August 8, 2002

The recent withdrawals of health coverage by health maintenance organizations (HMOs) from rural areas have raised concerns about the availability of affordable health care in rural California. In this report, we discuss the reasons for this trend, and recommend a number of steps that we believe will create a more attractive health care marketplace for HMOs. In those rural areas where these steps are not enough to attract HMOs, we identify ways communities can develop their own health care systems based on the experience of one rural California county.

Chapter 208, Statutes of 2001 (AB 532, Cogdill) directed the Legislative Analyst's Office to study the operation of health care service plans, commonly known as HMOs, in rural California, report on the reasons these plans have discontinued their operations in rural areas, and recommend incentives for these plans to resume rural operations. Pursuant to Chapter 208, this report presents our findings and recommendations on these issues.

In preparing this report, we obtained information from a variety of sources:

We note that the findings and conclusions included in this report are those of the LAO, and do not necessarily represent the views of the groups or individuals cited above.

Traditionally, health insurance was commonly purchased through indemnity plans, not HMOs. Indemnity plans are a form of insurance in which the beneficiary pays the provider for medical services and then is subsequently reimbursed by the insurance company for covered expenses.

During the past 20 years, however, employers and government agencies discovered that they could reduce their health care costs by shifting employees from indemnity plans to HMOs. In an HMO, a designated physician acts as a primary care case manager, directly manages patient care, and serves as the main access point into the health care system.

The HMOs give health care providers a financial incentive to keep patients healthy and to manage utilization of health care services by prepaying providers a per-capita rate (an approach known as capitation). The providers assume financial risk under this arrangement because health care decisions they make may cost them more or less than the amount prepaid to them to provide necessary care. In addition, HMOs may make payments to providers based on measures of performance regarding quality, utilization, or other standards. The more risks that providers assume, the greater their potential profit or loss. In contrast, when a health plan pays a provider on a fee-for-service basis, the plan controls much of the decision-making authority.

The Legislature has become concerned about the increasing number of withdrawals of HMOs from rural counties. This concern is understandable because, in theory, HMOs could be beneficial to rural California. These plans could potentially provide residents of rural areas with greater access to affordable care, strengthen the rural health care delivery system, and allow for the provision of additional benefits to Medicare recipients that would not otherwise be available to them.

Access to Affordable Health Care. Historically, HMOs offer health care purchasers relatively comprehensive care at an affordable cost. The HMOs typically have lower out-of-pocket patient costs, broader benefits, and a greater emphasis on prevention and wellness than traditional indemnity plans.

A Stronger Health Care Delivery System. Managed care promotes the development of a local network of providers and could provide an opportunity for rural communities to strengthen their health care delivery system. The managed care system's emphasis on coordination of care across the delivery system may result in providers within that network working together more closely and effectively than might otherwise be the case. In addition, managed care's focus on clinical research, use of treatment protocols, and focus upon measurement and accountability for health outcomes has the potential to improve the quality of care within a rural network of providers.

Additional Benefits for Medicare Beneficiaries. One type of HMO that is found in some rural communities is "Medicare+Choice," an option offered to eligible seniors through the federal Medicare Program. These HMOs provide many seniors additional health care benefits, such as prescription drug coverage, that go beyond those available under traditional Medicare. Medicare beneficiaries who receive services through Medicare+Choice HMOs are often able to avoid having to pay the deductibles and copayments required under the traditional Medicare Program in return for staying within a fixed network of doctors and hospitals. Absent the availability of Medicare+Choice, health care costs, particularly for prescription drugs, could exceed the financial resources of some individuals on fixed incomes.

The first HMO in California, the Kaiser Health Plan, was initially established in the 1940s in California's urban areas. The HMO penetration into urban areas grew through the 1970s and 1980s. Eventually, the health plans began to target rural markets for expansion of HMOs, and additionally Medicare+Choice HMOs entered the rural health care marketplace.

By the late 1990s, HMO profits began to shrink, some plans experienced financial losses, and the highly competitive California health care marketplace began to consolidate into fewer competitors. The focus of HMOs shifted to retaining a hold on profitable markets and on withdrawing from unprofitable areas. As a result, between 1997 and 2002, the number of commercial HMOs operating in California dropped from 34 to 26, with most HMO enrollment concentrated in urban areas. More than three-quarters of the total statewide population covered by HMOs (approximately half of the estimated 35 million persons living in California) was enrolled in five health care plans operating within nine urban counties—Alameda, Contra Costa, Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, Sacramento, San Bernardino, San Diego, and Santa Clara.

The HMOs also began to selectively withdraw operations from rural areas that they found to be unprofitable. The HMO enrollment has declined 24 percent overall since 1997 in 30 predominately rural counties, affecting an estimated 5 million residents who live there. The drop in HMO enrollment has been more significant within certain rural counties. For example, Shasta County experienced a 78 percent reduction in HMO enrollment in that time period, from about 20,600 to 3,400 enrollees. The HMO enrollment in Del Norte County dropped 95 percent—from about 3,500 enrollees to only 164.

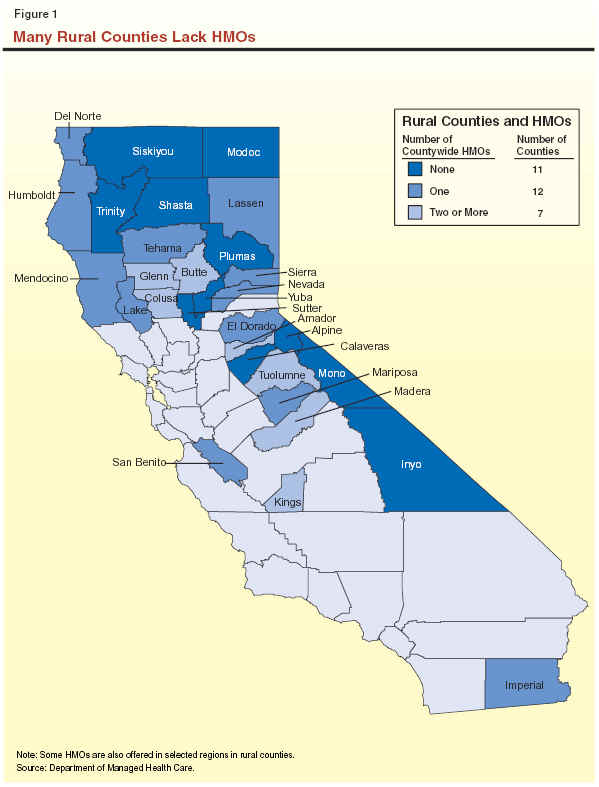

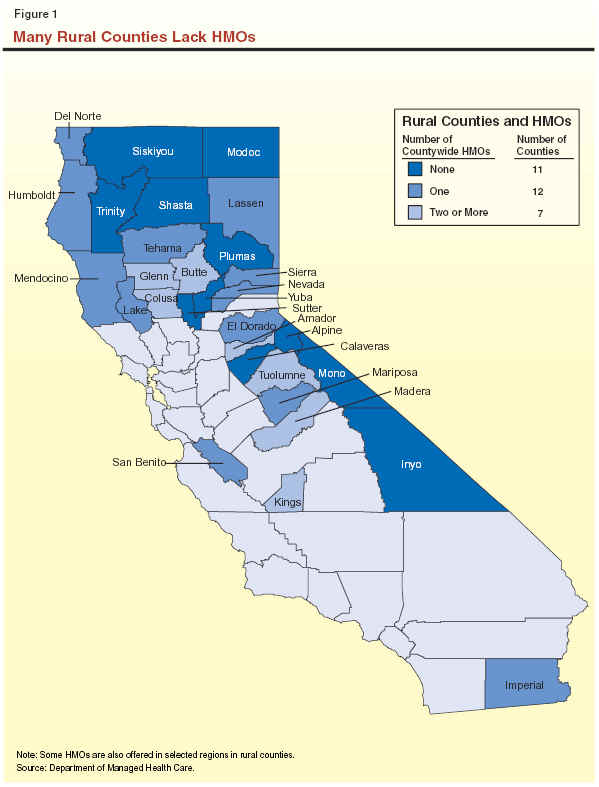

As the data reported by HMOs and shown in Figure 1 indicate, as of May 2002, about 37 percent of California's rural counties (11) no longer have any HMO that provides services to the county on a countywide basis. Four of these 11 counties have one HMO providing coverage within selected parts of the county. Data reported to state HMO regulators also indicate that 40 percent of rural counties (12) have only one HMO operating on a countywide basis. Seven of those counties have multiple HMO coverage only in selected areas.

For additional information on the number of HMOs operating in rural counties click here.

Medicare+Choice coverage has been significantly affected by the HMO pullout from rural communities. About 72 percent of rural counties no longer have a Medicare+Choice HMO. Of those rural counties with Medicare+Choice HMOs, one rural county (Madera) has two such HMOs, with the remainder having only one such health plan within their jurisdiction.

One study estimates that 84,000 Californians will lose Medicare+Choice coverage during 2002. The consequences of these changes for individual Medicare beneficiaries can be significant. In some cases, Medicare+Choice withdrawals have prompted some Medicare beneficiaries with significant medical needs to relocate from rural areas to communities where such coverage remains available.

Our analysis indicates that HMOs are withdrawing coverage from rural California largely because a combination of circumstances makes it difficult for them to operate profitably in such communities. These circumstances include a residential population that is relatively expensive to insure, the inherent difficulty of distributing the risks and costs of health coverage to a smaller population base, shortages of health care providers, expensive medical practices that increase costs, and concerns over reimbursement rates for care paid by health-care purchasers. The way the state regulates HMOs and operates its own health care assistance programs may be aggravating these problems. We discuss these specific factors in more detail below.

Rural residents, on average, have demographic characteristics that make them more expensive to insure and, therefore, less attractive to HMOs. As Figure 2 indicates, rural populations as a whole are older, poorer, more likely to be unemployed, and in poorer health than their urban counterparts. These factors often translate into a greater incidence of costly medical conditions that can drive up the cost of health coverage. For example, the number of expected cancer cases is greater in rural than in urban counties. In addition, not controlling for other factors, the data indicate that rural residents are about 25 percent more likely to die of cancer and about 16 percent more likely to die of heart disease than urban residents, which may be indicators of a less healthy rural population.

|

Figure 2 Selected Health Data for

the Rural California Populationa |

||

|

|

Rural |

Urban |

|

Population over age 65, 2000 |

14% |

11% |

|

Population who are Medi-Cal eligible |

18% |

15% |

|

Population below poverty, 1997 |

18% |

14% |

|

Unemployment, 2002 |

9.3% |

6.8% |

|

Number of deaths per 100,000 due to heart disease |

245 |

211 |

|

Number of deaths per 100,000 due to cancer |

214 |

171 |

|

Acute Care Hospital beds per 1,000 people |

3.1 |

2.9 |

|

Number of residents per doctor |

935 |

460 |

|

Number of community clinics per county |

2.8 |

20.4 |

|

|

||

|

a

Information

based on county wide averages. Unless otherwise indicated, data are for

1998 from the Department of Health Services. Other data sources include

www.fedstats.gov and the Department of Finance. |

||

As noted earlier, demographic factors result in greater utilization and costs for health care services in rural areas. However, these same rural areas often lack a sufficient population of healthy people who are less expensive to insure to help absorb the financial risk of serving higher-cost patients. A rural community may lack the population needed to make a commercial HMO financially viable there.

These problems are exacerbated by the significant proportion of individuals within rural communities—about 40 percent of the population—who are unlikely to enroll in HMO coverage. For example, in 1998, only 39,000 of the estimated 65,000 residents in rural Nevada, Lassen, Sierra, and Plumas Counties could have been enrolled in managed care. Most of the other 26,000 persons were unlikely to be enrolled in HMOs because they lacked the resources to obtain insurance coverage, chose not to have insurance, or were enrolled in fee-for-service Medi-Cal coverage.

Rural areas generally have a shortage of health care providers, including primary care physicians, family practitioners, and dentists, all of whom are in high demand by HMOs in urban areas. As Figure 2 indicates, the ratio of residents per doctor is much higher in California's rural communities (935 to 1) than in urban communities (460 to 1). One in three rural areas has a shortage of dentists, compared to one in ten urban areas. Rural counties also have far fewer community clinics, on average, than their urban counterparts. The overall shortage of these providers in rural areas poses a difficult challenge for HMOs attempting to fashion a comprehensive network of providers to serve their beneficiaries.

Research indicates that there are a number of reasons why many medical providers are reluctant to practice in rural California, including the view that rural group practices are financially unstable, the perceived lack of other primary care practitioners and specialists, inadequate medical facilities, limited access to new technology and procedures, and long distances to hospitals.

This shortage of medical professionals makes it difficult for HMOs to find providers who are willing to contract with them. Given limited local competition, many rural providers have little if any incentive to accept the lower reimbursements offered by HMOs in comparison to fee-for-service rates, or to assume the financial risk involved in capitation arrangements typically involved in a managed care setting.

Certain patterns and practices of medical care in rural communities appear to have made them a more expensive health care environment and thus a less attractive place for HMOs to provide coverage. One study has concluded that patterns of medical practice varied significantly between urban and rural areas in ways that had significant ramifications for the cost of health care. For example, certain types of surgeries were performed more frequently in rural areas than urban areas for individuals with the same types of medical conditions. The study suggested that these higher surgery rates could be driving up the cost of care in rural communities.

Health care plans have claimed that the low reimbursement rates being paid to them by two large purchasers of health care—specifically, Medicare+Choice and CalPERS—are prompting their withdrawal from rural communities.

The HMOs indicate that they have withdrawn from participation in Medicare+Choice because of what they consider to be low federal payment rates that inadequately compensate them for increases in the cost of prescription drugs that are often a key component of the coverage they provide.

Other health plans have linked their withdrawal from rural areas to what they contend is a CalPERS rate structure that creates a disincentive to provide coverage in rural communities. Under that rate system, CalPERS has paid each participating plan a uniform statewide negotiated rate in return for coverage. The plans assert that the CalPERS rate did not take into account the higher costs plans face in rural areas. As a result, they decided to discontinue coverage in areas found to be unprofitable.

Adequate data are not available to independently validate the assertion that Medicare+Choice and CalPERS rates are insufficient to offset the cost of care. We note, however, that the rates paid in urban and rural counties are generally comparable. Given the data suggesting that rural residents tend to be sicker than urban residents and have a higher cost of care, there is reason to believe that enrolling rural residents may not be as profitable to the HMOs as enrolling their urban counterparts.

The state may inadvertently be undercutting efforts to encourage HMO coverage in rural communities by operating its own major health assistance programs in rural areas on a fee-for-service basis instead of as managed-care programs. That is the case for the state's Medicaid program, known as Medi-Cal, which provides health care coverage to nearly 6 million Californians. While more than half of these beneficiaries are enrolled in managed-care plans, such enrollment is available only in urban counties. A 1993 strategic plan developed by the Department of Health Services (DHS) for the Medi-Cal managed care program stated the department's intention to limit managed care to urban counties, but provided no explanation for its decision to rule out expansion to rural areas.

The state has taken a similar approach in its assistance to the uninsured through the County Medical Services Program (CMSP). The CMSP, jointly supported by the state and counties, provides medical and dental care to approximately 51,000 low-income adults age 21 through 64 who are not eligible for Medi-Cal and who live in 34 rural and semi-rural counties. The CMSP enrollees receive services from Medi-Cal providers. Semi-rural counties where Medi-Cal managed care has been implemented, such as Sonoma, allow CMSP beneficiaries to enroll in such coverage. However, because Medi-Cal managed care does not operate in any rural county, most CMSP beneficiaries cannot enroll in managed care.

The exclusion of Medi-Cal and CMSP beneficiaries from managed care means that a significant population of health care consumers is not available for enrollment by HMOs. We estimate that the decision to exclude Medi-Cal managed care from rural counties has the effect of decreasing the potential enrollment of HMOs in such communities by about 230,000.

The Department of Managed Health Care (DMHC) licenses and regulates health care plans, such as HMOs. The department's mission is to work toward an accountable and viable health care system that promotes healthier Californians. However, our analysis suggests that the department has not done all it could, given the significant number of HMO withdrawals from rural areas, to preserve rural health care systems.

For example, our analysis indicates that, at least until recently, DMHC did not closely monitor which health plans were providing coverage in particular areas of the state. At the time we began to prepare this report, DMHC did not maintain a comprehensive and accurate list of the counties in which each health care plan operated. Absent such a list, there is no effective way to monitor HMO withdrawals on a statewide basis or to assess the cumulative impact of such withdrawals upon a particular county, including rural counties. (At our request, DMHC has since obtained this information from each health care plan and stated its intention to update this information annually.)

Chapter 208 directed our office to recommend incentives that would result in the resumption of HMO operations in rural communities. Accordingly, we recommend a series of steps below that we believe could help create a more attractive health care marketplace for HMOs and could help rural counties to develop their own health care systems in areas where HMOs may be unwilling or unable to operate. Our recommendations are summarized in Figure 3 and discussed in more detail below.

|

Figure 3 Restoring Managed Care to

Rural California |

|

|

|

·

Create an Attractive Marketplace. We recommend

strategies to encourage HMOs to return to rural areas by supporting the

improvement of the health care marketplace in rural areas through

workforce initiatives, improving infrastructure needed to deliver health

care, creation of purchasing alliances, and other actions. |

|

·

Foster Community Development of Health Care Systems.

We recommend the state assist local communities in their efforts to

establish locally controlled health care systems in those counties where

no HMOs or only one operate. This would enable rural communities to have

a system of managed care and obtain some of the benefits these systems

can provide. |

Our recommendations will not offer a quick fix to the problem of HMO withdrawal from rural areas. However, they do represent a practical and feasible approach to gradually improving the rural health care marketplace and creating new opportunities for managed care in a rural setting. Given the state's fiscal condition, it may not be feasible to immediately implement all of the approaches proposed in this report. However, we believe a number of these strategies could be implemented now at no or little state cost. Moreover, counties have some fiscal resources, such as county realignment funds, county tobacco settlement funds, and other discretionary funds that they might wish to contribute on a voluntary basis to implement some of the recommendations discussed below.

Alternative Approaches ConsideredAs we analyzed ways to address the pullout of HMOs from rural areas, we considered, but ultimately rejected, a number of frequently discussed alternatives. In interviews during the preparation of this report, the following proposals were often mentioned as offering a solution to the pullout of HMOs from rural counties. Below, we outline these alternative approaches and the reasons we do not recommend them at this time. Providing Direct Financial Incentives for HMOs. Based upon our analysis, we concluded that it would be difficult to establish direct financial incentives for HMOs (either in the form of tax relief or direct payments) of a magnitude that would result in a significant resumption of rural HMO operations. Given the deep-seated structural barriers that we believe underlie the pullout of HMOs from these communities, we concluded that such direct incentives would be ineffective, unworkable, and, given the state's serious fiscal problems, unaffordable at the present time. Any money-losing rural HMO would probably discontinue operations as soon as its losses outweighed any state subsidy. Mandating That HMOs Cover Rural Areas. We also considered but rejected the concept of exercising the state's regulatory authority to mandate that any health plan operating in the state provide coverage within rural communities. We concluded that this approach could have significant negative outcomes, including the likelihood of statewide increases in health care premiums to offset any losses that companies were forced to incur as a result of their rural operations. Moreover, this option could discourage some HMOs from operating in the state at all, ultimately making it a less competitive, and probably more costly, health care marketplace as a whole. Mandating That Providers Contract With HMOs. Yet another option we considered was to mandate that providers contract with HMOs so long as those HMOs agreed to pay them some minimum rate established by the state (such as the equivalent of Medi-Cal rates). In theory, this option could make it possible for some HMOs to return to the rural health care marketplace because additional providers would become available under this mechanism. We recommend against this option, however, because of our concern that such mandates could even further discourage providers from practicing in rural areas. Establishing More Flexible Access Rules for HMOs in Rural Areas. State regulations adopted by the DMHC require HMOs to provide reasonable access to all services—defined generally as providing access to primary care providers and a hospital within 30 minutes or 15 miles of all enrollees—for all of the persons they insure. Health plans contend that these regulations pose a barrier to operating in rural counties, and have proposed that state law be rewritten to relax the access standards. We considered such a change but would recommend against it. Our review of state law and regulations indicates that the law and DMHC regulations are already flexible enough to permit service in rural communities.

|

We recommend that the Legislature consider the approach of creating a more attractive health care marketplace to encourage HMOs to resume operations in rural counties. The specific recommendations are discussed in more detail below and are summarized in Figure 4. Our general approach is to attempt to reduce the barriers to rural coverage identified earlier in this report—in effect, to address the fundamental problems that our analysis indicates play a significant role in discouraging HMOs from operating in some rural communities.

|

Strategies

to Attract and Keep HMOs in Rural Areas |

|

|

|

·

Create and maintain a stable supply of health care

providers. |

|

·

Reform rural hospital operations. |

|

·

Allow rural areas to establish purchasing consortia. |

|

·

Enroll Medi-Cal and CMSP beneficiaries in managed care in

rural counties. |

|

·

Strengthen state review of HMO coverage withdrawals. |

As discussed earlier in this report, one reason why HMOs have exited from rural communities is a shortage of health care providers, and the resulting inability of HMOs to establish the contractual arrangements needed to implement a system of managed care. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature consider expanding state efforts to create and maintain a stable supply of medical professionals in rural areas. Below we discuss a number of steps the Legislature could take to advance this objective. They are presented generally in the order of their estimated potential fiscal impact, beginning with the lowest-cost options. However, depending upon the specific approach to its implementation, the cost to the state of any particular option could vary significantly. We recognize that given the state's current fiscal situation, several of these options would be difficult to implement at this time. Nevertheless, we present them here so that the Legislature may have a more complete picture of the alternative strategies available to it over the long term.

Encourage the Entry of Out-of-State Providers. The Legislature could consider easing licensure requirements for experienced primary care professionals from other states or foreign countries who agree to practice in a rural area for a designated length of time. These types of regulatory changes would involve little if any cost to the state. Specifically, the Legislature may wish to consider legislation to allow experienced providers licensed in other states, who agree to practice in a rural area, to be exempt from medical board examinations in California. (Chapter 507, Statutes of 2001 [AB 1428, Aanestad] already allows this for dentists.)

The Legislature could also support proposed federal legislation to expand an existing federal program to allow a larger number of immigration waivers for foreign physicians who commit to provide primary care in underserved areas for three years. This program does not waive licensure requirements for these foreign providers.

Recruit Students to the Health Professions. When the state can afford to do so, the Legislature may wish to consider implementing programs that encourage individuals from rural communities, who are more likely to want to live and practice medicine in a rural area once they obtain a degree, to pursue a health profession. The existing Health Professions Career Opportunity Program (HPCOP) provides grants to undergraduate colleges and universities for tutoring, counseling, and support services to students from underrepresented areas to help prepare them for admission to medical school. The Legislature may want to consider targeting some HPCOP assistance specifically to rural students. Additionally, the Legislature could support other assistance programs that introduce rural students to the health professions through specialized programs in high school and college, including health care internships.

Support Alternative Delivery Systems. The Legislature may want to consider proposals that could potentially reduce the workload of scarce physicians and pharmacists. For example, Chapter 310, Statutes of 2001 (AB 809, Salinas), authorizes the use of vending machines in specified clinics for the dispensing of certain types of prescription drugs. This innovative approach could remedy some of the problems that can result from a shortage of medical professionals.

One possibility for reducing physician workload could be to broaden the current authority of nurses who are working in a rural setting in which there is a shortage of physicians to write prescriptions for some medicines. Another vehicle for supporting the development of alternative delivery systems is the Rural Health Demonstration Project, which will end in July 2003 unless extended by statute. This pilot program, administered by the Managed Risk Medical Insurance Board, works to increase access to health care in rural areas for children enrolled in the Healthy Families Program. It does this by using various strategies, including creating alternative delivery systems such as mobile dental clinics and telemedicine services, and the extension of clinic hours in rural areas. Every dollar the state spends through this program draws down two dollars in support from the federal government.

Establish Rural Residency Programs. The Legislature could require that residency training programs for physicians in the state's public and private medical schools include the completion of at least some training in a rural area. Alternatively, the Legislature could establish a voluntary rural residency program that provides loan assistance or scholarships to residents who chose to serve a set period of residency in a rural area. Capital outlay grants and technical support could also be provided to help the state's medical schools develop rural facilities and programs.

Expand Loan Forgiveness Programs. The Legislature may want to consider creating a state-funded program to provide loan repayment for primary care providers who agree to practice in rural areas for a specified number of years. Recent legislation, Chapter 249, Statutes of 2001 (AB 668, Chan), commissioned a state study to be completed by June 2002 (our understanding is the report has been completed, but it has not yet been released) on the feasibility of establishing such a loan-forgiveness program for dentists.

Two pending Assembly bills propose scholarships and loan forgiveness programs for

health care providers who practice in underserved areas. One of the measures, AB 982

(Firebaugh), establishes loan repayment programs both

for physicians and dentists. Another pending bill,

AB 2935 (Strom-Martin), would facilitate pharmacists and pharmacies making a

voluntary contribution at the time they renew their

licenses, to a scholarship and loan repayment program for pharmacists.

Create a State Primary Provider Corps. One potential solution to an inadequate local health care workforce would be to create a state- and county-funded corps of providers who could be deployed to rural areas. Participating counties could voluntarily partner with the state by contracting for a designated number of state-hired providers at a predetermined cost. The significant costs of this approach to the state could be largely offset by county reimbursements, although some state subsidy of these arrangements would likely be necessary. Counties could use some of their realignment funds, their share of tobacco settlement funds, or other discretionary funds for this purpose. Providers could be encouraged to work for the corps by offering loan repayment programs or enhanced benefits packages.

Provide Tax Incentives. There may be tax-related incentives that could be considered provided that they can be structured in a cost efficient manner. For example, tax credits or income exclusions could be provided to medical professionals who decide to practice in a rural area after being licensed. These incentives could be limited to a specified number of years. If the Legislature decides to pursue such an approach, it should consider "targeting" such tax incentives as narrowly as possible and evaluating the cost-effectiveness of this type of strategy before making it permanent.

Adjust Medi-Cal Reimbursements. In February 2001, we issued a report (A More Rational Approach to Setting Medi-Cal Physician Rates) that presented research indicating that California's physician medical rates are low compared to rates paid by Medicare and other health care purchasers. While improving Medi-Cal reimbursement rates might not directly motivate HMOs to serve a rural area, our analysis suggests it might help to create and maintain a stable supply of medical providers in such areas.

The Legislature could require the state DHS to develop a more rational process for setting provider reimbursement rates for the Medi-Cal Program. We describe our proposal for such a process in more detail in our February 2001 report. When the state again has the financial resources necessary for this approach, it would then have the process in place to set provider rates at levels that would ensure reasonable access to services. The Legislature may also want to consider taking steps to ensure that reimbursement for telemedicine services—a key potential tool for providing medical services in remote rural areas—is adequate to ensure provider participation.

Rural hospitals face many serious challenges. They are required to maintain a broad range of services despite their smaller patient base, resulting in higher fixed costs per patient. Their limited financial resources also make it difficult for them to invest in new technology and update their facilities. According to the California Healthcare Association, in the last three years, one in five rural hospitals has closed or entered bankruptcy.

The Supplemental Report to the pending 2002-03 Budget Act directs the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development to report to the Legislature by February 2003 on the state of rural health care systems. The report is to include information regarding the financial health of rural hospitals and health systems, special challenges faced by rural hospitals and health systems, and possible regulatory, technical, or fiscal assistance that might improve rural health systems' fiscal and programmatic stability.

In addition to considering the recommendations resulting from this study, the Legislature should consider other reforms, such as encouraging the consolidation of rural hospital districts or establishing free-standing emergency departments that would maintain hospital emergency services without the expenses of a full-service hospital. In addition, the Legislature may want to consider measures such as AB 2271 (Aanestad) that would make it easier for rural hospitals to become designated critical access hospitals (CAH) eligible under federal law to receive supplemental payments through Medicare. (A hospital may qualify as a CAH if it has fewer than 15 beds, provides emergency services, and is at least 35 miles from another hospital.)

The Legislature may wish to consider legislation authorizing the formation of health care purchasing consortia within rural areas. As noted earlier, rural communities often lack the insurable population needed to sustain the operation of an HMO. One solution could be to allow the creation of consortia of health care purchasers that could, if necessary, cross rural county lines to establish a large enough population of insured people to sustain a managed-care system. For example, a consortium could be created to purchase coverage on behalf of employees of local businesses and government agencies within a geographic region that crosses county lines. Currently, there are other types of consortia that can be formed based on membership in professional associations. State law allows the members of a trade, industrial, or professional association to form so-called multiple employer welfare arrangements (MEWAs) to purchase health insurance. These groups are not insurance plans but are subject to regulation by the state Department of Insurance. Approximately 228,000 people are covered under the six MEWAs licensed in California. The Legislature may wish to consider enacting legislation that would allow rural communities to join together to form MEWAs.

The Legislature could increase the population available for enrollment in managed care plans and potentially attract HMOs to rural areas by expanding Medi-Cal managed care to rural counties and enrolling both Medi-Cal and CMSP beneficiaries in those plans. As mentioned previously, DHS has decided not to pursue establishing Medi-Cal managed care in rural areas.

One approach commonly used in rural areas in other states is primary care case management (PCCM). Several states, including Oregon, Washington, Arizona, and Minnesota have introduced Medicaid managed care in rural counties in this way. These PCCM initiatives have been a successful strategy for introducing rural areas to managed care and providing an entrée for the development of commercial HMOs. In California, they could become a path for restoring HMO coverage to rural areas.

Under the PCCM approach, a primary care provider is paid a small monthly case management fee to monitor and to approve the care of each enrolled Medicaid beneficiary. These fees are in addition to the regular fee-for-service reimbursements that the providers receive for the services they provide to their patients. In effect, providers are given financial incentives to better manage the health care costs of their patients, but without the traditional HMO capitation payment structure that some rural providers may find objectionable.

A PCCM-style plan currently provides services to Medi-Cal patients in Placer and Sonoma Counties. Sonoma County's plan began in the mid-1990s with 3,300 beneficiaries, and has successfully grown to cover 26,000 beneficiaries countywide. Most county providers participate in the PCCM, thus allowing good patient access to health services. The plan has implemented a number of managed care approaches to hold down health care costs, such as a phone service that assesses patients' health care needs and a disease management program for patients suffering from certain chronic conditions. The Sonoma PCCM is expected to convert to a more traditional type of managed care plan, including capitated payments to some providers.

Based on the experiences of Placer and Sonoma Counties, we estimate that moving counties to a PCCM-style managed care would initially add about $2 million in state costs to the Medi-Cal Program for case management fees. Given the level of savings the state now achieves through this program, these state costs would probably be largely offset by savings from reducing unnecessary services and providing preventative care to patients. The state could achieve significant net savings to the extent that the PCCMs later converted into HMO managed care plans.

We recommend that the Legislature consider establishing in state law a specific requirement that DMHC maintain a comprehensive database documenting the health care service plans operating within each California county. While the DMHC has already indicated its intentions to collect this information on a regular basis, we believe this data-collection requirement should be formalized. This would ensure that the department and other interested parties have the information necessary to monitor the extent of coverage on a county-by-county basis. We believe that the costs to DMHC to collect these data would be minor and absorbable since it recently collected the information within its existing resources.

We further recommend that DMHC make available to the public notices filed by health plans indicating their intention to withdraw health coverage from a given area. These notices would give communities facing the loss of HMO coverage early warning of pullouts and give them more time to mitigate the likely disruption of health services and begin development of alternative systems of care.

The expectation that a traditional managed care system will be available in every rural county within the state is probably unrealistic. Some counties, such as Alpine and Modoc, are so sparsely populated that managed care may never be able to operate effectively there. Even if the various actions we have outlined in this report to improve the rural health care marketplace were implemented, some rural counties may still lack the basic market conditions necessary to develop and sustain HMO health plans.

The establishment of a locally controlled health system may fulfill the needs of communities that are not yet ready, and may never be ready, for traditional HMO operation. Under this alternative to a traditional HMO, health care providers and other key local stakeholders enter into arrangements, generally under the auspices of a nonprofit agency, to provide and coordinate health care services and meet the other health care needs of the community.

We recommend that the Legislature consider steps to foster the development of locally controlled health systems in California's rural counties. Figure 5 summarizes several steps the state could take to assist rural communities in the development of such health care systems. These state efforts to encourage the development of such health systems would be coordinated through the Rural Health Policy Council, discussed later in this report.

|

Figure 5 Steps to Help Communities

Establish Health Systems |

|

|

|

·

Enact a statutory model for developing local health plans. |

|

·

Clarify antitrust laws in rural areas. |

|

·

Provide technical assistance to communities to establish

health systems. |

California's Siskiyou County provides an example of how a community was able to fashion an effective local approach to its health needs including many of the beneficial components of a traditional managed care system. (See the related discussion of Siskiyou County's experience.)

Arkansas has adopted a model statute outlining how to create a bridge between state government and local communities when developing locally controlled health systems. The California Legislature may wish to consider enacting a similar measure that would provide a roadmap for local communities in California interested in following a similar approach.

We believe a number of features of the Arkansas statute should be considered for incorporation into a California law. The local health care systems established in Arkansas are managed by nonprofit organizations administered by boards of directors comprised of local hospital representatives, physicians, other nonphysician and nonhospital providers, and members of the rural community.

These nonprofit entities are charged with the responsibility of establishing a rural health care network, or a combination of networks, in which hospital, medical, health education, and other health-related services work in a cooperative arrangement. Like managed care, the network emphasizes disease prevention and early diagnosis and treatment of medical problems. The nonprofit must collect data and report to the Legislature on the results of client member surveys and provide recommendations to improve and expand the program.

The Legislature may wish to consider legislation that would clarify antitrust regulations for providers who seek to develop new delivery systems in rural areas. This is because the scarcity of providers in rural areas means that most of them would have to collaborate in order to establish a successful locally managed care network. However, such a contractual arrangement might constitute a monopoly in violation of state antitrust laws.

Managed care experts indicate that it is not clear whether such collaborative arrangements would constitute an illegal monopoly under current state law or regulation. This lack of legal clarity was a barrier to a recent privately funded effort to establish provider networks in five rural communities with few providers. Accordingly, the Legislature may wish to clarify that state law permits these types of collaborative activities in certain circumstances. A number of other states have taken similar steps to ensure that such networks are immune from prosecution under antitrust law.

In our view, the withdrawal of HMOs from some rural communities provides a legitimate public policy justification for providing an exemption from antitrust laws for collaborative arrangements intended to implement locally controlled health initiatives.

Types of Assistance. The Legislature may wish to consider supporting programs that provide technical assistance for the development of locally controlled health systems to rural communities and providers that have had limited, if any, experience with managed care. Examples include facilitating the exchange of information on this subject among rural communities, providing technical assistance to such communities, and encouraging partnerships for this purpose between public and private stakeholders. The state could also provide on-site or video conferencing training seminars explaining how communities could develop their own network of health care providers. These training sessions could identify and share "best practices" that communities could use as a model, including technical assistance on the information technology needed to implement systems of managed care in a rural setting.

Other types of assistance may include helping nonprofit organizations that intend to develop such health plans to draft and negotiate contracts designed to link the participants into a provider network. Nonprofits may require advice about the types of computer systems and software needed to capture the data necessary for a managed health care system. Consumers also may need assistance about how to adjust to the new system for delivering health care.

Preconditions for Assistance. Before providing technical assistance, the state should ensure that a community seeking help has taken the steps necessary to ensure local support for such an effort. This support could be demonstrated through town-hall meetings or surveys conducted to consider the health care needs of residents. Representatives of local government, health care recipients, providers, and the community at large should be identified who would be willing to serve later on the local board that would govern the locally controlled health care plan.

Who Would Provide Assistance? The Rural Health Policy Council is a statutorily created panel composed of the various department directors and managers of agencies under the supervision of the state Health and Human Services Agency. The council has a small administrative support staff, whose current duties are now largely limited to awarding small capital grants, establishing an employment clearing house, and distributing a newsletter to rural constituents. The current role of the council could be expanded to include identifying and providing assistance to rural areas that are interested in establishing their own health care systems.

Costs and Funding of Assistance. The provision of such assistance, which could cost millions of dollars on a one-time basis if provided to rural communities across the state, could be limited due to the state's financial difficulties. However, the state cost could be minimal if the Legislature enacted legislation that encouraged relationships between HMOs and rural counties. For example, HMOs could receive a discount on the annual assessments they must pay to the state in exchange for the plans providing technical assistance for the establishment of community-based health plans.

Siskiyou County's Community Developed Health Care InitiativeThe Community Health Plan of the Siskiyous (CHPS) in Siskiyou County is a locally controlled health care plan that could become a model for similar ventures in California. The product of local community decision-making, this nonprofit organization has grown significantly since its creation in 1991. The CHPS now operates a network of over 500 health care providers throughout the region with over 3,000 enrollees. The CHPS began after Siskiyou community leaders convened a grassroots partnership of about 40 volunteers, including representatives from schools, consumer groups, businesses, senior citizens, local government, public health, and various health care professionals. Over several years, CHPS conducted a comprehensive assessment of community needs, leading to the development of a locally based health plan. The CHPS formed a health plan task force and recruited a part-time executive director to implement the proposal. Initial efforts focused on raising capital to support the health plan from area residents and organizations, including local physicians and the county's two private, nonprofit hospitals. After extensive deliberations over its legal form, governance, philosophy, and other issues, the task force named an interim board of directors and formally incorporated CHPS in 1994. The majority of the board of directors consists of laypersons who are not otherwise involved in providing health care services. The CHPS subsequently entered contracts providing fee-for-service reimbursement for most local physicians and the two local hospitals. By the end of 1995, CHPS had convinced its first local employer to begin using the CHPS network to provide health services for its self-insured benefit plan. The nonprofit expanded its operations during the next five years, retained a management services company to provide leadership stability after twice changing executive directors, and raised nearly $5 million to build a new facility to replace the older of the two local hospitals. The plan also expanded its operations to provide claims administration and medical management services, as well as coverage outside Siskiyou County. As a result of these accomplishments, CHPS' revenue has grown dramatically since 1999. The CHPS' board has decided to convert the organization into a "membership" corporation and to create a charitable 501(c)(3) organization to ensure that CHPS' resources remain focused on benefiting the community. The health plan is developing a product that would provide coverage to small employers and their employees. The CHPS representatives believe that theirs is an effective model for other rural health plans because it directs back into the local economy dollars that would otherwise be spent outside the local community. In their view, CHPS holds down health care costs by effectively managing care, while expanding access to health care by making services and coverage more affordable and freeing up resources to subsidize care for the uninsured. The plan attributes its success to operating locally, which enables it to understand and respond quickly to changes in the community's needs. The plan also attributes its success to not expanding too rapidly. For example, CHPS has been working on its small group insurance product for three years.

|

After rapidly expanding in the early and mid 1990s, a decline in profits later in the decade prompted California HMOs to consolidate their operations and, eventually, to withdraw from less profitable rural areas.

Our analysis indicates that the factors contributing to the pullout of HMOs from rural areas include demographics that on average make rural Californians more expensive to cover, a population size insufficient to distribute the financial risk of coverage, a shortage of health care providers, certain medical practices patterns, and low reimbursement rates from major health care purchasers. State regulatory efforts did not prevent the pullout of the HMOs, and the state may have actually inadvertently contributed to the problem through its own HMO regulations and by not establishing managed care within its own programs in many rural counties.

If it wishes to overcome these barriers and bring about a reentry of managed care to rural communities, we recommend that the Legislature focus on the fundamental problems that now make rural areas an unattractive marketplace for HMOs. Because some communities may never be able to attract commercial HMO operations, we also propose that the state help rural counties to establish locally controlled health care systems. Several of the recommendations we have offered in this report would require additional resources from the state General Fund. Given the state's fiscal situation, we recognize that it may not be possible to implement some of these actions at this time. However, we note that a number of our proposals could be implemented incrementally to minimize the initial commitment of state funding, and that the state could move forward with other options with little or no state funding.

| Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by , Farra Bracht and Lisa Folberg, under the supervision of Daniel C. Carson. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814. |