfill, the board estimated the annual costs to continue maintenance at the site to be one-thirtieth of the total 30-year postclosure cost estimate. This estimate reflects the assumption that the postclosure maintenance costs will continue at the same average annual level as in the previous 30 years when the financial assurance was in effect. It does not reflect that some sites may require less monitoring and maintenance after 30 years of postclosure maintenance, while some landfills may require more. The $1.8 billion is arrived at by summing the annual maintenance costs assumed at each of the 279 landfills with expired financial assurances up to the middle of the century. While we have no way to independently verify CIWMB�s calculation, it appears to be the best available estimate of the state�s potential exposure at landfills. |

Financial Assurance Mechanism Fails. There can be situations in which the financial assurance mechanism itself fails. This can happen, when for example, an owner/operator declares bankruptcy and the corporate financial test was the selected financial assurance mechanism. In this situation, the owner/operator does not have the funds to cover closure and postclosure activities; therefore, the state may be on the hook to fund these activities (at least until it can pursue funding from other responsible parties) when the cessation of these activities would pose an immediate threat to the public or the environment.

Financial Assurance Amount Inadequate. As mentioned earlier, the financial assurance dollar amount may not be enough to cover unanticipated or updated costs incurred within the closure and postclosure periods. If the owner/operator has the financial resources to cover these costs, the financial assurance dollar amounts will be updated accordingly. However, if the owner/operator does not have the financial capacity to provide for these new costs, the state could be faced with funding these activities. For example, the state is currently pursuing funding from potentially responsible parties that sent hazardous waste to four hazardous waste landfills in the state because the owner of the landfills has declared bankruptcy and will not be able to cover the revised postclosure maintenance financial assurance. See the box below for information on this example.

A Failed Financial Assurance�-The IT Group Hazardous Waste LandfillsThere are four hazardous waste landfills in northern California owned by the IT Group. Each of these facilities is closed and has a postclosure permit issued by the Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC). These permits require ongoing postclosure operation, maintenance, and monitoring of the locations to address the public health and safety risk posed by the sites. The financial assurance that had been provided by the IT Group to cover the costs for postclosure for all four facilities is two prepaid insurance policies totaling $38.5 million that expire in 2029. Some funds have already been used for postclosure, leaving approximately $28 million for future postclosure activities. The IT Group declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy in January 2002. The DTSC and the Attorney General�s Office represented the state�s interests in the bankruptcy proceedings. As a result of the proceedings, DTSC entered into a consent order with the newly created IT Liquidating Trust that required the trust to provide additional financial assurance to cover the revised postclosure cost estimate of $53.5 million from 2004 through 2034. (This would cover the 30-year period required by law.) The shortfall in funding for the postclosure period is $24.5 million as a result of the $28 million remaining on the two insurance policies and the availability of $1 million in cash. In order to address this shortfall, the state has taken steps to recover funds from potentially responsible parties (parties who disposed hazardous waste at one of these sites). However, based on past experience, it is unlikely that the state would fully recover the costs it would assume by stepping in to ensure that the postclosure maintenance activities are carried out. Therefore, it is likely that the state would incur additional costs if needed to respond to an immediate health or safety threat to the public or the environment posed by these landfills. |

Facilities That Operated Prior to Financial Assurance Requirements. As noted in Figure 8, financial assurances have not always been required for waste facilities and surface mines. For example, there are approximately 1,450 pre-1988 solid waste disposal facilities for which a closure and postclosure financial assurance were not required. The CIWMB estimates that approximately 140 of these facilities have the potential threat of pollution or nuisance. While owners/operators of pre-1988 disposal sites are legally responsible for maintaining these sites to prevent adverse impacts to public health, safety, and the environment, the state or a public agency may end up assuming the maintenance costs when the responsible parties either cannot be found or do not have the resources to pay these costs.

|

Figure 8 Begin Dates of Financial Assurances Requirements |

||

|

Facility Type |

Environmental Issue |

Operational Aftera |

|

Solid waste disposal facilities |

All issues other than water quality |

1988 |

|

Solid waste disposal facilities |

Water quality |

1984 |

|

Hazardous waste facilities |

All issues other than water quality |

1984 |

|

Hazardous waste facilities |

Water quality |

1984 |

|

Surface mines |

All issues other than water quality |

1991 |

|

Surface mines |

Water quality |

1984 |

|

|

||

|

a Facilities that were operational after the year identified below have been required by the state to have financial assurances. |

||

The DOC estimates that there are about 40,000 abandoned mines throughout the state of which a majority operated and closed prior to financial assurance requirements. Of these, about 4,300 are estimated to present environmental hazards and 33,000 are estimated to present physical safety hazards. As with solid waste sites, the state or a public agency may end up assuming maintenance costs at hazardous waste sites and surface mines which pose a threat to the public or environment in cases where resources from responsible private parties are lacking.

LAO Recommendation: New Fee on Operational Facilities. To address the circumstances discussed above where financial assurances do not address all funding requirements, we recommend the enactment of legislation to establish a new annual tonnage fee to be assessed on all waste facilities and surface mines that are in operation. Fee revenues could be used (1) to continue maintenance activities at waste sites after the 30-year postclosure maintenance period if the site still poses a threat to the public or the environment, (2) to finance closure and postclosure activities when a financial assurance mechanism fails, (3) to finance unforeseeable costs (such as damages from earthquakes and extreme weather) in the event that the owner/operator does not have the financial resources to pay these costs, or (4) to finance urgent closure or postclosure activities at facilities that were not required to have financial assurances because they were operational and closed before financial assurances were required.

We find that it is appropriate for operational waste facilities and surface mines to pay this fee because there is a direct link between the activities carried on at these facilities and the long-term maintenance and cleanup of these sites that would be funded by the fee. While facilities paying the fee may also be required to provide financial assurances, it is important to note that the fee revenues would be used for state costs not met through the financial assurance.

It is also important to note that in contrast to facilities that are closed or are in postclosure, facilities that are still in operation generally have a stable revenue stream (such as, tonnage fees at landfills) that can be used to support the payment of the fee. Some may argue that having a rolling 30-year postclosure period is preferable to a new fee because it attempts to make the owner/operator responsible for the site until it no longer poses a threat. However, we find that, in practice, the rolling 30-year period does not adequately address future risk. This is because it is very difficult to assess whether or not a company will be financially solvent for up to 30 years into the future, especially since the particular facility will no longer be generating revenue. We think that levying a fee on operational facilities is far less risky to the state to ensure a stable funding source for these activities.

As regards the structure of the fee, it could be assessed on each ton of waste disposed, treated, stored, or transferred at a waste facility and each ton of material mined at a surface mine with revenues deposited into special funds at each of the respective state agencies.

The Legislature may consider exempting from this new fee publicly owned solid waste facilities which use a pledge of revenue as the financial assurance mechanism. Instead, these agencies could be required to be responsible for the maintenance of the site until it no longer poses a threat to the public or the environment (regardless of the time period, which could be for longer than 30 years). This is because it is very likely that local governments will be financially solvent many years in the future and also have the potential to raise new revenue, if necessary, to cover the costs of maintenance at these facilities. Additionally, such a long-term responsibility is in keeping with local governments� general responsibility to protect the health and safety of their citizens.

This new fee would be similar in design and purpose to the existing Underground Storage Tank Cleanup Fund fee, which is assessed on each gallon of petroleum that is stored in an underground storage tank. The revenue from this fee is deposited in an insurance-like trust fund and can be tapped by owners/operators of the storage tanks to pay for unexpected and catastrophic expenses associated with the cleanup of leaking petroleum underground storage tanks.

To provide some idea as to the level of the new fee for solid waste facilities, the CIWMB has recently estimated that in order for the state to build up a fund solely to provide for the maintenance of solid waste facilities when the 30-year postclosure period for a majority of the existing solid waste landfills has expired roughly 40 years from now, it would have to collect at least $18 million annually in new fees beginning today. This funding level is based on the $1.8 billion potential state exposure calculated by CIWMB. If such a fee were levied on all operational landfills, this would result in about a $0.45 per ton increase in the tonnage fee. (The average per ton fee in 2000-the most recent year available-was about $39.00. This amount consists of the landfill�s fee plus the state�s current tipping fee.)

LAO Recommendation: Eliminate the Rolling 30-Year Postclosure Period. We also recommend that the Legislature eliminate the rolling 30-year postclosure period for hazardous waste facilities. With the implementation of the new fee on operational facilities, hazardous waste facilities will cover the postclosure maintenance costs beyond the 30-year postclosure period, making the rolling 30-year postclosure period obsolete.

We find that the financial assurance requirements at various state agencies can be improved to ensure that waste facility and surface mine owners/operators are financially responsible for the pollution-related cleanup and maintenance of their facilities. We make recommendations to ensure that all financial assurances cover the costs for (1) a reasonable schedule of equipment replacement during the course of postclosure maintenance, (2) all reasonably foreseeable pollution releases into groundwater at hazardous waste facilities, and (3) the total costs to reclaim the entire planned disturbance of land at a surface mine.

Additionally, if the state acts now to set up a fee-based funding source to be used for post postclosure care and unforeseeable events at these facilities, a significant state cost pressure in the future may be averted.

Lastly, we find that certain financial assurance mechanisms, as currently structured, add to the state�s risk. We make recommendations to improve the use of these mechanisms to reduce the state�s risk of assuming a financial obligation due to the failure of the assurance mechanisms.

|

Acknowledgments This report was prepared by Michelle Baass, with the assistance of Jay Dickenson, and reviewed by Mark Newton. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814. |