February 2005

Proposition 98 is a complex formula for setting a minimum annual funding level for K-12 schools and community colleges. This primer is intended to assist the Legislature in understanding the basic "mechanics" of the proposition and showing how it has affected school spending since its passage in 1988. We also describe the Governor's proposed changes to Proposition 98 and discuss our concerns about how they would diminish legislative budget authority.

California voters enacted Proposition 98 in 1988 as an amendment to the State Constitution. This measure, which was later amended by Proposition 111, establishes a minimum annual funding level for K-14 schools (K-12 schools and community colleges). Proposition 98 funding constitutes over 70 percent of total K-12 funding and about two-thirds of total community college funding.

The Governor recently proposed major changes to the Proposition 98 funding guarantee for K-14 schools. To help the Legislature put the proposed changes into context, it is important to understand how the current guarantee mechanism works. This primer provides some basic information on Proposition 98 and how it has affected spending on K-14 education.

While the formulas get rather complicated at times, the goal of Proposition 98 is a relatively straightforward one. Generally, Proposition 98 provides K-14 schools with a guaranteed funding source that grows each year with the economy and the number of students. The guaranteed funding is provided through a combination of state General Fund and local property tax revenues.

Over the long run, the Proposition 98 calculation increases the prior-year's Proposition 98 funding level by the growth in K-12 attendance and growth in the economy (as measured by per capita personal income). The actual amount the state is required to spend on Proposition 98 each year, however, depends on specific calculations or "tests" (see Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Proposition 98 Basics |

|

|

|

|

|

� |

Over time, K-14 funding increases to account for growth in K-12 attendance and growth in the economy. |

|

� |

There Are Three Formulas (“Tests”) That Determine K-14 Funding. Which test depends on how the economy and General Fund revenues grow from year to year. |

|

|

Test 1—Share of General Fund. Provides 39 percent of General Fund revenues. This test has not been used since 1988‑89. |

|

|

Test 2—Growth in Per Capita Personal Income. Increases prior-year funding by growth in attendance and per capita personal income. Generally, this test is operative in years with normal to strong General Fund revenue growth. |

|

|

Test 3—Growth in General Fund Revenues. Increases prior-year funding by growth in attendance and per capita General Fund revenues. Generally, this test is operative when General Fund revenues fall or grow slowly. |

|

� |

Legislature Can Suspend Proposition 98. With a two-thirds vote, the Legislature can suspend the guarantee for one year and provide any level of K-14 funding. |

Currently, Proposition 98 spending (General Fund) is almost 45 percent of General Fund revenues. Test 1 of Proposition 98 requires the state to provide K-14 education at least 39 percent of General Fund tax revenues. However, this test was only operative in the first year of Proposition 98 and is not likely to be operative any time in the near future.

Proposition 98 funding usually grows with the economy (that is, Test 2 years). Proposition 98 funding, however, can grow more slowly under two different conditions:

Figure 2 shows the history of which test was operative. The figure shows that Test 2 has been the predominant test factor (12 of 18 years). This is not surprising given that the state's tax structure typically results in revenues growing faster than personal income. Test 3 years have tended to occur during state budget crises, when General Fund revenues have fallen year-to-year. So, Test 3 has reduced the pressure of Proposition 98 on the General Fund in years when the state was facing difficult budgets.

|

Figure 2 What Have Been the Operative Tests? |

|||

|

|

|

Growth Factors Per Capita |

|

|

Year |

Operative |

Personal |

General |

|

1998‑89 |

1 |

3.9% |

—a |

|

1989‑90 |

2 |

5.0 |

—a |

|

1990‑91 |

3 |

4.2 |

-4.0% |

|

1991‑92 |

2 |

4.1 |

8.0 |

|

1992‑93 |

3 |

-0.6 |

-4.4 |

|

1993‑94 |

3 |

2.7 |

-3.4 |

|

1994‑95 |

2 |

0.7 |

6.6 |

|

1995‑96 |

2 |

3.4 |

8.1 |

|

1996‑97 |

2 |

4.7 |

5.6 |

|

1997‑98 |

2 |

4.7 |

10.7 |

|

1998‑99 |

2 |

4.2 |

6.5 |

|

1999‑00 |

2 |

4.5 |

18.3 |

|

2000‑01 |

2 |

4.9 |

6.9 |

|

2001‑02 |

3 |

7.8 |

-18.6 |

|

2002‑03 |

2 |

-1.3 |

1.0 |

|

2003‑04 |

2 |

2.3 |

5.9 |

|

2004‑05 |

Suspended |

3.3 |

7.2 |

|

2005‑06b |

2 |

4.5 |

5.7 |

|

|

|||

|

a Test 3 was added to

Proposition 98 in 1990 by Proposition 111. Thus, per capita General

Fund revenues were not part of the |

|||

|

b Based on 2005‑06 Governor's Budget. |

|||

Recall that the intent of Proposition 98 is for K-14 funding to grow with attendance and the economy. When Test 3 years or suspension occurs, the state has provided less growth in K-14 funding than the growth in the economy. This funding gap is called the maintenance factor. Proposition 98 contains a mechanism to accelerate Proposition 98 spending in future years. This is called restoration of maintenance factor.

Figure 3 illustrates how the maintenance factor is created in one year and restored through accelerated growth in future years. In the figure, the state saves $2 billion in a suspension year, thereby creating a maintenance factor of the same amount. In this example, General Fund revenues grow faster than the economy in each of the next four years. As a result, the state provides an additional $500 million each year in accelerated growth or maintenance factor restoration. By year five, the state is back to a spending level that would have occurred absent the suspension. Figure 3 also shows that a suspension or Test 3 year results in state savings for several years. The state pays less than it otherwise would have until the maintenance factor is fully restored.

Figure 4 shows how the maintenance factor has fluctuated over time. Generally, once a maintenance factor is created, it carries forward for several years until stronger General Fund revenue growth allows for a reduction of this obligation. For example, as a result of several Test 3 years, the state created a maintenance factor in the early 1990s that grew to $2.2 billion by 1993-94. As General Fund revenues recovered in the mid-1990s, the state provided accelerated Proposition 98 growth and fully restored the maintenance factor by 1997-98. In recent years, the large outstanding maintenance factors are due to: (1) the dramatic revenue drop-off in 2001-02 (Test 3) and (2) the 2004-05 suspension.

Some have suggested that when the state creates a maintenance factor, it is borrowing from Proposition 98. This is not the case. When the state creates a maintenance factor, the state is saving the amount of the maintenance factor. And, while the General Fund savings are not permanent, the state never has to repay funding not provided to schools as a result of the maintenance factor.

For example, in 2004-05 under the Governor's proposed 2005-06 budget, the state saves $3.1 billion by its suspension of Proposition 98 in the current year. Under the existing Proposition 98 formulas, the state will over time provide accelerated growth to build the $3.1 billion back into the Proposition 98 base. However, until the entire $3.1 billion is restored, the state will continue to have annual General Fund savings.

As noted above, in good revenue years, the state makes accelerated payments to Proposition 98. As a result, the state must dedicate around 55 percent of new General Fund revenues to Proposition 98 in these situations.

Some people get confused by the 55 percent number, wrongly comparing it with Proposition 98's share of General Fund revenues—45 percent. The 45 percent figure is the average share of General Fund revenues devoted to Proposition 98 spending. The 55 percent figure only applies to additional General Fund revenues (year over year) and only in years when the state has an outstanding maintenance factor. The 55 percent figure is important to remember in those cases where General Fund revenues may be going up (due to updated projections, final collections, or proposed tax increases).

Yes. The state can provide funding above the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee in any fiscal year. However, since the additional funding becomes part of the Proposition 98 base for the next year's calculation, it becomes a permanent state obligation. Appropriations above the minimum (often referred to as "overappropriations") occurred annually for five years beginning in 1997-98, permanently raising the long-run Proposition 98 obligation level by almost $3.7 billion.

Within the guaranteed funding level, the Legislature has complete discretion on how it spends monies on schools. The Legislature can provide the funds for general purpose uses or for specific categorical programs. The state can also vary the mixture of funding that is used to support K-12 schools, community colleges, and child care.

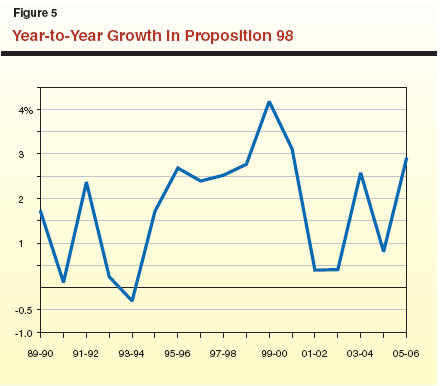

Not very well. Figure 5 shows the year-to-year growth in Proposition 98 spending. It shows that the guarantee has not provided K-14 education with a consistent and predictable growth in education funding. Part of the year-to-year volatility in funding is linked to the underlying volatility of the economy. But Proposition 98 funding is significantly more volatile than the economy. This is because of Proposition 98's reliance on the year-to-year changes in General Fund revenue. (In our recent report, Revenue Volatility in California, we discuss the history of the state's volatility in General Fund revenues and the factors causing this volatility.)

Yes, it has over the life of Proposition 98. However, as discussed below, education spending has experienced ups and downs.

Early 1990s Were Difficult Years for K-14 Education Funding. Proposition 98 had a difficult start. After Proposition 111 added Test 3 in 1990, three of the next four years were Test 3 years, providing K-14 resources that did not keep pace with growth in attendance and inflation. The maintenance factor grew to $2.2 billion (almost 10 percent of Proposition 98 funding at that time).

In the mid-1990s, as General Fund revenues recovered (Test 2 years), the state provided accelerated growth, fully restoring the $2.2 billion in maintenance factor by 1997-98. So from the start of Proposition 98 to 1997-98, funding grew in two distinct periods—slower than the economy through 1993-94, then faster than the economy between 1994-95 and 1997-98.

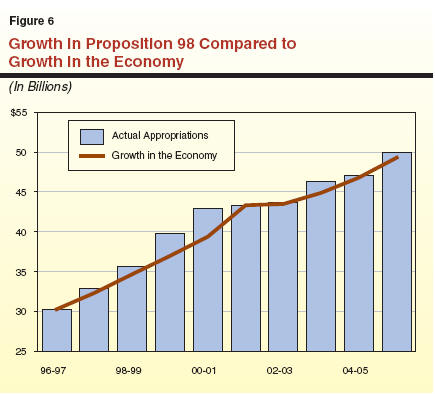

Spending Continues to Grow With Economy in Recent Years. On average, Proposition 98 funding has grown roughly as fast as the economy over the last decade. As Figure 6 shows, 2005-06 Proposition 98 spending is slightly higher than what the funding guarantee would have been in 2004-05 had the state funded education at the Test 2 level each year over the period. This overall trend, however, masks the facts that:

Usually, but not always. It depends on whether the economy and General Fund revenues grow faster than inflation. In some Test 3 years, the Proposition 98 calculation does not provide enough resources to fully fund growth and cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs). In most other years, the funding growth far exceeds growth and COLAs, leading to significant program expansions like the creation of the K-3 class size reduction program in 1996-97.

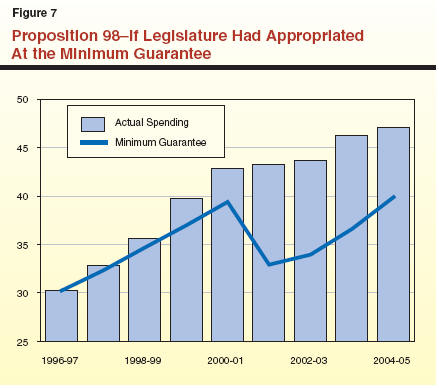

Figure 7 shows the level of funding the state would have provided for K-14 education if the state had spent at the minimum guarantee each year since 1996-97. In the current year, the guaranteed level would have been $7.2 billion less than is currently being provided. Much of the gap between actual spending and the minimum guarantee occurs in 2001-02, when General Fund revenues fell 17 percent.

Good question. Proposition 98 relies completely on year-to-year changes in General Fund revenues, and does not rely on the level of General Fund revenues. In 2001-02, General Fund revenues fell over 17 percent. Since 2001-02, the state's revenues have experienced moderate to strong year-to-year growth (2.6 percent in 2002-03, 7.5 percent in 2003-04, 8.7 percent in 2004-05, and 7.1 percent in 2005-06). Since Proposition 98 only looks at the year-to-year changes, the moderate to strong growth in revenues resulted in the recent years being Test 2 years requiring maintenance factor to be restored.

As the state budget begins to recover from a period of low General Fund revenues, Proposition 98 requires a large portion of the growth in General Fund revenues to be used for K-14 education. In both the mid-1990s and in recent years, as General Fund revenues recovered from a significant downturn, Proposition 98 required the state to accelerate the year-to-year growth in Proposition 98 funding to restore maintenance factor obligations. In these years, the education programs expanded substantially, while funding for other portions of the budget were constrained. For example, if the state had not suspended the guarantee in 2004-05, Proposition 98 would have required the state to provide an additional $3.1 billion above the budgeted level, which already funded growth and COLA and provided limited program expansion. This large augmentation of K-14 spending would have required other General Fund supported programs to be cut further. Alternatively, the state could raise tax revenues, but since roughly 55 percent of additional General Fund revenues would have been required to be spent on K-14 education, it is difficult to address the maintenance factor repayments with additional General Fund revenues.

Under the Governor's economic forecast, the state would be required to restore $375 million of maintenance factor in 2005-06 because General Fund revenues grow faster than personal income (General Fund revenues grow 6.2 percent per capita, and personal income per capita grows 4.5 percent). This funding is on top of the $2.5 billion in regular Proposition 98 growth (Test 2). The Proposition 98 funding formulas do not take into account the state's continuing structural imbalance between revenues and expenditures.

Between 2003-04 and the proposed 2005-06 budget, the General Fund cost of Proposition 98 has increased from $30.5 billion to $36.5 billion (a 20 percent increase). The reason for the rapid increase in General Fund costs is largely explained by two major local government agreements. The state transferred roughly $4.8 billion annually in local property tax revenues from school districts to local governments. These transfers were to compensate local governments for the vehicle license fee "swap" and the "triple flip" payment mechanism for the deficit-financing bond passed in March 2004. In both of these cases, local government exchanged one funding stream—state General Fund spending or the local share of sales tax revenues—for an equal dollar amount of school property taxes. The state, in turn, backfilled the property tax loss to schools with increased General Fund support under Proposition 98. These changes mean that K-14 education has become more reliant on the General Fund. The General Fund share of Proposition 98 has increased from 66 percent in 2003-04 to 73 percent in 2005-06.

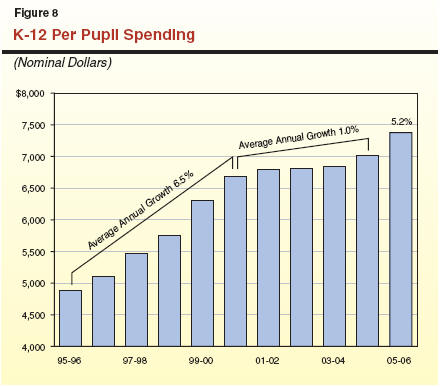

Figure 8 shows how K-12

Proposition 98 funding per pupil in actual dollars has

changed over the last decade. Actual per pupil

funding increased each year, averaging

4.6 percent annually over the last decade. Per pupil

spending has increased by almost $2,500 per pupil over the period (57 percent). These

figures however, do not take into account the

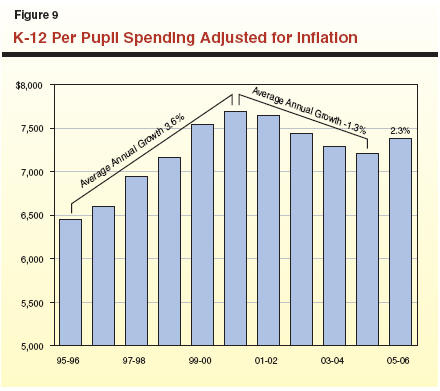

increases in costs that school districts face. Figure 9

shows K-12 per pupil funding adjusted for

inflation. After adjusting for inflation, per pupil

spending has grown around $930 per pupil over the

last decade (14 percent). This means that

schools have been able to expand programs by

around 14 percent over the last decade. Some of

these expansions included K-3 class size

reduction, large child care expansions, and new

school intervention programs. The figure shows

that funding growth has varied substantially over

the decade with three trends—(1) growth in

per pupil spending between 1995-96 and 2000-01 of $1,200 per pupil (3.6 percent annual

growth), (2) a decline of roughly $480 per pupil

between 2000-01 and 2004-05 (1.3 percent

decline annually), and (3) the Governor's

proposed $168 per pupil increase in 2005-06 (a change

of 2.3 percent). The state would need to

provide an additional $313 per pupil to return to

the high point in inflation-adjusted per pupil

spending

(2000-01). This would cost roughly an additional $1.9 billion.

As shown in Figure 6, reductions in recent years have generally offset funding gains that K-14 education made in the late 1990s when the state overappropriated the guarantee by a cumulative $3.7 billion. Some in the education community have suggested that education has been cut as much as $9.8 billion in cumulative reductions since 2000-01. We believe this estimate is technically flawed for several reasons discussed in Figure 10. The difficulty in determining how much has been cut really depends on the baseline used to determine the reduction. We believe that the decline in inflation-adjusted Proposition 98 funding per pupil for K-12 schools represents the magnitude of the reduction schools have experienced in recent years. We estimate that the state would need to provide an additional $1.9 billion above the proposed 2005-06 funding level to restore the real purchasing power of per pupil K-12 funding at its peak level in 2000-01.

|

Figure 10 Education Community’s

Estimate of |

|

|

|

|

|

� |

Mixing Expenditure Reductions and Revenue Reductions Double Counts Cuts ($3.5 Billion). Many of the K-14 expenditure reductions that the state made in recent years were required because the state provided $3.5 billion less in revenues over the period. The education community’s methodology counts both the reduction to revenues and the resulting reduction to expenditures caused by the lower spending level. |

|

� |

Does Not Offset Funding Reductions With Funding Augmentations ($500 Plus Million). Augmentations include High Priority Schools Program ($200 million), Special Education settlement ($125 million), equalization ($110 million), and nonstatutory growth and cost-of-living adjustments for numerous categorical programs. |

|

� |

Includes Rejection of Proposed Augmentation ($250 Million). The estimate includes as a reduction an augmentation that the Legislature chose not to fund ($250 million for K-12 equalization). |

|

� |

Continues to Count Reductions That Have Been Restored (Nearly $350 Million). The estimate includes reductions that the Legislature restored in 2004‑05 ($220 million for instructional materials and $129 million for deferred maintenance). |

As part of his proposed constitutional reforms to the state budget process, the Governor is proposing major changes to Proposition 98. The two biggest changes are:

The Governor proposes other changes to Proposition 98, which are summarized in the nearby box.

| Impact of Governor's Budget Reforms on Proposition 98

In addition to the proposed elimination of the suspension and Test 3 provisions, the Governor's proposals would do the following: Eliminate the "Ratchet Effect" for Proposition 98 Overappropriations. Currently, when the state provides funding above the minimum guarantee, those additional funds become part of the Proposition 98 base. This commits the state to higher K-14 spending levels for future years. The Governor would amend Proposition 98 to make appropriations above the minimum guarantee discretionary—that is, they would not become part of the base in determining the next year's funding level. Transition Existing Maintenance Factor to One-Time Payments ($3.7 Billion). The proposed elimination of the suspension and Test 3 provisions means that the state would not create any future maintenance factor. The Governor's proposal also would eliminate the existing obligation to make about $3.7 billion in maintenance factor restorations. Under current law, the state would build the $3.7 billion back in K-14 base spending over time as a result of good General Fund revenue years. The Governor instead would make one-time payments over a 15-year period that totaled $3.7 billion. The timing of these payments would be up to the discretion of the Legislature. If paid in annual increments, this would cost the state roughly $250 million annually for the next 15 years. Pay Off Prior-Year Proposition 98 Obligations Over a 15-Year Period ($1.3 Billion). According to the Department of Finance, the state owes almost $1.3 billion to meet minimum guarantee obligations for prior years. (These are one-time "settle up" obligations for selected fiscal years between 1995-96 through 2003-04.) The proposal would require the $1.3 billion to be paid in one-time payments averaging $83 million annually over a 15-year period. Current law would require annual payments of $150 million starting in 2006-07. Fully Reimburse Past State-Mandated Costs ($1.8 Billion). We estimate that the state owes around $1.8 billion to reimburse school districts for the costs of implementing state mandates in past years. The state would be required to use a portion of future Proposition 98 funding to pay for these mandates over the next 15 years. |

In our view, the elimination of the suspension and Test 3 provisions would greatly reduce legislative discretion during difficult budgetary times. For example, if the proposal had been in effect in 2001-02 when General Fund revenues fell by 17 percent, the state would have had to increase education spending by almost $4 billion more than what was budgeted. This, in turn, would have required comparable reductions to the rest of the budget—or significant revenue increases, limiting the Legislature's authority to set priorities.

In our view, they do not. In fact, they make things worse at the time that policymakers need the most tools—during difficult budget years. This is because they would lock in year-to-year spending in Proposition 98. As a result, the Governor's proposals would put Proposition 98 spending—almost one-half of the General Fund budget—on cruise control.

It is impossible to say. For school districts, there are three potential positives:

These potential positives, however, must be considered along with the following:

We concur with the Governor that there are problems with the Proposition 98 funding formula, particularly from a budgeting perspective. It involves complex calculations that few fully understand and generates funding results that are often unintuitive or—even worse—counterintuitive. While the administration's proposals would greatly simplify the funding formulas, it would do so at the expense of legislative budgetary authority and discretion. We believe the proposal, on balance, would add to the problems of autopilot spending and that the Legislature should consider other ways to improve Proposition 98 that do not involve such a serious diminution of legislative budget authority.

| Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by Rob Manwaring. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814. |